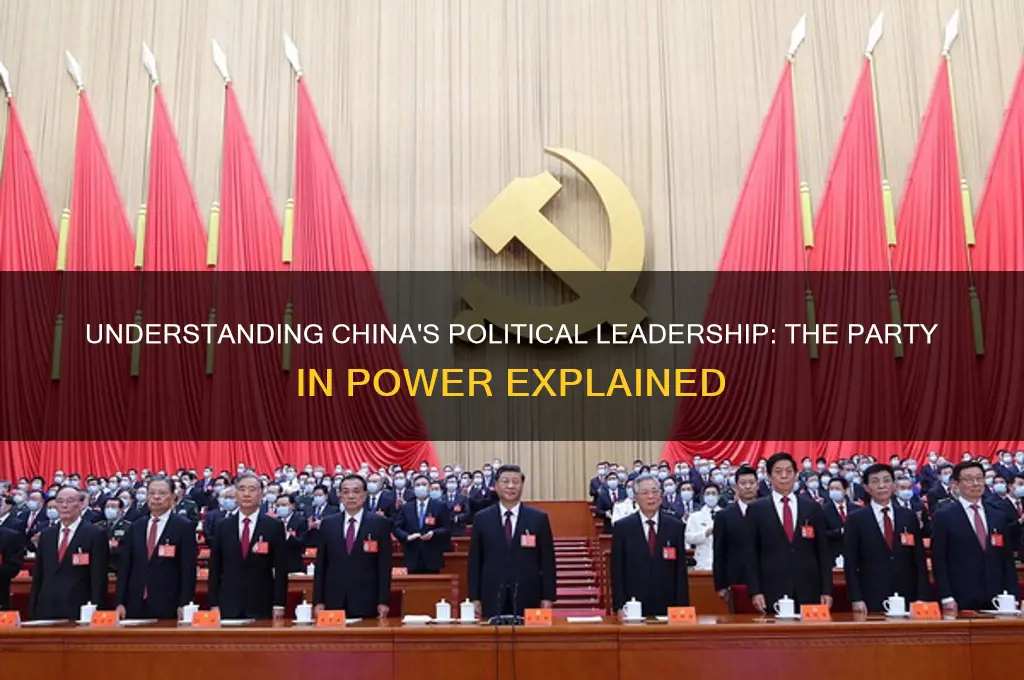

China is governed by the Communist Party of China (CPC), which has held sole political power since the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949. As the country's ruling party, the CPC operates under a one-party system, with its General Secretary, currently Xi Jinping, serving as the paramount leader. The CPC's dominance is enshrined in the Chinese Constitution, and it controls all levels of government, the military, and key institutions, making it the central authority in shaping China's domestic and foreign policies.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Communist Party of China (CPC): Dominant ruling party since 1949, adhering to socialism with Chinese characteristics

- One-Party System: CPC maintains sole political power, with no legal opposition parties allowed

- General Secretary: Xi Jinping, top leader, holds paramount authority over party and state

- National Congress: Highest CPC organ, meets every five years to set policies and elect leaders

- United Front Strategy: CPC works with minor parties under its leadership to maintain unity

Communist Party of China (CPC): Dominant ruling party since 1949, adhering to socialism with Chinese characteristics

The Communist Party of China (CPC) has been the sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China since its founding in 1949, marking over seven decades of uninterrupted governance. This longevity is unparalleled among major global powers and underscores the CPC's unique ability to adapt and maintain control in a rapidly changing world. The party's dominance is enshrined in China's constitution, which explicitly states that the CPC leads the Chinese government and society, a principle known as the "leadership of the Party."

To understand the CPC's enduring rule, one must examine its ideological framework: socialism with Chinese characteristics. This concept, introduced by Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s, represents a pragmatic blend of Marxist principles and market economics. Unlike traditional socialist models, the CPC has embraced economic liberalization while retaining tight political control. This hybrid system has allowed China to achieve unprecedented economic growth, lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty and transforming the nation into a global economic powerhouse. For instance, since the reforms began in 1978, China's GDP has grown at an average annual rate of over 9%, a feat unmatched by any other major economy.

