The question of whether there is an American political party explicitly aligned with Nazi ideology is a sensitive and contentious issue. While the United States has a diverse political landscape, no major or officially recognized political party openly advocates for Nazi principles, such as white supremacy, antisemitism, or authoritarianism. However, there are fringe groups and extremist organizations within the country that espouse ideologies similar to Nazism, often operating outside the mainstream political system. These groups, though not formally structured as political parties, occasionally attempt to influence public discourse or infiltrate local politics. The broader concern lies in the rise of far-right movements and the normalization of extremist rhetoric, which has prompted ongoing debates about the boundaries of free speech and the need to combat hate groups in American society.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Context: American Nazi Party's existence and dissolution in the 20th century

- Modern Extremist Groups: White supremacist organizations with Nazi ideologies operating in the U.S

- Political Fringe Parties: Minor parties with far-right, nationalist, or authoritarian platforms

- Legal Boundaries: First Amendment protections versus hate speech and incitement laws

- Mainstream Politics: Influence of Nazi-adjacent ideas in contemporary American political discourse

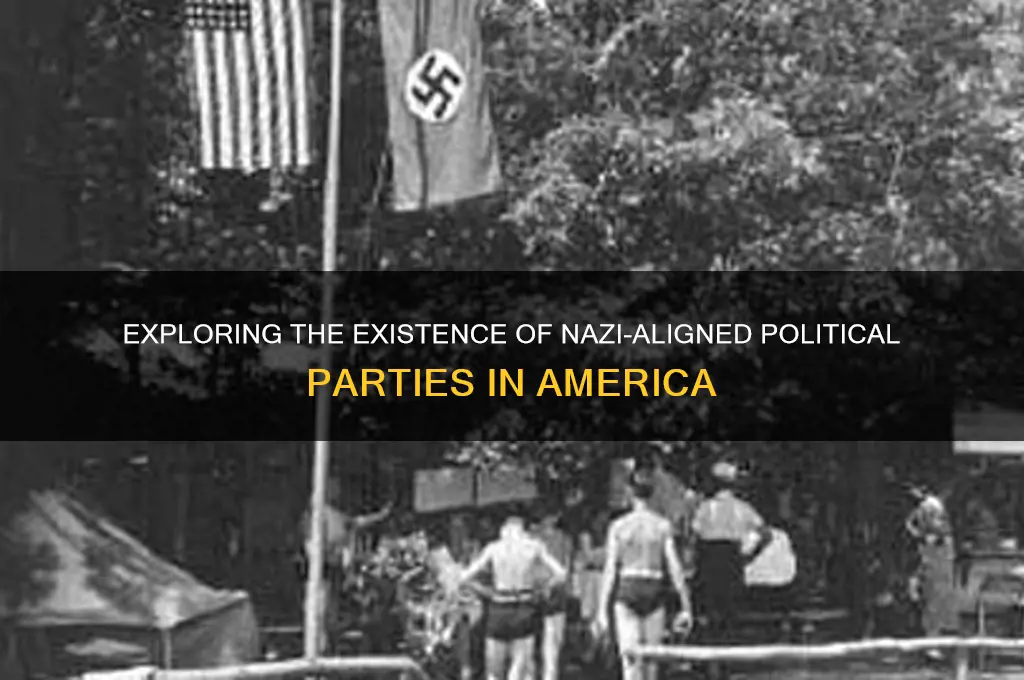

Historical Context: American Nazi Party's existence and dissolution in the 20th century

The American Nazi Party, founded in 1959 by George Lincoln Rockwell, emerged as a stark manifestation of extremist ideology in the United States during the Cold War era. Rockwell, a former Navy commander, modeled the party after the German Nazi Party, adopting its symbols, rhetoric, and goals. The group’s formation coincided with the civil rights movement, which it vehemently opposed, advocating instead for racial segregation and white supremacy. Despite its provocative tactics, such as uniformed marches and public demonstrations, the party never gained significant political traction, remaining a fringe movement with an estimated membership of only a few hundred at its peak.

