Economists, as a group, do not align uniformly with a single political party, as their views are shaped by diverse methodologies, theoretical frameworks, and empirical evidence rather than partisan ideology. While some economists may lean toward parties that emphasize free markets and limited government intervention, such as conservative or libertarian parties, others may support parties advocating for progressive taxation, social welfare programs, or environmental regulation, aligning more with liberal or social democratic platforms. The political affiliations of economists often reflect their specific areas of expertise, personal values, and interpretations of economic data, making their political leanings as varied as the field itself. Ultimately, economists prioritize evidence-based analysis over party loyalty, contributing to a wide spectrum of political perspectives within the profession.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Economists' Political Affiliations: Examining economists' personal political party preferences and their impact on research

- Policy Influence: How economists shape party platforms and influence government policies

- Ideological Leanings: Analyzing economists' alignment with conservative, liberal, or centrist political ideologies

- Party Endorsements: Instances of economists publicly supporting or advising specific political parties

- Non-Partisan Roles: Economists' efforts to remain politically neutral in academic and advisory roles

Economists' Political Affiliations: Examining economists' personal political party preferences and their impact on research

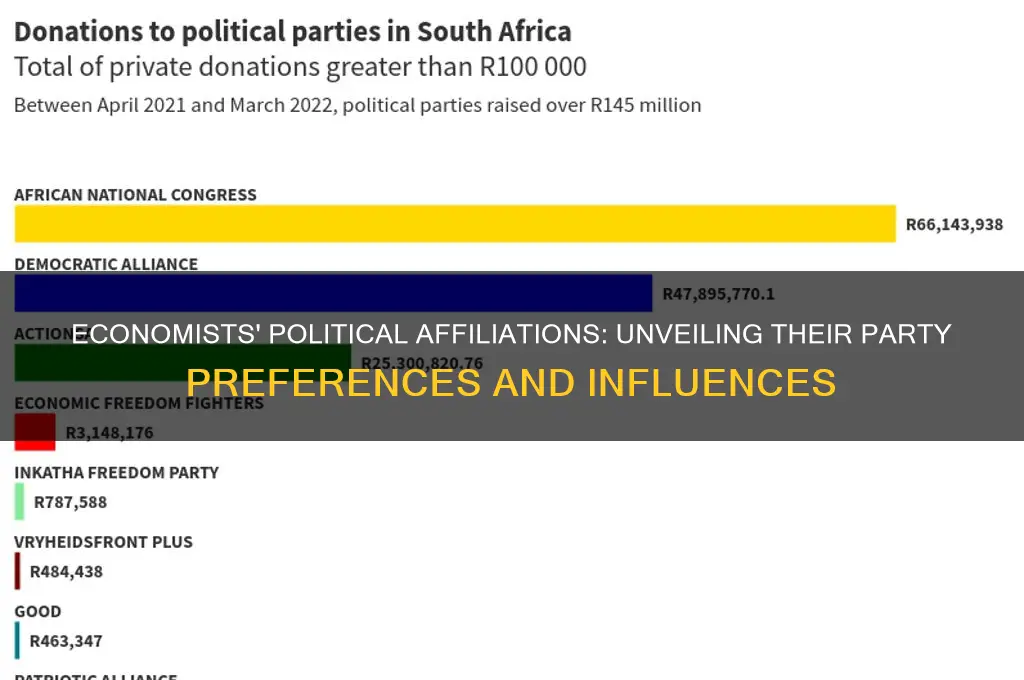

Economists, often perceived as neutral arbiters of data, are not immune to political leanings. Surveys reveal a pronounced leftward tilt among academic economists, with a majority identifying as Democrats or leaning Democratic in the U.S. context. For instance, a 2016 study by the Initiative on Global Markets found that 58% of economists identified as Democrats, compared to only 12% as Republicans. This imbalance raises questions about the objectivity of economic research and whether personal political affiliations subtly shape methodologies, interpretations, or policy recommendations.

