Exploring the question of which political parties U.S. presidents would align with if they were alive today offers a fascinating lens into the evolution of American politics. Many early presidents, such as George Washington, eschewed party affiliation, while others like Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton laid the groundwork for the Democratic-Republican and Federalist Parties, respectively. If figures like Abraham Lincoln were active in contemporary politics, his emphasis on unity and progressive policies might place him in a more moderate or reform-oriented faction, rather than strictly adhering to today’s polarized Republican or Democratic Parties. Similarly, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies might align him with the modern Democratic Party, while Ronald Reagan’s conservative principles would likely resonate with today’s Republican Party. This thought experiment highlights how historical leaders’ ideologies might adapt to the current political landscape, revealing both continuity and change in American political thought.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Founding Fathers' Party Affiliations: Hypothetical party placements for Washington, Jefferson, Adams, and Hamilton

- Modern Presidents' Ideologies: Aligning recent presidents (Obama, Trump, Biden) with current party platforms

- Historical Party Shifts: How presidents like Lincoln or FDR would fit today’s party dynamics

- Third Party Presidents: Imagining presidents like Teddy Roosevelt or Bernie Sanders in alternative parties

- Global Party Comparisons: Matching U.S. presidents with international parties (e.g., UK Conservatives, Labour)

Founding Fathers' Party Affiliations: Hypothetical party placements for Washington, Jefferson, Adams, and Hamilton

The Founding Fathers, though operating in an era before the modern two-party system, exhibited ideologies and principles that align with today’s political parties. Hypothetically placing George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Alexander Hamilton into contemporary party affiliations requires dissecting their core beliefs and actions. Washington, for instance, famously warned against the dangers of partisanship in his Farewell Address, advocating for unity and a strong federal government. This pragmatism and emphasis on national cohesion suggest he might lean toward the moderate wing of either major party, though his disdain for factionalism could make him an independent.

Jefferson, a champion of states’ rights, agrarianism, and limited federal power, aligns closely with the modern libertarian wing of the Republican Party or even the Libertarian Party. His Democratic-Republican Party, which he co-founded, emphasized individual liberty and opposition to centralized authority—values echoed in today’s conservative libertarianism. However, his progressive views on education and his role in the Louisiana Purchase complicate a strict ideological fit, highlighting the difficulty of mapping historical figures onto modern parties.

Adams, a Federalist who supported a strong central government, national institutions, and a robust executive branch, would likely find a home in the moderate to conservative wing of the Republican Party. His belief in the rule of law, religious morality in governance, and skepticism of radical democracy resonate with modern conservative principles. Yet, his elitist tendencies and support for a strong presidency might alienate him from populist factions within the GOP.

Hamilton, the architect of America’s financial system, advocated for a powerful federal government, industrialization, and a national bank—positions that align him with the moderate to conservative wing of the Democratic Party or even the centrist wing of the Republican Party. His belief in a strong executive and his role in establishing a capitalist economy make him a natural fit for pro-business, fiscally conservative ideologies. However, his elitism and distrust of direct democracy might distance him from progressive Democrats.

In practice, these hypothetical placements reveal the limitations of retrofitting historical figures into modern parties. The Founding Fathers’ ideologies were shaped by the Revolutionary era, not the 21st century. For instance, Jefferson’s agrarian focus and Hamilton’s financial policies reflect debates of their time, not today’s polarized issues like healthcare or climate change. To apply this analysis effectively, consider studying primary sources like the Federalist Papers or Jefferson’s writings to understand their principles directly. This approach avoids oversimplification and provides a richer context for their hypothetical party affiliations.

How Political Parties Shape Congress: Strategies and Impact Explained

You may want to see also

Modern Presidents' Ideologies: Aligning recent presidents (Obama, Trump, Biden) with current party platforms

Recent U.S. presidents—Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden—have embodied distinct ideologies that align closely with the evolving platforms of their respective parties. Obama’s presidency, rooted in progressive ideals, emphasized healthcare reform, climate action, and social justice, mirroring the modern Democratic Party’s focus on equity and government intervention. Trump’s tenure, marked by populist nationalism, tax cuts, and deregulation, reflected the Republican Party’s shift toward conservative populism and economic libertarianism. Biden, while centrist in approach, has championed Democratic priorities like infrastructure investment, environmental policy, and social safety nets, though with a more pragmatic tone. These alignments reveal how recent presidents have both shaped and been shaped by their party’s contemporary identity.