However, the CPC's adherence to socialism with Chinese characteristics is not without controversy. Critics argue that the party's prioritization of stability and control has led to restrictions on political freedoms and human rights. The CPC justifies these measures as necessary to maintain social order and prevent the chaos it associates with Western-style democracy. This approach is exemplified by the party's handling of dissent, such as the crackdown on the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 and its policies in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. These actions highlight the CPC's commitment to its own definition of socialism, which emphasizes collective welfare over individual liberties.

A comparative analysis reveals the CPC's distinctiveness among ruling parties worldwide. Unlike democratic parties that face regular electoral challenges, the CPC operates within a one-party system, eliminating political competition. This structure allows for long-term planning and policy implementation, as seen in initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative and the Made in China 2025 plan. However, it also raises questions about accountability and representation. The CPC addresses these concerns through mechanisms like the National People's Congress and local governance structures, which provide channels for citizen input, albeit within the party's framework.

For those seeking to engage with or understand China, recognizing the CPC's central role is essential. The party's policies shape every aspect of Chinese society, from economic development to cultural expression. Practical tips for navigating this landscape include studying the CPC's official documents, such as the party constitution and General Secretary Xi Jinping's speeches, to grasp its priorities and direction. Additionally, understanding the party's organizational structure, including its hierarchy and key decision-making bodies like the Politburo, can provide insights into how policies are formulated and implemented. By focusing on these specifics, one can better comprehend the CPC's dominance and its impact on China's trajectory.

Exploring Georgia's Political Landscape: Parties Represented in the State

You may want to see also

One-Party System: CPC maintains sole political power, with no legal opposition parties allowed

China operates under a one-party system, with the Communist Party of China (CPC) holding absolute political power. This structure is enshrined in the country’s constitution, which explicitly states that the CPC leads all aspects of Chinese society. Unlike democratic systems where multiple parties compete for power, China’s political landscape is designed to ensure the CPC’s dominance, with no legal avenue for opposition parties to form or challenge its authority. This system is not merely a theoretical construct but a practical framework that shapes governance, policy-making, and public life.

The CPC’s monopoly on power is maintained through a combination of institutional control and ideological reinforcement. All government positions, from local to national levels, are held by CPC members or those aligned with its agenda. The party’s influence extends into key sectors such as education, media, and the military, ensuring that its narrative remains unchallenged. For instance, textbooks in Chinese schools emphasize the CPC’s role in national development, while state-controlled media outlets amplify its achievements and suppress dissenting voices. This comprehensive control minimizes the possibility of alternative political movements gaining traction.

Critics argue that the one-party system stifles political diversity and limits accountability. Without opposition parties, there is no formal mechanism for challenging the CPC’s policies or decisions. However, proponents counter that this system fosters stability and enables long-term planning, free from the short-termism often associated with electoral cycles in multiparty democracies. For example, China’s rapid economic growth and infrastructure development over the past decades are frequently cited as evidence of the system’s effectiveness. Yet, this comes at the cost of individual political freedoms and the absence of competitive elections at the national level.

Understanding the CPC’s role requires recognizing its dual function as both a political party and a governing institution. It operates through a hierarchical structure, with the Politburo Standing Committee at its apex, making it both the decision-maker and the enforcer of policies. This dual role eliminates the checks and balances typical in multiparty systems, concentrating power in the hands of a select few. While this allows for swift decision-making, it also raises concerns about transparency and the potential for abuse of power.

For those studying or engaging with China’s political system, it’s essential to grasp the CPC’s centrality. Practical tips include focusing on the party’s five-year plans, which outline its policy priorities, and analyzing its internal leadership dynamics, as shifts within the CPC often signal broader changes in governance. Additionally, understanding the role of mass organizations like the Communist Youth League and trade unions, which operate under the CPC’s guidance, provides insight into how the party maintains its influence across society. This knowledge is crucial for navigating China’s political landscape, whether for academic research, business, or diplomacy.

Exploring the Existence of Nazi-Aligned Political Parties in America

You may want to see also

General Secretary: Xi Jinping, top leader, holds paramount authority over party and state

Xi Jinping's role as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) places him at the apex of China's political hierarchy, wielding authority that surpasses even his titular role as President. This concentration of power is unique among modern nation-states, blending traditional Leninist party structures with a personalized leadership model. Since assuming the General Secretary position in 2012, Xi has systematically consolidated control over key levers of state and party apparatus, eliminating term limits in 2018 and embedding his ideological doctrine, "Xi Jinping Thought," into the CCP constitution.

