The question of what political party mass killers are registered with is a complex and sensitive issue that often sparks intense debate. While there is no definitive evidence linking mass killings to a specific political party, media coverage and public discourse frequently highlight the affiliations of perpetrators, leading to assumptions and generalizations. It is crucial to approach this topic with nuance, recognizing that individuals who commit such heinous acts do not represent the entirety of any political group. Instead, their actions are typically driven by a combination of personal, psychological, and societal factors that transcend partisan boundaries. Examining this question requires a balanced perspective, avoiding the pitfalls of politicization while acknowledging the broader societal and ideological contexts that may influence extreme behavior.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Party Affiliation Trends: Analyzing common political party registrations among mass killers in historical data

- Republican vs. Democrat: Comparing mass killer registrations between the two major U.S. parties

- Third-Party Registrations: Investigating if mass killers are affiliated with minor or fringe political parties

- International Party Links: Exploring political party ties of mass killers outside the United States

- No Party Affiliation: Examining cases where mass killers are unregistered or politically unaffiliated

Party Affiliation Trends: Analyzing common political party registrations among mass killers in historical data

Mass killers, by their very nature, defy simple categorization, yet patterns in their political affiliations have emerged from historical data. A comprehensive analysis of these trends reveals a complex interplay between ideology, personal grievance, and societal factors. While no single political party can be solely blamed for mass killings, certain affiliations appear more frequently than others, prompting a closer examination of the underlying dynamics.

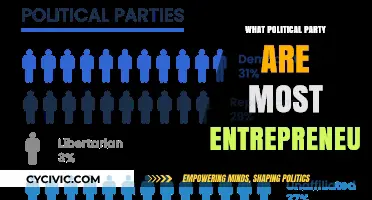

Research indicates a disproportionate representation of right-wing ideologies among mass killers, particularly those motivated by racial hatred or anti-government sentiments. Studies analyzing the political leanings of perpetrators in the United States, for instance, have found a higher incidence of registered Republicans or individuals espousing conservative views among mass shooters compared to the general population. This correlation, however, does not imply causation. It's crucial to avoid simplistic conclusions and acknowledge the multifaceted nature of these tragedies.

It's important to note that not all mass killers are politically motivated. Many acts of violence stem from personal grievances, mental health issues, or a combination of factors. However, when political ideology does play a role, understanding the specific beliefs and grievances that drive individuals to commit such atrocities is essential for developing effective prevention strategies.

Analyzing party affiliation trends can serve as a starting point for identifying potential risk factors and informing targeted interventions. For example, recognizing the prevalence of right-wing extremism in certain cases could lead to increased monitoring of online hate speech forums and the development of programs aimed at countering radicalization.

Ultimately, the goal is not to stigmatize entire political groups but to identify and address the specific ideologies and narratives that contribute to violence. By carefully examining the political affiliations of mass killers within the broader context of their motivations and societal influences, we can gain valuable insights into preventing future tragedies. This requires a nuanced approach that avoids generalizations and focuses on understanding the complex interplay of factors that lead individuals down the path of violence.

Mechanical Solidarity: Uniting Political Parties Through Shared Interests and Goals

You may want to see also

Republican vs. Democrat: Comparing mass killer registrations between the two major U.S. parties

Mass killers, by their very nature, defy simple categorization, and attempting to link their actions to political party affiliation is fraught with complexity. However, a closer examination of available data and case studies reveals intriguing patterns when comparing Republican and Democratic registrations among perpetrators of mass shootings in the U.S. While definitive conclusions remain elusive, certain trends emerge that challenge common assumptions and highlight the need for nuanced understanding.

A 2019 study by the Violence Project, which analyzed 167 mass shooters in the U.S. between 1966 and 2019, found that 54% of perpetrators with known political affiliations identified as Republican or conservative, compared to 21% who identified as Democratic or liberal. This disparity, while notable, must be interpreted cautiously. The study acknowledges limitations, including the small sample size of politically affiliated shooters and the potential for bias in self-reported data.

It's crucial to avoid simplistic causation arguments. Political affiliation alone cannot explain the complex motivations behind mass shootings, which often involve a toxic mix of mental health issues, personal grievances, access to firearms, and societal factors. However, the data suggests a correlation worthy of further exploration.