Consider Obama’s signature achievement, the Affordable Care Act, which expanded healthcare access and set a precedent for Democratic policy on social welfare. His administration’s emphasis on multilateral diplomacy and environmental initiatives like the Paris Agreement also aligned with the party’s globalist and progressive stances. In contrast, Trump’s "America First" agenda, characterized by trade wars, immigration restrictions, and skepticism of international alliances, redefined the Republican Party’s platform to prioritize nationalism and unilateralism. His tax cuts and deregulation efforts further solidified the GOP’s pro-business, small-government ethos. These examples illustrate how each president’s actions have become touchstones for their party’s ideology.

Biden’s presidency offers a unique case study in balancing progressive demands with moderate pragmatism. His American Rescue Plan and Inflation Reduction Act reflect Democratic priorities but are executed with an eye toward bipartisan appeal and fiscal responsibility. This approach highlights the modern Democratic Party’s internal tension between its progressive and centrist wings. Meanwhile, Biden’s foreign policy, marked by reengagement with allies and a focus on democracy promotion, contrasts sharply with Trump’s isolationist tendencies, underscoring the ideological divide between the parties on global leadership.

To understand these alignments, examine the presidents’ legislative priorities and rhetorical strategies. Obama’s emphasis on "hope and change" framed progressive policies as transformative, while Trump’s "Make America Great Again" slogan encapsulated his populist, nostalgic appeal. Biden’s "Build Back Better" agenda, though less catchy, reflects a focus on recovery and unity. These slogans are not just campaign tools but distillations of their party’s core messages. For practical analysis, compare their State of the Union addresses or major policy speeches to identify recurring themes and their alignment with current party platforms.

In conclusion, aligning recent presidents with current party platforms reveals how individual leadership both reflects and reshapes party ideologies. Obama’s progressivism, Trump’s populism, and Biden’s centrism have each left indelible marks on the Democratic and Republican Parties. By studying their policies, rhetoric, and priorities, we gain insight into the evolving nature of American political parties and the role of presidential leadership in defining their trajectories. This analysis is not just historical but a guide to understanding the ideological battles shaping today’s political landscape.

Understanding 'Bolt the Party': Political Disaffiliation and Its Implications

You may want to see also

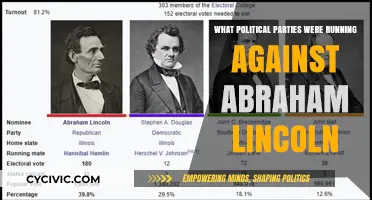

Historical Party Shifts: How presidents like Lincoln or FDR would fit today’s party dynamics

The Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln’s era was defined by its commitment to abolition, national unity, and a strong federal government—principles that would align more closely with today’s Democratic Party. Lincoln’s emphasis on economic modernization, infrastructure investment, and social justice (e.g., the Emancipation Proclamation) mirrors modern Democratic priorities. Conversely, his opposition to states’ rights and his belief in federal authority to address national crises would clash with the current Republican Party’s emphasis on state sovereignty and limited government. Lincoln’s pragmatic approach to governance, however, might make him a moderate in today’s polarized landscape, struggling to fit neatly into either party.

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal policies—expanding social safety nets, regulating Wall Street, and using federal power to combat economic inequality—would place him squarely within the modern Democratic Party. His belief in an active government role during the Great Depression aligns with today’s progressive wing, advocating for healthcare expansion, climate action, and wealth redistribution. Yet, FDR’s ability to appeal to both urban and rural voters, as well as his foreign policy hawkishness, might make him a bridge between moderate and progressive Democrats. His stance on issues like immigration or racial justice, however, would likely be scrutinized by today’s standards, revealing the complexities of historical figures in contemporary contexts.

