The opposition to women's suffrage in the United States was notably led by the Anti-Suffrage Movement, which, while not a formal political party, was closely aligned with conservative factions within both the Democratic and Republican parties. Among these, the Democratic Party often played a significant role in resisting suffrage efforts, particularly in the South, where traditional gender roles and racial anxieties influenced their stance. Southern Democrats feared that extending the vote to women, especially white women, might disrupt the social order and potentially align with progressive reforms they opposed. Additionally, some conservative Republicans and members of smaller parties, such as the Constitution Party, also voiced opposition, arguing that suffrage would undermine family structures or lead to radical political changes. However, it is essential to note that opposition was not uniform across parties, and many individual politicians and factions within these parties supported women’s suffrage.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Anti-Suffrage Arguments: Fear of disrupting traditional gender roles and societal norms

- Key Opponents: Notable figures like Josephine Jewell Dodge and Massachusetts leaders

- Anti-Suffrage Organizations: National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage and state-level groups

- Tactics Used: Propaganda, petitions, and lobbying to block suffrage legislation

- Political Parties: Conservative factions within Republican and Democratic parties resisted women's voting rights

Anti-Suffrage Arguments: Fear of disrupting traditional gender roles and societal norms

The anti-suffrage movement often hinged on the fear that women's voting rights would upend traditional gender roles, a cornerstone of societal stability in their view. This argument was particularly potent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when domesticity and separate spheres for men and women were deeply ingrained cultural norms. Anti-suffragists warned that granting women the vote would blur the lines between public and private life, leading to a breakdown of the family structure. They believed that women's primary role as caregivers and homemakers would be compromised if they ventured into the male-dominated realm of politics.

Consider the rhetoric of the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women, which argued that suffrage would "distract women from their natural duties." This organization, like many others, portrayed suffrage as a threat to the sanctity of the home, suggesting that politically active women would neglect their families. They often invoked the image of the "ideal woman"—devoted, nurturing, and apolitical—as a counterpoint to the suffragist, who was depicted as aggressive, unfeminine, and a danger to societal harmony.

To understand the depth of this fear, examine the historical context. In an era where women's education was often limited to domestic skills and moral training, the idea of women engaging in political discourse was seen as radical. Anti-suffragists capitalized on this unease, framing suffrage as a step toward gender ambiguity and moral decay. They warned that if women entered the public sphere, men would lose their sense of purpose as providers and protectors, leading to a societal imbalance.

Practical concerns were also woven into this narrative. Anti-suffragists argued that women lacked the necessary experience and knowledge to vote wisely, as their lives were sheltered from the harsh realities of politics and economics. They claimed that women's suffrage would result in emotional, rather than rational, decision-making, further destabilizing governance. This argument was often accompanied by patronizing advice, such as encouraging women to focus on "influencing men" through their domestic roles rather than seeking political power directly.

In retrospect, the fear of disrupting traditional gender roles was a powerful tool for anti-suffragists, tapping into deeply held cultural beliefs. However, it also reveals the fragility of these norms, which were ultimately unable to withstand the push for equality. Today, this argument serves as a reminder of how societal fears can be manipulated to resist progress, but also how such resistance is often rooted in outdated and restrictive ideals. Understanding this dynamic can help modern advocates navigate contemporary debates about gender roles and equality.

Will Rogers: Humor, Politics, and a Legacy of Witty Wisdom

You may want to see also

Key Opponents: Notable figures like Josephine Jewell Dodge and Massachusetts leaders

The anti-suffrage movement in the United States was not merely a faceless opposition but a structured campaign led by influential figures who wielded considerable social and political power. Among these, Josephine Jewell Dodge stands out as a pivotal figure whose efforts were both strategic and deeply rooted in her beliefs. Dodge, a prominent socialite and educator, founded the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS) in 1911, which became a formidable force against the suffrage movement. Her argument hinged on the notion that women’s roles in the home and community were inherently more valuable than political participation, a stance that resonated with many conservative women of her time. Dodge’s organization distributed literature, held public meetings, and lobbied politicians, effectively amplifying the anti-suffrage voice on a national scale.

In Massachusetts, the anti-suffrage movement found some of its most vocal and organized leaders. The Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women (MAOFESW) was a powerhouse of opposition, led by figures like Alice Stone Blackwell, who paradoxically was the daughter of a prominent suffragist. These leaders leveraged their social standing and networks to argue that women’s suffrage would disrupt traditional family structures and dilute the political process. Their tactics included public debates, where they often framed suffrage as a threat to women’s dignity and societal order. For instance, they claimed that voting would expose women to the corrupting influences of politics, a message that appealed to conservative sentiments.

