Abraham Lincoln, one of the most revered figures in American history, was nominated for President by the Republican Party in 1860. At a time of deep national division over slavery and states' rights, the Republican Party emerged as a force advocating for the restriction of slavery and the preservation of the Union. Lincoln's nomination reflected the party's commitment to these principles, and his subsequent election as the 16th President of the United States marked a pivotal moment in the nation's history, setting the stage for the Civil War and the eventual abolition of slavery.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Party | Republican Party |

| Year Nominated | 1860 |

| Election Outcome | Won the 1860 Presidential Election |

| Platform Focus | Opposition to the expansion of slavery, emphasis on preserving the Union |

| Key Supporters | Northern states, anti-slavery advocates |

| Opponent Parties | Democratic Party (split into Northern and Southern factions), Constitutional Union Party |

| Inaugural Date | March 4, 1861 |

| Presidency Term | 1861–1865 (assassinated on April 15, 1865) |

| Historical Context | Nominated during a time of deep national division over slavery and states' rights |

Explore related products

$8.95

$8.95

What You'll Learn

- Republican Party's Rise: Lincoln's nomination marked the Republican Party's first presidential victory

- Convention: Lincoln secured the nomination at the Republican National Convention in Chicago

- Platform Focus: The party emphasized anti-slavery expansion and preservation of the Union

- Key Supporters: Eastern Republicans and former Whigs played a crucial role in his nomination

- Opposition Split: Democratic Party division helped Lincoln win with a minority of votes

Republican Party's Rise: Lincoln's nomination marked the Republican Party's first presidential victory

The 1860 presidential election was a watershed moment in American history, not just because it precipitated the secession of Southern states and the Civil War, but because it marked the first presidential victory for the Republican Party. Abraham Lincoln’s nomination and subsequent win were the culmination of a rapid rise for a party that had only been founded six years earlier. Born out of opposition to the expansion of slavery into new territories, the Republicans capitalized on the fracturing of the Whig Party and the growing moral and economic divide over slavery. Lincoln’s nomination was no accident; it was the result of strategic coalition-building, particularly among anti-slavery factions in the North, and a platform that resonated with a nation on the brink of transformation.

To understand the significance of Lincoln’s nomination, consider the political landscape of the 1850s. The Republican Party emerged in 1854 as a response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise and allowed slavery in new territories based on popular sovereignty. This act galvanized anti-slavery activists, who saw the Republicans as the only viable alternative to the Democratic Party, which was increasingly dominated by pro-slavery interests. Lincoln, a former Whig, became a central figure in this new party due to his articulate opposition to slavery’s expansion, as exemplified in his 1858 debates with Stephen A. Douglas. His nomination in 1860 was a testament to the party’s ability to unite diverse factions—from radical abolitionists to moderate conservatives—under a common cause.

The Republican Party’s rise was also fueled by its appeal to Northern economic interests. While slavery was the moral issue that defined the party, its platform also emphasized internal improvements, such as railroads and infrastructure, and support for industrial growth. This dual focus allowed the Republicans to attract both idealistic voters and those motivated by economic self-interest. Lincoln’s nomination reflected this balance; he was a pragmatic leader who could appeal to both the party’s moral core and its practical concerns. His victory in 1860, though he won only 39.8% of the popular vote, demonstrated the effectiveness of this strategy, as the Republican Party secured a majority in the Electoral College by dominating Northern states.

A critical takeaway from Lincoln’s nomination is the importance of timing and context in political movements. The Republican Party’s rise was not inevitable; it was the product of specific historical circumstances, including the collapse of the Second Party System and the intensification of the slavery debate. For modern political strategists, this underscores the need to identify and capitalize on shifting public sentiments and structural opportunities. Just as the Republicans leveraged the moral and economic anxieties of the 1850s, successful political movements today must align their platforms with the pressing issues of their time, whether climate change, economic inequality, or social justice.

Finally, Lincoln’s nomination serves as a reminder of the transformative power of leadership in shaping a party’s identity. His ability to articulate a vision that transcended regional and ideological divides was instrumental in the Republican Party’s success. For contemporary political parties, this highlights the importance of selecting leaders who can unite diverse constituencies and communicate a clear, compelling message. Lincoln’s nomination was not just a victory for him but a validation of the Republican Party’s principles and strategy, setting the stage for its enduring role in American politics.

