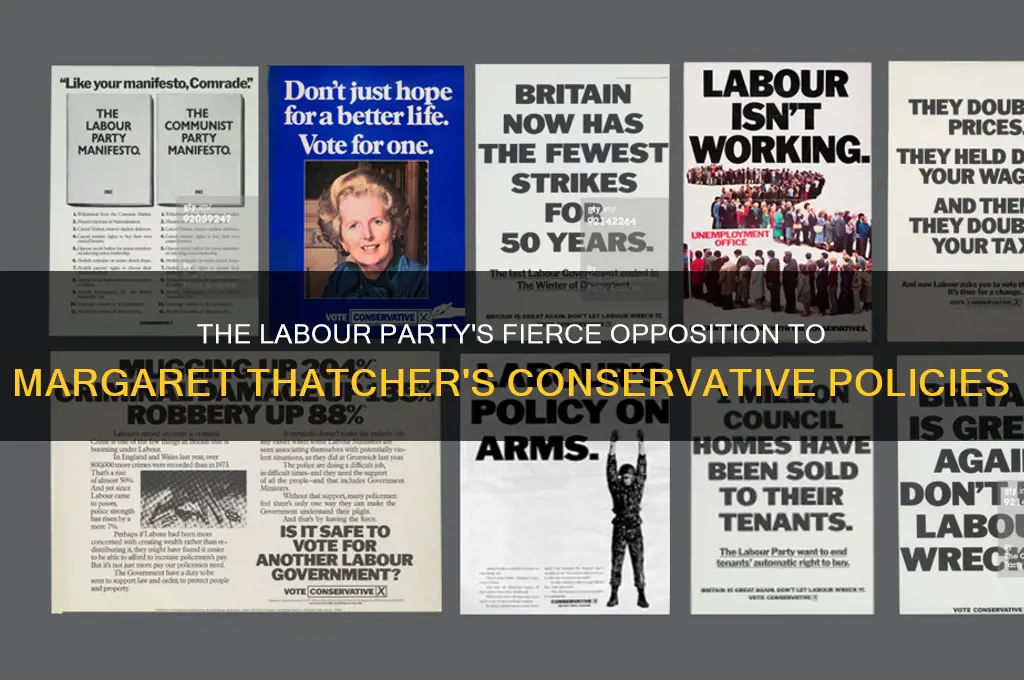

Margaret Thatcher, the former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, faced significant opposition from the Labour Party during her tenure from 1979 to 1990. As the leader of the Conservative Party, Thatcher's policies, often referred to as Thatcherism, were characterized by deregulation, privatization, and a reduction in the power of trade unions, which starkly contrasted with the Labour Party's traditional emphasis on social welfare, public ownership, and workers' rights. The Labour Party, led by figures such as Michael Foot, Neil Kinnock, and later John Smith, consistently challenged Thatcher's government, particularly on issues like industrial relations, economic inequality, and the impact of her policies on the working class. Their opposition was a defining feature of British politics during the 1980s, culminating in intense debates and electoral contests that shaped the nation's political landscape.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Labour Party |

| Ideology | Social democracy, democratic socialism |

| Position | Centre-left |

| Leader during Thatcher Era | Michael Foot (1980–1983), Neil Kinnock (1983–1992) |

| Key Policies | Nationalization, workers' rights, public services, wealth redistribution |

| Opposition to Thatcher | Criticized privatization, austerity, and union policies |

| Election Performance | Lost general elections in 1979, 1983, 1987, and 1992 |

| Current Status | Major opposition party in the UK (as of latest data) |

| Notable Figures | Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, Keir Starmer |

| International Affiliation | Progressive Alliance, Party of European Socialists |

Explore related products

$28.11 $36.99

$9.99 $11.99

$46.96 $65

What You'll Learn

- Labour Party: Main opposition, led by figures like Michael Foot and Neil Kinnock during Thatcher's tenure

- Liberal Democrats: Merged party opposing Thatcher's policies on economy, social issues, and governance

