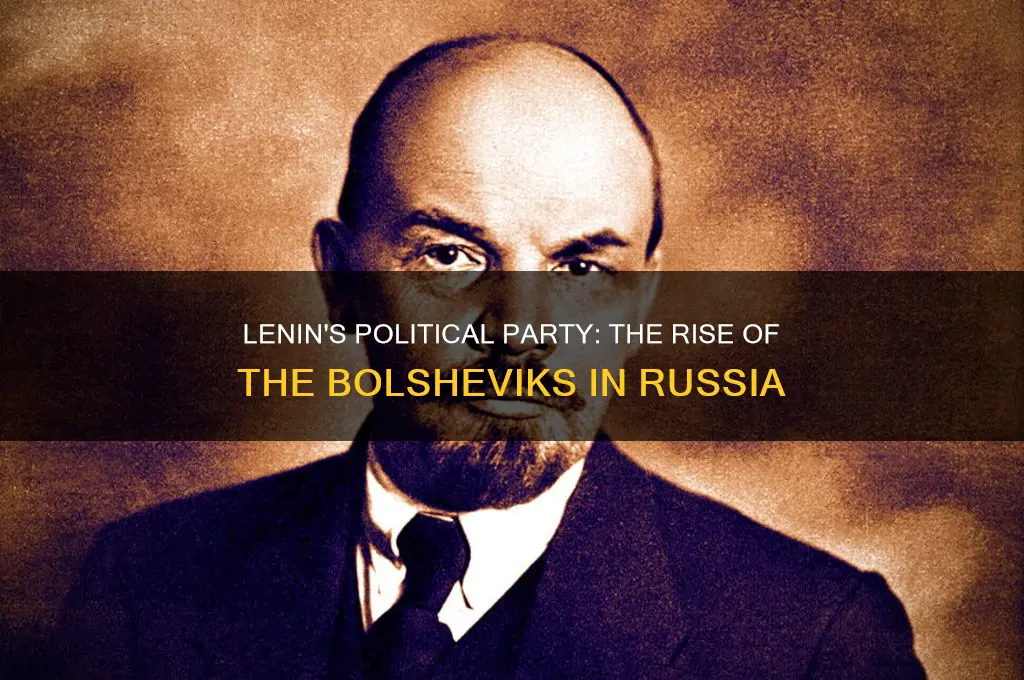

Vladimir Lenin, a pivotal figure in the Russian Revolution and the founding leader of the Soviet Union, was a member of the Bolshevik Party, a faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). The Bolsheviks, whose name derives from the Russian word for majority, emerged as a radical Marxist group advocating for a proletarian revolution and the establishment of a socialist state. Under Lenin's leadership, the Bolsheviks seized power during the October Revolution of 1917, overthrowing the Provisional Government and paving the way for the creation of the world's first socialist state. The Bolshevik Party later renamed itself the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks), which became the dominant political force in the Soviet Union until its dissolution in 1991. Lenin's ideological and organizational contributions were central to the party's success and its enduring impact on global politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), later the Bolshevik Party |

| Ideology | Marxism, Leninism, Communism |

| Founder | Vladimir Lenin |

| Founded | 1898 (RSDLP), 1912 (Bolshevik faction) |

| Dissolved | 1918 (RSDLP), 1952 (Bolshevik Party renamed to Communist Party of the Soviet Union) |

| Headquarters | Saint Petersburg, later Moscow |

| Newspaper | Iskra (The Spark), Pravda (Truth) |

| Key Figures | Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Joseph Stalin, Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev |

| Political Position | Far-left |

| Main Goal | Overthrow of the Tsarist regime, establishment of a socialist state, and ultimately a communist society |

| Tactics | Revolutionary violence, vanguard party, dictatorship of the proletariat |

| Major Achievements | October Revolution (1917), establishment of the Soviet Union (1922) |

| Legacy | Foundation of the Soviet Union, global influence on communist movements, controversial legacy due to authoritarianism and human rights abuses |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Bolshevik Party Founding: Lenin co-founded the Bolshevik Party, a faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

- Ideological Basis: Bolsheviks advocated Marxism, focusing on proletarian revolution and dictatorship of the proletariat

- Revolution Role: Bolsheviks led the October Revolution, overthrowing the Provisional Government under Lenin's leadership

- Party Renaming: In 1918, Bolsheviks renamed themselves the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

- Lenin's Leadership: Lenin served as the party's leader until his death in 1924, shaping its policies

Bolshevik Party Founding: Lenin co-founded the Bolshevik Party, a faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

Vladimir Lenin’s role in co-founding the Bolshevik Party was a pivotal moment in the history of Russian and global politics. Emerging as a faction within the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) in 1903, the Bolsheviks were defined by their commitment to a centralized, disciplined vanguard party capable of leading a proletarian revolution. Lenin’s *What Is to Be Done?* (1902) laid the ideological groundwork, arguing that the working class could not achieve revolutionary consciousness spontaneously but required guidance from a professional revolutionary cadre. This vision sharply contrasted with the Mensheviks, who favored a broader, more decentralized approach. The split at the RSDLP’s Second Congress was not merely organizational but reflected deeper disagreements about the nature of revolution and the role of the party in achieving it.