Understanding Xi's authority requires dissecting the CCP's organizational framework. As General Secretary, he chairs the Politburo Standing Committee, the highest decision-making body, and directly oversees the Central Military Commission, ensuring command over the People's Liberation Army. This dual control over party and military is a cornerstone of his power, historically a prerequisite for unchallenged leadership in China. Xi's influence extends further through his loyalists strategically placed in provincial party committees, state-owned enterprises, and propaganda organs, creating a vertically integrated system of governance.

A comparative lens highlights the distinctiveness of Xi's rule. Unlike democratic systems where power is diffused across branches and term limits are normative, Xi's authority is both centralized and potentially indefinite. This model resembles earlier Chinese strongmen like Mao Zedong but operates within a more bureaucratized and technologically enabled state. Xi's anti-corruption campaigns, while popular domestically, have also served as a tool to sideline rivals and reinforce his dominance, illustrating the dual nature of his leadership as both administrative and coercive.

For observers and policymakers, Xi's paramount authority demands a recalibration of engagement strategies. His emphasis on national rejuvenation, encapsulated in the "Chinese Dream," shapes foreign and domestic policies, from Belt and Road initiatives to technological self-sufficiency. However, this concentration of power introduces risks: policy missteps are less likely to be corrected internally, and ideological rigidity may hinder adaptive governance. Engaging with China under Xi requires navigating a system where the General Secretary's priorities are the nation's priorities, leaving little room for dissent or deviation.

Practically, understanding Xi's role is essential for anyone interacting with Chinese institutions, from businesses seeking market entry to diplomats negotiating trade agreements. His speeches and policy directives, often dense with historical references and party jargon, offer critical insights into future trajectories. For instance, his emphasis on "common prosperity" signals a shift toward reducing inequality, impacting industries from tech to real estate. Monitoring the CCP's internal dynamics, particularly the balance of factions within the Politburo, provides additional context for predicting policy shifts under Xi's leadership.

Exploring Robert Redford's Political Party Affiliation and Activism

You may want to see also

Explore related products

National Congress: Highest CPC organ, meets every five years to set policies and elect leaders

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the sole ruling party in China, and its highest organ is the National Congress. This body, a cornerstone of China’s political system, convenes every five years in a highly orchestrated event that shapes the nation’s trajectory. Unlike frequent legislative sessions in many democracies, the quinquennial rhythm of the National Congress underscores its gravity: it is not merely a procedural gathering but a pivotal moment for policy recalibration and leadership transition. During these sessions, approximately 2,300 delegates from across China’s provinces, regions, and sectors assemble in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People to debate, endorse, and amend the party’s constitution, set long-term goals, and elect key leaders. This five-year cycle ensures continuity while allowing for strategic adjustments in response to domestic and global shifts.

Analytically, the National Congress serves as both a symbolic and functional linchpin of the CCP’s authority. Its decisions are binding on all party members and, by extension, the state apparatus, given the CCP’s dominance in China’s governance structure. The Congress’s role in electing the Central Committee—which in turn selects the Politburo and its Standing Committee—highlights its direct influence on the apex of Chinese leadership. For instance, the 20th National Congress in 2022 saw Xi Jinping secure an unprecedented third term as General Secretary, signaling a consolidation of power and a departure from the two-term norm established after Mao Zedong. This example illustrates how the Congress is not just a rubber-stamp body but a platform for significant political shifts, even if outcomes are often pre-negotiated behind closed doors.

Instructively, understanding the National Congress requires recognizing its dual nature: it is both a ceremonial affirmation of party unity and a substantive forum for policy innovation. Delegates are expected to align with the party line, yet they also bring localized concerns to the table, ensuring that central policies are informed by regional realities. For instance, during the 19th National Congress in 2017, discussions on poverty alleviation and environmental protection reflected grassroots priorities, culminating in policies like the "Beautiful China" initiative. Practical engagement with the Congress’s outcomes involves tracking its communiqués and work reports, which outline five-year plans and ideological directives. These documents are not mere rhetoric; they translate into tangible policies affecting everything from economic development to social welfare.

