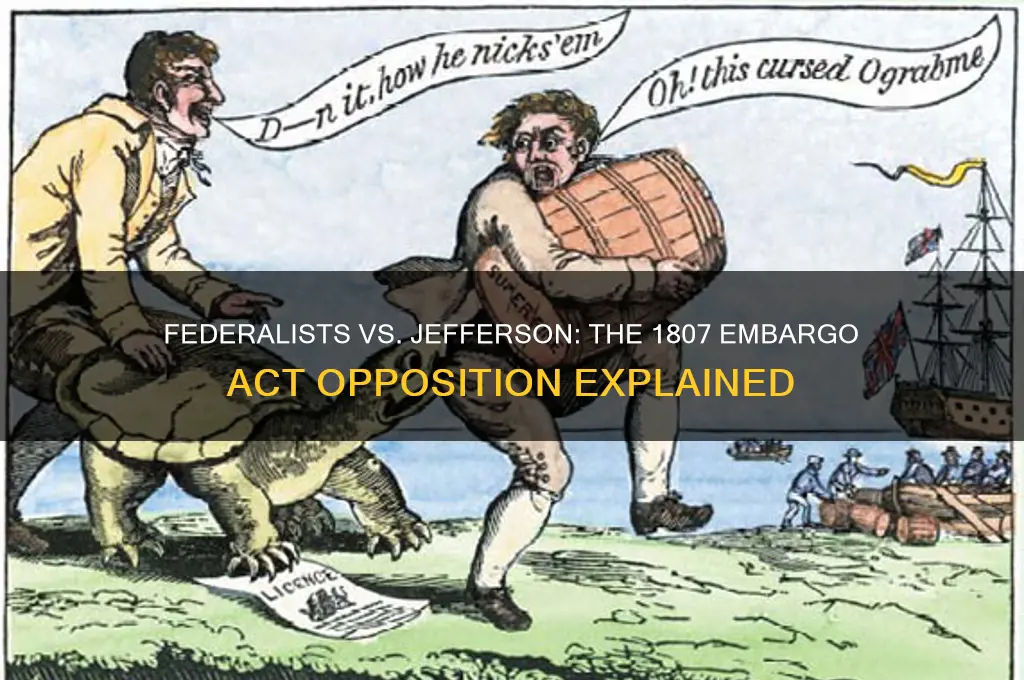

The 1807 Embargo Act, enacted by President Thomas Jefferson, aimed to protect American neutrality and economic interests during the Napoleonic Wars by prohibiting U.S. ships from engaging in foreign trade. While Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party largely supported the measure, it faced staunch opposition from the Federalist Party, which dominated New England. Federalists argued that the embargo devastated the region’s maritime economy, disrupted trade, and unfairly penalized merchants and shipowners. They viewed the policy as a misguided attempt to assert federal authority over states’ rights and economic interests, further deepening the ideological divide between the two parties. The embargo’s unpopularity in Federalist strongholds ultimately fueled widespread resistance and contributed to its eventual repeal in 1809.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Name | Federalist Party |

| Opposition to Embargo | Strongly opposed Jefferson's 1807 Embargo Act |

| Reason for Opposition | Believed it harmed New England's economy and maritime interests |

| Key Figures | Alexander Hamilton, Rufus King, and other Federalist leaders |

| Economic Stance | Supported commerce, trade, and strong ties with Britain |

| Geographic Base | Primarily New England and Mid-Atlantic states |

| Political Ideology | Favored a strong central government and close relations with Britain |

| Impact of Opposition | Contributed to the decline of the Federalist Party's influence |

| Historical Context | Opposed Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans' agrarian and isolationist policies |

| Outcome | Embargo Act was repealed in 1809, replaced by the Non-Intercourse Act |

| Legacy | Highlighted regional economic divisions in early 19th-century America |

Explore related products

$17.99 $17.99

What You'll Learn

- Federalist Party's Strong Opposition: Federalists led resistance, calling embargo economically disastrous and unconstitutional

- New England's Defiance: New England states openly defied embargo, smuggling goods to protect trade interests

- Western Farmers' Support: Western farmers initially backed embargo, hoping to boost domestic markets

- Smuggling and Enforcement: Widespread smuggling undermined embargo, exposing weak federal enforcement capabilities

- Political Backlash: Embargo's failure fueled Federalist resurgence, weakening Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party

Federalist Party's Strong Opposition: Federalists led resistance, calling embargo economically disastrous and unconstitutional

The Federalist Party emerged as the staunchest critic of Thomas Jefferson’s 1807 Embargo Act, a policy designed to assert American neutrality during the Napoleonic Wars by halting all foreign trade. Federalists, rooted in New England’s mercantile economy, viewed the embargo as a direct assault on their region’s prosperity. Their opposition was twofold: economic and constitutional. They argued that the embargo would cripple trade-dependent industries, particularly shipbuilding and textiles, while also violating states’ rights and individual liberties. This resistance was not merely ideological but deeply practical, as Federalists saw the embargo as a threat to their political and economic survival.