Analyzing the party’s dissolution in the 1960s reveals a combination of internal strife and external pressures. Rockwell’s assassination in 1967 by a disgruntled party member marked the beginning of the end. His successor, Matthias Koehl, failed to maintain cohesion, and the organization splintered into smaller, even more radical factions. Externally, the party faced relentless opposition from civil rights activists, government surveillance under the FBI’s COINTELPRO program, and widespread public condemnation. By the 1970s, the American Nazi Party had effectively ceased to exist as a unified entity, though its legacy persisted in the form of scattered neo-Nazi groups.

A comparative examination of the American Nazi Party’s trajectory highlights its stark contrast with European fascist movements. Unlike its European counterparts, which often gained state power through political manipulation or force, the American Nazi Party was marginalized from its inception. The United States’ strong democratic institutions, legal protections against hate speech, and a largely intolerant public stance toward Nazi ideology acted as barriers to its growth. This distinction underscores the importance of societal and institutional resilience in preventing extremist ideologies from taking root.

From a practical standpoint, the history of the American Nazi Party serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked extremism. While the party’s dissolution was a victory for democracy, its remnants continue to influence contemporary white supremacist movements. To combat such ideologies, proactive measures are essential: education about historical fascism, robust legal frameworks against hate groups, and community-based initiatives to address the root causes of radicalization. Understanding this history equips society to recognize and counter similar threats before they escalate.

Finally, the instructive takeaway from the American Nazi Party’s existence lies in its demonstration of how extremist movements can be neutralized. The combination of internal disorganization, external opposition, and a hostile public environment proved fatal to the party’s ambitions. This historical case study emphasizes the need for vigilance, unity, and decisive action in confronting hate groups. By learning from the past, society can better safeguard democratic values and prevent the resurgence of such dangerous ideologies.

Understanding FDR's Political Party: A Comprehensive Historical Analysis

You may want to see also

Modern Extremist Groups: White supremacist organizations with Nazi ideologies operating in the U.S

While there is no officially recognized American political party explicitly advocating Nazi ideologies, the United States is not immune to the presence of extremist groups that espouse white supremacist and neo-Nazi beliefs. These organizations, often operating in the shadows, pose a significant threat to social cohesion and public safety. Understanding their structure, tactics, and motivations is crucial for countering their influence.

One prominent example is the Atomwaffen Division (AWD), a neo-Nazi terrorist network known for its extreme violence and recruitment of young, disaffected individuals. AWD members have been linked to multiple murders and acts of domestic terrorism. Their strategy involves exploiting online platforms to spread propaganda, recruit members, and incite violence. Unlike traditional political parties, AWD operates as a decentralized cell structure, making it harder for law enforcement to dismantle. This group exemplifies how extremist ideologies can manifest in the absence of formal political representation, relying instead on underground networks and digital mobilization.

Another notable organization is the National Socialist Movement (NSM), which openly identifies with Nazi symbolism and ideology. NSM has attempted to gain visibility through public rallies, such as the 2017 "Unite the Right" rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, which turned deadly. While NSM has sought to present itself as a legitimate political movement, its efforts have been largely marginalized due to widespread public condemnation and legal challenges. Despite this, the group continues to attract adherents through its emphasis on racial purity and anti-Semitic conspiracy theories, highlighting the enduring appeal of Nazi-inspired ideologies in certain fringe communities.

The rise of these groups underscores the importance of proactive measures to counter extremism. Educational initiatives that promote critical thinking and cultural literacy can help inoculate individuals against extremist narratives. Community-based interventions, such as mentorship programs for at-risk youth, can address the root causes of radicalization, such as alienation and lack of opportunity. Additionally, policy reforms that strengthen hate crime legislation and enhance law enforcement capabilities are essential for disrupting extremist activities.

In conclusion, while there is no formal Nazi political party in the U.S., the presence of white supremacist organizations with Nazi ideologies remains a pressing concern. By understanding their tactics and addressing the underlying factors that fuel their growth, society can work toward mitigating the threat they pose. Vigilance, education, and collective action are key to safeguarding democratic values and ensuring a safer, more inclusive future.

Can Political Parties Establish Their Own Military Forces?