- Trade Unions: Strongly resisted Thatcher's anti-union policies and privatization efforts throughout her leadership

- Scottish National Party (SNP): Opposed Thatcher's policies, particularly their impact on Scotland's economy and culture

- Left-Wing Activists: Grassroots movements and protests against Thatcher's austerity and conservative social policies

Labour Party: Main opposition, led by figures like Michael Foot and Neil Kinnock during Thatcher's tenure

The Labour Party stood as the primary opposition to Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government throughout her tenure as Prime Minister (1979–1990). During this period, the Labour Party was led by figures such as Michael Foot and Neil Kinnock, each bringing distinct styles and strategies to the challenge of countering Thatcher's dominant political agenda. Their leadership reflected the party's internal struggles and ideological shifts in response to Thatcherism, which reshaped Britain's economic and social landscape.

Michael Foot, a veteran left-wing intellectual, led the Labour Party from 1980 to 1983. His tenure was marked by a commitment to traditional socialist principles, including nationalization, workers' rights, and opposition to nuclear disarmament. However, Foot's leadership coincided with a period of deep division within the party. The rise of the Social Democratic Party (SDP), formed by centrist Labour MPs in 1981, splintered Labour's support and weakened its electoral prospects. Foot's idealism, while admired by the party's left wing, struggled to resonate with a broader electorate increasingly drawn to Thatcher's neoliberal policies. The 1983 general election resulted in a landslide victory for the Conservatives, with Labour suffering its worst performance since the 1930s. This defeat underscored the challenges of maintaining a left-wing agenda in the face of Thatcher's transformative policies.

Neil Kinnock took over as Labour leader in 1983, inheriting a party in crisis. Kinnock's leadership was characterized by a pragmatic effort to modernize Labour, moving it away from its more radical policies while retaining a commitment to social justice. He sought to address the party's internal divisions and rebuild its credibility as a viable alternative to Thatcherism. Kinnock's speeches, such as his famous 1985 conference address condemning Militant Tendency, signaled a break from the party's far-left elements. However, despite these efforts, Labour remained unable to defeat Thatcher in the 1987 general election, though it did improve its position compared to 1983. Kinnock's leadership laid the groundwork for the party's eventual shift toward New Labour under Tony Blair, but during Thatcher's tenure, Labour's opposition remained largely ineffectual in terms of electoral success.

A comparative analysis of Foot and Kinnock's leadership reveals the Labour Party's struggle to adapt to the political realities of the Thatcher era. Foot's principled but rigid approach failed to counter Thatcher's appeal to aspirational voters, while Kinnock's pragmatism, though more electorally savvy, could not overcome the entrenched popularity of Thatcherism. Both leaders faced the challenge of balancing Labour's traditional socialist base with the need to appeal to a broader electorate. Their legacies highlight the complexities of opposition in an era defined by a dominant and transformative political figure.

In practical terms, the Labour Party's opposition during Thatcher's tenure offers lessons for political parties facing ideologically driven governments. First, internal unity is critical; divisions within Labour, exacerbated by the SDP split, weakened its ability to present a coherent alternative. Second, adaptability is essential; while Foot's principles resonated with the party's core, Kinnock's efforts to modernize Labour demonstrated the importance of evolving to meet changing voter expectations. Finally, effective opposition requires not only a critique of the incumbent government but also a compelling vision for the future. Labour's struggle during this period underscores the difficulty of achieving both in the face of a charismatic and policy-driven leader like Thatcher.

Franco's Spain: Political Parties Under His Dictatorship Explained

You may want to see also

Liberal Democrats: Merged party opposing Thatcher's policies on economy, social issues, and governance

The Liberal Democrats, formed in 1988 through the merger of the Liberal Party and the Social Democratic Party (SDP), emerged as a direct response to Margaret Thatcher’s divisive policies. This union was not merely a political realignment but a strategic effort to create a credible alternative to Thatcherism. By combining the Liberals’ centrist traditions with the SDP’s breakaway Labour moderates, the party positioned itself as a counterforce to the Conservative government’s economic, social, and governance agendas. Their opposition was rooted in a rejection of Thatcher’s neoliberal economic policies, her confrontational approach to trade unions, and her socially conservative stance on issues like education, healthcare, and civil liberties.

