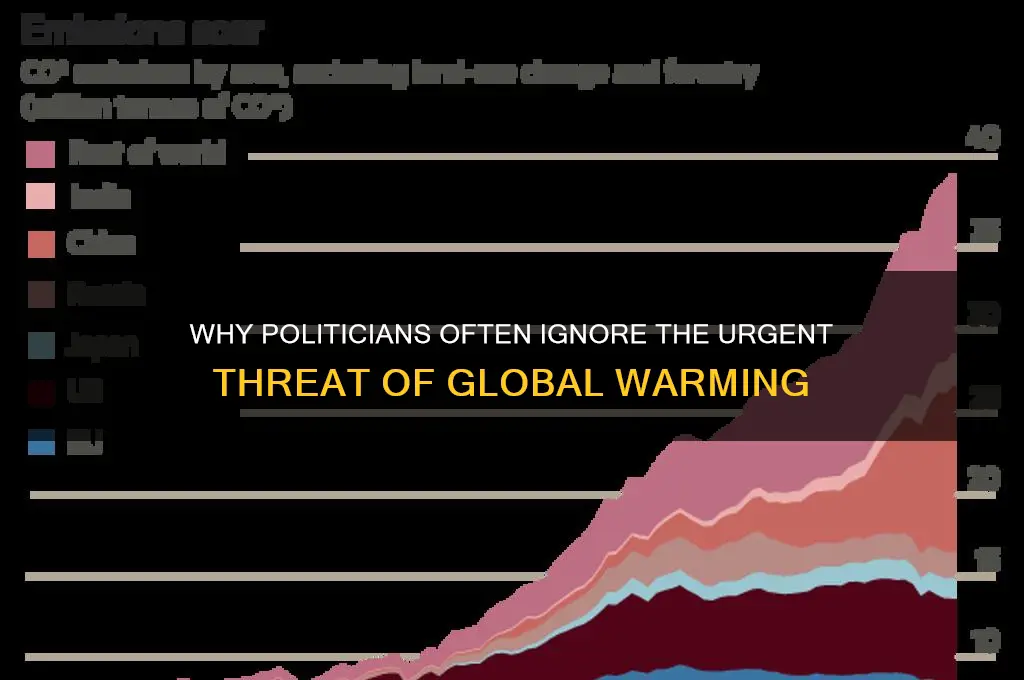

The notion that politicians want global warming is a contentious and often misleading claim that oversimplifies the complex interplay between politics, economics, and environmental policy. While some political actors may prioritize short-term economic gains or align with industries resistant to climate action, it is inaccurate to generalize that all politicians actively desire global warming. Instead, political stances on climate change often reflect competing interests, ideological differences, and varying levels of scientific acceptance. For instance, politicians tied to fossil fuel industries may oppose stringent climate policies to protect economic stability, while others may downplay the urgency of global warming due to skepticism or electoral pressures. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for addressing the barriers to effective climate action and fostering informed public discourse.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Economic Interests: Protecting fossil fuel industries and related jobs drives political resistance to climate action

- Short-Term Gains: Politicians prioritize immediate economic growth over long-term environmental sustainability

- Lobbying Power: Corporate influence shapes policies to favor industries contributing to global warming

- Voter Apathy: Public indifference allows politicians to avoid addressing climate change effectively

- Geopolitical Control: Dominance over energy resources maintains global political and economic power

Economic Interests: Protecting fossil fuel industries and related jobs drives political resistance to climate action

The resistance to climate action from certain political factions is often deeply rooted in economic interests, particularly the protection of fossil fuel industries and the jobs they provide. Fossil fuels—coal, oil, and natural gas—remain a cornerstone of global energy production, and industries reliant on these resources wield significant political and economic power. For politicians, supporting these industries can mean securing campaign funding, maintaining regional economic stability, and avoiding backlash from powerful corporate interests. As a result, policies that threaten the fossil fuel sector, such as carbon taxes or renewable energy mandates, are often met with fierce opposition. This resistance is not merely ideological but is driven by the tangible economic benefits these industries provide to specific regions, communities, and political donors.

One of the primary concerns for politicians is the potential loss of jobs in fossil fuel-dependent regions. Industries like coal mining, oil extraction, and natural gas production employ millions of workers worldwide, often in areas where alternative economic opportunities are limited. Transitioning to renewable energy sources would inevitably disrupt these labor markets, leading to job losses and economic hardship for communities that have long relied on these industries. Politicians representing these regions are therefore incentivized to resist climate policies that could harm their constituents' livelihoods. This resistance is often framed as a defense of working-class jobs, even if it delays necessary action to address global warming.

