A predisposed factor to political party affiliation refers to the underlying influences that shape an individual's likelihood of aligning with a particular political party. These factors often stem from a combination of personal, social, and environmental elements, such as family upbringing, socioeconomic status, education, cultural values, and geographic location. For instance, individuals raised in households with strong political traditions are more likely to adopt similar affiliations, while socioeconomic conditions can drive support for parties perceived to address specific economic concerns. Additionally, regional or demographic identities, such as rural versus urban living, can predispose individuals to certain political ideologies. Understanding these predisposed factors is crucial for analyzing voter behavior and the broader dynamics of political polarization.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Socioeconomic Status: Income, education, and occupation often influence political party affiliation and voting behavior

- Cultural Identity: Ethnicity, religion, and regional heritage shape political preferences and party alignment

- Generational Differences: Age groups tend to lean toward specific parties based on historical and social contexts

- Geographic Location: Urban, suburban, or rural living environments correlate with distinct political party support

- Family Influence: Parental political beliefs and household discussions significantly impact individual party predispositions

Socioeconomic Status: Income, education, and occupation often influence political party affiliation and voting behavior

Socioeconomic status (SES) acts as a silent architect of political landscapes, shaping party affiliations and voting behaviors through the interlocking forces of income, education, and occupation. Consider income: higher earners often align with conservative parties advocating for lower taxes and deregulation, while lower-income voters tend to support progressive platforms emphasizing social welfare and wealth redistribution. This isn’t deterministic—exceptions abound—but the trend is statistically robust across democracies. For instance, in the U.S., households earning over $100,000 annually are 15% more likely to vote Republican, whereas those earning under $30,000 lean Democratic by a 20% margin.

Education introduces a layer of complexity, often moderating the raw impact of income. Highly educated individuals, regardless of income bracket, are more likely to prioritize issues like climate change, healthcare reform, and civil liberties. This explains why college-educated voters in suburban areas have shifted toward progressive parties in recent decades, even when their earnings align with conservative fiscal policies. Conversely, less-educated voters, particularly in blue-collar occupations, often gravitate toward populist or nationalist parties that promise job security and cultural preservation. The Brexit vote in the U.K. exemplifies this: areas with lower educational attainment overwhelmingly supported leaving the EU, driven by concerns over immigration and economic displacement.

Occupation further refines these patterns, acting as a bridge between income and education. Professionals in tech, academia, or creative industries—fields requiring higher education—tend to vote for parties promoting innovation, diversity, and global cooperation. In contrast, workers in manufacturing, agriculture, or service industries often favor parties that prioritize domestic jobs and traditional values. This occupational divide is stark in countries like France, where urban professionals back centrist or left-leaning parties, while rural and industrial workers support right-wing populists like Marine Le Pen.

To navigate these dynamics, consider three practical takeaways. First, recognize that SES isn’t a monolith—its components interact in nuanced ways. A low-income individual with a college degree might defy income-based predictions by voting for a party focused on student debt relief. Second, contextualize SES within broader systems. In countries with robust social safety nets, lower-income voters may feel less urgency to support radical change, whereas in nations with high inequality, they’re more likely to back transformative policies. Finally, acknowledge the limits of SES as a predictor. While it’s a powerful predisposing factor, personal values, regional culture, and short-term events (e.g., economic crises) can override its influence. Understanding SES as a framework, not a formula, sharpens our ability to interpret political trends and engage in informed discourse.

Taxing the Wealthy: Which Political Party Advocates for Higher Taxes?

You may want to see also

Cultural Identity: Ethnicity, religion, and regional heritage shape political preferences and party alignment

Cultural identity, encompassing ethnicity, religion, and regional heritage, profoundly shapes political preferences and party alignment. For instance, in the United States, African American voters have historically aligned with the Democratic Party due to its stance on civil rights and social justice, while Hispanic voters, though diverse, often lean Democratic based on immigration policies. Conversely, white evangelical Christians predominantly support the Republican Party, driven by shared values on issues like abortion and religious freedom. These patterns illustrate how cultural identity acts as a predisposing factor, guiding individuals toward parties that resonate with their core beliefs and experiences.

To understand this dynamic, consider the role of shared narratives and historical grievances. Ethnic groups often rally behind parties that address their specific struggles or celebrate their heritage. In India, regional parties like the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) in Tamil Nadu thrive by advocating for Tamil cultural pride and linguistic rights, contrasting with the broader nationalistic agenda of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Similarly, in Europe, parties like the Scottish National Party (SNP) leverage regional identity to push for autonomy or independence, attracting voters who prioritize local heritage over national unity. This demonstrates how cultural identity can override other factors, such as socioeconomic status, in political decision-making.

