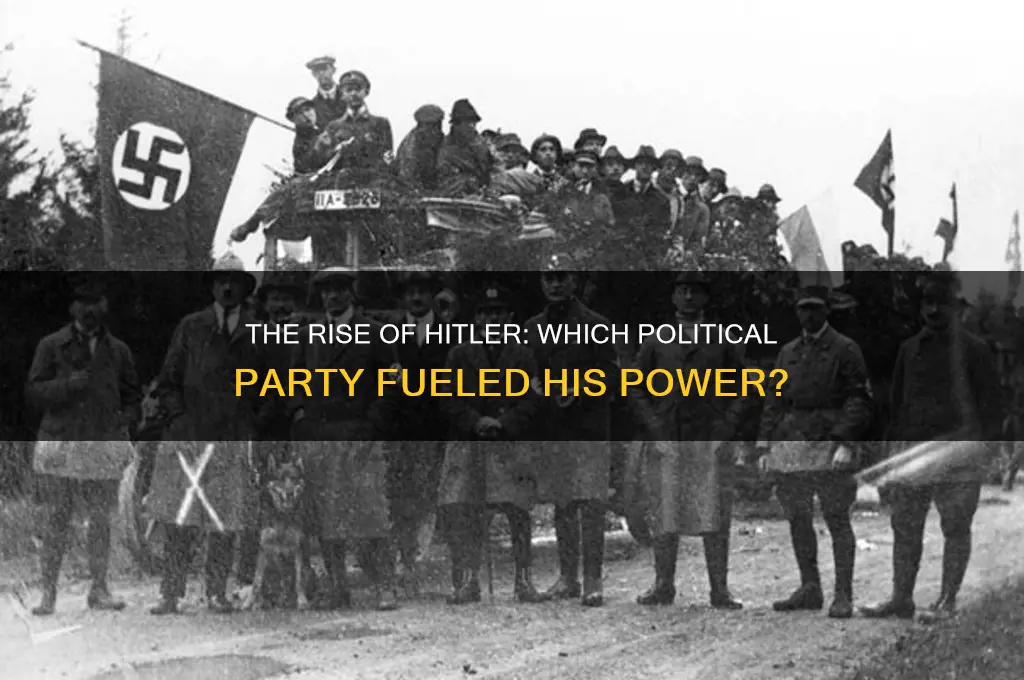

The political party that brought Adolf Hitler to power was the National Socialist German Workers' Party, commonly known as the Nazi Party. Founded in 1919, the party initially struggled to gain traction in Germany's tumultuous post-World War I landscape. However, under Hitler's charismatic leadership and through a combination of nationalist rhetoric, anti-Semitic propaganda, and promises of economic revival, the Nazis rapidly gained popularity during the early 1930s. The party exploited widespread discontent over the Treaty of Versailles, hyperinflation, and political instability, culminating in Hitler's appointment as Chancellor in 1933. This marked the beginning of the Nazi regime, which would lead Germany into World War II and perpetrate the Holocaust, leaving an indelible and horrific mark on history.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) |

| Common Name | Nazi Party |

| Founded | 1920 (as German Workers' Party, renamed NSDAP in 1921) |

| Ideology | Nazism (Fascism, Ultranationalism, Antisemitism, Racialism) |

| Leader | Adolf Hitler (1921–1945) |

| Symbol | Swastika (Hakenkreuz) |

| Colors | Red, White, Black |

| Headquarters | Munich, Germany |

| Peak Membership | Approximately 8.5 million (1945) |

| Political Position | Far-right |

| Key Policies | Totalitarianism, Racial Purity, Expansionism, Anti-Communism |

| Notable Figures | Hermann Göring, Joseph Goebbels, Heinrich Himmler |

| Rise to Power | 1933 (Hitler appointed Chancellor) |

| End | 1945 (Dissolved after Germany's defeat in WWII) |

| Legacy | Associated with the Holocaust, WWII, and widespread human rights violations |

Explore related products

$28.95 $28.95

What You'll Learn

- Rise of the Nazi Party: Hitler joined and later led the National Socialist German Workers' Party

- Post-WWI Germany: Economic crisis and nationalism fueled support for extremist parties like the Nazis

- Hitler's Leadership: His charisma and rhetoric transformed the Nazi Party into a dominant political force

- Election Victory: The Nazis gained parliamentary majority, enabling Hitler's appointment as Chancellor

- Enabling Act (1933): This law granted Hitler dictatorial powers, solidifying Nazi control over Germany

Rise of the Nazi Party: Hitler joined and later led the National Socialist German Workers' Party

Adolf Hitler’s ascent to power was inextricably tied to the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party. Founded in 1919, the party initially languished as a fringe group in the turbulent aftermath of World War I. Hitler joined in 1919, drawn by its nationalist and anti-Semitic rhetoric, and quickly rose through its ranks. By 1921, he had assumed leadership, transforming the NSDAP into a vehicle for his extremist ideology. This period marked the beginning of a calculated strategy to exploit Germany’s economic despair, political instability, and widespread resentment toward the Treaty of Versailles.

