The Democratic Party, particularly in the Southern United States, historically opposed Black voting rights during the Reconstruction era and well into the 20th century. Following the Civil War, as African Americans gained the right to vote through the 15th Amendment, Southern Democrats fiercely resisted this change by implementing discriminatory measures such as poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses to disenfranchise Black voters. Additionally, the party supported Jim Crow laws and used violence and intimidation through groups like the Ku Klux Klan to suppress Black political participation. This opposition persisted until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which was met with resistance from many Southern Democrats, while national Democrats increasingly championed civil rights.

Explore related products

$18.99 $25.95

What You'll Learn

Southern Democrats' Resistance to Black Suffrage

The Democratic Party in the post-Civil War South emerged as a formidable force against Black suffrage, employing a combination of legal, political, and extralegal tactics to suppress African American voting rights. This resistance was rooted in the party’s commitment to maintaining white supremacy and the economic structures of the former Confederacy. While the 15th Amendment (1870) nominally granted Black men the right to vote, Southern Democrats systematically undermined its enforcement through poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses. These measures, often disguised as neutral reforms, were explicitly designed to disenfranchise Black voters while preserving the political power of white Democrats.

Consider the Mississippi Plan of 1890, a blueprint for disenfranchisement adopted by other Southern states. Democrats in Mississippi convened a constitutional convention to rewrite the state’s governing document, embedding provisions that required poll taxes, literacy tests, and a vague "understanding" clause that allowed white registrars to arbitrarily deny Black voters. The plan’s architects openly admitted its purpose: to "eliminate the nigger from politics." By 1896, Black voter turnout in Mississippi had plummeted from 70% to less than 10%, effectively restoring one-party Democratic rule. This model was replicated across the South, ensuring that Black political participation remained negligible until the mid-20th century.

The resistance to Black suffrage was not merely legal but also violent and extralegal. Southern Democrats often colluded with paramilitary groups like the Ku Klux Klan and White League to intimidate Black voters through lynchings, beatings, and economic coercion. For instance, in the 1876 presidential election, South Carolina Democrats used violence to suppress Black voting, helping to secure the state for Rutherford B. Hayes in a contested election. This pattern of violence was a deliberate strategy to enforce white dominance and deter Black political engagement. The federal government’s eventual withdrawal of Reconstruction troops in 1877 left Black voters vulnerable, allowing Southern Democrats to consolidate their control.

Analytically, the Southern Democrats’ resistance to Black suffrage reveals a calculated effort to preserve racial hierarchy and economic exploitation. By disenfranchising Black voters, Democrats ensured that policies favoring white landowners and industrialists remained unchallenged. This suppression also prevented Black political leaders from addressing issues like sharecropping, wage inequality, and access to education. The legacy of this resistance is evident in the enduring racial disparities in political representation and socioeconomic outcomes across the South. Understanding this history is crucial for addressing contemporary voter suppression efforts, which often echo the tactics of the post-Reconstruction era.

Practically, the fight against Southern Democratic resistance offers lessons for modern voting rights advocates. First, legal reforms must be paired with robust enforcement mechanisms to prevent circumvention. Second, grassroots organizing and voter education are essential to counteracting intimidation and misinformation. Finally, federal oversight remains critical in states with a history of disenfranchisement. By studying the strategies of the past, activists can develop more effective responses to protect the right to vote for all citizens, regardless of race.

Understanding Political Parties: Their Vital Roles in Shaping Governance and Society

You may want to see also

Jim Crow Laws Suppressing Black Voters

The Jim Crow laws, enacted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, were a systematic effort by Southern states to disenfranchise Black voters and maintain white supremacy. These laws, often associated with the Democratic Party in the South, employed a variety of tactics to suppress Black political participation, including poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses. For instance, a poll tax required voters to pay a fee before casting their ballot, a significant burden for impoverished Black communities. This financial barrier was just one of many tools designed to exclude Black citizens from the democratic process.

Consider the literacy test, a seemingly neutral requirement that voters demonstrate the ability to read and write. In practice, these tests were administered in a discriminatory manner, with Black voters often facing more challenging questions or arbitrary failures. A 1965 report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that in Alabama, 63% of Black applicants failed the literacy test, compared to only 8% of white applicants. This disparity highlights the intentionality behind these measures, which were not about ensuring voter competence but about preserving racial hierarchy.

One of the most insidious aspects of Jim Crow laws was the grandfather clause, which exempted individuals from literacy tests or poll taxes if their grandfathers had been eligible to vote before 1867. This provision effectively excluded Black citizens, whose ancestors had been enslaved and thus ineligible to vote, while allowing poor and illiterate whites to maintain their voting rights. This clause exemplifies the legal ingenuity employed to codify racial inequality, ensuring that political power remained in the hands of whites.

To combat these suppressive measures, civil rights activists and organizations like the NAACP launched legal challenges and voter registration drives. The passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed discriminatory voting practices, marked a significant victory. However, the legacy of Jim Crow laws persists in modern voter suppression efforts, such as strict voter ID laws and reductions in polling places in minority communities. Understanding this history is crucial for recognizing contemporary barriers to voting and advocating for equitable access to the ballot box.