To understand the Bolsheviks’ founding, consider their strategic focus on urban industrial workers as the primary agents of change. Lenin believed that Russia’s unique conditions—a semi-feudal society with a growing industrial proletariat—required a party that could bridge the gap between Marxist theory and revolutionary practice. Unlike the Mensheviks, who aligned with the liberal bourgeoisie, the Bolsheviks aimed to overthrow the tsarist regime and establish a dictatorship of the proletariat. This required a tightly organized party with a clear hierarchy, where decisions were made swiftly and executed decisively. Practical steps included establishing underground cells, publishing revolutionary literature, and mobilizing workers through strikes and protests, all under the banner of *Iskra*, the party’s newspaper.

A comparative analysis highlights the Bolsheviks’ distinctiveness. While other socialist movements in Europe emphasized gradual reform or parliamentary tactics, Lenin’s party prioritized immediate, radical change. For instance, the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) focused on electoral gains and trade union cooperation, whereas the Bolsheviks saw these as secondary to direct revolutionary action. This difference was not just theoretical but had practical implications: the Bolsheviks’ willingness to use insurrectionary tactics, as seen in the 1917 October Revolution, set them apart from their European counterparts. Their success in seizing power demonstrated the effectiveness of Lenin’s model, though it also raised questions about the long-term sustainability of such a centralized system.

Persuasively, the Bolshevik Party’s founding was a masterclass in ideological clarity and organizational discipline. Lenin’s ability to unite disparate revolutionary elements under a single banner was unparalleled. However, this strength also became a weakness, as the party’s rigid structure left little room for internal dissent or adaptation. For modern political movements, the takeaway is clear: while a focused, disciplined approach can achieve revolutionary goals, it risks alienating broader support and stifling innovation. Balancing unity with flexibility remains a challenge for any organization seeking transformative change. The Bolsheviks’ legacy serves as both a blueprint and a cautionary tale for those navigating the complexities of political mobilization.

The Birth of Federal Income Tax: Which Party and When?

You may want to see also

Ideological Basis: Bolsheviks advocated Marxism, focusing on proletarian revolution and dictatorship of the proletariat

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were staunch advocates of Marxism, a revolutionary ideology that sought to dismantle capitalist structures and establish a society governed by the working class. At the core of their belief system was the concept of the proletarian revolution, a violent uprising of the working class against the bourgeoisie. This revolution was not merely a political act but a necessary step to overthrow the exploitative capitalist system and redistribute wealth and power to those who created it—the proletariat. Lenin’s interpretation of Marxism emphasized the urgency of this revolution, particularly in the context of Russia’s semi-feudal economy, where industrialization had created a sizable but oppressed working class.

Following the revolution, the Bolsheviks envisioned the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat, a transitional phase where the working class would hold political power to suppress the bourgeoisie and reorganize society. This dictatorship was not about individual rule but collective governance by the proletariat, guided by the principles of Marxism. Lenin argued that this phase was essential to dismantle capitalist remnants, eliminate class distinctions, and pave the way for a classless, stateless communist society. Unlike liberal democracies, which the Bolsheviks viewed as tools of bourgeois oppression, this dictatorship was to be a mechanism for liberation, ensuring the proletariat’s dominance until the conditions for communism were met.

To achieve these goals, the Bolsheviks employed a highly disciplined and centralized party structure, known as democratic centralism. This system ensured unity of action and ideological coherence, critical for mobilizing the masses and executing revolutionary objectives. Lenin’s *What Is to Be Done?* (1902) outlined this strategy, emphasizing the role of a vanguard party composed of professional revolutionaries to lead the proletariat. This approach distinguished the Bolsheviks from other socialist groups, who often favored gradual reform or decentralized movements, and underscored their commitment to a swift, decisive revolution.

