The political party most closely associated with bringing about Prohibition in the United States was the Republican Party, which, in alliance with the Progressive and temperance movements, championed the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act. While Prohibition had bipartisan support, Republicans, particularly those aligned with the drys, played a pivotal role in its passage, driven by moral, social, and public health concerns. The Anti-Saloon League, a powerful lobbying group, also heavily influenced Republican lawmakers, ensuring the legislation’s success in 1919, which took effect in 1920. However, the Democratic Party, though divided, also contributed to its enactment, reflecting the widespread but complex political and societal push for alcohol prohibition.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The Temperance Movement's Influence

The Temperance Movement, a social and political force advocating for reduced or eliminated alcohol consumption, played a pivotal role in the push for Prohibition in the United States. While the movement itself was not a political party, its influence was deeply intertwined with the political landscape, particularly with the Republican Party. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Temperance Movement had gained significant traction, leveraging moral, religious, and health arguments to sway public opinion and political agendas. This movement’s efforts culminated in the 18th Amendment, ratified in 1919, which banned the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages.

Analytically, the Temperance Movement’s success can be attributed to its strategic alignment with existing political factions. The Republican Party, in particular, saw an opportunity to appeal to rural, Protestant voters who were staunch supporters of Temperance. By incorporating anti-alcohol platforms into their campaigns, Republicans gained a competitive edge in elections. For instance, the Progressive wing of the Republican Party, which emphasized social reform and moral improvement, became a natural ally to Temperance advocates. This alliance was evident in the 1916 presidential election, where Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes ran on a platform that included support for Prohibition, though he ultimately lost to Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat who later signed the 18th Amendment into law.

Instructively, the Temperance Movement’s tactics offer valuable lessons for modern advocacy groups. They effectively utilized grassroots organizing, leveraging local churches, women’s groups, and community leaders to spread their message. For example, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), founded in 1874, became one of the most influential organizations, advocating not only for abstinence but also for women’s suffrage and labor rights. Their approach of combining moral persuasion with practical education—such as hosting lectures on the health effects of alcohol and distributing literature—created a broad-based movement that resonated across demographics. Modern campaigns can emulate this by focusing on local engagement, multi-issue advocacy, and evidence-based messaging.

Persuasively, the Temperance Movement’s legacy underscores the power of moral conviction in shaping policy. While Prohibition itself was ultimately repealed in 1933 due to widespread non-compliance and economic challenges, the movement’s impact on public health and social norms cannot be overlooked. For instance, alcohol consumption rates did decline during the Prohibition era, and the movement’s emphasis on the dangers of alcohol abuse contributed to long-term shifts in drinking culture. Today, public health campaigns against smoking and opioid use often draw on similar strategies, framing their causes as moral imperatives backed by scientific evidence. This historical precedent demonstrates that sustained advocacy, even if it doesn’t achieve its original goals, can leave a lasting imprint on society.

Comparatively, the Temperance Movement’s relationship with the Republican Party highlights the complexities of aligning social movements with political parties. While the Republicans benefited from Temperance support, the movement itself was not monolithic, and its members spanned the political spectrum. Democrats, particularly in the South, also had factions that supported Prohibition, though the issue was less central to their platform. This dynamic illustrates the risks of over-reliance on a single party, as the movement’s success became tied to the fortunes of the Republicans. For contemporary movements, this serves as a cautionary tale: while political alliances are necessary, maintaining a broad coalition can ensure resilience and long-term influence.

Understanding Political Party Coalitions: Formation, Function, and Impact

You may want to see also

Role of the Republican Party

The Republican Party played a pivotal role in the enactment of Prohibition in the United States, a fact often overshadowed by broader narratives of the temperance movement. While Prohibition was a bipartisan effort, the Republican Party’s alignment with Progressive Era reforms and its strategic political calculations were instrumental in pushing the 18th Amendment through Congress and securing its ratification in 1919. This alignment was not merely ideological but also a tactical move to appeal to rural, Protestant, and middle-class voters who saw alcohol as a societal vice.