Economically, the embargo’s impact was immediate and devastating, particularly in Federalist strongholds. New England ports, once bustling hubs of international commerce, fell silent as ships were idled and warehouses emptied. Federalists pointed to skyrocketing unemployment and bankruptcies as evidence of the policy’s folly. For instance, in Massachusetts, the value of exports plummeted from $13 million in 1807 to a mere $1 million by 1808. Smuggling became rampant, further undermining the embargo’s effectiveness and highlighting its impracticality. Federalists seized on these outcomes to portray Jefferson’s administration as out of touch with the realities of the American economy.

Constitutionally, Federalists argued that the embargo overstepped federal authority. They contended that the Constitution did not grant Congress the power to halt all foreign trade unilaterally, viewing it as an infringement on states’ rights and individual freedoms. This critique resonated with their broader skepticism of Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican policies, which they saw as dangerously expansive. By framing the embargo as unconstitutional, Federalists sought to rally public opinion against what they perceived as federal overreach, positioning themselves as defenders of limited government and regional autonomy.

The Federalist opposition was not merely reactive but strategic. They leveraged their control of local governments and media outlets to amplify their message, organizing protests and publishing pamphlets that lambasted the embargo. In states like Connecticut and Rhode Island, Federalist-dominated legislatures passed resolutions denouncing the policy and even threatened secession. This coordinated resistance underscored the depth of their opposition and their willingness to challenge the federal government’s authority. Their efforts, while ultimately unsuccessful in overturning the embargo, laid the groundwork for future debates over federal power and states’ rights.

In retrospect, the Federalist Party’s opposition to the 1807 Embargo Act was a defining moment in early American politics. Their critique exposed the policy’s economic and constitutional flaws, forcing a national conversation about the limits of federal authority and the balance between national interests and regional economies. While the embargo was repealed in 1809, the Federalists’ resistance left a lasting legacy, shaping subsequent debates over trade, neutrality, and the role of government. Their stance, though rooted in self-interest, highlighted the complexities of governing a diverse and economically disparate nation.

James Monroe's Political Party: Uncovering the Democratic-Republican Affiliation

You may want to see also

New England's Defiance: New England states openly defied embargo, smuggling goods to protect trade interests

The Federalists, a political party dominant in New England, staunchly opposed Thomas Jefferson’s 1807 Embargo Act, viewing it as a direct assault on their region’s economic lifeline. While the embargo aimed to assert American neutrality by halting trade with Britain and France, it disproportionately crippled New England’s maritime-dependent economy. Federalist leaders, such as Timothy Pickering, openly condemned the policy, arguing it favored Southern agrarian interests at the expense of Northern commerce. This ideological clash set the stage for New England’s defiance, as states like Massachusetts and Connecticut refused to enforce the embargo, prioritizing local survival over federal authority.

Smuggling became the lifeblood of New England’s resistance, with merchants and coastal communities orchestrating clandestine trade networks to bypass the embargo. Ships laden with goods slipped under the cover of night to Canadian ports or directly to British markets, often with the tacit approval of local officials. The sheer scale of defiance underscored the embargo’s impracticality; by 1808, over 1,000 vessels had been seized for violations, yet smuggling persisted. This cat-and-mouse game between federal agents and New England traders highlighted the region’s determination to protect its economic interests, even at the risk of legal repercussions.

The embargo’s economic toll on New England was devastating, with unemployment soaring and ports like Boston and Salem falling silent. Shipyards lay dormant, and warehouses gathered dust as trade ground to a halt. Desperate families turned to smuggling not out of malice but necessity, as the embargo threatened their very livelihoods. This grassroots resistance was not merely an act of rebellion but a survival strategy, illustrating the human cost of policies disconnected from regional realities. The embargo’s failure to account for New England’s unique economic structure fueled widespread discontent, further entrenching Federalist opposition.

New England’s defiance also exposed the limits of federal power in the early Republic. State legislatures passed resolutions denouncing the embargo, and local militias occasionally intervened to protect smugglers from federal authorities. This open challenge to Jefferson’s administration foreshadowed deeper questions about states’ rights and the balance of power between the federal government and individual states. The embargo crisis became a turning point, galvanizing Federalist calls for a more decentralized approach to governance and laying the groundwork for future sectional conflicts.