A comparative analysis reveals the Bolsheviks’ unique adaptation of Marxism. While Marx had theorized about the proletarian revolution and dictatorship of the proletariat in advanced capitalist societies, Lenin applied these concepts to Russia, a country with a predominantly agrarian economy. This required significant ideological flexibility, such as the alliance with the peasantry (as seen in the Decree on Land) to broaden the revolutionary base. Lenin’s *April Theses* (1917) further exemplified this adaptation, calling for an immediate transition to socialism in Russia, bypassing the capitalist stage Marx had deemed necessary.

In practice, the Bolsheviks’ ideological basis had profound implications. For instance, the nationalization of industry and the redistribution of land were direct outcomes of their Marxist focus. However, the dictatorship of the proletariat also led to the suppression of dissent and the consolidation of power in the hands of the Communist Party. Critics argue that this centralization contradicted the spirit of proletarian governance, while supporters contend it was necessary to safeguard the revolution against counterrevolutionary forces. Regardless, the Bolsheviks’ commitment to Marxism reshaped Russia and influenced revolutionary movements worldwide, leaving a legacy of both inspiration and controversy.

Ancient Rome's Political Landscape: Did Parties Exist in the Republic?

You may want to see also

1917 Revolution Role: Bolsheviks led the October Revolution, overthrowing the Provisional Government under Lenin's leadership

Vladimir Lenin’s political party, the Bolsheviks, played a pivotal role in the 1917 October Revolution, a seismic event that reshaped Russian and global history. Founded as the majority faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1903, the Bolsheviks distinguished themselves through their commitment to a tightly organized, disciplined vanguard of professional revolutionaries. Unlike the Mensheviks, who favored a broader, more gradual approach to socialism, Lenin’s Bolsheviks advocated for immediate, radical change. This ideological clarity and organizational rigor positioned them to exploit the chaos of 1917, when Russia’s Provisional Government, established after the February Revolution, struggled to address war fatigue, economic collapse, and widespread discontent.

The Bolsheviks’ success in the October Revolution was not merely a product of Lenin’s leadership but also their strategic adaptability. Lenin’s return to Russia in April 1917, facilitated by Germany in a move to destabilize its wartime enemy, marked a turning point. His *April Theses* outlined a bold agenda: end the war, redistribute land to peasants, and transfer power to the soviets (workers’ and soldiers’ councils). This platform resonated with a war-weary population and positioned the Bolsheviks as the only party offering concrete solutions. Meanwhile, the Provisional Government’s failures—such as continuing the unpopular war and delaying land reform—eroded its legitimacy, creating a vacuum the Bolsheviks were poised to fill.

The October Revolution itself was a meticulously planned insurrection, not a spontaneous uprising. Lenin, operating from hiding after a failed July uprising, insisted on timing the revolt to coincide with the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, ensuring a veneer of legitimacy. On the night of October 24–25, Bolshevik-led Red Guards seized key points in Petrograd, including the Winter Palace, with minimal resistance. The Provisional Government’s collapse was swift, and by the next day, the Bolsheviks had declared themselves the new authority. This coup-like operation, though not universally supported, demonstrated the Bolsheviks’ ability to act decisively where others hesitated.

The aftermath of the revolution revealed both the Bolsheviks’ strengths and vulnerabilities. Lenin’s Decree on Peace, issued immediately, signaled Russia’s withdrawal from World War I, fulfilling a key promise. The Decree on Land transferred estates to peasants, solidifying rural support. However, these gains came at a cost: the Bolsheviks’ unilateral seizure of power alienated other socialist factions and set the stage for civil war. Their consolidation of power through the creation of the Cheka (secret police) and the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly in January 1918 underscored their willingness to prioritize control over democratic principles.

In retrospect, the Bolsheviks’ role in the October Revolution was a masterclass in political opportunism and ideological conviction. Lenin’s leadership transformed a marginalized faction into the architects of the world’s first socialist state. Yet, their methods—centralization, repression, and the rejection of power-sharing—laid the groundwork for the authoritarianism that would define the Soviet Union. The revolution’s legacy is thus complex: a testament to the power of revolutionary ideology, but also a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked power. For historians and political analysts, the Bolsheviks’ 1917 triumph remains a critical case study in how small, disciplined groups can exploit historical moments to achieve outsized influence.

Unveiling Your Political Journey: Share Your Unique Story and Beliefs

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Party Renaming: In 1918, Bolsheviks renamed themselves the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

The Bolsheviks' decision to rename themselves the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) in 1918 was a strategic move that reflected both ideological alignment and political pragmatism. By adopting the term "Communist," they explicitly tied their party to the global Marxist movement, signaling a commitment to revolutionary socialism and the dictatorship of the proletariat. This rebranding occurred during the tumultuous early years of the Russian Revolution, as the Bolsheviks sought to consolidate power and distinguish themselves from other socialist factions. The inclusion of "(Bolsheviks)" in the name served as a reminder of their historical roots, ensuring continuity with their pre-revolutionary identity while embracing a more universal ideological label.