You may want to see also

Political Fringe Parties: Minor parties with far-right, nationalist, or authoritarian platforms

In the United States, political fringe parties with far-right, nationalist, or authoritarian platforms have existed on the margins of the political spectrum, often operating under the radar of mainstream discourse. These groups, while numerically insignificant, pose a unique challenge to democratic norms due to their extremist ideologies. One notable example is the National Socialist Movement (NSM), which openly identifies with Nazi symbolism and rhetoric. Though not a formal political party, the NSM has attempted to influence local elections and public opinion through rallies and propaganda. Their existence raises questions about the boundaries of free speech and the resilience of democratic institutions in the face of such extremism.

Analyzing the structure of these fringe parties reveals a common pattern: they often lack the organizational capacity to compete in national elections but focus on grassroots mobilization and online recruitment. Platforms like Gab and Telegram have become breeding grounds for their ideologies, allowing them to bypass mainstream media censorship. For instance, the American Identity Movement (formerly Identity Evropa) uses sophisticated branding and targeted messaging to appeal to younger demographics, framing their white nationalist agenda as a cultural preservation movement. This strategic use of technology and aesthetics underscores the adaptability of these groups, making them harder to counter through traditional political means.

From a comparative perspective, American fringe parties differ from their European counterparts in their level of institutionalization. In countries like Germany, where historical memory of Nazism is deeply ingrained, parties like the AfD (Alternative for Germany) operate within the political system but face stringent legal restrictions on extremist activities. In contrast, the U.S. lacks a comprehensive legal framework to curb such groups, relying instead on societal rejection and counter-protests. This difference highlights the importance of cultural and historical context in shaping the trajectory of far-right movements.

To address the challenge posed by these fringe parties, a multi-pronged approach is necessary. First, educational initiatives must focus on media literacy and critical thinking to inoculate the public against extremist narratives. Second, social media platforms need to enforce stricter policies against hate speech, though this must be balanced with concerns about censorship. Finally, policymakers should consider legislative measures to prevent these groups from exploiting loopholes in campaign finance and assembly laws. While these steps may not eliminate fringe parties entirely, they can mitigate their ability to disrupt democratic processes and normalize extremist ideologies.

In conclusion, while there is no formal "Nazi party" in the U.S., fringe groups espousing far-right, nationalist, or authoritarian platforms continue to operate in the shadows of American politics. Their persistence serves as a reminder of the ongoing struggle to uphold democratic values in an era of polarization and technological change. By understanding their strategies and addressing their root causes, society can better safeguard itself against the corrosive effects of extremism.

Are Political Party Names Capitalized? A Grammar Guide for Politics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$23.35 $29.99

$9.99 $17.05

Legal Boundaries: First Amendment protections versus hate speech and incitement laws

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees freedom of speech, a cornerstone of American democracy. However, this protection is not absolute, particularly when speech crosses into the realm of hate speech or incitement to violence. The question of whether there is an American political party for Nazis—or any group advocating extremist ideologies—raises critical issues about where legal boundaries are drawn between protected speech and unlawful conduct.

Analytically, the Supreme Court has historically upheld broad protections for speech, even when it is offensive or hateful. In *Brandenburg v. Ohio* (1969), the Court established the "imminent lawless action" test, which holds that speech is only unprotected if it is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to do so. This means that merely expressing racist, antisemitic, or Nazi ideologies—as abhorrent as they may be—is generally protected under the First Amendment. However, organizing or advocating for violence based on these ideologies crosses the line into illegal territory. For instance, a political party openly calling for the overthrow of the government or the harm of specific groups could face legal consequences, even if it cloaks its message in political rhetoric.

Instructively, individuals and groups must navigate these legal boundaries with caution. While forming a political party is a protected activity, the methods and messages employed can quickly become unlawful. For example, using public platforms to threaten violence, organize hate crimes, or promote discrimination based on race, religion, or ethnicity can lead to criminal charges. Practical tips include ensuring that all political activities remain nonviolent, avoid direct calls for harm, and focus on lawful advocacy. Organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) often provide guidance on how to exercise free speech rights while staying within legal limits, though they have also defended hate groups in court to uphold the principle of free speech.