One of the most intriguing aspects of these opponents was their ability to frame their resistance as a form of protection for women. They argued that women were already influential through their roles as mothers, educators, and community leaders, and that political involvement would diminish their unique contributions. This narrative was particularly effective in swaying undecided women, who might have feared the unknown consequences of suffrage. Dodge and her Massachusetts counterparts mastered the art of persuasive communication, often using emotional appeals rather than purely logical arguments to make their case.

To understand their impact, consider the practical steps they took to organize their movement. Dodge’s NAOWS published *The Woman’s Protest Against Woman Suffrage*, a widely circulated pamphlet that outlined their arguments in a concise, accessible format. Similarly, Massachusetts leaders hosted tea parties and parlor meetings, spaces traditionally associated with women, to discuss their views in a familiar setting. These methods were deliberate, designed to engage women on their own terms and within their comfort zones. For those studying opposition movements, this approach offers a lesson in tailoring messaging to the audience’s cultural and social norms.

In conclusion, the anti-suffrage movement’s key opponents were not just ideologues but skilled organizers and communicators. Josephine Jewell Dodge and Massachusetts leaders like those in MAOFESW left a legacy of strategic resistance, demonstrating how deeply held beliefs can be transformed into effective political campaigns. Their efforts, while ultimately unsuccessful, provide a fascinating study in the dynamics of opposition and the complexities of social change. Understanding their tactics and arguments offers valuable insights into the challenges faced by reform movements and the enduring power of traditional narratives.

Will Ferrell's Political Satire: A Hilarious Take on Modern Politics

You may want to see also

Anti-Suffrage Organizations: National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage and state-level groups

The National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS) was the most prominent anti-suffrage organization in the United States, founded in 1911 to counter the growing momentum of the women's suffrage movement. With a membership comprising primarily upper-class women, the NAOWS argued that suffrage would disrupt traditional gender roles, overburden women, and undermine the family structure. Their slogan, “Let women be women, and let men be men,” encapsulated their belief in a rigidly defined social order. The organization published *The Woman Patriot*, a weekly newspaper that disseminated anti-suffrage propaganda, and coordinated efforts with state-level groups to lobby against suffrage legislation.

State-level anti-suffrage organizations mirrored the NAOWS’s mission but tailored their strategies to local contexts. For instance, the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women (MAOFESW) emphasized the argument that women’s political involvement would neglect their domestic duties, while the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage focused on the potential for suffrage to corrupt women’s moral influence. These groups often collaborated with political parties, particularly the Democratic Party in the South, which feared that women’s suffrage would empower African American women and challenge white supremacy. State organizations also hosted public debates, circulated petitions, and testified before legislative committees to sway public opinion and policymakers.

Analyzing the tactics of these organizations reveals a deliberate appeal to emotion and tradition rather than logic. Anti-suffrage literature frequently depicted suffragists as unwomanly, radical, or neglectful of their families, leveraging societal anxieties about gender norms. For example, the NAOWS distributed posters showing a suffragist abandoning her crying child to attend a political rally, a stark contrast to the idealized image of the devoted mother. This emotional manipulation was particularly effective among middle- and upper-class women who feared the erosion of their social status if gender roles were redefined.

Despite their efforts, anti-suffrage organizations faced an uphill battle as the suffrage movement gained momentum. By 1917, the NAOWS’s arguments began to lose traction, especially as women’s contributions during World War I challenged notions of their incapacity for public life. The passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 marked the end of their influence, though their legacy persists in debates about gender roles and political participation. Studying these organizations offers insight into the strategies used to resist social change and the enduring power of traditional ideologies in shaping public discourse.

To understand the impact of anti-suffrage organizations today, consider their role in highlighting the complexities of social reform. While their arguments may seem regressive, they underscore the importance of addressing cultural anxieties when advocating for change. Modern movements can learn from this history by framing progressive policies in ways that respect tradition while advancing equality. For instance, emphasizing how gender equality strengthens families—a core concern of anti-suffragists—can bridge divides and build broader support for transformative initiatives.

