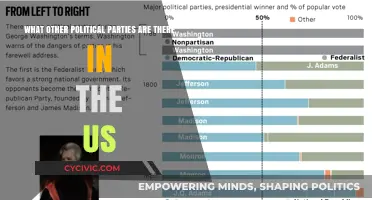

The 1920s in the United States, often referred to as the Roaring Twenties, were marked by significant economic growth, cultural dynamism, and political shifts. During this decade, the Republican Party dominated American politics, holding the presidency throughout the entire period with leaders such as Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. The GOP's dominance was underpinned by its pro-business policies, support for laissez-faire economics, and the widespread prosperity that many Americans experienced during this time. The party's appeal was further bolstered by its association with the era's social conservatism and its ability to capitalize on the public's desire for stability and normalcy after the upheavals of World War I and the Progressive Era. This Republican hegemony, however, would face challenges as the decade drew to a close, setting the stage for significant political realignments in the years to come.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Dominant Party | Republican Party |

| Presidents | Warren G. Harding (1921–1923), Calvin Coolidge (1923–1929), Herbert Hoover (1929–1933) |

| Key Policies | Laissez-faire economics, tax cuts for the wealthy, limited government intervention |

| Economic Focus | Business growth, industrialization, and consumerism |

| Social Climate | Conservatism, anti-immigration (e.g., Immigration Act of 1924), Prohibition (1920–1933) |

| Foreign Policy | Isolationism, reluctance to join the League of Nations |

| Cultural Era | The Roaring Twenties, marked by jazz, flappers, and cultural dynamism |

| Opposition Party | Democratic Party, largely marginalized during this period |

| End of Dominance | Great Depression (1929) led to a shift in political power in the 1930s |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Republican Party's Rise

The 1920s marked a significant shift in American political dominance, with the Republican Party rising to unprecedented power. This era, often referred to as the "Roaring Twenties," saw the GOP solidify its control over the presidency, Congress, and much of state governance. The party's success was rooted in its alignment with the decade's prevailing mood: prosperity, conservatism, and a retreat from the progressive reforms of the earlier 20th century. By championing policies that favored business growth, limited government intervention, and isolationism in foreign affairs, the Republicans tapped into the aspirations of a nation eager to embrace economic expansion and cultural modernity.

To understand the Republican Party's rise, consider its strategic appeal to key demographics. The GOP positioned itself as the party of prosperity, catering to industrialists, farmers, and middle-class Americans who benefited from the economic boom. For instance, President Calvin Coolidge's mantra, "The business of America is business," encapsulated the party's pro-corporate stance, which resonated with those enjoying the fruits of industrialization. Additionally, the Republicans' promise to maintain the status quo in social and racial policies attracted conservative voters wary of progressive changes. This alignment with the era's economic and social priorities created a broad coalition that sustained the party's dominance.

A critical factor in the Republican ascendancy was its ability to capitalize on the backlash against Woodrow Wilson's progressive agenda and the post-World War I disillusionment. The GOP framed itself as the antidote to Wilson's internationalism and government expansion, advocating for isolationism and reduced federal involvement in domestic affairs. The 1920 election of Warren G. Harding, who campaigned on a "return to normalcy," exemplified this shift. His administration, followed by Coolidge's, dismantled progressive-era regulations and slashed taxes, further entrenching Republican control by rewarding its core constituencies.

However, the party's rise was not without vulnerabilities. The GOP's close ties to big business and its neglect of labor and minority interests sowed seeds of discontent. The stock market crash of 1929 exposed the fragility of its economic policies, leading to the Great Depression and the eventual erosion of Republican dominance. Yet, during the 1920s, the party's strategic alignment with the decade's ethos ensured its unparalleled political supremacy. By studying this period, one gains insight into how a political party can harness the spirit of an era to achieve lasting power—a lesson in both strategy and timing.