In retrospect, New England’s defiance of the 1807 Embargo Act was both a practical response to economic hardship and a political statement against perceived Southern dominance. The episode serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of one-size-fits-all policies in a diverse nation. For modern policymakers, it underscores the importance of considering regional economic disparities and fostering inclusive dialogue to avoid alienating critical constituencies. New England’s resistance, though ultimately futile in overturning the embargo, remains a powerful reminder of the resilience of communities in the face of adversity and the enduring tension between federal authority and local autonomy.

Unveiling Sam's Political Affiliation: Which Party Does Sam Support?

You may want to see also

Western Farmers' Support: Western farmers initially backed embargo, hoping to boost domestic markets

Western farmers, a pivotal demographic in early 19th-century America, initially threw their weight behind Jefferson’s 1807 Embargo Act, driven by the promise of strengthened domestic markets. At the time, these farmers were heavily reliant on foreign trade, particularly with Britain and France, to sell their surplus crops like wheat, corn, and tobacco. The embargo, which prohibited American ships from sailing to foreign ports, was seen as a way to force European powers to respect American neutrality and, in turn, redirect economic activity inward. For farmers in the West, this meant a potential surge in demand for their goods from Eastern cities and other domestic regions, offering a lucrative alternative to volatile international markets.

However, this support was not rooted in ideological alignment with Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party but rather in pragmatic economic self-interest. Western farmers had long felt marginalized by federal policies that favored Eastern commercial and shipping interests. The embargo, they hoped, would level the playing field by curtailing the dominance of coastal merchants and shifting economic power westward. This optimism was further fueled by the belief that domestic industries, including agriculture, would flourish as consumers turned to homegrown products in the absence of foreign imports.

Yet, the reality of the embargo quickly exposed the flaws in this reasoning. Within months, the lack of foreign trade led to a collapse in commodity prices, as domestic markets were unable to absorb the surplus crops. Farmers, who had anticipated higher profits, instead faced mounting debts and unsold inventories. The embargo’s unintended consequences—economic stagnation, unemployment, and widespread smuggling—eroded the initial enthusiasm of Western farmers, turning their support into resentment.

This shift in sentiment highlights the delicate balance between policy intentions and practical outcomes. While the embargo aimed to assert American sovereignty, it failed to account for the interconnectedness of the early American economy. Western farmers, initially drawn by the promise of domestic market growth, became some of the embargo’s most vocal critics, illustrating the complexities of aligning political goals with local economic realities. Their experience serves as a cautionary tale about the risks of policies that disrupt established trade networks without offering viable alternatives.

In retrospect, the initial support of Western farmers for the embargo underscores the importance of inclusive policy-making. Had Jefferson’s administration more thoroughly consulted agricultural interests or implemented measures to bolster domestic demand, the embargo might have achieved its intended goals without alienating a key constituency. Instead, the embargo’s failure contributed to the rise of opposition parties, particularly the Federalists, who capitalized on the economic distress to challenge Democratic-Republican dominance. For modern policymakers, this episode offers a clear lesson: economic policies must consider the diverse needs of all sectors, not just those of dominant industries, to avoid unintended consequences and maintain public support.

Understanding Political Primaries: Key Dates and What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Smuggling and Enforcement: Widespread smuggling undermined embargo, exposing weak federal enforcement capabilities

The Embargo Act of 1807, signed by President Thomas Jefferson, aimed to protect American interests by halting all foreign trade. However, it inadvertently spawned a shadow economy of smuggling that highlighted the federal government’s limited enforcement power. Coastal towns from New England to the South became hubs for clandestine trade, as merchants and citizens alike defied the embargo to sustain their livelihoods. This widespread defiance not only undermined the act’s purpose but also exposed the federal government’s inability to police its own borders effectively.

Consider the mechanics of smuggling during this era: small, fast vessels known as "Baltimore clippers" were favored for their speed and agility, outmaneuvering the slower federal revenue cutters tasked with enforcement. Smugglers often operated under the cover of night, using hidden coves and unmarked routes to evade detection. In some cases, entire communities colluded to protect smugglers, further complicating federal efforts. For instance, in ports like Boston and Charleston, local officials turned a blind eye to illegal trade, prioritizing economic survival over federal law. This local resistance underscored the disconnect between Jefferson’s idealistic policy and the practical realities of enforcement.