This ideological skew isn’t confined to party labels. Economists’ policy preferences often align with progressive agendas, favoring government intervention in areas like healthcare, education, and climate change. For example, a 2020 survey by the National Association for Business Economics showed that 74% of economists supported a carbon tax, a policy more commonly championed by Democratic politicians. Such alignment suggests that personal politics may influence not just research topics but also the solutions economists propose, potentially limiting the exploration of alternative, market-based approaches.

However, the impact of political affiliation on research isn’t always overt. Economists pride themselves on empirical rigor, and peer review systems are designed to weed out bias. Yet, subtle influences can seep in through framing, data selection, or the emphasis placed on certain findings. For instance, a researcher’s political leanings might lead them to highlight income inequality over economic growth, or to downplay the unintended consequences of regulation. These choices, while not necessarily partisan, can reflect underlying ideological priorities.

To mitigate these risks, economists must adopt transparency and humility. Disclosing political affiliations in research, while not standard practice, could provide readers with context for interpreting findings. Additionally, interdisciplinary collaboration and diverse research teams can help balance perspectives, ensuring that studies are robust and less prone to ideological blind spots. Ultimately, acknowledging the role of personal politics in research isn’t about questioning economists’ integrity but about strengthening the credibility and relevance of their work in an increasingly polarized world.

Which Political Party Held Power During Key Historical Events?

You may want to see also

Policy Influence: How economists shape party platforms and influence government policies

Economists are not confined to ivory towers; their ideas permeate the political arena, shaping party platforms and government policies in profound ways. Consider the 2008 financial crisis. Economists like Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz advocated for stimulus spending and financial regulation, influencing Democratic Party policies under President Obama. Conversely, economists associated with the Chicago School, such as Eugene Fama, promoted free-market solutions, aligning with Republican platforms. This illustrates how economists, through their research and advocacy, become architects of policy frameworks, often determining the direction of economic governance.

To understand their influence, examine the role of think tanks and advisory bodies. Institutions like the Brookings Institution and the American Enterprise Institute are hubs where economists draft policy proposals that parties adopt. For instance, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, a cornerstone of Republican policy, was heavily influenced by economists like Kevin Hassett, who chaired the Council of Economic Advisers. Similarly, Democratic policies on healthcare and climate change often draw from economists at the Urban Institute or the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. These organizations act as bridges between academic research and political action, amplifying economists’ voices in the policy-making process.

However, the influence of economists is not without challenges. Partisan polarization often distorts their contributions, as parties cherry-pick data or theories to support preconceived agendas. For example, while most economists agree that trade benefits the economy overall, politicians may emphasize job losses in specific sectors to appeal to voters. This selective use of economic arguments undermines the credibility of economists and complicates their ability to shape policy objectively. To mitigate this, economists must communicate their findings clearly and engage with the public directly, bypassing partisan filters.

A practical takeaway for policymakers is to institutionalize mechanisms that ensure economists’ input is both heard and balanced. This could include bipartisan economic councils or mandatory cost-benefit analyses for major policies. For instance, the Congressional Budget Office, staffed by nonpartisan economists, provides critical assessments of legislation, helping lawmakers make informed decisions. By embedding economists in the policy process, governments can reduce ideological bias and prioritize evidence-based solutions.

Ultimately, the influence of economists on party platforms and government policies is a double-edged sword. While their expertise is indispensable for crafting effective policies, their impact depends on how their ideas are interpreted and applied. Economists must navigate this political landscape strategically, ensuring their research serves the public good rather than partisan interests. For citizens, understanding this dynamic is key to holding both economists and politicians accountable for the policies that shape their lives.