Pepsi's Political Leanings: Uncovering the Brand's Party Affiliation

You may want to see also

Economic Policies & Prosperity

The 1920s, often referred to as the Roaring Twenties, were marked by unprecedented economic growth and prosperity in the United States. This era was dominated by the Republican Party, which held the presidency throughout the decade, first under Warren G. Harding and then under Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover. The Republicans’ economic policies, characterized by laissez-faire principles, tax cuts, and business-friendly regulations, are often credited with fueling this boom. However, the question remains: how did these policies contribute to prosperity, and what were their limitations?

At the heart of Republican economic policy during the 1920s was the belief in minimal government intervention. President Coolidge famously declared, “The business of America is business,” a mantra that guided his administration’s approach. One of the most significant measures was the Revenue Act of 1926, which slashed income tax rates for the wealthiest Americans from 25% to 20%. This move was intended to stimulate investment and consumer spending, and it succeeded in part. Industrial production surged, with sectors like automobiles and construction leading the way. For instance, automobile production nearly doubled between 1920 and 1929, thanks in part to Henry Ford’s assembly line innovations and the affordability of cars for the middle class. This growth created a ripple effect, generating jobs and boosting related industries such as steel and rubber.

However, the prosperity of the 1920s was not evenly distributed. While the wealthy and middle class thrived, farmers and unskilled workers often struggled. Agricultural prices plummeted due to overproduction, leaving many farmers in debt. Additionally, the focus on industrial growth and stock market speculation created an economic bubble. By 1929, the stock market had become wildly overvalued, with margin buying (purchasing stocks with borrowed money) reaching unsustainable levels. This imbalance set the stage for the Great Depression, which began with the stock market crash in October 1929. The Republicans’ hands-off approach, while effective in fostering short-term growth, failed to address underlying economic inequalities or regulate speculative excesses.

To understand the impact of these policies, consider the following practical takeaway: while tax cuts and deregulation can stimulate economic activity, they must be paired with measures to ensure broad-based prosperity. For example, investing in infrastructure, education, and social safety nets can help distribute wealth more equitably. In the 1920s, the absence of such policies left the economy vulnerable to collapse. Today, policymakers can learn from this era by balancing pro-business initiatives with safeguards to prevent systemic risks and ensure that growth benefits all segments of society.

In conclusion, the Republican-dominated economic policies of the 1920s fostered remarkable prosperity but were ultimately unsustainable. Their emphasis on tax cuts and deregulation drove industrial growth and consumer spending, yet they failed to address economic disparities or regulate speculative behavior. This duality serves as a cautionary tale: while laissez-faire principles can unleash economic potential, they require complementary measures to ensure stability and inclusivity. By studying this period, we gain valuable insights into the delicate balance between growth and equity in economic policymaking.

The Power of Political Rallies: Mobilizing Support and Shaping Public Opinion

You may want to see also

Teapot Dome Scandal

The 1920s in American politics were dominated by the Republican Party, which held the presidency for the entire decade under Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. This era, often referred to as the "Roaring Twenties," was marked by economic prosperity, cultural dynamism, and a general sense of optimism. However, beneath the surface of this gilded age lay corruption and scandal, the most notorious of which was the Teapot Dome Scandal. This scandal not only tarnished the reputation of the Republican administration but also exposed the vulnerabilities of unchecked executive power and the cozy relationship between government and big business.

The Teapot Dome Scandal centered on the secret leasing of federal oil reserves in Wyoming and California to private companies without competitive bidding. In 1922, Albert B. Fall, Secretary of the Interior under President Harding, orchestrated the leasing of these reserves to Pan American Petroleum and Transport Company (later acquired by Standard Oil of Indiana) and Mammoth Oil. In exchange, Fall received personal loans and gifts totaling approximately $400,000 (equivalent to over $6 million today). The scandal came to light in 1924, revealing a blatant abuse of public trust and a betrayal of the government’s responsibility to manage natural resources for the public good.

