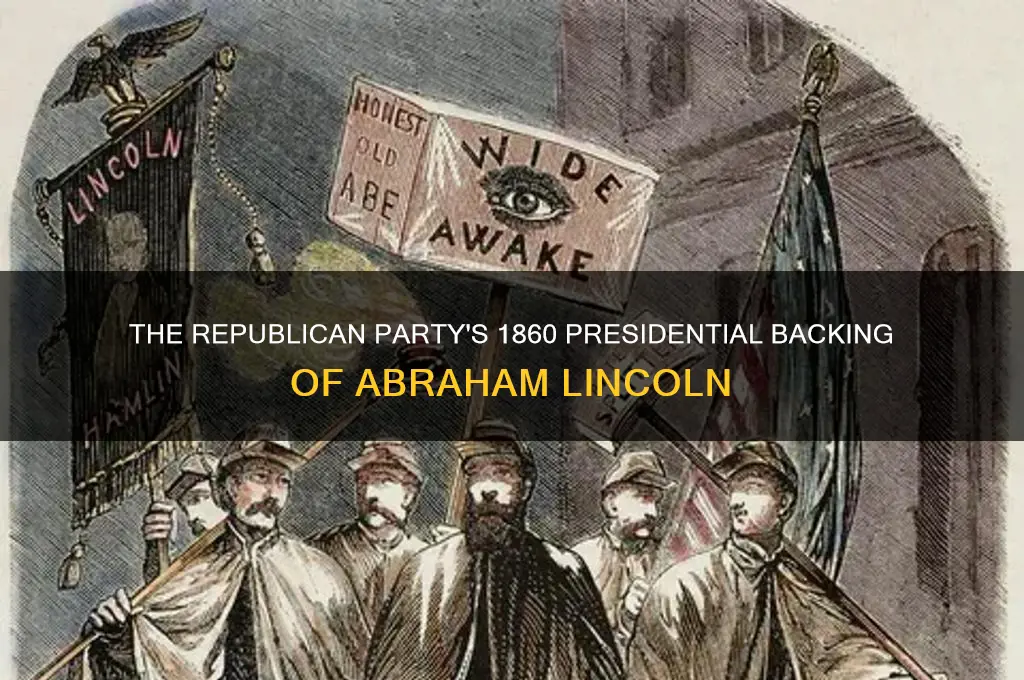

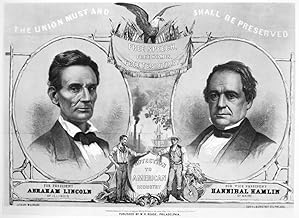

In the 1860 U.S. presidential election, Abraham Lincoln was supported by the Republican Party, which had emerged as a major political force in the 1850s, primarily opposing the expansion of slavery into new territories. Lincoln’s nomination and subsequent victory were pivotal, as the election highlighted deep divisions over slavery and states' rights. The Republican Party’s platform, which included preventing the spread of slavery and promoting economic modernization, resonated with Northern voters, while Southern states viewed Lincoln’s election as a threat to their way of life, ultimately leading to secession and the Civil War.

Explore related products

$36.47 $49.99

What You'll Learn

- Republican Party's Platform: Emphasized anti-slavery, homesteading, and internal improvements, aligning with Lincoln's views

- Key Figures in Support: Leaders like William Seward and Thaddeus Stevens backed Lincoln's nomination

- Convention Dynamics: Lincoln secured the nomination on the third ballot in Chicago

- Opposition to Democrats: Democrats split, weakening their candidacy and aiding Lincoln's victory

- Regional Support Base: Strong backing from Northern states, crucial for his electoral success

Republican Party's Platform: Emphasized anti-slavery, homesteading, and internal improvements, aligning with Lincoln's views

The Republican Party's platform in 1860 was a bold statement of principles that directly aligned with Abraham Lincoln's vision for the nation. At its core, the platform emphasized three key pillars: anti-slavery, homesteading, and internal improvements. These were not mere political talking points but a cohesive strategy to address the pressing issues of the time. Anti-slavery, the most contentious issue, was framed not just as a moral imperative but as a necessary step to preserve the Union. The Republicans argued that preventing the expansion of slavery into new territories would limit its influence and ultimately lead to its decline. This stance resonated deeply with Lincoln, who famously declared, "A house divided against itself cannot stand."