In practical terms, individuals can contribute to the fight against voter suppression by supporting organizations that promote voter education and registration, particularly in underserved communities. Volunteering as a poll worker or assisting with transportation to polling sites can also make a tangible difference. By learning from the past and taking proactive steps, we can work toward a more inclusive democracy that upholds the rights of all citizens, regardless of race.

Political Parties as Participatory Vehicles: Engaging Citizens in Democracy

You may want to see also

Poll Taxes and Literacy Tests

Consider the mechanics of literacy tests: they were not standardized assessments of reading ability but rather instruments of discrimination. A white applicant might be asked to name the county sheriff, while a Black applicant would be quizzed on the number of bubbles in a bar of soap. In Alabama, one test required voters to copy a section of the state constitution, a task made deliberately difficult by the document’s dense language. These tests were designed to fail Black voters, regardless of their actual literacy. For instance, in Mississippi, where 60% of Black adults were literate by 1940, only 3% were registered to vote due to such barriers.

The poll tax, though seemingly neutral, targeted Black voters with surgical precision. In Texas, for example, the $1.50 tax (approximately $27 today) was due six months before an election, a timeline that disproportionately affected sharecroppers and tenant farmers who lacked steady income. Exemptions were granted to the "sons of Confederate veterans," a loophole that overwhelmingly benefited white voters. By 1960, only five states still enforced poll taxes, but their impact was profound: in Alabama, Black voter registration hovered around 10% despite constituting nearly half the population.

The fight against these measures was long and arduous. The 24th Amendment, ratified in 1964, outlawed poll taxes in federal elections, but it took the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to dismantle literacy tests and other discriminatory practices. Even then, resistance persisted. In Selma, Alabama, local officials continued to administer literacy tests until federal examiners intervened. The legacy of these tactics endures today in voter ID laws and other restrictions that disproportionately affect minority communities, underscoring the enduring struggle for equitable access to the ballot.

To understand the full scope of these tools, consider their intersection with other Jim Crow laws. Poll taxes and literacy tests were part of a broader system that included grandfather clauses, which exempted voters whose ancestors had voted before 1867 (effectively excluding Blacks), and all-white primaries. These measures were not isolated policies but components of a coordinated effort to maintain white supremacy. By studying them, we gain insight into the calculated nature of voter suppression and the resilience of those who fought against it. Practical steps to combat modern-day equivalents include advocating for automatic voter registration, challenging restrictive ID laws, and supporting organizations like the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

Unveiling Political Fundraising: Strategies, Sources, and Campaign Finance Secrets

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Intimidation Tactics by White Supremacist Groups

White supremacist groups have historically employed intimidation tactics to suppress Black voting, often aligning with or influencing political parties that opposed racial equality. One of the most notorious examples is the Democratic Party in the post-Reconstruction South, which, through its conservative wing, enforced Jim Crow laws and supported groups like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). These groups used violence, threats, and psychological terror to deter Black Americans from exercising their constitutional right to vote. Lynchings, cross burnings, and physical assaults were common methods, creating an atmosphere of fear that persisted for decades.

Analyzing these tactics reveals a calculated strategy to maintain white political dominance. For instance, the KKK’s resurgence in the early 20th century coincided with the rise of segregationist policies, such as poll taxes and literacy tests, which were legally enforced by Southern Democrats. White supremacist groups complemented these legal barriers with extralegal violence, targeting not only individuals but also their families and communities. This dual approach ensured that even those who overcame legal hurdles faced life-threatening consequences for attempting to vote. The message was clear: defiance would be met with brutal retaliation.

To understand the effectiveness of these tactics, consider the statistics. In Mississippi, for example, Black voter registration dropped from over 67% during Reconstruction to less than 6% by 1940. This dramatic decline was not accidental but a direct result of coordinated intimidation efforts. White supremacist groups often acted with impunity, as local law enforcement and political leaders either supported their actions or turned a blind eye. This collusion between extremist groups and political institutions highlights how intimidation was systemic, not isolated.

Practical resistance to these tactics emerged through grassroots organizing and legal challenges. Civil rights groups like the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) documented violence, provided legal aid, and mobilized communities to demand federal intervention. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed discriminatory voting practices, was a direct response to these efforts. However, even after its passage, white supremacist groups adapted their tactics, shifting from overt violence to more subtle forms of intimidation, such as voter suppression campaigns and disinformation.

Today, the legacy of these intimidation tactics persists in modern voter suppression efforts. While explicit violence has decreased, white supremacist groups continue to influence political discourse and policy, often under the guise of "election integrity." Understanding this history is crucial for combating contemporary challenges to voting rights. By recognizing the patterns and strategies of the past, activists and policymakers can develop targeted responses to ensure that the right to vote remains protected for all Americans.