Understanding the Inner Workings of American Political Parties

You may want to see also

Ideological Leanings: Analyzing economists' alignment with conservative, liberal, or centrist political ideologies

Economists, often perceived as dispassionate analysts of markets and policies, are not immune to ideological leanings. Surveys and studies reveal a diverse spectrum of political affiliations among economists, though certain trends emerge. A 2013 survey by the *Initiative on Global Markets* found that a majority of economists leaned toward the Democratic Party in the U.S., often aligning with liberal or centrist ideologies. However, this does not imply uniformity; significant minorities identify with conservative or libertarian views. Globally, economists’ political leanings vary based on regional contexts, with European economists often favoring social democratic policies, while those in more market-oriented economies may lean conservative.

To analyze these alignments, consider the core principles of each ideology and how they intersect with economic theory. Conservative economists often emphasize free markets, limited government intervention, and fiscal responsibility, aligning with classical economic principles. Liberal economists, on the other hand, tend to support progressive taxation, social welfare programs, and government intervention to address market failures, reflecting Keynesian or institutionalist perspectives. Centrist economists may advocate for a balanced approach, combining market efficiency with targeted regulation and redistribution. For instance, a conservative economist might prioritize deregulation to spur growth, while a liberal economist might argue for higher taxes on the wealthy to fund education and healthcare.

A practical way to understand these leanings is to examine economists’ stances on specific policies. Take the minimum wage debate: conservative economists often oppose increases, citing potential job losses, while liberal economists argue that higher wages reduce poverty and stimulate demand. Centrist economists might propose a moderate increase paired with small business tax credits to mitigate negative effects. Similarly, on climate policy, liberal economists favor aggressive regulation and carbon pricing, conservatives prefer market-based solutions like cap-and-trade, and centrists might advocate for a mix of incentives and mandates.

One caution in analyzing these alignments is the risk of oversimplification. Economists’ views are shaped not only by ideology but also by empirical evidence, methodological preferences, and institutional contexts. For example, an economist may lean liberal but oppose certain welfare programs if data suggests inefficiency. Conversely, a conservative economist might support targeted government intervention in cases of market failure. Thus, ideological labels should be treated as broad frameworks rather than rigid categories.

In conclusion, while economists’ ideological leanings often align with conservative, liberal, or centrist political ideologies, these alignments are nuanced and context-dependent. Understanding these leanings requires examining how economic principles intersect with political values, as well as recognizing the role of evidence and pragmatism in shaping economists’ views. By doing so, one can better interpret economists’ policy recommendations and their implications for society.

Unveiling Antifa's Political Affiliations: Which Party Supports Their Movement?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Party Endorsements: Instances of economists publicly supporting or advising specific political parties

Economists, often perceived as neutral analysts of data and policy, occasionally step into the political arena by publicly endorsing or advising specific parties. These endorsements carry weight, as they lend credibility to a party’s economic platform and signal alignment with particular ideologies. For instance, Nobel laureate Paul Krugman has consistently supported the Democratic Party in the United States, advocating for progressive economic policies like stimulus spending and healthcare reform. His public stance reflects a broader trend of economists leaning toward parties that prioritize government intervention to address inequality and market failures.

In contrast, other economists align with conservative or libertarian parties that champion free-market principles and limited government. For example, Arthur Laffer, known for the "Laffer Curve," has advised the Republican Party and advocated for tax cuts as a means to stimulate economic growth. His work has been instrumental in shaping supply-side economics, a cornerstone of conservative economic policy. Such endorsements highlight how economists can become intellectual architects for specific party agendas, often influencing policy decisions with far-reaching consequences.

Internationally, economists’ party endorsements often reflect regional economic challenges and political contexts. In the United Kingdom, economist Thomas Piketty has publicly supported the Labour Party, emphasizing his research on wealth inequality and the need for progressive taxation. Conversely, economists like Niall Ferguson have aligned with the Conservative Party, arguing for fiscal discipline and market-driven solutions. These endorsements underscore how economists’ policy prescriptions are deeply tied to their diagnostic frameworks, which in turn align with specific political ideologies.