Homesteading, another central plank, offered a practical solution to the economic and social challenges of the era. The Homestead Act, which the Republicans championed, promised 160 acres of public land to anyone willing to cultivate it for five years. This policy aimed to encourage westward expansion, create self-sufficient farmers, and reduce urban overcrowding. For Lincoln, homesteading was a way to democratize land ownership and provide opportunities for ordinary Americans, aligning with his belief in the dignity of labor and the potential of the common man. It was a forward-thinking policy that sought to build a nation of independent, prosperous citizens.

Internal improvements, the third pillar, focused on infrastructure development, including roads, railroads, and canals. The Republicans recognized that a modern transportation network was essential for economic growth and national unity. Lincoln, a longtime advocate for infrastructure investment, saw these improvements as a means to connect the country physically and economically. He famously referred to such projects as "binding the nation together" and believed they would foster trade, communication, and a shared sense of purpose. This commitment to internal improvements was not just about building roads and rails but about constructing a stronger, more cohesive nation.

What set the Republican platform apart was its ability to weave these three principles into a unified vision. Anti-slavery provided the moral foundation, homesteading offered economic opportunity, and internal improvements ensured the nation’s physical and economic integration. Together, they reflected Lincoln’s belief in a nation where freedom, hard work, and progress were intertwined. This platform was not merely a political strategy but a blueprint for a future where the United States could thrive as a united, just, and prosperous republic.

In practical terms, the Republican platform of 1860 was a call to action for voters who shared Lincoln’s ideals. It invited them to support a party that stood against the expansion of slavery, promoted land ownership for the working class, and invested in the nation’s infrastructure. For those considering the impact of their vote, the platform offered a clear choice: a future shaped by these principles or a continuation of the status quo. By aligning so closely with Lincoln’s views, the Republicans not only secured his presidency but also laid the groundwork for transformative policies that would define the nation’s trajectory for decades to come.

Understanding Texas Political Parties: Key Roles and Functions Explained

You may want to see also

Key Figures in Support: Leaders like William Seward and Thaddeus Stevens backed Lincoln's nomination

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, and Abraham Lincoln's rise to the presidency was significantly bolstered by key figures within the Republican Party. Among these, William Seward and Thaddeus Stevens stood out as influential leaders whose support was instrumental in securing Lincoln's nomination. Their backing was not merely symbolic; it represented a strategic alignment of interests and ideologies that would shape the course of the nation.

William Seward, a prominent senator from New York and a leading figure in the Republican Party, initially entered the 1860 Republican National Convention as the frontrunner for the presidential nomination. Despite his strong credentials and national recognition, Seward faced significant opposition from certain factions within the party. His outspoken views on slavery and his association with radical abolitionists made him a polarizing figure. However, Seward's decision to gracefully step aside and throw his support behind Lincoln demonstrated his commitment to party unity and his recognition of Lincoln's broader appeal. This strategic move not only solidified Lincoln's position but also showcased Seward's political acumen and willingness to prioritize the greater good over personal ambition.

Thaddeus Stevens, a congressman from Pennsylvania, brought a different but equally vital dimension to Lincoln's support base. Known for his uncompromising stance against slavery and his advocacy for equal rights, Stevens represented the radical wing of the Republican Party. His endorsement of Lincoln was crucial in rallying the party's more progressive members, who were initially skeptical of Lincoln's moderate reputation. Stevens' support helped bridge the gap between the party's factions, ensuring that Lincoln could appeal to both moderate and radical Republicans. This unity was essential in a time of deep national division, as it allowed the party to present a cohesive front against the Democratic Party and the emerging Southern secessionist movement.

The combined efforts of Seward and Stevens highlight the importance of leadership in political campaigns. Their ability to set aside personal differences and work toward a common goal was a testament to their dedication to the principles of the Republican Party and their vision for the nation. Seward's pragmatic approach and Stevens' ideological fervor complemented each other, creating a balanced and effective support system for Lincoln. Their roles in Lincoln's nomination underscore the idea that successful political movements often require the collaboration of diverse personalities and perspectives.

In practical terms, the support of figures like Seward and Stevens provided Lincoln with more than just votes; it offered him credibility, strategic guidance, and access to influential networks. Seward's experience in national politics and Stevens' grassroots connections were invaluable assets in navigating the complexities of the 1860 election. For modern political campaigns, this serves as a reminder of the importance of cultivating relationships with key figures who can bring unique strengths and constituencies to the table. By leveraging such alliances, candidates can enhance their appeal, build broader coalitions, and ultimately increase their chances of success. The lessons from Seward and Stevens' support of Lincoln remain relevant, offering insights into the dynamics of leadership, unity, and strategic collaboration in achieving political victories.