Economically, the Liberal Democrats championed a mixed economy, advocating for targeted state intervention to balance free-market principles. They opposed Thatcher’s deregulation of financial markets, privatization of state-owned industries, and cuts to public spending, arguing these measures exacerbated inequality and undermined social cohesion. For instance, while Thatcher’s government slashed corporate taxes and reduced welfare spending, the Liberal Democrats proposed progressive taxation and investment in public services to foster inclusive growth. Their 1992 manifesto, for example, called for a 1p increase in income tax to fund education, a policy starkly at odds with Thatcher’s austerity-driven approach.

On social issues, the Liberal Democrats stood as a progressive alternative to Thatcher’s conservatism. They supported LGBT+ rights, racial equality, and gender parity, areas where Thatcher’s government was often seen as regressive. Notably, the party backed the decriminalization of homosexuality and opposed Section 28, the 1988 law banning the "promotion" of homosexuality in schools. Their stance on immigration was similarly inclusive, contrasting Thatcher’s restrictive policies. For practical implementation, the party proposed local initiatives to combat discrimination, such as funding community programs to promote diversity and integration, a direct counter to Thatcher’s centralized, often exclusionary, social policies.

In governance, the Liberal Democrats criticized Thatcher’s centralizing tendencies and advocated for constitutional reform. They pushed for electoral reform, particularly proportional representation, to ensure fairer political representation. This was a direct response to Thatcher’s majoritarian approach, which they argued marginalized minority voices. Additionally, they championed devolution, supporting the creation of regional assemblies and, later, the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly. These proposals aimed to decentralize power, a stark contrast to Thatcher’s concentration of authority in Westminster.

The Liberal Democrats’ opposition to Thatcher was not just ideological but also tactical. By merging, they sought to overcome the "wasted vote" syndrome that had plagued smaller parties under Britain’s first-past-the-post system. Their strategy was to present a unified front, appealing to voters disillusioned with both Thatcher’s Conservatives and Labour’s internal divisions. While their electoral success during Thatcher’s tenure was limited, their role as a vocal opposition laid the groundwork for future influence, particularly in the 2010 coalition government. Their legacy remains in their consistent challenge to Thatcherism, offering a vision of a more equitable, inclusive, and decentralized Britain.

Skinheads and Tea Party Politics: Unmasking Hidden Extremist Agendas

You may want to see also

Trade Unions: Strongly resisted Thatcher's anti-union policies and privatization efforts throughout her leadership

Margaret Thatcher's tenure as Prime Minister was marked by a fierce clash with trade unions, whose resistance to her anti-union policies and privatization agenda became a defining feature of her leadership. The Labour Party, historically aligned with the trade union movement, emerged as the primary political opposition to Thatcher's Conservative government. However, it was the trade unions themselves that formed the backbone of this resistance, mobilizing workers and organizing strikes to challenge her policies.

One of the most notable examples of this resistance was the miners' strike of 1984–1985, led by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). Thatcher's plan to close unprofitable coal mines, part of her broader privatization and deregulation efforts, was met with fierce opposition from miners and their communities. The strike, which lasted nearly a year, became a symbol of the struggle between Thatcher's government and the trade unions. Despite the eventual defeat of the miners, the strike highlighted the resilience and determination of trade unions in the face of Thatcher's policies.

To effectively resist Thatcher's anti-union measures, trade unions employed a variety of strategies. These included mass demonstrations, such as the 1988 "Day of Action" against the poll tax, and legal challenges to government policies. Unions also sought to build alliances with other opposition groups, including community organizations and student movements, to broaden their support base. For instance, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) played a crucial role in coordinating these efforts, providing a platform for unions to share resources and strategies.