One hypothesis is that the Republican Party's emphasis on individualism, gun rights, and, in some cases, rhetoric that demonizes certain groups, might resonate with individuals predisposed to violence. Conversely, the Democratic Party's focus on social welfare, gun control, and inclusivity might be less appealing to potential perpetrators.

This doesn't imply that all Republicans are potential mass shooters or that Democrats are immune. It simply highlights a statistical trend that demands further investigation. Understanding these patterns can inform prevention strategies, not by targeting specific political groups, but by addressing underlying societal issues that contribute to violence, regardless of political affiliation.

Winning Political Approval for Your Urban Empire: Strategies for Success

You may want to see also

Third-Party Registrations: Investigating if mass killers are affiliated with minor or fringe political parties

Mass killers often evade clear political affiliations, but a closer examination of third-party registrations reveals intriguing patterns. While major parties dominate political discourse, minor or fringe parties occasionally surface in the backgrounds of these perpetrators. For instance, the 2011 Norway attacks by Anders Behring Breivik were rooted in his ties to far-right, anti-immigrant ideologies, though he was not formally registered with any specific fringe party. Such cases prompt a deeper investigation into whether third-party affiliations serve as incubators for extremist ideologies that escalate into violence.

Analyzing voter registration data for mass killers presents methodological challenges. Many fringe parties lack centralized databases, and perpetrators may not formally register but still align ideologically. A 2020 study by the Violence Project found that 54% of mass shooters in the U.S. expressed extremist beliefs, yet only a fraction were tied to formal political groups. This suggests that third-party registrations may be less predictive of violence than the broader ideological ecosystems these parties represent. Researchers must therefore broaden their focus to include online forums, social media, and unofficial group memberships where radicalization often occurs.

To investigate this phenomenon effectively, follow these steps: First, cross-reference voter registration records with known mass killers, focusing on states with accessible public databases. Second, identify fringe parties by their platform extremes—anti-government, white supremacist, or anarchistic ideologies. Third, correlate these findings with behavioral indicators, such as manifesto writings or social media activity. Caution: Avoid conflating ideological sympathy with direct party affiliation, as many perpetrators act independently. Finally, collaborate with political scientists and criminologists to contextualize findings within broader trends of political extremism.

Persuasively, the focus on third-party registrations should not overshadow the role of mainstream political rhetoric in normalizing extremist views. Fringe parties often amplify ideas that originate in more centrist discourse. For example, anti-immigrant sentiments, when legitimized by major figures, can radicalize individuals who then gravitate toward minor parties. Policymakers must address this pipeline by holding all political actors accountable for the consequences of their rhetoric. Practical tip: Monitor local and national political speeches for dehumanizing language, which often precedes spikes in hate crimes.

Comparatively, international data offers a broader perspective. In Europe, fringe parties like Germany’s AfD or Greece’s Golden Dawn have been linked to extremist violence, though direct ties to mass killers remain rare. In contrast, the U.S. lacks a robust multi-party system, pushing extremists into loosely organized militias or online networks. This divergence highlights the importance of cultural and political contexts in shaping radicalization pathways. Takeaway: While third-party registrations provide a starting point, understanding mass killers requires a holistic approach that considers ideology, community, and global influences.

Understanding the Motivations Behind Joining Political Parties: A Deep Dive

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$8.99 $10.99

International Party Links: Exploring political party ties of mass killers outside the United States

Mass killers outside the United States often exhibit political affiliations that reflect local ideologies, historical grievances, or global extremist networks. For instance, Anders Behring Breivik, the perpetrator of the 2011 Norway attacks, was linked to far-right, anti-Islamic ideologies but was not formally registered with any political party. Conversely, Brenton Tarrant, the Christchurch mosque shooter, openly aligned with white supremacist and eco-fascist movements, though these are more subcultures than formal parties. Such cases highlight how political ties abroad are often informal yet deeply rooted in extremist ideologies.

Analyzing these ties requires distinguishing between formal party membership and ideological alignment. In Europe, far-right parties like the National Rally in France or the Alternative for Germany (AfD) have not directly produced mass killers, but their rhetoric often resonates with perpetrators. Similarly, in Asia, some mass killings have been tied to nationalist or separatist movements, such as the 2019 El Paso shooting, where the shooter’s manifesto echoed anti-immigrant sentiments. However, formal party registration is rare, as extremists often operate in fringe groups or online communities rather than mainstream political structures.