Populist Party's Political Reform Strategies: Engaging the Masses for Change

You may want to see also

1860 Convention Dynamics: Lincoln secured the nomination on the third ballot in Chicago

The 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago was a crucible of political maneuvering, ideological division, and strategic compromise. Abraham Lincoln’s nomination on the third ballot was no accident; it was the result of meticulous planning, regional alliances, and the fragmentation of his opponents. Lincoln’s campaign managers, led by David Davis, executed a strategy that leveraged his strength in the Midwest while neutralizing rivals like William Seward, Salmon Chase, and Simon Cameron. By positioning Lincoln as a moderate alternative, they avoided alienating factions within the party, particularly those wary of Seward’s radical reputation on slavery.

Consider the mechanics of the convention: Lincoln started with 102 votes on the first ballot, far behind Seward’s 173. However, Seward’s inability to secure a majority exposed his vulnerabilities. Chase and Cameron’s supporters, recognizing Seward’s stagnation, began shifting their allegiance. Lincoln’s team capitalized on this by emphasizing his electability in critical Northern states and his appeal to former Whigs. By the third ballot, Lincoln surged to 349 votes, clinching the nomination. This outcome underscores the importance of backroom deals, delegate persuasion, and the art of political timing.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark contrast between Lincoln’s nomination and the Democratic Party’s chaotic convention that same year. While the Republicans united behind a single candidate after three ballots, the Democrats splintered into Northern and Southern factions, ultimately nominating two candidates. This highlights the Republicans’ organizational discipline and their ability to prioritize unity over individual ambition. Lincoln’s nomination was not just a victory for him but a testament to the party’s strategic coherence in the face of national division.

For those studying political campaigns or organizing conventions, the 1860 Republican National Convention offers actionable lessons. First, cultivate a candidate who can bridge ideological gaps within the party. Second, focus on delegate management—understand their priorities and address their concerns. Third, monitor opponents’ weaknesses and exploit them strategically. Lincoln’s nomination demonstrates that success in such high-stakes environments requires more than popularity; it demands tactical acumen and a deep understanding of the political landscape.

Finally, the dynamics of the 1860 convention serve as a historical case study in coalition-building. Lincoln’s team forged alliances with Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Illinois delegates, ensuring a solid base of support. They also appealed to anti-Seward sentiment, particularly among delegates from the lower North. This approach transformed Lincoln from a regional candidate into a national figure. Modern political operatives can emulate this by identifying and mobilizing key constituencies, framing their candidate as a unifying force, and leveraging divisions among opponents to secure victory.

Why Politicians Often Ignore the Urgent Threat of Global Warming

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Opposition to Democrats: Democrats split, weakening their candidacy and aiding Lincoln's victory

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, and the Democratic Party's internal divisions played a crucial role in Abraham Lincoln's victory. The Democrats, who had dominated national politics for decades, found themselves fractured over the issue of slavery, with deep ideological differences between Northern and Southern factions. This split not only weakened their candidacy but also created an opportunity for the Republican Party, led by Lincoln, to emerge as a viable alternative.

The Democratic Schism: A Recipe for Disaster

The Democratic Party’s inability to unite behind a single candidate in 1860 was its undoing. Northern Democrats, who leaned toward moderation on slavery, supported Stephen A. Douglas, while Southern Democrats, staunchly pro-slavery, backed John C. Breckinridge. A third faction, the Constitutional Union Party, formed to appeal to Southern moderates, further splintered the vote. This fragmentation ensured that the Democratic vote was divided, allowing Lincoln to win the election with only 39.8% of the popular vote but a clear majority in the Electoral College.

Regional Tensions and Ideological Clashes

The root of the Democratic split lay in the irreconcilable differences between Northern and Southern Democrats. Northerners, influenced by industrialization and a growing abolitionist movement, were less willing to defend slavery outright. Southerners, on the other hand, saw slavery as essential to their agrarian economy and way of life. These regional tensions were exacerbated by the Supreme Court’s *Dred Scott* decision in 1857, which further polarized the party. The inability to bridge this ideological gap left the Democrats vulnerable, as Lincoln’s Republican Party capitalized on the growing anti-slavery sentiment in the North.

Strategic Missteps and Missed Opportunities

The Democrats’ failure to present a unified front was compounded by strategic missteps. Stephen Douglas’s attempts to appeal to both Northern and Southern voters through his "popular sovereignty" stance alienated extremists on both sides. Meanwhile, Southern Democrats’ insistence on federal protection for slavery pushed moderate voters away. The party’s inability to adapt its message to a rapidly changing political landscape handed the Republicans a strategic advantage. Lincoln’s campaign, focused on preventing the expansion of slavery, resonated with Northern voters and positioned him as a pragmatic alternative to the fractured Democrats.