Hitler’s leadership style was both charismatic and ruthless. He rebranded the party with a mix of populist appeals and militaristic symbolism, including the swastika and the Sturmabteilung (SA), the party’s paramilitary wing. The NSDAP’s platform, though vague, promised national revival, racial purity, and the dismantling of the Weimar Republic’s democratic institutions. Hitler’s oratory skills and ability to channel public anger into a singular, scapegoating narrative—targeting Jews, communists, and other minorities—resonated deeply with a disillusioned populace. The Beer Hall Putsch of 1923, though a failure, cemented Hitler’s status as a martyr for the cause and provided him with a platform to refine his tactics during his subsequent imprisonment.

The Great Depression of the early 1930s created the perfect storm for the Nazi Party’s rise. Unemployment soared, and the Weimar government’s inability to address the crisis eroded public trust. Hitler’s simplistic solutions—blaming external forces and promising prosperity through authoritarian control—gained traction. The NSDAP’s electoral success in 1932, becoming the largest party in the Reichstag, positioned Hitler to be appointed Chancellor in January 1933. Within months, he exploited the Reichstag fire to consolidate power, eliminating political opponents and establishing a dictatorship under the guise of national emergency.

The Nazi Party’s rise was not merely a product of Hitler’s charisma but also of strategic manipulation of institutional weaknesses. By infiltrating local governments, controlling media narratives, and fostering a cult of personality, the NSDAP created an illusion of inevitability around Hitler’s leadership. The Enabling Act of 1933 formally granted him dictatorial powers, marking the end of democracy in Germany. This transformation from a marginal group to the dominant force in German politics underscores the dangerous interplay between extremist ideology, societal vulnerability, and the erosion of democratic safeguards.

Understanding the Nazi Party’s rise offers a cautionary tale about the fragility of democratic institutions and the allure of authoritarian solutions during times of crisis. Hitler’s ability to exploit fear, nationalism, and economic despair remains a stark reminder of the importance of vigilance against extremist ideologies. The NSDAP’s trajectory serves as a historical case study in how a single individual, backed by a radical party, can dismantle a nation’s freedoms and plunge the world into catastrophe.

KKK's Political Ties: Uncovering the Party's Historical Affiliation

You may want to see also

Post-WWI Germany: Economic crisis and nationalism fueled support for extremist parties like the Nazis

The Treaty of Versailles, signed in 1919, imposed crippling reparations on Germany, estimated at 132 billion gold marks, a sum economists deemed unpayable without devastating economic consequences. This financial burden, coupled with the loss of territories and resources, plunged Germany into a severe economic crisis. Hyperinflation, peaking in 1923, rendered the German mark virtually worthless, erasing savings and leaving millions destitute. Factories shuttered, unemployment soared to nearly 30%, and widespread hunger became a grim reality. This economic despair created fertile ground for extremist ideologies, as desperate citizens sought radical solutions to their suffering.

Amidst this chaos, nationalism surged as a potent force, fueled by resentment over the perceived humiliation of the Treaty of Versailles and the belief that Germany had been "stabbed in the back" by internal forces during the war. The Nazi Party, led by Adolf Hitler, exploited this sentiment masterfully. Hitler’s rhetoric of national revival, racial superiority, and the promise of restoring Germany to its former glory resonated deeply with a population yearning for pride and stability. The Nazis’ use of propaganda, mass rallies, and scapegoating of minorities, particularly Jews, tapped into the collective anger and fear of the German people, positioning themselves as the saviors of a broken nation.

The Weimar Republic’s political instability further aided the Nazis’ rise. Frequent changes in government, coalition infighting, and the failure to address the economic crisis eroded public trust in democracy. The Nazis capitalized on this disillusionment, presenting themselves as a strong, unified alternative to the chaos of parliamentary politics. By 1932, they had become the largest party in the Reichstag, and in 1933, Hitler was appointed Chancellor, marking the beginning of Nazi dictatorship.