When Music Becomes a Political Statement: Exploring the Intersection

You may want to see also

Republican vs. Democrat Stances on Voting Rights

The historical record shows that the Democratic Party, particularly in the South, was the primary opponent of Black voting rights during the 19th and early 20th centuries. This opposition was rooted in the party’s alignment with Confederate ideals and Jim Crow laws, which systematically disenfranchised African Americans through poll taxes, literacy tests, and violence. The Republican Party, on the other hand, championed Black suffrage during Reconstruction, leading to the passage of the 15th Amendment in 1870, which prohibited racial discrimination in voting. This stark contrast in historical stances sets the stage for understanding contemporary debates on voting rights.

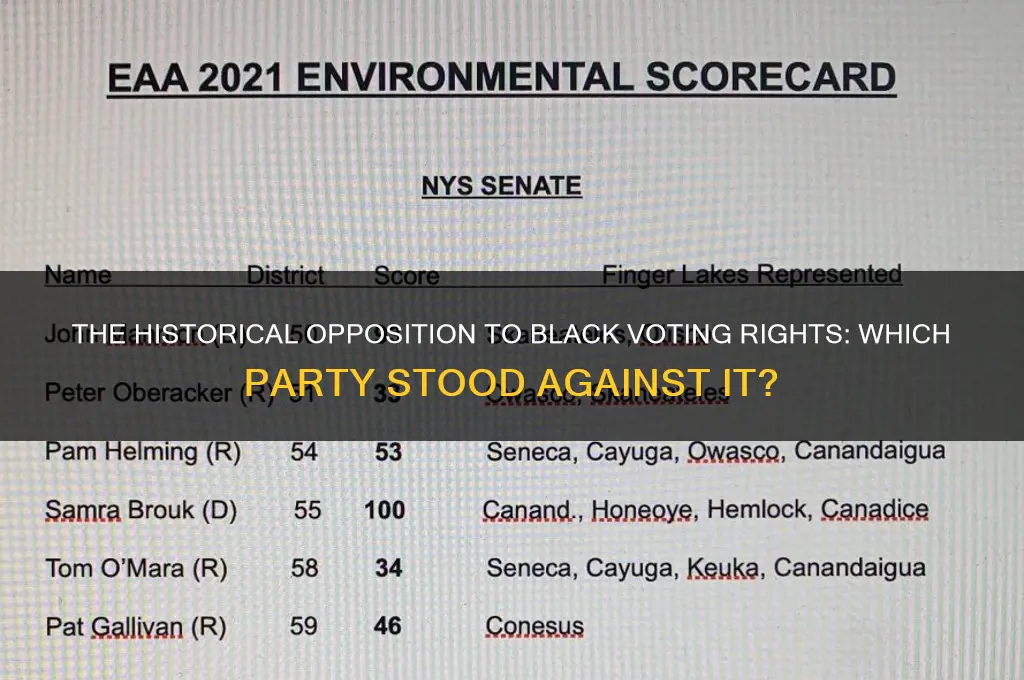

Fast forward to the 21st century, and the roles have shifted, though the underlying tensions remain. Today, Republicans often argue for stricter voter ID laws and reduced early voting periods, framing these measures as necessary to prevent fraud. Democrats counter that such policies disproportionately affect minority voters, who are less likely to possess government-issued IDs or have flexible schedules for in-person voting. For instance, a 2021 Brennan Center study found that Black voters are 39% more likely than white voters to lack the IDs required by new state laws. This data underscores the partisan divide: Republicans emphasize election integrity, while Democrats prioritize accessibility.

To navigate this divide, consider the practical implications of these stances. If you’re a voter in a state with new ID requirements, ensure you have the necessary documentation well before Election Day. Organizations like the NAACP and ACLU offer resources to help voters understand their rights and overcome barriers. For advocates, focus on evidence-based arguments: studies consistently show that voter fraud is exceedingly rare, with one analysis finding only 31 credible cases out of over 1 billion ballots cast between 2000 and 2014. This data can counter claims that restrictive measures are needed to protect elections.

Comparatively, the Democratic Party’s current platform pushes for automatic voter registration, restoration of voting rights for felons, and expansion of mail-in voting—policies aimed at increasing turnout among marginalized groups. Republicans, meanwhile, have supported measures like purging voter rolls and limiting ballot drop boxes, often in states with significant minority populations. For example, Georgia’s 2021 voting law reduced the number of drop boxes in Fulton County, home to a large Black population, by 75%. Such actions highlight the ongoing struggle over who gets to participate in democracy.

In conclusion, while the parties’ positions on voting rights have evolved since the Civil Rights era, the core debate remains: accessibility versus integrity. Voters and advocates must stay informed, engage in local and national discussions, and push for policies that balance security with inclusivity. History reminds us that the right to vote is a cornerstone of democracy, and its protection requires vigilance from all sides.

John Bel Edwards' Political Affiliation: Unraveling His Party Ties

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party was the primary political party that historically opposed Black voting rights, particularly during the Reconstruction era and the Jim Crow period.

The Democratic Party supported and enforced measures like poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses, as well as violent intimidation tactics by groups like the Ku Klux Klan, to suppress Black voting.

No, the Republican Party was the primary advocate for Black voting rights, passing the 15th Amendment and other legislation to protect Black suffrage, while the Democratic Party consistently opposed these efforts.