Analytically, the Republican Party’s support for Prohibition can be traced to its coalition-building strategies in the early 20th century. By championing the cause of the Anti-Saloon League, a powerful lobbying group, Republicans aimed to consolidate support from women, religious conservatives, and rural communities. This was particularly evident in the 1916 presidential election, where Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes campaigned on a platform that included support for Prohibition. Although Hughes lost the election, the Republican-controlled Congress passed the 18th Amendment in 1917, setting the stage for its ratification two years later. This demonstrates how the party leveraged the issue to strengthen its political base.

Instructively, understanding the Republican Party’s role requires examining its internal divisions. Not all Republicans were enthusiastic supporters of Prohibition. Urban Republicans, particularly those in industrial cities with large immigrant populations, often opposed the ban on alcohol, recognizing its potential to alienate voters who viewed such measures as an infringement on personal freedom. However, party leadership prioritized unity and the broader Progressive agenda, which included not only Prohibition but also women’s suffrage and labor reforms. This internal compromise highlights the party’s strategic calculus in advancing Prohibition despite dissenting voices.

Persuasively, the Republican Party’s legacy in Prohibition remains a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of moral legislation. While the 18th Amendment was intended to reduce crime, poverty, and social ills, it instead fueled organized crime, created a black market for alcohol, and eroded public trust in government. The party’s association with Prohibition ultimately became a political liability, particularly during the Great Depression, when economic concerns overshadowed moral crusades. This underscores the risks of prioritizing ideological purity over practical governance, a lesson relevant to modern policy debates.

Comparatively, the Republican Party’s role in Prohibition contrasts sharply with its later stance on government intervention. In the decades following the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, the party increasingly embraced laissez-faire economics and individual liberty, distancing itself from the regulatory zeal of the Progressive Era. This shift reflects the evolving nature of the Republican Party and its adaptability to changing societal values. Yet, the Prohibition era remains a defining chapter in the party’s history, illustrating its capacity to mobilize around controversial issues and shape national policy.

Nazism's Political Doctrine: Unraveling the Ideology Behind Hitler's Regime

You may want to see also

Progressive Era Politics

The Progressive Era, spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was a period of significant social and political reform in the United States. Central to this era was the push for Prohibition, a movement driven by a coalition of reformers, religious groups, and politicians. While no single political party can claim sole responsibility for Prohibition, the Republican Party played a pivotal role in its enactment, particularly through its alignment with Progressive ideals. The 18th Amendment, which established Prohibition in 1920, was championed by Republicans like President Herbert Hoover, who saw it as a moral and social imperative. However, the Democratic Party also supported the measure, reflecting the bipartisan nature of the temperance movement.

Analyzing the political landscape, the Progressive Era was marked by a shift toward government intervention to address societal issues, including alcohol consumption. Progressives believed that banning alcohol would reduce crime, poverty, and domestic violence, aligning with their broader goals of efficiency, morality, and social welfare. The Anti-Saloon League, a non-partisan but influential organization, strategically allied with politicians from both parties to advance Prohibition. This cross-party collaboration underscores the complexity of attributing Prohibition to a single political entity. Yet, Republicans, particularly in the Midwest and rural areas, were more vocal in their support, leveraging the issue to appeal to their conservative and religious base.

Instructively, the path to Prohibition involved a series of legislative steps and public campaigns. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and other advocacy groups mobilized grassroots efforts, while politicians introduced bills at the state and federal levels. By 1917, 26 states had already enacted prohibition laws, creating momentum for the 18th Amendment. The process highlights the importance of coalition-building and sustained advocacy in achieving policy change. For modern reformers, this serves as a lesson in leveraging both public sentiment and legislative strategy to drive transformative initiatives.

Comparatively, Prohibition stands out as both a triumph and a cautionary tale in Progressive Era politics. While it reflected the era’s idealism and commitment to social reform, its enforcement proved challenging, leading to widespread bootlegging and organized crime. This paradox illustrates the tension between Progressive goals and practical realities. Unlike other reforms, such as antitrust legislation or labor protections, Prohibition’s failure ultimately led to its repeal in 1933. This contrast underscores the need for policymakers to balance moral imperatives with feasible implementation strategies.

Descriptively, the Progressive Era’s politics were characterized by a blend of optimism and activism. Reformers saw Prohibition as a means to purify society, mirroring their efforts to combat corruption, improve public health, and enhance civic life. The era’s political leaders, from Theodore Roosevelt to Jane Addams, embodied this spirit, advocating for systemic change. Prohibition, in this context, was not just a policy but a symbol of the Progressive movement’s ambition to reshape American society. Its legacy reminds us of the enduring power—and limitations—of political idealism.