The Electoral Math: How Division Cost the Democrats the Election

A closer look at the electoral math reveals the devastating impact of the Democratic split. Had the Democrats united behind a single candidate, they could have easily surpassed Lincoln’s vote total. Instead, Douglas, Breckinridge, and Constitutional Union candidate John Bell collectively garnered over 60% of the popular vote. In key states like Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Indiana, the divided Democratic vote allowed Lincoln to secure victories with pluralities rather than majorities. This mathematical reality underscores how internal opposition within the Democratic Party directly contributed to Lincoln’s win.

Lessons for Modern Politics: Unity Matters

The 1860 election offers a timeless lesson: unity is essential for political success. Parties that fail to bridge internal divisions risk ceding power to their opponents. For modern political strategists, the Democratic split serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of prioritizing ideological purity over coalition-building. In an era of increasing polarization, the ability to find common ground within a party—or at least present a unified front—remains critical for electoral viability. The Democrats’ failure in 1860 was not just a loss of an election but a catalyst for the Civil War, highlighting the high stakes of political disunity.

Are Local Political Parties Tax-Exempt? Understanding the Legal Framework

You may want to see also

Regional Support Base: Strong backing from Northern states, crucial for his electoral success

Abraham Lincoln's presidential victory in 1860 hinged on a robust regional support base, particularly from the Northern states. This backing was not merely a matter of geographical preference but a reflection of deep-seated political, economic, and social alignments. The North, with its burgeoning industrial economy and growing opposition to the expansion of slavery, found a champion in Lincoln. His platform, which emphasized the preservation of the Union and the containment of slavery, resonated strongly with Northern voters. This regional support was crucial, as it provided the electoral college votes necessary to secure his presidency, despite his lack of support in the South.

To understand the significance of this regional backing, consider the electoral map of 1860. Lincoln won every Northern state except New Jersey, which split its electoral votes. This near-unanimous support from the North was a testament to the Republican Party's effective mobilization of its base. The party's focus on issues like tariffs, internal improvements, and the moral argument against slavery aligned perfectly with Northern interests. For instance, the tariff issue was particularly salient, as Northern manufacturers sought protection from foreign competition, a policy Lincoln supported. This economic alignment, coupled with the moral imperative to limit slavery, created a powerful coalition that propelled Lincoln to victory.

A comparative analysis of the 1860 election reveals the stark contrast between Northern and Southern support. While Lincoln garnered 180 electoral votes, primarily from the North, his opponents—Stephen A. Douglas, John C. Breckinridge, and John Bell—split the Southern vote. This division among Southern candidates highlighted the region's lack of a unified front, which ultimately benefited Lincoln. The North's cohesive support, in contrast, demonstrated the effectiveness of the Republican Party's strategy in rallying its regional base. This regional solidarity was not just a numbers game but a reflection of the North's commitment to the principles Lincoln represented.

Practical insights into this regional support base can be gleaned from the campaign strategies employed by the Republican Party. The party utilized a variety of tactics to solidify Northern backing, including extensive stump speeches, distribution of pamphlets, and the use of new communication technologies like the telegraph. These efforts were tailored to address the specific concerns of Northern voters, such as economic prosperity and the moral stance against slavery. For example, Lincoln's Cooper Union address in New York City was a pivotal moment, as it articulated a clear and compelling case against the expansion of slavery, resonating deeply with Northern audiences.

In conclusion, the strong backing from the Northern states was not just a regional preference but a strategic and ideological alignment that proved decisive in Abraham Lincoln's 1860 presidential victory. This support base was cultivated through a combination of economic policies, moral arguments, and effective campaign strategies that addressed the unique interests and values of the North. Understanding this regional dynamic offers valuable insights into the political landscape of the time and the factors that contribute to electoral success. For modern political campaigns, the lesson is clear: a focused, region-specific approach that aligns with the values and interests of the target electorate can be a powerful tool in securing victory.

ESPN's Political Shift: How Sports Media Embraced Social Commentary

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Republican Party supported Abraham Lincoln for president in 1860.

No, Abraham Lincoln was not a member of the Democratic Party; he was the candidate of the Republican Party in 1860.

No, the Whig Party had largely dissolved by 1860, and Abraham Lincoln ran as the candidate of the Republican Party.

While the Republican Party was his primary support, some members of the Constitutional Union Party and anti-Democratic factions also backed Lincoln in certain regions.

![Republican "Campaign" Text-Book, for the Year 1860 1860 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)