NPR's Political Stance: Unbiased Reporting or Liberal Slant?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Tactics Used: Propaganda, petitions, and lobbying to block suffrage legislation

The anti-suffrage movement employed a multifaceted strategy to thwart women's voting rights, leveraging propaganda, petitions, and lobbying with surgical precision. Their propaganda machine churned out posters, pamphlets, and newspaper articles that painted suffragists as unwomanly, radical, and a threat to the family structure. One common tactic was to depict suffragists as neglectful mothers, abandoning their children to pursue political power. These materials often used emotional appeals, warning of societal upheaval if women were granted the vote. For instance, a widely circulated poster from the early 20th century showed a suffragist in a suit, briefcase in hand, while a crying child clung to her skirt, with the caption, "Who will care for the children?" Such imagery aimed to evoke fear and guilt, targeting both men and women who valued traditional gender roles.

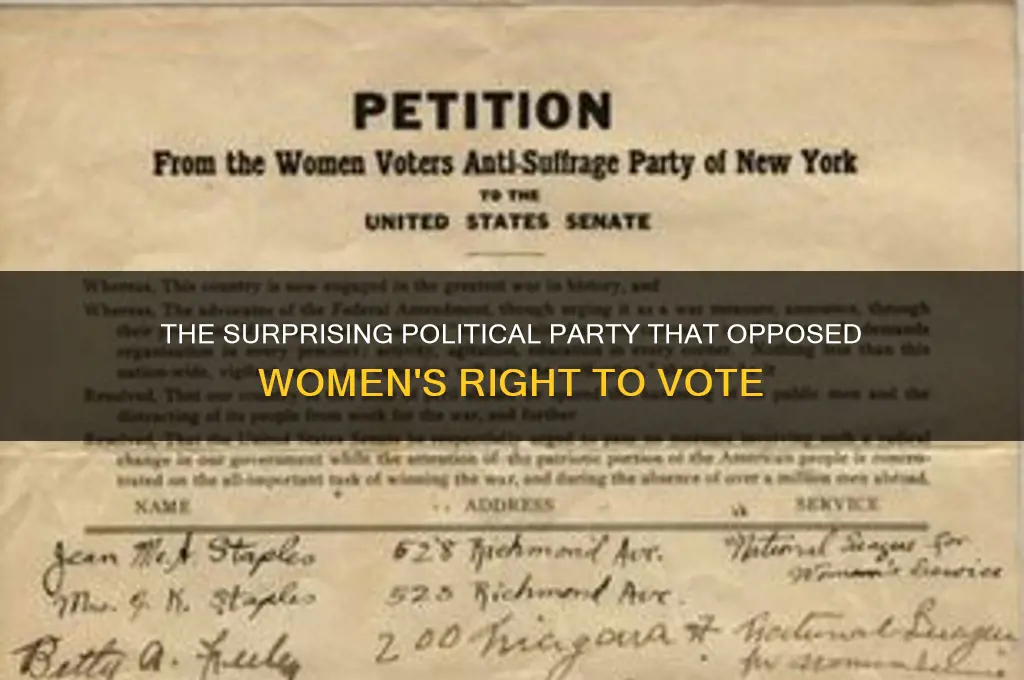

Petitions were another cornerstone of their strategy, providing a veneer of grassroots opposition. Anti-suffrage organizations meticulously gathered signatures from women who claimed to oppose their own enfranchisement. These petitions were then presented to legislators as proof that women themselves did not want the vote. For example, in the United Kingdom, the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League collected over 200,000 signatures in 1910, a number they touted as evidence of widespread female opposition. However, critics pointed out that many signers were coerced or misinformed, and the petitions often included duplicate names. Despite these flaws, the petitions served their purpose, creating the illusion of a divided female population and undermining the suffragists’ claims of universal female support.

Lobbying efforts were perhaps the most effective tactic, as anti-suffrage groups cultivated relationships with politicians to block legislation. These groups, often led by wealthy and influential women, used their social status to gain access to lawmakers. They argued that women’s suffrage would disrupt the natural order, lead to moral decay, and burden women with responsibilities outside the home. In the United States, the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NAOWS) was particularly adept at this, hosting private meetings with senators and representatives to present their case. Their lobbying was so successful that in 1917, they helped defeat a federal suffrage amendment in the Senate by just two votes. This demonstrates how targeted, personal persuasion can sway even high-stakes political decisions.