Persuasively, the tension between free speech and hate speech laws reflects deeper societal values. While the U.S. prioritizes individual expression, other countries, such as Germany, have stricter laws prohibiting Nazi symbolism and Holocaust denial. Critics argue that allowing hate speech normalizes extremism, while proponents contend that censorship undermines democratic principles. This debate highlights the challenge of balancing protection from harm with protection of speech. For those considering involvement in controversial political movements, understanding these legal nuances is essential to avoid unintended legal consequences.

Comparatively, the absence of a formal Nazi political party in the U.S. does not mean such ideologies do not exist. Extremist groups often operate under different names or as loosely organized networks, leveraging social media and encrypted platforms to spread their message. Unlike in countries with explicit bans on hate groups, U.S. law focuses on the actions rather than the beliefs of these organizations. This approach allows authorities to target illegal behavior while respecting constitutional rights. For example, the Proud Boys and other far-right groups have faced legal scrutiny not for their beliefs but for their involvement in violence, such as the January 6, 2021, Capitol riot.

In conclusion, the legal boundaries between First Amendment protections and hate speech or incitement laws are complex but crucial. While the U.S. allows for the expression of even the most repugnant ideologies, it draws a firm line at speech that incites imminent violence or lawlessness. Navigating these boundaries requires a clear understanding of legal precedents, careful messaging, and a commitment to nonviolent advocacy. As society grapples with the rise of extremist movements, this framework remains a vital tool for upholding both freedom and safety.

Can Politics Evolve? Exploring Hope for a Better Political Future

You may want to see also

Mainstream Politics: Influence of Nazi-adjacent ideas in contemporary American political discourse

While there is no officially recognized Nazi political party in the United States, the specter of Nazi-adjacent ideas haunts contemporary American political discourse. These ideas, often cloaked in euphemisms and dog whistles, seep into mainstream conversations, normalizing xenophobia, authoritarianism, and racial hierarchy.

A prime example is the rise of "America First" rhetoric, a phrase with historical ties to isolationist movements sympathetic to Nazi Germany. Today, it's wielded to justify anti-immigrant policies, protectionist trade measures, and a general distrust of international cooperation. This echoes the Nazi regime's emphasis on national purity and self-sufficiency, albeit in a more subtle and palatable form.

The targeting of marginalized groups, a hallmark of Nazi ideology, also finds disturbing parallels. The demonization of immigrants, particularly those from Latin America and the Middle East, mirrors the dehumanization of Jews and other "undesirable" groups under Nazi rule. Rhetoric about "replacing" native-born Americans with foreigners echoes the Nazi myth of the "stab in the back," blaming societal ills on internal enemies. This language, often amplified by social media and fringe media outlets, creates a climate of fear and suspicion, paving the way for discriminatory policies and violence.

The erosion of democratic norms and the glorification of strongman leadership further reflect the influence of Nazi-adjacent ideas. Attacks on the free press, the judiciary, and electoral processes, coupled with admiration for authoritarian figures, echo the Nazi regime's dismantling of democratic institutions. This trend, often disguised as "draining the swamp" or "taking back control," undermines the very foundations of American democracy, replacing it with a vision of hierarchical order and unquestioning obedience.

Recognizing these parallels is crucial for combating the insidious creep of Nazi-adjacent ideas into mainstream politics. It requires vigilance, critical thinking, and a commitment to democratic values. We must challenge xenophobic rhetoric, expose historical parallels, and amplify the voices of those targeted by hate speech. Only by confronting these dangers head-on can we ensure that the horrors of the past remain firmly in the past.

Washington's Stance on Political Parties: A Historical Perspective

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, there is no officially recognized American political party that identifies as a Nazi party. Nazi ideology is widely condemned in the United States, and such a party would not be legally or socially accepted.

Yes, there are extremist groups in the U.S. that promote white supremacist, neo-Nazi, or fascist ideologies, but they operate outside the mainstream political system and are not recognized as legitimate political parties.

While the First Amendment protects freedom of speech, the U.S. legal system does not allow political parties or organizations that advocate violence, genocide, or the overthrow of the government, which are core tenets of Nazi ideology.

No, mainstream American political parties, such as the Democratic and Republican parties, do not support or endorse Nazi ideology. Such views are universally rejected in mainstream U.S. politics.