Additionally, the fossil fuel industry generates substantial revenue through taxes, royalties, and export earnings, which many governments rely on to fund public services and infrastructure. For example, oil-exporting nations and states with significant fossil fuel reserves often depend on these revenues to balance their budgets. Politicians in these regions are reluctant to adopt policies that could reduce this income stream, as it would require finding alternative sources of revenue or cutting public spending—both politically risky moves. This economic dependency creates a strong incentive to maintain the status quo, even as the scientific consensus on climate change grows more urgent.

Corporate lobbying also plays a critical role in shaping political resistance to climate action. Fossil fuel companies invest heavily in lobbying efforts to influence legislation and regulatory decisions in their favor. These companies fund political campaigns, sponsor think tanks, and employ public relations strategies to cast doubt on the severity of climate change or the feasibility of renewable energy alternatives. By framing climate action as a threat to economic prosperity, these industries effectively sway public opinion and pressure politicians to prioritize short-term economic gains over long-term environmental sustainability.

Finally, the global nature of the fossil fuel industry complicates efforts to implement climate policies. Politicians in countries with significant fossil fuel reserves or export capabilities often fear that unilateral action could put their industries at a competitive disadvantage in the global market. This concern is particularly acute in regions where fossil fuels are a major driver of economic growth and geopolitical influence. As a result, international cooperation on climate action is often hindered by competing economic interests, as nations prioritize protecting their domestic industries over collective global goals.

In summary, economic interests—particularly the protection of fossil fuel industries and related jobs—are a major driver of political resistance to climate action. The reliance on fossil fuels for employment, revenue, and political support creates powerful incentives for politicians to delay or weaken policies aimed at addressing global warming. Overcoming this resistance requires not only addressing the economic concerns of affected communities but also implementing policies that provide a just transition to renewable energy, ensuring that workers and regions dependent on fossil fuels are not left behind.

How Political Parties Act as Linkage Institutions in Democracy

You may want to see also

Short-Term Gains: Politicians prioritize immediate economic growth over long-term environmental sustainability

The allure of short-term economic gains often proves irresistible to politicians, leading them to prioritize immediate growth over the long-term health of the planet. This is a key factor in understanding why some political actors may be perceived as wanting, or at least tolerating, global warming. The pressure to deliver tangible results within election cycles creates a strong incentive to focus on policies that stimulate economic activity, even if those policies contribute to environmental degradation. For instance, supporting fossil fuel industries, which are major contributors to greenhouse gas emissions, can provide a quick boost to employment and GDP, making it an attractive option for politicians seeking to demonstrate their effectiveness.

In many cases, politicians advocate for industries that are significant sources of carbon emissions, such as coal, oil, and gas, because these sectors provide substantial revenue and jobs in the short term. By promoting these industries, politicians can claim credit for economic growth and job creation, which are powerful messages during election campaigns. However, this approach often comes at the expense of investing in renewable energy and sustainable practices that could mitigate climate change but may not yield immediate economic benefits. The focus on short-term gains also reflects a broader political strategy to maintain support from powerful interest groups and constituents who benefit directly from these industries.

Another aspect of this short-term focus is the reluctance to implement policies that could slow economic growth, even if they are necessary for environmental sustainability. Measures like carbon taxes, stricter emissions regulations, or subsidies for green technologies often face opposition because they can increase costs for businesses and consumers in the near term. Politicians may fear that such policies will be unpopular and could lead to electoral backlash, especially in regions heavily dependent on polluting industries. As a result, they may delay or weaken environmental regulations, prioritizing the immediate economic and political benefits over the long-term consequences of climate change.

Furthermore, the complexity and long-term nature of climate change make it a less compelling issue for politicians compared to more immediate concerns like unemployment, inflation, or public safety. Addressing global warming requires significant upfront investments and may not yield visible results for years or even decades. This time lag between action and outcome makes it difficult for politicians to justify spending political capital on climate policies when they could instead focus on issues that provide more immediate returns. The political calculus often favors short-term gains, even if it means exacerbating a global crisis that will affect future generations.

Lastly, the global nature of climate change adds another layer of complexity, as politicians may feel that their actions have little impact on a problem that requires international cooperation. This can lead to a "free-rider" mentality, where countries or leaders hesitate to take ambitious climate action unless others do the same. In such a scenario, politicians might prioritize domestic economic interests, arguing that their country should not bear the costs of reducing emissions if others are not doing their part. This mindset further reinforces the tendency to focus on short-term economic growth, even as the need for global environmental stewardship becomes increasingly urgent.