A comparative analysis reveals that these tactics were not isolated but often worked in tandem. Propaganda created a hostile public opinion, petitions provided a facade of legitimacy, and lobbying translated this opposition into political action. For instance, after a propaganda campaign linked suffrage to socialism, petitions surged in conservative districts, and legislators became more resistant to reform. This synergy highlights the sophistication of the anti-suffrage movement, which understood the importance of aligning public sentiment with political pressure.

In conclusion, the anti-suffrage movement’s use of propaganda, petitions, and lobbying was a calculated and effective strategy to delay women’s voting rights. While their efforts ultimately failed, they provide a cautionary tale about the power of misinformation and organized opposition. Modern activists can learn from this history by recognizing how these tactics are still used today to resist social change. Understanding these methods not only sheds light on the past but also equips us to counter similar strategies in ongoing struggles for equality.

Understanding Political Law: Shaping Societies, Policies, and Governance

You may want to see also

Political Parties: Conservative factions within Republican and Democratic parties resisted women's voting rights

The fight for women's suffrage in the United States was not merely a battle against a single political party but a complex struggle within both major parties. Conservative factions within the Republican and Democratic parties played significant roles in resisting the expansion of voting rights to women, often for reasons tied to regional, cultural, and economic interests. Understanding this internal resistance sheds light on the nuanced political landscape of the early 20th century.

Consider the Republican Party, often associated with progressive reforms during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. While many Republicans supported women's suffrage, particularly in the North, conservative factions in the party, especially in the West and Midwest, were wary of the movement. These factions feared that granting women the vote would disrupt traditional social structures and potentially empower immigrant or minority communities, whose votes they deemed unpredictable. For instance, in states like California, conservative Republicans opposed suffrage initiatives, arguing that women’s involvement in politics would undermine family values and economic stability. This resistance highlights how regional conservatism within the party slowed progress, even as national leadership occasionally voiced support.

Similarly, the Democratic Party, dominated by Southern conservatives, was a stronghold of opposition to women's suffrage. Southern Democrats feared that extending the vote to women, particularly white women, could indirectly empower African Americans by setting a precedent for broader voting rights. This concern was deeply rooted in the Jim Crow era’s racial hierarchy. For example, during the 1910s, Southern Democratic leaders in Congress consistently blocked federal suffrage amendments, arguing that states’ rights should prevail over federal intervention. Even outside the South, conservative Democrats in urban areas resisted suffrage, viewing it as a threat to their political control. This internal party resistance demonstrates how regional and racial anxieties shaped opposition to women’s voting rights.

A comparative analysis reveals that while the reasons for resistance differed between conservative factions in the two parties, the underlying theme was a shared fear of change. Republicans in the West and Midwest worried about social and economic upheaval, while Southern Democrats were preoccupied with maintaining racial control. Both factions leveraged their influence within their respective parties to delay suffrage, often by framing it as a states’ rights issue or a threat to traditional values. This strategic obstruction underscores the importance of understanding intra-party dynamics in historical movements.

Practical takeaways from this history are clear: political progress often requires navigating resistance not just from external opponents but from within one’s own party. Advocates for reform must address the specific fears and interests of conservative factions, whether through education, coalition-building, or strategic compromises. For instance, suffragists eventually succeeded by framing women’s voting rights as a moral and patriotic duty, appealing to conservative values while pushing for change. This approach offers a blueprint for modern activists facing similar intra-party challenges.

In conclusion, the resistance to women’s suffrage within conservative factions of both the Republican and Democratic parties was a critical yet often overlooked aspect of the movement. By examining these internal dynamics, we gain a deeper understanding of the complexities of political change and the strategies needed to overcome entrenched opposition. This history serves as a reminder that progress is rarely linear and often requires addressing the fears and interests of those most resistant to change.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s Political Party Affiliation Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Democratic Party was the primary political party opposed to women's suffrage, particularly in the South, due to concerns about the political power of African American women and the potential shift in voting demographics.

While some individual Republicans opposed women's suffrage, the Republican Party as a whole was generally supportive of the movement, with the 19th Amendment being championed by Republican leaders in Congress.

Yes, conservative factions within both the Democratic and Republican parties opposed women's suffrage, often arguing that it would disrupt traditional gender roles and family structures.

No, the Progressive Party, led by figures like Theodore Roosevelt, generally supported women's suffrage as part of its broader reform agenda to expand democracy and civic participation.

The Conservative Party in the UK was initially more resistant to women's suffrage compared to the Liberal Party, though opinions varied within the party, and some Conservatives eventually supported suffrage reforms.