A comparative analysis of Thatcher's policies and the union response reveals the ideological divide between her government and the labor movement. While Thatcher championed free-market capitalism and individualism, trade unions advocated for collective bargaining and workers' rights. This fundamental disagreement led to a series of confrontations, with unions viewing Thatcher's policies as an attack on their very existence. The government's use of legislation, such as the Trade Union Act 1984, to restrict union activities further escalated tensions.

In practical terms, trade unions facing similar challenges today can draw valuable lessons from this period. First, unity and solidarity are essential. The ability of unions to mobilize large numbers of workers and maintain support over extended periods was critical to their resistance. Second, diversifying tactics can increase effectiveness. Combining industrial action with legal challenges, public campaigns, and political lobbying can create multiple fronts of resistance. Lastly, building broad-based alliances can amplify the impact of union actions, as seen in the collaboration between unions, community groups, and political parties during the 1980s.

In conclusion, the trade unions' resistance to Margaret Thatcher's anti-union policies and privatization efforts was a multifaceted and determined campaign. Through strikes, legal challenges, and strategic alliances, unions sought to protect workers' rights and challenge the government's agenda. While Thatcher's policies ultimately led to significant changes in British industry and labor relations, the unions' resistance remains a testament to the power of collective action in the face of adversity.

Exploring Egypt's Political Landscape: The Number of Active Parties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$54.99

Scottish National Party (SNP): Opposed Thatcher's policies, particularly their impact on Scotland's economy and culture

The Scottish National Party (SNP) emerged as a staunch opponent of Margaret Thatcher’s policies during her tenure as Prime Minister, particularly due to their devastating impact on Scotland’s economy and cultural fabric. Thatcher’s neoliberal agenda, characterized by deregulation, privatization, and cuts to public spending, clashed sharply with Scotland’s traditionally industrial and socially democratic ethos. The SNP capitalized on widespread Scottish discontent, framing Thatcher’s policies as an assault on Scotland’s identity and livelihoods. This opposition was not merely ideological but deeply rooted in the tangible harm caused by her government’s decisions.

Consider the economic devastation wrought by Thatcher’s policies in Scotland. The decline of heavy industries, such as coal mining and shipbuilding, which were central to Scotland’s economy, led to mass unemployment and the collapse of entire communities. For instance, the closure of pits during the miners’ strike of 1984–1985 left thousands jobless, with regions like Lanarkshire and Fife particularly hard-hit. The SNP argued that these closures were not inevitable but a result of Thatcher’s deliberate policy choices, which prioritized market forces over social welfare. This economic upheaval fueled Scottish resentment and strengthened the SNP’s narrative that Scotland’s interests were being ignored by Westminster.

Culturally, Thatcher’s policies exacerbated a sense of alienation in Scotland. Her government’s emphasis on individualism and free-market capitalism clashed with Scotland’s collective values and its strong tradition of public services. The SNP highlighted how cuts to education, healthcare, and housing disproportionately affected Scotland, further widening the divide between the nations of the UK. For example, the introduction of the poll tax in Scotland a year before the rest of the UK became a symbol of Thatcher’s disregard for Scottish concerns, sparking widespread protests and bolstering the SNP’s argument for greater Scottish autonomy.

To combat these policies, the SNP adopted a dual strategy: opposing Thatcher’s agenda at Westminster while advocating for Scottish self-determination. They positioned themselves as the defenders of Scotland’s economic and cultural interests, a stance that resonated with many Scots. Practical steps included organizing campaigns against specific policies, such as the poll tax, and pushing for devolved powers to protect Scotland’s industries and public services. This period marked a turning point for the SNP, as they transitioned from a fringe party to a significant political force, laying the groundwork for the eventual establishment of the Scottish Parliament in 1999.

In conclusion, the SNP’s opposition to Thatcher’s policies was both a reaction to their harmful effects on Scotland and a strategic move to advance their vision of Scottish self-governance. By focusing on the economic and cultural damage caused by Thatcherism, the SNP not only mobilized Scottish public opinion but also established themselves as a credible alternative to the Conservative government. Their efforts during this era underscore the enduring tension between Scotland and Westminster, a tension that continues to shape Scottish politics today.