Consider the paradox of Ronald Reagan, whose policies would now place him on the moderate-to-liberal wing of the Republican Party. His support for tax cuts and deregulation aligns with today’s GOP, but his compromises on taxes, immigration reform (e.g., the 1986 amnesty), and environmental protection (e.g., the Montreal Protocol) would be anathema to the party’s current base. This illustrates how historical figures often defy modern party labels, as their ideologies were shaped by different political and social pressures.

To understand these shifts, examine the evolution of party platforms. The Democratic Party’s transformation from a pro-segregation, states’ rights coalition to a multicultural, federalist movement contrasts sharply with the Republican Party’s shift from Lincoln’s nationalistic vision to today’s focus on individualism and state autonomy. Practical tip: When analyzing historical figures in modern contexts, focus on core principles (e.g., Lincoln’s belief in equality, FDR’s activism) rather than specific policies, as issues like slavery or the Gold Standard no longer dominate debates.

A cautionary note: Retroactively assigning modern party labels to historical presidents risks oversimplifying their legacies. For instance, while Lincoln’s anti-slavery stance aligns with today’s Democrats, his views on race were still shaped by 19th-century norms. Similarly, FDR’s internment of Japanese Americans would be condemned by both parties today. The takeaway? Historical figures are products of their time, and their ideologies cannot be neatly transplanted into contemporary politics. Instead, study their principles and adaptability to understand how they might navigate today’s challenges.

Farmers Alliance's Legacy: Birth of the Populist Political Party

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$12.99 $12.99

$8.95

Third Party Presidents: Imagining presidents like Teddy Roosevelt or Bernie Sanders in alternative parties

The United States has long been dominated by a two-party system, with the Democratic and Republican parties holding a near-monopoly on presidential power. Yet, history and modern politics offer intriguing "what if" scenarios where figures like Teddy Roosevelt or Bernie Sanders could have reshaped the presidency from the platform of a third party. Imagine Roosevelt, a progressive maverick, running under the banner of the Progressive Party—not as a one-time experiment in 1912, but as a sustained force. His trust-busting, conservationist, and worker-friendly policies might have redefined American politics, creating a third-party legacy rather than a footnote. Similarly, Bernie Sanders, a democratic socialist, could have led a revitalized Green or Socialist Party, pushing issues like universal healthcare and wealth inequality to the forefront, unencumbered by the compromises of the Democratic Party.

Analyzing these scenarios reveals the structural barriers third-party candidates face. The Electoral College, winner-take-all systems, and ballot access laws are designed to favor the two major parties. Yet, a third-party president could disrupt this dynamic by leveraging grassroots movements and technological advancements. For instance, Sanders’ 2016 and 2020 campaigns demonstrated the power of small-dollar donations and social media to challenge establishment candidates. If he had run as a Green Party candidate, his ability to mobilize young voters and independents might have forced a realignment of the political landscape, much like Roosevelt’s Bull Moose campaign did in 1912.

Instructively, for third-party candidates to succeed, they must focus on three key strategies: coalition-building, policy differentiation, and media savvy. Teddy Roosevelt’s Progressive Party attracted labor unions, farmers, and middle-class reformers by offering a clear alternative to both corporate Republicans and tepid Democrats. Sanders, as a third-party candidate, could similarly unite environmentalists, labor activists, and social justice advocates under a banner of systemic change. However, both would need to navigate the media landscape effectively, using platforms like podcasts, YouTube, and TikTok to bypass traditional gatekeepers and reach voters directly.

Comparatively, the success of third-party presidents in other democracies offers lessons for the U.S. In countries like Germany and New Zealand, proportional representation and coalition governments allow smaller parties to wield influence. While the U.S. system is different, a third-party president could still enact change by leveraging executive orders, public pressure, and strategic alliances in Congress. For example, Roosevelt’s use of the bully pulpit to champion progressive causes shows how a determined president can shape public opinion and force legislative action, even without a majority party behind them.