Unveiling Claire's Political Affiliation: Which Party Does She Support?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Anti-Saloon League's Campaign

The Anti-Saloon League (ASL), founded in 1893, was a pivotal force in the temperance movement, but its success in bringing about Prohibition was not merely a matter of moral persuasion. It was a masterclass in political strategy, leveraging grassroots organizing, lobbying, and cross-party alliances to achieve its goal. Unlike many single-issue groups, the ASL did not align itself exclusively with one political party. Instead, it adopted a pragmatic approach, working with Republicans, Democrats, and Progressives alike, wherever it found common ground on the issue of alcohol prohibition.

Consider the ASL’s tactical brilliance: it focused on local and state-level politics first, securing dry laws in individual states to build momentum for a national ban. By 1916, 23 states had already enacted prohibition laws, creating a critical mass that pressured federal lawmakers. The ASL’s leader, Wayne Wheeler, was a shrewd operator who targeted politicians’ vulnerabilities, often threatening to mobilize voters against them if they opposed temperance measures. This strategy was particularly effective in the 1916 elections, where the ASL’s influence helped tip the balance in key races, paving the way for the 18th Amendment’s passage in 1919.

What set the ASL apart was its ability to frame Prohibition as a solution to broader societal problems. It linked alcohol consumption to issues like domestic violence, poverty, and industrial accidents, appealing to a wide range of voters, including women, labor activists, and religious groups. For instance, the ASL distributed pamphlets claiming that alcohol was responsible for 50% of industrial accidents, a statistic that resonated with workers and employers alike. This messaging was not just moralistic but practical, positioning Prohibition as a progressive reform rather than a religious crusade.

However, the ASL’s success was not without controversy. Its single-minded focus on Prohibition often came at the expense of other social issues, and its tactics could be heavy-handed. Critics accused the league of manipulating public opinion and strong-arming politicians. Moreover, the ASL’s alliance with the Republican Party in the 1920s, particularly during the Harding and Coolidge administrations, alienated Democrats and contributed to the eventual backlash against Prohibition. By 1933, the movement’s overreach and the rise of organized crime led to the repeal of the 18th Amendment, marking a cautionary tale about the limits of single-issue politics.

In practical terms, the ASL’s campaign offers valuable lessons for modern advocacy groups. First, build a broad coalition by framing your issue as a solution to multiple problems. Second, focus on incremental victories at the local level to create momentum for national change. Finally, be mindful of the risks of overreach; single-issue campaigns can achieve remarkable successes, but they must adapt to shifting public sentiment to avoid backlash. The Anti-Saloon League’s rise and fall remain a fascinating study in the power—and peril—of focused political activism.