Endorsements are not without risk. Economists who publicly support parties may face criticism for perceived bias, potentially undermining their credibility as objective analysts. For instance, when economists like Jeffrey Sachs advise parties like the Democratic Party in the U.S. or the Social Democratic Party in Germany, their recommendations are often scrutinized for ideological leanings rather than empirical rigor. This tension between impartiality and advocacy is a recurring theme in the intersection of economics and politics.

Practical takeaways for understanding these endorsements include examining the economist’s body of work, the specific policies they advocate for, and the historical context of their support. For example, an economist endorsing a party advocating for universal basic income is likely rooted in research on poverty alleviation and labor market dynamics. By dissecting these endorsements, observers can better grasp the ideological and empirical underpinnings of political economic platforms. Ultimately, while economists’ party endorsements are not universal, they provide valuable insights into the alignment of economic theory with political practice.

Are Political Parties Government Entities? Understanding Their Role and Function

You may want to see also

Non-Partisan Roles: Economists' efforts to remain politically neutral in academic and advisory roles

Economists often find themselves at the intersection of policy and politics, yet many strive to maintain a non-partisan stance in their academic and advisory roles. This commitment to neutrality is rooted in the belief that economic analysis should be grounded in evidence and rigorous methodology, not ideological bias. For instance, when advising governments or publishing research, economists frequently emphasize the importance of data-driven conclusions over party-aligned narratives. This approach ensures their work remains credible and applicable across the political spectrum.

One practical strategy economists employ to uphold non-partisanship is the use of counterfactual analysis. By examining how different policies might have played out under alternate scenarios, they can isolate the effects of specific interventions without favoring one political ideology over another. For example, an economist might compare the economic outcomes of a tax cut versus increased government spending, presenting both the benefits and drawbacks of each approach. This method allows policymakers to make informed decisions based on objective evidence rather than partisan rhetoric.

In academic settings, economists often adhere to peer review processes that prioritize methodological rigor over political alignment. Journals and conferences typically require authors to disclose potential conflicts of interest and justify their analytical choices, fostering transparency and accountability. Additionally, interdisciplinary collaboration—working with sociologists, political scientists, and other experts—helps economists avoid the echo chambers that can arise within single-discipline research. Such practices reinforce the non-partisan nature of their work, ensuring it serves the broader public interest.

However, maintaining neutrality is not without challenges. Economists may face pressure from funding sources, media outlets, or even colleagues to align their findings with specific political agendas. To mitigate this, professional organizations like the American Economic Association (AEA) have established ethical guidelines that emphasize impartiality and integrity. Economists are encouraged to disclose funding sources, avoid advocacy in their professional capacity, and clearly distinguish between empirical findings and personal opinions. These safeguards help preserve the trustworthiness of their work in an increasingly polarized political landscape.

Ultimately, the non-partisan role of economists is essential for fostering informed public debate and effective policymaking. By prioritizing evidence over ideology, they provide a critical foundation for addressing complex societal challenges. For individuals seeking to engage with economic research or advice, a key takeaway is to look for transparency in methodology and funding disclosures. This ensures the information is reliable and free from political bias, enabling better decision-making at both individual and collective levels.

Kim Cheatle's Political Affiliation: Uncovering Her Party Allegiance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Economists do not uniformly affiliate with a single political party. Their views are diverse and often based on economic principles rather than partisan politics. While some may lean toward Democratic or Republican parties in the U.S., many remain independent or focus on policy analysis rather than party loyalty.

Economists’ policy preferences vary widely. Some support liberal policies like progressive taxation and social welfare programs, while others advocate for conservative approaches like free markets and limited government intervention. Their stances are typically grounded in economic theory and empirical evidence rather than ideological alignment.

Globally, economists do not align with a single political party. Their affiliations depend on regional political landscapes and their individual beliefs. In some countries, they may support center-left, center-right, or independent parties, but their primary focus is often on economic analysis and policy effectiveness.