To understand this period, consider the interplay of economic desperation and nationalist fervor. The economic crisis stripped away hope, while nationalism provided a sense of purpose and identity. The Nazis did not merely exploit these conditions; they amplified them, turning despair into a weapon and nationalism into a rallying cry. This toxic combination transformed a fringe extremist group into a dominant political force, with catastrophic consequences for Germany and the world.

Practical takeaways from this historical lesson include the importance of addressing economic inequality and fostering inclusive national identities. Societies must guard against the allure of simplistic, extremist solutions during times of crisis. By studying post-WWI Germany, we learn that economic stability and democratic resilience are not just economic or political issues—they are moral imperatives essential for preventing the rise of tyranny.

Zach Bryan's Political Affiliation: Uncovering His Party Preferences

You may want to see also

Hitler's Leadership: His charisma and rhetoric transformed the Nazi Party into a dominant political force

Adolf Hitler's rise to power was not merely a product of historical circumstance but a testament to his unparalleled ability to captivate and manipulate through charisma and rhetoric. The Nazi Party, initially a fringe group in the tumultuous post-World War I Germany, became a dominant political force largely due to Hitler's leadership. His speeches, laden with emotion and grand promises, resonated deeply with a nation grappling with economic collapse, national humiliation, and social unrest. By framing himself as the savior of Germany, Hitler transformed the Nazi Party from a marginal entity into a movement that commanded mass loyalty and fear.

Consider the mechanics of Hitler's rhetoric. He employed simple, repetitive language that was easy to understand yet powerful in its delivery. Phrases like "Germany above all" and "One people, one nation, one leader" tapped into the collective psyche of a wounded nation. His speeches were not just words but performances, complete with dramatic pauses, gesticulations, and a commanding presence that left audiences spellbound. This theatrical approach was deliberate, designed to evoke strong emotional responses and foster a cult of personality around him. For instance, his use of the term "Lebensraum" (living space) was not just a policy but a rallying cry that promised a return to greatness, appealing to both national pride and personal aspirations.

Hitler's charisma was equally instrumental in his leadership. He possessed an uncanny ability to connect with people across social strata, from disillusioned workers to disillusioned elites. His image as a self-made man who had risen from obscurity to lead a nation inspired millions. He cultivated an aura of invincibility, often appearing in military uniforms or delivering speeches from elevated platforms to emphasize his authority. This carefully crafted persona was reinforced by Nazi propaganda, which portrayed him as a messianic figure destined to restore Germany's glory. The result was a following that was not just political but quasi-religious, with Hitler at its center.

However, charisma and rhetoric alone cannot explain the Nazi Party's dominance. Hitler's leadership was also strategic, leveraging the party's organizational structure to consolidate power. He centralized authority, eliminating internal rivals and ensuring absolute loyalty. The SA (Stormtroopers) and later the SS became instruments of intimidation and control, suppressing opposition and enforcing Nazi ideology. Simultaneously, he exploited Germany's democratic institutions, using legal means to dismantle democracy from within. The Enabling Act of 1933, passed with the support of other parties, granted him dictatorial powers, marking the final step in the Nazi Party's transformation into the sole political force in Germany.

In conclusion, Hitler's leadership was a masterclass in the manipulation of human psychology and political systems. His charisma and rhetoric were not mere tools but weapons that reshaped the Nazi Party and, ultimately, the course of history. Understanding this dynamic is crucial, not just as a historical lesson but as a cautionary tale about the power of persuasive leadership in times of crisis. It underscores the importance of critical thinking and vigilance in safeguarding democratic values against demagoguery.

Peter A. Rubino's Political Party Affiliation Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

1933 Election Victory: The Nazis gained parliamentary majority, enabling Hitler's appointment as Chancellor

The 1933 German federal election marked a turning point in history, as it was the catalyst that propelled Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party into power. This election, held on March 5th, 1933, just a month after the Reichstag fire, saw the Nazis secure a significant victory, gaining a parliamentary majority that would alter the course of Germany and the world. The Nazis' rise to power was not merely a political shift but a dramatic transformation with far-reaching consequences.

The Election's Strategic Timing

The timing of this election was crucial. In the wake of the Reichstag fire, an event still shrouded in mystery and conspiracy theories, the Nazi government under President Paul von Hindenburg exploited the situation. They used the fire as a pretext to convince Hindenburg to invoke the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended civil liberties and granted the government emergency powers. This decree created an atmosphere of fear and repression, influencing the election's outcome. The Nazis' ability to manipulate events and public sentiment was a key factor in their success.