Analytically, the renaming was a masterstroke in political branding. It allowed the Bolsheviks to position themselves as the vanguard of a global communist revolution, appealing to international socialist movements while solidifying domestic legitimacy. The shift from "Bolshevik" to "Communist" also helped to obscure internal divisions within the party, presenting a unified front during a period of intense civil war and economic crisis. This strategic rebranding underscored Lenin’s understanding of the power of language in shaping political narratives, as the new name carried both ideological weight and revolutionary fervor.

From a comparative perspective, the Bolsheviks’ renaming contrasts with other revolutionary movements that retained their original identities despite ideological shifts. For instance, the Chinese Communist Party never changed its name, even as its policies evolved significantly under leaders like Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. The Bolsheviks’ decision to rename themselves highlights their willingness to adapt their public image to suit the political moment, a flexibility that contributed to their survival and dominance in the early Soviet era.

Practically, the renaming had immediate implications for the party’s organizational structure and public outreach. It necessitated updates to official documents, propaganda materials, and international communications, ensuring that the new identity was consistently projected both domestically and abroad. For activists and members, the change required a shift in self-identification, reinforcing the party’s revolutionary mission and its role as the architect of a new socialist order. This rebranding was not merely symbolic; it was a tool for mobilizing support and legitimizing the Bolsheviks’ authority in a rapidly changing political landscape.

In conclusion, the Bolsheviks’ 1918 renaming to the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) was a calculated act of political rebranding that served multiple purposes. It aligned the party with global communism, strengthened its revolutionary credentials, and provided a cohesive identity during a period of instability. This move exemplifies Lenin’s strategic acumen and the Bolsheviks’ ability to harness language as a tool of power, leaving a lasting legacy in the history of political parties and revolutionary movements.

The Roaring Twenties: Republican Dominance in American Politics

You may want to see also

Lenin's Leadership: Lenin served as the party's leader until his death in 1924, shaping its policies

Vladimir Lenin's leadership of the Bolshevik Party, later renamed the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, was marked by his unwavering commitment to revolutionary Marxism and his ability to adapt its principles to the Russian context. From the party's rise to power in the 1917 October Revolution until his death in 1924, Lenin's influence was absolute. He was not merely a figurehead but the architect of the party's ideology, strategy, and tactics. His writings, such as *What Is to Be Done?* and *State and Revolution*, provided the theoretical foundation for the party's mission: to establish a dictatorship of the proletariat and transition to a socialist society.

Lenin's leadership style was both pragmatic and ruthless. He understood that revolution required discipline and organization, leading him to centralize power within the party. The creation of the Politburo and the secret police (Cheka) were direct outcomes of his belief in the necessity of a strong, centralized authority to safeguard the revolution. This approach, while effective in consolidating power, also sowed the seeds of authoritarianism that would characterize the Soviet Union for decades. Lenin's willingness to employ harsh measures, such as the Red Terror, underscores the lengths to which he was prepared to go to secure his vision.

One of Lenin's most significant contributions was his implementation of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921. Facing economic collapse and widespread famine after the Civil War, Lenin temporarily abandoned war communism in favor of a mixed economy. This policy allowed for limited private enterprise and market mechanisms, demonstrating his ability to adapt Marxist theory to practical realities. The NEP stabilized the economy and provided a breathing space for the new Soviet state, though it was later reversed by Stalin in favor of rapid industrialization.

Lenin's legacy as a leader is complex. On one hand, he was a visionary who successfully led a revolutionary movement to power and laid the groundwork for the world's first socialist state. On the other hand, his emphasis on party control and the use of force set a precedent for authoritarian governance. His leadership style and policies continue to be debated, but there is no denying his profound impact on the Bolshevik Party and the course of Russian and world history. To understand Lenin's leadership is to grapple with the contradictions of a man who sought to liberate the masses while simultaneously imposing a rigid, centralized system of control.

Political Parties and Conflict: Dynamics, Influence, and Societal Impact Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Lenin was a key founder and leader of the Bolshevik Party, which later became the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU).

Lenin was initially a member of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), where he later led the Bolshevik faction after the party split in 1903.

Lenin led the Bolshevik Party, which spearheaded the October Revolution of 1917 and established Soviet rule in Russia.