Exploring the Origins and Impact of Political Doctrines Throughout History

You may want to see also

Lobbying Power: Corporate influence shapes policies to favor industries contributing to global warming

The influence of corporate lobbying on political decisions related to global warming is a significant factor in understanding why certain policies seem to favor industries that contribute to climate change. Corporations, particularly those in the fossil fuel, automotive, and manufacturing sectors, wield substantial lobbying power, enabling them to shape legislation and regulatory frameworks in their favor. These industries often argue that stringent environmental regulations could harm economic growth, job creation, and competitiveness, leveraging these concerns to gain political support. By framing the debate in terms of economic survival, they effectively shift the narrative away from the urgent need to address climate change, ensuring that policies remain favorable to their continued operation and profitability.

One of the most direct ways corporate lobbying influences policy is through campaign financing and direct access to policymakers. Companies and industry groups invest heavily in political campaigns, often securing favorable treatment in return. This quid pro quo relationship results in lawmakers being more inclined to support legislation that aligns with the interests of their financial backers. For instance, fossil fuel companies have historically funded political campaigns and think tanks that promote climate skepticism or advocate for deregulation. This financial influence not only shapes the political agenda but also creates a barrier to the implementation of robust climate policies that could reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Lobbying efforts also extend to the manipulation of public perception and policy discourse. Corporations often fund studies, media campaigns, and advocacy groups that cast doubt on the scientific consensus around climate change or exaggerate the economic costs of transitioning to cleaner energy sources. By sowing uncertainty and fear, these efforts delay or weaken regulatory actions. Additionally, industry lobbyists frequently push for loopholes, exemptions, or voluntary compliance measures in environmental legislation, ensuring that their operations face minimal disruption. This strategic shaping of public and political opinion allows industries to maintain the status quo, even as the scientific evidence for urgent climate action grows stronger.

Another critical aspect of corporate lobbying is the promotion of false solutions or incremental changes that appear to address climate change without fundamentally altering business models. For example, industries may advocate for carbon capture technologies, biofuels, or offset schemes that allow them to continue emitting greenhouse gases while claiming progress. These measures often serve as distractions from more effective solutions, such as phasing out fossil fuels or implementing strict emissions caps. By positioning themselves as part of the solution, corporations can maintain their influence over policy discussions and avoid more transformative changes that could threaten their interests.

Finally, the global nature of corporate lobbying exacerbates the challenge of addressing climate change. Multinational corporations often exploit differences in national regulations to lobby against harmonized global standards, arguing that such measures would put them at a competitive disadvantage. This fragmentation of policies allows industries to continue high-emission practices in regions with weaker environmental regulations, undermining global efforts to combat climate change. The result is a political landscape where corporate interests frequently take precedence over the collective need to reduce global warming, highlighting the profound impact of lobbying power on climate policy.

Ben Shapiro's Political Party: Unraveling His Conservative Affiliations and Beliefs

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Voter Apathy: Public indifference allows politicians to avoid addressing climate change effectively

Voter apathy, or public indifference toward climate change, has become a significant enabler for politicians to sidestep meaningful action on global warming. When the electorate fails to prioritize environmental issues, politicians often respond by deprioritizing them as well. This dynamic creates a self-perpetuating cycle: politicians avoid taking bold climate action because they perceive it as politically risky, while the public remains unengaged due to a lack of visible political leadership. As a result, climate change is often relegated to the periphery of political agendas, allowing politicians to focus on more immediately "winnable" issues that resonate with their voter base.

One of the primary reasons voter apathy persists is the abstract and long-term nature of climate change. Unlike immediate economic concerns or social issues, the impacts of global warming are often perceived as distant, both temporally and geographically. This perception reduces the urgency of the issue in the minds of many voters, who may feel that addressing climate change can be postponed without immediate consequences. Politicians exploit this mindset by framing climate action as a luxury rather than a necessity, arguing that resources should be allocated to more pressing, tangible problems. This narrative effectively shifts the focus away from environmental policies, allowing politicians to maintain the status quo without facing significant backlash.

Public indifference also allows politicians to cater to powerful interest groups that benefit from the continuation of fossil fuel-dependent economies. Industries such as oil, gas, and coal wield considerable political influence through lobbying, campaign contributions, and job creation in key electoral districts. When voters are apathetic about climate change, politicians face little pressure to challenge these industries or implement policies that might disrupt their profits. Instead, they can justify inaction by pointing to economic concerns or energy security, knowing that the electorate is unlikely to hold them accountable for prioritizing short-term gains over long-term sustainability.

Moreover, voter apathy undermines the formation of a strong, unified demand for climate action. Without a vocal and engaged constituency pushing for environmental policies, politicians lack the political incentive to take risks or make sacrifices. This is particularly evident in systems where voter turnout is low or where climate change is not a decisive factor in electoral decisions. In such contexts, politicians can afford to pay lip service to environmental concerns while avoiding substantive change, knowing that their reelection prospects remain largely unaffected. This lack of accountability perpetuates a political environment where climate change is treated as a secondary issue rather than an existential threat.