A Majority Secured

On election day, the Nazi Party, officially known as the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), won 43.9% of the votes, translating to 288 seats in the Reichstag. This was a substantial increase from the 37.3% they had secured in the previous election in November 1932. The Nazis' parliamentary majority was further solidified through their coalition with the German National People's Party (DNVP), giving them a combined total of 340 seats out of 647. This majority was pivotal, as it allowed Hitler to be appointed Chancellor, a position he would use to consolidate power and establish a dictatorship.

Hitler's Appointment and Its Impact

Adolf Hitler's appointment as Chancellor on January 30, 1933, was a direct result of the Nazis' electoral victory. This appointment marked the beginning of the end of the Weimar Republic and the rise of Nazi Germany. With the Chancellorship, Hitler quickly moved to consolidate power. He persuaded President Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag, calling for new elections in March, which were held under conditions heavily favoring the Nazis. The subsequent Enabling Act, passed in March 1933, granted Hitler dictatorial powers, effectively ending democracy in Germany. This series of events highlights the critical role the 1933 election played in Hitler's ascent.

A Cautionary Tale

The 1933 election victory of the Nazis serves as a stark reminder of the fragility of democracy and the importance of safeguarding it. It demonstrates how a combination of strategic timing, manipulation of public fear, and the exploitation of political institutions can lead to the rise of authoritarian regimes. This historical event underscores the need for constant vigilance in protecting democratic values and institutions, ensuring that the will of the majority does not become a tool for oppression. Understanding this chapter in history is essential to recognizing the signs of democratic erosion and taking preventive measures.

Thomas Jefferson's Stance on Political Parties: A Historical Perspective

You may want to see also

Enabling Act (1933): This law granted Hitler dictatorial powers, solidifying Nazi control over Germany

The Enabling Act of 1933 stands as a pivotal moment in history, marking the legal consolidation of Adolf Hitler’s dictatorial powers. Passed on March 23, 1933, this law effectively dismantled Germany’s democratic framework by granting the Nazi government the authority to enact laws without parliamentary consent. It was the Nazi Party (National Socialist German Workers' Party) that orchestrated this legislative coup, leveraging the Reichstag fire—a convenient crisis—to stoke fear and justify the act’s necessity. By framing it as a measure to protect the nation from chaos, the Nazis secured the two-thirds majority required for its passage, despite opposition from the Social Democrats, the only party to vote against it.

To understand the Enabling Act’s significance, consider its mechanics. It suspended constitutional rights, allowing Hitler’s cabinet to rule by decree for four years. This meant that the Nazis could bypass the Reichstag and the President, eliminating checks and balances. The act’s passage was not merely a procedural shift but a fundamental transformation of power. It turned Hitler from a chancellor into a dictator, with the authority to reshape Germany’s legal, political, and social landscape without restraint. This was the moment the Nazi Party’s ideological agenda became unstoppable, setting the stage for the Third Reich’s rise.

A comparative analysis reveals the Enabling Act’s uniqueness in modern history. Unlike other authoritarian regimes that seized power through overt coups or revolutions, the Nazis used legal means to dismantle democracy. This strategy, often termed “constitutional dictatorship,” relied on exploiting existing institutions to achieve totalitarian control. The act’s passage highlights the fragility of democratic systems when faced with determined, ideologically driven parties. It serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of granting unchecked power, even under the guise of emergency or stability.

For those studying political history or seeking to prevent such outcomes, the Enabling Act offers practical lessons. First, recognize the importance of safeguarding legislative independence and judicial oversight. Second, remain vigilant against the manipulation of crises to justify power grabs. Finally, understand that democratic erosion often occurs incrementally, through seemingly legitimate processes. By examining the Enabling Act, we gain insight into how a single law can alter the course of a nation—and how critical it is to defend democratic principles against authoritarian encroachment.

How Election Methods Shape Parties and Political Landscapes

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The National Socialist German Workers' Party, commonly known as the Nazi Party, brought Adolf Hitler to power.

The Nazi Party gained control of Germany in 1933, when Hitler was appointed Chancellor, and solidified its power through the Enabling Act later that year.

The Nazi Party served as the political vehicle for Hitler's ideology, mobilizing mass support through propaganda, nationalism, and promises to restore Germany's greatness after World War I.

The Nazi Party's ideology, centered on extreme nationalism, antisemitism, and authoritarianism, resonated with many Germans disillusioned by economic hardship and political instability, enabling Hitler's rise.

![Hitler: The Rise of Evil (UK) ( Hitler The Rise of Evil ) ( Hitler: La naissance du mal ) [ NON-USA FORMAT, PAL, Reg.2 Import - United Kingdom ]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81I-0Pi2kxS._AC_UY218_.jpg)