A comparative approach reveals regional variations. In the Middle East, mass killings are frequently linked to religious extremism, with perpetrators aligning with groups like ISIS or Al-Qaeda rather than political parties. In contrast, Latin America has seen mass violence tied to drug cartels or paramilitary groups, which may have political agendas but lack formal party structures. These differences underscore the importance of context: political ties abroad are often indirect, tied to movements or ideologies rather than registered party affiliations.

To explore these links effectively, researchers should focus on three steps: (1) Identify the ideological motivations of perpetrators through manifestos, social media, or trial records; (2) Trace connections to extremist groups or movements, even if they lack formal party status; and (3) Analyze how local political climates or historical conflicts may fuel radicalization. Caution is necessary, however, as conflating extremist ideologies with legitimate political parties can stigmatize entire movements. The goal is to understand the nuanced relationship between politics and violence, not to oversimplify complex phenomena.

Ultimately, the international landscape of mass killers’ political ties reveals a pattern of informal, ideological alignment rather than formal party registration. While far-right, nationalist, and religious extremist movements frequently provide the framework for radicalization, perpetrators rarely belong to established political parties. This distinction is critical for policymakers and researchers seeking to address the root causes of mass violence without mischaracterizing political landscapes. By focusing on ideologies and movements, rather than party labels, we can better understand—and potentially mitigate—the global threat of politically motivated mass killings.

Patrick Dempsey's Political Party: Unveiling the Actor's Political Affiliation

You may want to see also

No Party Affiliation: Examining cases where mass killers are unregistered or politically unaffiliated

A significant number of mass killers have no known political party affiliation, complicating efforts to draw direct links between partisan ideology and extreme violence. Unlike cases where perpetrators explicitly align with far-right, far-left, or other political movements, unaffiliated individuals often leave behind motives that are deeply personal, psychologically complex, or entirely opaque. For instance, the 2017 Las Vegas shooter, Stephen Paddock, exhibited no clear political leanings, with investigators concluding his actions lacked a coherent ideological motive. Such cases underscore the danger of oversimplifying mass violence as a partisan issue.

Analyzing these unaffiliated cases reveals a pattern of isolation, mental health struggles, and grievances rooted in personal rather than political realms. Take the 2012 Sandy Hook shooter, Adam Lanza, whose obsession with mass shootings and social withdrawal predominated over any political expression. Similarly, the 2019 El Paso shooter, despite targeting Hispanics, was not registered with any party, and his manifesto blended white supremacist rhetoric with incoherent personal rants. These examples highlight how political unaffiliation often coincides with a lack of structured ideology, making prevention efforts more challenging.

To address this phenomenon, focus should shift from partisan blame games to systemic interventions. Mental health screening, threat assessment programs, and community-based support networks can identify at-risk individuals before they escalate to violence. For instance, the Behavioral Intervention Team model, implemented in schools and workplaces, has successfully flagged concerning behaviors unrelated to political beliefs. Additionally, public awareness campaigns can destigmatize seeking help for mental health issues, reducing the isolation often seen in unaffiliated perpetrators.

Comparatively, unaffiliated mass killers differ from their politically motivated counterparts in their lack of a broader movement or ideology to target. While extremist groups can be monitored and disrupted, lone actors with no organizational ties require a more nuanced approach. Law enforcement agencies increasingly rely on data analytics to detect patterns in online behavior, such as frequenting violent forums or stockpiling weapons, regardless of political expression. This strategy, coupled with community engagement, offers a more effective path than partisan finger-pointing.

In conclusion, the absence of political affiliation among mass killers should not obscure the urgency of addressing the underlying factors driving their actions. By focusing on mental health, social isolation, and behavioral indicators, society can develop proactive measures that transcend political divides. The challenge lies not in assigning blame but in fostering a collective responsibility to prevent violence before it occurs.

Joining the Ranks: A Step-by-Step Guide to Political Party Membership

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

There is no definitive data linking mass killers to a specific political party, as motivations vary widely and are often unrelated to political affiliation.

Mass killers do not consistently align with either conservative or liberal parties; their actions are typically driven by personal, psychological, or ideological factors rather than party politics.

Studies show no clear pattern of mass killers being disproportionately registered with any specific political party in the U.S., as their backgrounds and beliefs are highly diverse.