Abraham Lincoln's Early Political Roots: His First Party Affiliation

You may want to see also

Left-Wing Activists: Grassroots movements and protests against Thatcher's austerity and conservative social policies

Margaret Thatcher’s tenure as Prime Minister was marked by polarizing policies that galvanized left-wing activists into action. Her austerity measures, privatization of state industries, and conservative social policies sparked widespread resistance. Grassroots movements emerged as a powerful counterforce, organizing protests, strikes, and community campaigns to challenge her agenda. These activists were not confined to a single political party but spanned a spectrum of left-leaning groups, from Labour Party supporters to socialist collectives and trade unions. Their efforts were a testament to the resilience of collective action in the face of systemic change.

One of the most prominent examples of this resistance was the miners’ strike of 1984–1985, a pivotal moment in Thatcher’s Britain. Led by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), the strike was a direct response to her government’s plans to close unprofitable coal mines, which threatened thousands of jobs and entire communities. Left-wing activists mobilized nationwide, organizing solidarity campaigns, food collections, and protests to support the miners. Women Against Pit Closures, a grassroots movement formed by miners’ wives and families, played a crucial role in sustaining the strike through fundraising and raising awareness. Despite the eventual defeat of the strike, it became a symbol of resistance against Thatcher’s neoliberal policies and the human cost of austerity.

Beyond the miners’ strike, left-wing activists targeted Thatcher’s conservative social policies, particularly her Section 28 legislation, which prohibited the "promotion of homosexuality" in schools. LGBTQ+ activists and their allies organized mass protests, such as the 1988 demonstration outside Parliament, to denounce the law as discriminatory. Groups like the Lesbian and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) exemplified the intersectionality of these movements, bridging the fight for workers’ rights with LGBTQ+ rights. Their efforts laid the groundwork for future campaigns against homophobia and highlighted the interconnectedness of social and economic justice.

Grassroots movements also focused on local issues exacerbated by Thatcher’s policies, such as housing and unemployment. In cities like Liverpool, the Militant tendency within the Labour Party led campaigns against cuts to public services and housing, culminating in the city council’s defiance of rate-capping laws. Similarly, the Anti-Poll Tax movement of the late 1980s and early 1990s saw millions of people refuse to pay the controversial tax, leading to mass protests and civil disobedience. These actions demonstrated the power of ordinary people to challenge oppressive policies and forced Thatcher’s government to eventually abandon the tax.

The legacy of these left-wing activists lies in their ability to unite diverse groups under a common cause. Their tactics—from strikes and demonstrations to community organizing and direct action—continue to inspire contemporary movements. While Thatcher’s policies reshaped Britain’s economic and social landscape, the resistance she faced underscores the enduring strength of grassroots activism in fighting austerity and conservatism. Their story is a reminder that even in the face of powerful opposition, collective action can create meaningful change.

1990 Congressional Majority: Which Political Party Held Dominance?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Labour Party was the main political party that opposed Margaret Thatcher and her Conservative Party during her tenure as Prime Minister.

Yes, the Liberal Democrats (and their predecessor, the Liberal Party) opposed Margaret Thatcher's policies, though they were a smaller opposition force compared to the Labour Party.

Yes, smaller parties like the Scottish National Party (SNP), Plaid Cymru (Welsh nationalist party), and various socialist or left-wing groups also opposed Thatcher's policies.

The Labour Party, led by figures like Michael Foot and Neil Kinnock, challenged Thatcher's policies through parliamentary debates, strikes (e.g., the miners' strike), and alternative policy proposals, particularly on issues like privatization and welfare cuts.

While Thatcher's opposition was primarily external, she did face some internal dissent within the Conservative Party, particularly from "wet" Tories who disagreed with her economic and social policies. However, this was not a formal opposition party.