Strategies to Deconstruct and Dismantle a Political Party Effectively

You may want to see also

1860 Convention: Lincoln secured the nomination at the Republican National Convention in Chicago

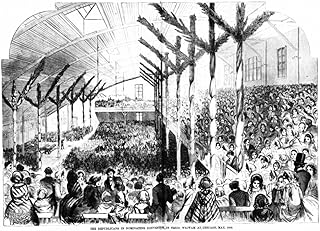

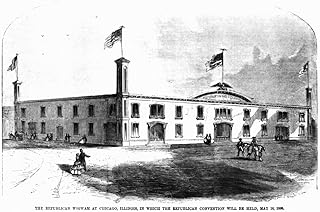

The 1860 Republican National Convention in Chicago was a pivotal moment in American political history, marking the rise of Abraham Lincoln from a relatively unknown Illinois politician to the party’s presidential nominee. Held in the Wigwam, a temporary wooden structure built specifically for the event, the convention drew delegates from across the North, all grappling with the divisive issue of slavery. Lincoln’s nomination was not a foregone conclusion; he faced stiff competition from better-known figures like William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, and Simon Cameron. Yet, through strategic maneuvering and a coalition of Midwestern and Western states, Lincoln emerged victorious on the third ballot, securing the nomination that would ultimately lead him to the presidency.

Lincoln’s success at the convention can be attributed to his carefully cultivated image as a moderate on the slavery issue. While he opposed the expansion of slavery into new territories, he was not an abolitionist, a stance that appealed to both radical and conservative factions within the Republican Party. His team, led by political operative David Davis, worked tirelessly behind the scenes to build support, leveraging Lincoln’s humble background and reputation as a skilled orator. The convention’s dynamics also played in his favor; Seward, the frontrunner, alienated some delegates with his outspoken views, while Lincoln’s quieter, more pragmatic approach resonated with those seeking unity.

The convention itself was a spectacle of 19th-century politics, complete with passionate speeches, backroom deals, and elaborate displays of state pride. Delegates wore badges and carried banners adorned with slogans like “Protection to American Industry” and “Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men.” The atmosphere was electric, reflecting the high stakes of the election in a nation teetering on the brink of secession. Lincoln’s nomination speech, delivered by his friend Norman Judd, emphasized his commitment to preserving the Union and his belief in the economic and moral superiority of free labor over slave labor.

A key takeaway from the 1860 convention is the importance of coalition-building in political success. Lincoln’s campaign understood the need to bridge ideological divides within the Republican Party, focusing on shared goals rather than contentious issues. This strategy not only secured his nomination but also laid the groundwork for his general election victory. For modern political campaigns, the lesson is clear: unity and pragmatism often outweigh ideological purity, especially in polarized times.

Practical tips for understanding this historical event include studying primary sources like delegate diaries and newspaper accounts, which offer insights into the convention’s atmosphere and the delegates’ motivations. Visiting the site of the Wigwam in Chicago, now marked by a plaque, can provide a tangible connection to the past. Additionally, comparing the 1860 convention to modern political conventions highlights how the fundamentals of party politics—coalition-building, messaging, and strategic planning—remain unchanged, even as the tactics evolve.

Understanding Right-Wing Politics: Core Beliefs, Policies, and Global Impact

You may want to see also

Platform Focus: The party emphasized anti-slavery expansion and preservation of the Union

The Republican Party, which nominated Abraham Lincoln for president in 1860, built its platform on two central pillars: preventing the expansion of slavery and preserving the Union. This focus was not merely a moral stance but a strategic response to the deepening divisions between the North and South. By opposing the spread of slavery into new territories, the party aimed to contain the institution’s influence, which it viewed as economically and socially detrimental to the nation’s future. Simultaneously, the commitment to preserving the Union reflected a pragmatic recognition that secession would lead to chaos and undermine the country’s stability.

To understand the party’s emphasis on anti-slavery expansion, consider the political climate of the 1850s. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 had repealed the Missouri Compromise, allowing slavery in territories based on popular sovereignty. This led to violent conflicts, such as "Bleeding Kansas," where pro- and anti-slavery forces clashed. The Republican Party emerged as a direct response to this crisis, advocating for federal policies that would restrict slavery’s growth. For instance, the party supported the Wilmot Proviso, which sought to ban slavery in territories acquired during the Mexican-American War. This stance resonated with Northern voters who feared the economic and moral implications of slavery’s expansion.

Preserving the Union, however, required a delicate balance. While the party was firmly anti-slavery, it did not initially call for the abolition of slavery in existing states. This was a strategic decision to avoid alienating border states and moderate voters. Lincoln himself emphasized in his inaugural address that he had "no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists." This approach aimed to reassure Southern states that their rights would be respected while maintaining a hardline stance against slavery’s expansion. The party’s platform thus reflected a dual focus: containment of slavery and unity of the nation.

Practically, the Republican Party’s platform had significant implications for policy and governance. For example, the party supported the Homestead Act, which provided land to settlers in the West, effectively promoting free labor over slave labor. Additionally, the party’s commitment to internal improvements, such as railroads and infrastructure, aimed to strengthen the national economy and reduce dependence on the South. These measures were not just ideological but also economic, designed to create a nation where free labor and industrial growth could thrive without the moral and economic burden of slavery.