Unveiling Walt Disney's Political Party Affiliation: A Historical Perspective

You may want to see also

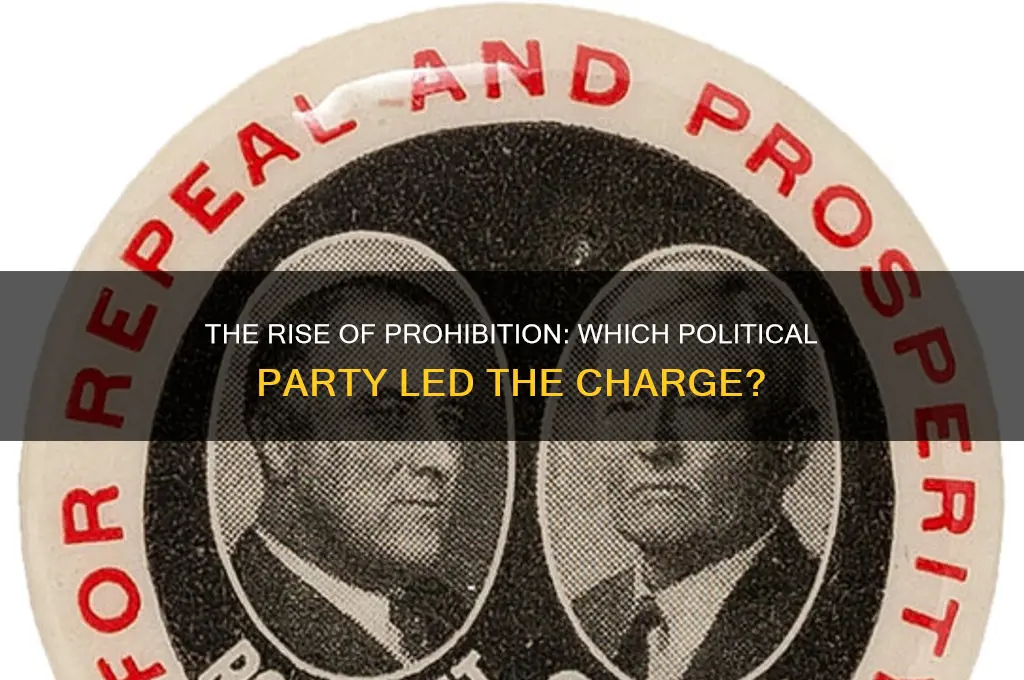

18th Amendment Passage

The 18th Amendment, which ushered in Prohibition in the United States, was the culmination of decades of advocacy by the temperance movement, a coalition dominated by religious and progressive reformers. While no single political party can claim sole responsibility, the Republican Party played a pivotal role in its passage. Republicans, particularly those aligned with the Progressive wing, saw Prohibition as a solution to societal ills like domestic violence, poverty, and industrial inefficiency, often attributed to alcohol abuse. Their support was instrumental in pushing the amendment through Congress in 1917, where it was approved by a two-thirds majority in both the House and Senate, and later ratified by the required three-fourths of state legislatures in 1919.

Analyzing the political landscape of the early 20th century reveals why Republicans took the lead. The party’s base included many Protestant voters who viewed alcohol as a moral and social evil. Additionally, Progressive Republicans, such as President Woodrow Wilson, supported Prohibition as part of a broader reform agenda aimed at improving public health and morality. Democrats, while not uniformly opposed, were less cohesive on the issue, with Southern Democrats often resisting federal intervention in what they saw as a states’ rights matter. This partisan dynamic highlights how the Republican Party’s ideological alignment with temperance advocates made them the driving force behind the 18th Amendment.

The passage of the 18th Amendment also underscores the power of grassroots movements in shaping legislation. The Anti-Saloon League, a nonpartisan but predominantly Republican-aligned organization, employed sophisticated lobbying tactics to pressure lawmakers. They targeted elections, endorsing candidates who supported Prohibition and opposing those who did not, effectively making it a political liability to oppose the amendment. This strategy, combined with the moral fervor of the temperance movement, created an environment where even reluctant politicians felt compelled to vote in favor of Prohibition.

However, the 18th Amendment’s passage was not without controversy. Critics argued it was an overreach of federal power and a violation of personal liberty. The amendment’s enforcement, codified in the Volstead Act, proved difficult and led to widespread bootlegging, organized crime, and public defiance. These unintended consequences ultimately undermined the amendment’s goals and set the stage for its repeal in 1933 with the 21st Amendment. This cautionary tale illustrates the risks of legislating morality and the importance of considering practical implications alongside ideological aims.

In conclusion, while the 18th Amendment was a bipartisan effort, the Republican Party’s alignment with the temperance movement and its strategic political maneuvering were crucial to its passage. The amendment’s history serves as a reminder of how moral and ideological convictions can drive legislative change, but also of the potential pitfalls when such changes are not grounded in practical realities. Understanding this chapter in American history offers valuable insights into the interplay between politics, morality, and governance.

Exploring Global Political Party Objectives: Ideologies, Strategies, and Goals

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Republican Party was the primary political force behind the passage of Prohibition, officially enacted through the 18th Amendment in 1920.

While some Democrats supported Prohibition, the party was divided on the issue. Many Southern Democrats backed it, but urban Democrats often opposed it, making the Republican Party the main driver of the movement.

Yes, the temperance movement, led by groups like the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Anti-Saloon League, played a significant role. These groups were non-partisan but heavily influenced Republican lawmakers.

While Prohibition ultimately passed with votes from both parties, the Republican Party was more unified in its support. The 18th Amendment was ratified by state legislatures, many of which were Republican-controlled at the time.