Finally, the media's role in shaping public opinion cannot be overlooked. When climate change receives limited coverage or is portrayed as a divisive or controversial topic, public interest wanes. Politicians are keenly aware of this dynamic and often tailor their messaging to align with dominant media narratives. If the public is indifferent, politicians can safely avoid taking a strong stance on climate change without fear of negative media attention. This further entrenches the issue in a cycle of neglect, as media coverage remains minimal and public awareness remains low. Breaking this cycle requires a concerted effort to educate and engage voters, making climate change a central concern in political discourse and electoral decision-making. Without such a shift, politicians will continue to exploit voter apathy to avoid addressing global warming effectively.

Greenland's European Political Ties: Historical, Cultural, and Strategic Reasons

You may want to see also

Geopolitical Control: Dominance over energy resources maintains global political and economic power

The concept of geopolitical control through energy dominance is a critical aspect of understanding the political motivations behind certain stances on global warming. In the context of international relations, energy resources have long been recognized as a powerful tool for exerting influence and maintaining global power. Fossil fuels, in particular, have been at the heart of geopolitical strategies, with nations vying for control over oil and gas reserves to secure their economic and political interests. This dynamic has significant implications for the global response to climate change, as the transition to a low-carbon economy threatens to disrupt the existing power structures.

In the current global energy landscape, a few nations possess a disproportionate share of fossil fuel reserves, granting them substantial leverage in the international arena. For instance, countries in the Middle East, such as Saudi Arabia and Iran, have historically used their vast oil wealth to shape foreign policies and forge strategic alliances. Similarly, Russia's control over natural gas supplies has enabled it to exert influence over European nations, leveraging energy exports as a geopolitical tool. This control over energy resources translates into political and economic power, allowing these nations to negotiate favorable trade deals, secure military alliances, and maintain a strong position in global decision-making processes. As the world grapples with the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the prospect of diminishing the value of these fossil fuel assets becomes a significant concern for these energy-rich countries.

The resistance to acknowledging and addressing global warming can be partly attributed to the desire of certain political entities to preserve their dominance in the energy sector. By downplaying the urgency of climate action, these powers aim to prolong the relevance and demand for fossil fuels, thereby safeguarding their economic and geopolitical interests. This strategy often involves lobbying against renewable energy initiatives, promoting fossil fuel-based technologies, and influencing international climate negotiations to favor their agenda. For example, some political groups advocate for the continued use of coal, oil, and gas, emphasizing energy security and economic growth while undermining the scientific consensus on climate change. This approach not only delays the implementation of effective climate policies but also ensures that the existing power dynamics, centered around fossil fuel control, remain intact.

Furthermore, the geopolitical implications of a transition to renewable energy sources are complex. While this shift has the potential to democratize energy production and reduce the influence of traditional energy superpowers, it also creates new opportunities for geopolitical maneuvering. Countries with abundant renewable resources, such as solar and wind potential, may emerge as new energy leaders, reshaping global power structures. However, the initial stages of this transition could be manipulated to serve existing power interests. For instance, dominant nations might invest in renewable technologies while simultaneously controlling the supply chains and infrastructure, thereby maintaining their grip on the global energy market. This scenario highlights the intricate relationship between energy, politics, and the environment, where the desire for geopolitical control can significantly influence the pace and direction of climate action.

In the pursuit of global political and economic power, the control of energy resources remains a pivotal strategy. The intersection of energy dominance and climate politics reveals a complex web of interests and motivations. As the world navigates the challenges of global warming, understanding these geopolitical dynamics is essential to deciphering the resistance and inertia observed in certain political circles. Addressing climate change effectively requires not only scientific and technological solutions but also a careful consideration of the power structures and incentives that shape global energy policies. This includes fostering international cooperation, promoting transparent energy governance, and ensuring a just transition that accounts for the geopolitical realities of energy-rich nations.

Roswell's Political Divide: Unraveling the Alien Conspiracy and Its Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Some politicians deny or downplay global warming due to economic interests, ideological beliefs, or pressure from industries reliant on fossil fuels. Acknowledging climate change often requires policy changes that could disrupt these industries, leading to resistance.

Politics often focuses on short-term economic gains because politicians operate within electoral cycles, prioritizing immediate benefits for constituents and donors. Long-term climate solutions may involve costs or disruptions that are politically unpopular in the near term.

Opposition to climate policies often stems from concerns about job losses in traditional industries, fears of increased government regulation, or alignment with free-market ideologies. These parties may also be influenced by lobbying efforts from fossil fuel companies.

Implementing global climate agreements can be challenging due to differing national priorities, sovereignty concerns, and the lack of enforceable mechanisms. Political leaders may also face domestic opposition, making it difficult to commit to or uphold international pledges.