Analyzing the Teapot Dome Scandal offers a cautionary tale about the dangers of cronyism and the erosion of ethical standards in governance. Fall’s actions were not merely a personal failing but a symptom of a broader systemic issue: the lack of transparency and accountability in the Harding administration. The scandal also highlighted the need for stronger oversight mechanisms, as existing laws and regulations were insufficient to prevent such abuses. In response, Congress launched investigations, and Fall was convicted of bribery in 1929, becoming the first Cabinet secretary to be imprisoned for actions committed while in office.

From a comparative perspective, the Teapot Dome Scandal stands out as one of the most egregious examples of political corruption in the 20th century, rivaling even the Watergate scandal in terms of public outrage. Unlike Watergate, however, Teapot Dome did not involve a cover-up by the president himself, though Harding’s laissez-faire leadership style created an environment where such misconduct could flourish. The scandal also contrasts with other instances of corruption during the 1920s, such as the Ohio gang’s influence-peddling, in its direct impact on public resources and its long-lasting legal and political repercussions.

For those interested in understanding the implications of the Teapot Dome Scandal, a practical takeaway is the importance of vigilance in holding public officials accountable. Citizens and lawmakers alike must demand transparency in government dealings, particularly regarding the management of natural resources and public lands. Steps to prevent similar scandals include strengthening whistleblower protections, mandating competitive bidding for government contracts, and imposing stricter penalties for corruption. By learning from the mistakes of the past, we can work toward a more ethical and accountable political system.

Exploring Sexuality in Politics: Which Leaders Identify as LGBTQ+?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$21 $30

$8.93 $35

Immigration Restrictions

The 1920s in America were marked by a significant shift in immigration policy, driven by the Republican Party, which dominated both Congress and the presidency for most of the decade. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924, also known as the Johnson-Reed Act, were pivotal pieces of legislation that severely restricted immigration. These laws established a quota system that favored Northern and Western European immigrants while drastically limiting those from Southern and Eastern Europe, Asia, and Africa. The rationale behind these restrictions was rooted in nativist fears, economic concerns, and a desire to preserve the nation’s cultural homogeneity.

Analyzing the impact of these restrictions reveals a stark transformation in immigration patterns. Prior to the 1920s, the United States had experienced a wave of immigration from diverse regions, contributing to its cultural and economic growth. However, the new quotas reduced annual immigration from hundreds of thousands to a mere fraction of that number. For instance, while over 200,000 Italians were admitted annually in the early 1900s, the 1924 Act limited their quota to just 3,845 per year. This shift not only altered the demographic makeup of the country but also reinforced a hierarchy of desirability among immigrant groups, with those from Northern and Western Europe deemed more "American" than others.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these restrictions is crucial for historians and policymakers alike. The 1924 Act’s formula, based on the 1890 census, was designed to favor immigrants from countries with established populations in the U.S. before large-scale Southern and Eastern European immigration began. This method effectively froze the ethnic composition of the nation, reflecting the anxieties of a post-World War I society wary of change. For those studying immigration trends, this period serves as a case study in how policy can be wielded to shape national identity and exclude certain groups.

Persuasively, it’s worth noting that these restrictions were not without opposition. Labor unions, religious groups, and immigrant communities protested the quotas, arguing they were discriminatory and contradicted America’s self-proclaimed identity as a "nation of immigrants." Despite these efforts, the Republican-led Congress and President Calvin Coolidge championed the laws, reflecting the party’s alignment with nativist and protectionist sentiments. This era underscores the power of political dominance in shaping long-lasting policies that continue to influence immigration debates today.

In conclusion, the immigration restrictions of the 1920s were a defining feature of Republican dominance in American politics during the decade. By limiting immigration through quota systems, the party sought to address economic and cultural concerns, though at the cost of diversity and inclusivity. This period serves as a reminder of how political agendas can reshape societal norms and policies, leaving a legacy that persists in contemporary discussions on immigration. Understanding these restrictions provides valuable insights into the intersection of politics, identity, and policy-making.