Religion further complicates this landscape by intertwining spiritual beliefs with political ideologies. In Israel, ultra-Orthodox Jewish parties like Shas and United Torah Judaism consistently advocate for policies favoring religious communities, such as exemptions from military service and increased funding for religious institutions. Meanwhile, in Muslim-majority countries like Indonesia, parties like the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) blend Islamic principles with populist appeals, attracting voters who seek governance aligned with their faith. These examples highlight how religious identity often dictates party alignment, as individuals seek representation that mirrors their spiritual and moral frameworks.

Regional heritage also plays a pivotal role, particularly in geographically diverse nations. In Canada, Quebec’s distinct French-speaking identity has fostered support for the Bloc Québécois, a party dedicated to promoting Quebecois interests and sovereignty. Similarly, in Belgium, Flemish and Walloon identities have given rise to parties like the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA) and the Socialist Party (PS), respectively, each catering to the cultural and linguistic priorities of their regions. These cases underscore how regional heritage can fragment national politics, as voters prioritize local identity over broader national agendas.

Practical takeaways for understanding this phenomenon include recognizing the importance of cultural narratives in political messaging. Parties that successfully frame their platforms around the values and histories of specific cultural groups are more likely to secure their loyalty. For instance, campaigns targeting Latino voters in the U.S. often emphasize family, community, and economic opportunity—themes deeply rooted in Hispanic cultural identity. Additionally, policymakers and analysts must avoid oversimplifying cultural identities, as they are multifaceted and can intersect with other factors like class and education. By acknowledging the complexity of cultural identity, stakeholders can better predict and engage with political preferences shaped by ethnicity, religion, and regional heritage.

Which Political Party Opposes Music Education in Schools?

You may want to see also

Generational Differences: Age groups tend to lean toward specific parties based on historical and social contexts

Age is more than a number when it comes to political affiliation. Each generation carries the imprint of the historical and social events that shaped their formative years, influencing their values, beliefs, and ultimately, their political leanings. This phenomenon, known as generational imprinting, creates distinct political profiles for different age groups.

For instance, consider the Silent Generation (born 1928-1945), who came of age during World War II and the Cold War. This era, marked by economic hardship, global conflict, and the threat of nuclear annihilation, fostered a strong sense of patriotism, traditionalism, and loyalty to established institutions. Consequently, this generation tends to lean conservative, favoring smaller government, strong national defense, and traditional social values.

Contrast this with Millennials (born 1981-1996), who entered adulthood during the 9/11 attacks, the Great Recession, and the rise of social media. These events instilled a sense of global interconnectedness, economic insecurity, and a desire for social justice. Millennials are more likely to support progressive policies like universal healthcare, climate change action, and LGBTQ+ rights. They are also more skeptical of traditional institutions and more open to alternative political movements.

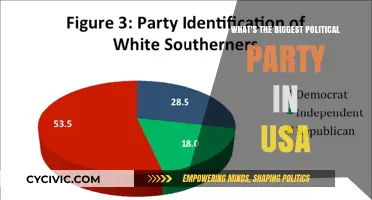

This generational divide is not merely theoretical. Data consistently shows a clear correlation between age and party affiliation. In the United States, older voters tend to favor the Republican Party, while younger voters lean towards the Democratic Party. This trend is not unique to the US; similar patterns can be observed in many democracies around the world.

Understanding these generational differences is crucial for political parties seeking to connect with voters. Tailoring messages and policies to resonate with the specific experiences and values of each age group can be a powerful strategy for building support. For example, a party targeting Millennials might emphasize student loan forgiveness and climate change initiatives, while a party targeting Baby Boomers might focus on Social Security and Medicare.

By recognizing the profound impact of historical and social context on political beliefs, we can better understand the complex landscape of political affiliation and work towards a more inclusive and representative political system.

Understanding Political Asylum: Rights, Process, and Global Implications Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Geographic Location: Urban, suburban, or rural living environments correlate with distinct political party support

Geographic location significantly shapes political affiliations, with urban, suburban, and rural areas often aligning with distinct party preferences. Urban centers, characterized by high population density and diverse demographics, tend to lean toward progressive or liberal parties. This correlation stems from the concentration of issues like public transportation, affordable housing, and social equity, which resonate with platforms advocating for government intervention and inclusive policies. For instance, cities like New York and San Francisco consistently support Democratic candidates due to their focus on urban development and social justice.

Suburban areas, on the other hand, often exhibit a more moderate political stance, reflecting a blend of urban and rural priorities. Residents in these zones frequently prioritize education, public safety, and economic stability, aligning with centrist or slightly conservative policies. The suburban shift toward the Democratic Party in recent U.S. elections, such as in 2020, highlights how changing demographics and concerns about healthcare and taxation can influence political leanings. Suburban voters are often swayed by candidates who address their specific needs without veering too far left or right.