In conclusion, the Republican Party’s emphasis on anti-slavery expansion and preservation of the Union was a carefully crafted strategy to address the nation’s most pressing issues. By focusing on containment rather than immediate abolition, the party sought to appeal to a broad coalition of voters while laying the groundwork for long-term change. This approach ultimately set the stage for Lincoln’s presidency and the transformative policies that would redefine the United States. Understanding this platform provides insight into how political parties can navigate complex moral and practical challenges to shape a nation’s future.

Understanding Third Way Politics: A Middle Ground in Modern Governance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Key Supporters: Eastern Republicans and former Whigs played a crucial role in his nomination

Abraham Lincoln's nomination as the Republican Party's presidential candidate in 1860 was no accident. It hinged on a delicate coalition, with Eastern Republicans and former Whigs serving as its backbone. These groups, though geographically and ideologically diverse, found common ground in Lincoln's moderate stance on slavery and his potential to unite a fractured party.

While Western Republicans championed a more aggressive anti-slavery platform, their Eastern counterparts prioritized preserving the Union and appealing to a broader electorate. They recognized Lincoln's ability to bridge the gap between abolitionists and those seeking a more gradual approach to emancipation. His humble origins and self-made success story resonated with voters, particularly in the crucial swing states of the North.

Former Whigs, still reeling from the collapse of their party, found in Lincoln a familiar figure. His Whig roots and support for internal improvements like railroads and tariffs aligned with their traditional platform. Though the Whig Party had dissolved, its remnants remained a powerful force, and their backing lent Lincoln crucial credibility and organizational support.

The strategic maneuvering of Eastern Republicans and former Whigs was instrumental in securing Lincoln's nomination. They leveraged their influence at the Republican National Convention, skillfully navigating regional tensions and ideological differences. Their efforts ensured Lincoln's victory over more radical candidates, paving the way for his historic presidency.

Understanding the role of these key supporters highlights the intricate political landscape of the 1860s. It demonstrates how Lincoln's nomination was not merely a reflection of his personal qualities, but a testament to the strategic alliances and compromises forged by Eastern Republicans and former Whigs. Their collective efforts shaped the course of American history, setting the stage for Lincoln's leadership during one of the nation's most tumultuous periods.

Changing Political Party Affiliation in Louisiana: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Opposition Split: Democratic Party division helped Lincoln win with a minority of votes

The 1860 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American history, not only for the election of Abraham Lincoln but also for the circumstances that led to his victory. A critical factor was the deep division within the Democratic Party, which ultimately allowed Lincoln to secure the presidency with only 39.8% of the popular vote. This phenomenon, often referred to as the "opposition split," highlights how internal fractures among political opponents can dramatically alter electoral outcomes.

To understand this dynamic, consider the Democratic Party’s inability to unite behind a single candidate. The party was sharply divided over the issue of slavery, with Northern Democrats supporting Stephen A. Douglas and Southern Democrats backing John C. Breckinridge. A third candidate, John Bell, ran under the Constitutional Union Party, further fragmenting the anti-Lincoln vote. This division meant that Lincoln’s opponents collectively garnered a majority of the popular vote, but their inability to coalesce around one candidate handed Lincoln a clear path to victory in the Electoral College.

Analyzing this scenario reveals a strategic lesson: unity among opposition forces is essential to counter a common adversary. The Democrats’ failure to bridge their ideological gaps allowed Lincoln to win despite his minority support. This principle remains relevant in modern politics, where splintered opposition often benefits incumbent or dominant parties. For instance, in multi-party systems, smaller parties with overlapping ideologies may inadvertently weaken their collective influence by competing against each other rather than forming alliances.

Practical takeaways from this historical example include the importance of coalition-building and compromise within political parties. Parties facing internal divisions should prioritize dialogue and consensus-building to avoid self-defeating outcomes. For voters, understanding the mechanics of electoral systems—such as the Electoral College in the U.S.—is crucial, as it underscores how fragmented opposition can lead to unexpected results. Finally, historians and political analysts can use the 1860 election as a case study to illustrate the consequences of party disunity and the strategic advantages of maintaining a unified front.

In conclusion, the Democratic Party’s division in 1860 was a decisive factor in Lincoln’s victory, demonstrating how internal opposition splits can reshape electoral landscapes. This historical event serves as a cautionary tale for modern political parties and a reminder of the enduring impact of strategic unity in achieving political goals.

Matt Damon's Political Party: Uncovering His Affiliation and Views

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Republican Party nominated Abraham Lincoln for president in 1860.

No, Abraham Lincoln ran for president under the Republican Party, not the Whig Party, which had dissolved by the 1850s.

No, John C. Frémont was the first Republican Party presidential nominee in 1856, but Abraham Lincoln was the first Republican to win the presidency in 1860.

While the Republican Party was Lincoln’s primary nominating party, he also received support from the Constitutional Union Party in some border states, though this was not a formal endorsement.