South Africa's Political Violence: Unmasking Parties Linked to Aggression

You may want to see also

Isolationist Foreign Policy

The 1920s in America, often referred to as the Roaring Twenties, were marked by a dominant Republican Party that championed a policy of isolationism in foreign affairs. This era, following the devastation of World War I, saw the United States retreat from international entanglements, focusing instead on domestic prosperity and economic growth. The isolationist foreign policy of the 1920s was not merely a passive stance but a deliberate and calculated approach to global relations, shaped by the belief that America's interests were best served by avoiding foreign conflicts and concentrating on internal development.

The Roots of Isolationism

Isolationism in the 1920s was deeply rooted in historical and cultural factors. The trauma of World War I, which had cost the U.S. over 116,000 lives and billions of dollars, left a profound aversion to foreign intervention. The Republican Party, led by presidents Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover, capitalized on this sentiment. They argued that America’s role was not to police the world but to serve as a beacon of democracy and capitalism. This ideology was further reinforced by the passage of restrictive immigration laws, such as the Immigration Act of 1924, which limited the influx of foreigners and symbolized a broader desire to preserve American identity and resources.

Practical Manifestations of Isolationism

The isolationist policy manifested in several key areas. First, the U.S. refused to join the League of Nations, despite its role in its creation, fearing it would entangle the nation in European disputes. Second, the Washington Naval Conference of 1922, while promoting disarmament, also reflected America’s reluctance to commit to international alliances. Third, economic policies, such as the Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922, prioritized domestic industries by imposing high tariffs on foreign goods, further insulating the U.S. economy from global markets. These actions were not just political posturing but practical steps to ensure America’s independence in a turbulent world.

Critiques and Limitations

While isolationism provided a sense of security and allowed the U.S. to focus on its economic boom, it was not without criticism. Critics argued that this policy ignored global realities, such as the rise of fascism in Europe and the instability in Asia. By avoiding international commitments, the U.S. missed opportunities to shape global events and potentially prevent future conflicts. For instance, the refusal to participate in the League of Nations left a power vacuum that other nations, with less democratic ideals, were quick to fill. This shortsightedness would later be exposed during the Great Depression and the lead-up to World War II.

Lessons for Modern Policy

The isolationist foreign policy of the 1920s offers valuable lessons for contemporary global relations. While the desire to prioritize domestic issues is understandable, complete disengagement from international affairs can lead to unintended consequences. Modern policymakers must strike a balance between national interests and global responsibilities. For instance, instead of outright isolation, nations can adopt a policy of selective engagement, focusing on alliances and initiatives that align with their values and long-term goals. This approach ensures that countries remain relevant on the world stage while safeguarding their internal stability.

In conclusion, the isolationist foreign policy of the 1920s was a defining feature of Republican dominance during the era. It reflected the nation’s war-weariness and desire for prosperity but also highlighted the limitations of disengagement in an increasingly interconnected world. By studying this period, we gain insights into the complexities of balancing national interests with global obligations, a challenge that remains relevant today.

Understanding the Core Values and Beliefs of the Independent Political Party

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Republican Party dominated American politics during the 1920s, holding the presidency and controlling Congress for most of the decade.

The Republican presidents during the 1920s were Warren G. Harding (1921–1923), Calvin Coolidge (1923–1929), and Herbert Hoover (1929–1933), though Hoover's term extended into the 1930s.

The Republican Party dominated due to its association with economic prosperity, support for business interests, and the post-World War I backlash against progressivism and internationalism.

While Republicans dominated, Democrats maintained a presence, particularly in the South, but they were largely marginalized nationally due to internal divisions and the GOP's popularity.

The Great Depression, beginning in 1929, ended Republican dominance as voters blamed the party for the economic collapse, leading to Democratic gains in the 1930s under Franklin D. Roosevelt.