Rural environments typically favor conservative parties, driven by values tied to self-reliance, traditionalism, and skepticism of federal overreach. Agricultural policies, gun rights, and religious freedoms dominate rural political discourse, aligning closely with Republican platforms in the U.S. or conservative parties in other countries. For example, states like Wyoming and Montana consistently vote Republican due to their rural populations' emphasis on local control and resource-based economies. This alignment is further reinforced by the perception that liberal policies disproportionately benefit urban areas.

Understanding these geographic predispositions requires examining socioeconomic factors. Urban residents often rely on public services, fostering support for expansive government programs, while rural dwellers may view such programs as intrusive. Suburban voters, situated between these extremes, often prioritize pragmatic solutions over ideological purity. Policymakers and campaigns can leverage this knowledge by tailoring messages to address the unique concerns of each environment, such as emphasizing infrastructure in urban areas or rural healthcare access.

Practical takeaways include recognizing that geographic location is not deterministic but a strong indicator of political leanings. Campaigns should avoid one-size-fits-all strategies, instead focusing on localized issues. For instance, a candidate targeting urban voters might highlight public transit expansion, while one appealing to rural constituents could emphasize agricultural subsidies. By acknowledging these geographic predispositions, political actors can build more effective and resonant campaigns that address the specific needs and values of their target audiences.

Washington's Warning: The Founding Fathers and the Peril of Partisanship

You may want to see also

Family Influence: Parental political beliefs and household discussions significantly impact individual party predispositions

The political leanings of parents often serve as a child’s first exposure to ideological frameworks. Studies show that 60% of individuals whose parents actively discuss politics at home align with their parental party by age 18. This isn’t merely about inheritance; it’s about immersion. Children in households where political discourse is frequent—whether at dinner tables or during news broadcasts—absorb not just opinions but the underlying values and reasoning behind them. For instance, a family that consistently critiques government overreach may foster libertarian tendencies in their offspring, while one emphasizing social welfare programs might nurture progressive inclinations. The frequency and tone of these discussions act as a political primer, shaping how young minds interpret societal issues.

Consider the mechanics of this influence: parental beliefs act as a cognitive shortcut for children navigating complex political landscapes. When a parent labels a policy as "fair" or "unjust," the child internalizes this judgment as a heuristic for future decisions. This is particularly potent during adolescence, a period when abstract reasoning develops but critical thinking is still maturing. A 2018 study found that teens who engage in weekly political conversations with parents are 40% more likely to register to vote in their first eligible election, demonstrating how early exposure translates into lifelong civic behavior. However, this dynamic isn’t without risk; overly dogmatic household environments can stifle independent thought, turning predisposition into prejudice.

To mitigate this, parents should adopt a Socratic approach, encouraging questions over declarations. For example, instead of stating, "This policy is wrong," ask, "What do you think are its pros and cons?" This fosters analytical thinking rather than blind allegiance. Additionally, exposing children to diverse viewpoints—via media, community events, or cross-partisan discussions—can balance familial bias. Schools and educators play a role here too, by creating safe spaces for students to explore ideologies beyond their home environment. The goal isn’t to erase family influence but to ensure it’s one of many inputs shaping a child’s political identity.

A comparative lens reveals the global universality of this phenomenon. In countries with strong multi-generational party loyalties, like India or Italy, family influence is amplified by cultural norms. Conversely, in nations with fluid party systems, such as the Netherlands, familial impact is often tempered by broader societal discourse. This suggests that while family is a foundational factor, its strength varies based on cultural and systemic contexts. Understanding these nuances allows for more tailored interventions, whether in civic education or media literacy programs, to encourage informed rather than inherited partisanship.

Ultimately, family influence on political predisposition is a double-edged sword. It provides a foundational framework for understanding the world but risks limiting intellectual growth if unchecked. By acknowledging its power and adopting strategies to promote critical engagement, parents and educators can transform this predisposition from a rigid mold into a flexible starting point. After all, the goal of political socialization isn’t conformity but the cultivation of thoughtful, engaged citizens capable of evolving beyond their initial beliefs.

Why Political Discussion Matters: Shaping Society Through Open Dialogue

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A predisposed factor to political party affiliation is a characteristic or condition that makes an individual more likely to align with a particular political party, often due to inherent or early-life influences.

Family background influences predisposition to a political party through socialization, as parents and relatives often pass down their political beliefs, values, and party loyalties to younger generations.

Yes, socioeconomic status can be a predisposed factor, as individuals from different income levels, education backgrounds, or occupations often align with parties that address their specific economic interests or concerns.

Yes, geographic location plays a role, as regional cultures, histories, and local issues often shape political leanings, leading individuals in certain areas to be predisposed to specific parties.