The Federalist Party, Jefferson’s chief political opponents, capitalized on this enforcement failure to criticize the embargo. They argued that the act not only crippled the economy but also demonstrated the federal government’s overreach and incompetence. Smuggling became a symbol of the embargo’s futility, as even Jefferson’s own supporters began to question the wisdom of a policy that could not be enforced. The Federalist-controlled press published stories of smuggling successes, portraying them as acts of defiance against an oppressive government. This narrative resonated with a public already suffering from the embargo’s economic consequences.

To understand the scale of the problem, consider the numbers: by 1808, it was estimated that thousands of smuggling voyages had taken place, with goods ranging from cotton and tobacco to luxury items like wine and silk. The federal government’s response was often reactive and ineffective. Revenue cutters were undermanned and poorly equipped, while penalties for smuggling were inconsistently enforced. In one notable case, a smuggler caught with a cargo of illegal goods in New York was fined a mere fraction of the shipment’s value, illustrating the weak deterrent effect of federal law.

The takeaway is clear: the embargo’s failure to curb smuggling revealed systemic weaknesses in federal authority. It was not just a policy misstep but a lesson in the limits of governmental power in the face of economic necessity and local resistance. The Federalist Party’s opposition gained traction as they framed the embargo as a symbol of Jeffersonian overreach, setting the stage for their political resurgence in the years to come. Smuggling, once a clandestine act, became a political tool, exposing the fragility of federal enforcement and the resilience of those who defied it.

Understanding Socio-Political Discourse: Power, Language, and Social Change Explained

You may want to see also

Political Backlash: Embargo's failure fueled Federalist resurgence, weakening Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party

The Embargo Act of 1807, a cornerstone of Thomas Jefferson’s foreign policy, aimed to assert American neutrality and economic independence during the Napoleonic Wars. By halting all U.S. exports, Jefferson sought to pressure Britain and France into respecting American sovereignty. However, the embargo’s unintended consequences—economic devastation, widespread smuggling, and public discontent—created fertile ground for political backlash. Chief among the critics were the Federalists, who seized the opportunity to reassert their influence, capitalizing on the embargo’s failures to weaken Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party.

Consider the embargo’s immediate impact on New England, a Federalist stronghold. The region’s economy, heavily reliant on maritime trade, was crippled. Shipyards lay dormant, merchants faced bankruptcy, and workers lost their livelihoods. Federalists framed the embargo as a Southern-driven policy that disregarded Northern interests, a narrative that resonated deeply with their base. By contrasting Jefferson’s idealism with the harsh realities faced by ordinary citizens, Federalists positioned themselves as pragmatic defenders of regional and economic stability.

The embargo’s failure also exposed vulnerabilities within the Democratic-Republican Party. Jefferson’s insistence on strict enforcement alienated moderates, while the policy’s ineffectiveness undermined his administration’s credibility. Federalists exploited these divisions, portraying the embargo as a symbol of Democratic-Republican mismanagement. Their resurgence was not merely a reaction to economic hardship but a strategic campaign to reclaim political legitimacy after years of decline. By 1808, Federalist candidates began winning local and state elections, signaling a shift in public sentiment.

A comparative analysis of the embargo’s aftermath reveals its role as a turning point in early American politics. While Jefferson intended to strengthen the nation through economic self-reliance, the policy instead fractured domestic unity and emboldened opposition. The Federalists’ resurgence was not just a backlash against the embargo but a broader rejection of Jeffersonian ideology. Their critique of centralized power and advocacy for regional autonomy struck a chord with voters disillusioned by the embargo’s failures.

Practical lessons from this episode underscore the risks of unilateral policies in a diverse nation. For modern policymakers, the embargo serves as a cautionary tale: economic measures must account for regional disparities and public tolerance. To avoid similar backlashes, leaders should prioritize inclusive decision-making and transparent communication. For historians and political analysts, the embargo’s legacy highlights the interplay between policy, public opinion, and partisan dynamics—a reminder that even well-intentioned actions can have unintended political consequences.

Exploring France's Political Landscape: Key Parties and Their Influence

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Federalist Party strongly opposed Jefferson's 1807 Embargo Act.

The Federalists opposed the Embargo Act because it severely damaged New England's economy, which relied heavily on maritime trade, and they viewed it as an overreach of federal power.

The Federalists resisted the Embargo Act by smuggling goods, openly criticizing the policy, and advocating for states' rights to nullify federal laws they deemed unconstitutional.

Yes, the Federalist Party gained significant support, particularly in New England, as the Embargo Act's economic hardships fueled public discontent with Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party.

The opposition to the Embargo Act temporarily revived Federalist influence, but their association with anti-embargo sentiment and perceived disloyalty during the War of 1812 ultimately contributed to the party's decline.