Persuasively, the National Congress exemplifies the CCP’s ability to balance stability and adaptability—a key to its longevity in power. By convening infrequently but decisively, the Congress avoids the paralysis of constant politicking while ensuring that leadership remains responsive to evolving challenges. Critics argue this system lacks transparency and accountability, but proponents highlight its efficiency in executing long-term strategies, such as China’s rise as a global economic powerhouse. The Congress’s role in electing leaders also fosters a degree of internal competition and meritocracy, as candidates must demonstrate competence and loyalty to ascend the party ranks. This blend of tradition and pragmatism positions the National Congress as a unique institution in contemporary governance.

Comparatively, the National Congress contrasts sharply with legislative bodies in liberal democracies. While parliaments in countries like the United States or the United Kingdom meet regularly and often engage in partisan gridlock, the National Congress operates within a one-party framework, prioritizing consensus over conflict. This difference reflects China’s distinct political philosophy, which emphasizes collective leadership and long-term vision over short-term electoral gains. However, like any system, it has limitations: the absence of opposition parties means alternative viewpoints are often marginalized, and the concentration of power in the CCP raises questions about checks and balances. Nonetheless, the National Congress remains a fascinating study in centralized decision-making, offering insights into how China navigates its complex domestic and international landscape.

Eileen C. Moore's Political Affiliation: Unveiling Her Party Loyalty

You may want to see also

United Front Strategy: CPC works with minor parties under its leadership to maintain unity

The Chinese Communist Party (CPC) has maintained its dominance in China's political landscape since 1949, but its approach to governance is not solely reliant on unilateral control. A key mechanism to ensure stability and unity is the United Front Strategy, which involves the CPC collaborating with eight minor political parties under its leadership. This system, often referred to as "multi-party cooperation and political consultation under CPC leadership," is a unique feature of China's political structure. Unlike Western multiparty systems, these minor parties do not compete for power but instead operate as partners, offering consultative roles and representing specific societal groups.

To understand the United Front Strategy, consider its practical implementation. The CPC invites minor parties like the China Democratic League and the Revolutionary Committee of the Chinese Kuomintang to participate in the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), a key advisory body. Here, these parties submit proposals on issues ranging from economic reform to social welfare. While their influence is limited—final decision-making rests with the CPC—their involvement serves to broaden the CPC’s legitimacy and demonstrate inclusivity. For instance, during the drafting of the 14th Five-Year Plan, minor parties contributed over 5,000 suggestions, many of which were incorporated into the final document. This process not only maintains unity but also creates an illusion of diversity within a one-party state.

A critical analysis reveals the United Front Strategy’s dual purpose: to co-opt potential opposition and to manage societal interests. Minor parties are carefully vetted and must align with the CPC’s principles, ensuring they pose no threat to its authority. Simultaneously, these parties act as conduits for specific constituencies, such as intellectuals, entrepreneurs, or religious groups. By allowing them a platform, the CPC reduces the risk of dissent while projecting an image of unified governance. However, this system is not without risks. Over-reliance on minor parties could dilute the CPC’s direct control, while tokenistic inclusion may undermine their credibility among the public.

For those studying or engaging with China’s political system, understanding the United Front Strategy offers practical insights. First, recognize that minor parties are not independent actors but extensions of the CPC’s governance framework. Second, when analyzing policy decisions, consider the role of these parties in shaping discourse, even if their impact is marginal. Finally, appreciate the strategy’s adaptability: it has allowed the CPC to navigate decades of economic and social transformation while maintaining political stability. This model, though unique, provides a case study in how authoritarian regimes can manage diversity without relinquishing control.

In conclusion, the United Front Strategy is a sophisticated tool for the CPC to consolidate power while maintaining the appearance of unity and inclusivity. By working with minor parties under its leadership, the CPC ensures that diverse voices are heard—on its terms. This approach not only strengthens its legitimacy but also serves as a buffer against potential fragmentation. For observers and participants alike, understanding this mechanism is essential to grasping the intricacies of China’s political system.

Understanding WAPO: Its Role and Influence in Political Journalism

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Communist Party of China (CPC) is the ruling political party in China.

The CPC has been in power since 1949, following the establishment of the People's Republic of China.

Yes, there are eight other legally recognized political parties in China, but they operate under the leadership of the CPC in a system known as the "United Front."

The CPC does not face formal opposition in the Western democratic sense, as China is a one-party state with the CPC holding ultimate political authority.

As of the latest information, Xi Jinping is the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China and the country's paramount leader.