Descriptively, imagine a 2024 election where Bernie Sanders runs as the Green Party candidate, facing off against a Republican and a centrist Democrat. His campaign rallies are packed with enthusiastic supporters, his policy proposals dominate social media, and his debates highlight the stark differences between his vision and the status quo. While he might not win the Electoral College outright, his strong showing could force a contingent election in the House, where his ideas gain traction and push the eventual winner to adopt parts of his agenda. This scenario, while speculative, illustrates how a third-party president could transform American politics, even without winning the presidency.

Practically, for voters and activists, supporting third-party candidates requires a long-term perspective. Focus on local and state races to build a foundation for national success. Advocate for electoral reforms like ranked-choice voting and public campaign financing to level the playing field. And most importantly, embrace the idea that change often begins outside the mainstream. Whether it’s Teddy Roosevelt’s progressive vision or Bernie Sanders’ socialist ideals, third-party presidents represent not just an alternative to the two-party system, but a reimagining of what American politics could be.

Why Third Parties Struggle: Barriers in Our Political System

You may want to see also

Global Party Comparisons: Matching U.S. presidents with international parties (e.g., UK Conservatives, Labour)

If we were to match U.S. presidents with international political parties, the exercise would reveal fascinating alignments and contrasts in ideology, policy priorities, and governing style. For instance, Ronald Reagan, known for his conservative economic policies and strong national defense stance, would likely find a natural fit with the UK Conservative Party. Both Reagan and the Conservatives championed free-market capitalism, deregulation, and a robust foreign policy, making this comparison a straightforward yet insightful pairing. Similarly, Margaret Thatcher’s leadership in the 1980s mirrored Reagan’s approach, reinforcing the transatlantic conservative alliance of that era.

Contrastingly, a president like Franklin D. Roosevelt, architect of the New Deal and a proponent of expansive government intervention during the Great Depression, would align more closely with the UK Labour Party. Labour’s emphasis on social welfare, public services, and economic redistribution echoes Roosevelt’s progressive policies. Similarly, Barack Obama’s focus on healthcare reform and social justice initiatives could be likened to the centre-left policies of the Canadian Liberal Party, which balances fiscal responsibility with social progressivism. These comparisons highlight how U.S. presidents often embody ideologies that resonate with specific international parties.

However, not all matches are clear-cut. Donald Trump’s populist, nationalist, and protectionist agenda defies easy categorization within traditional European party structures. While his economic nationalism might align with some aspects of the UK’s Brexit-era Conservatives, his skepticism of multilateral institutions and emphasis on "America First" could also find echoes in parties like France’s National Rally. This complexity underscores the challenge of mapping U.S. presidencies onto international parties, as American politics often blends elements that don’t neatly fit into foreign frameworks.

To make these comparisons more actionable, consider a step-by-step approach: first, identify the core policies and values of a U.S. president (e.g., Joe Biden’s focus on climate change and social equity). Next, research international parties with similar priorities (e.g., Germany’s Green Party or the Swedish Social Democratic Party). Finally, analyze the nuances—such as cultural context or historical differences—that might complicate the match. This method not only deepens understanding of global political landscapes but also highlights the unique characteristics of American leadership.

In conclusion, matching U.S. presidents with international parties offers a lens to explore shared ideologies and divergent approaches across borders. While some pairings are intuitive, others reveal the complexities of political identities. This exercise isn’t just academic—it’s a practical tool for policymakers, students, and citizens to grasp the global implications of U.S. leadership and the interconnectedness of modern politics. By examining these comparisons, we gain a richer appreciation of how American presidencies fit into—and sometimes challenge—the broader tapestry of international political movements.

Unveiling the Political Party Behind Roe v. Wade Legislation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

George Washington would likely remain unaffiliated or advocate for a centrist, non-partisan approach, as he famously warned against the dangers of political factions in his Farewell Address.

Abraham Lincoln would likely align with the modern Republican Party, as he was the first president to be elected under the Republican banner and championed principles like preserving the Union and ending slavery.

Franklin D. Roosevelt would likely remain a Democrat, as his New Deal policies and progressive agenda align closely with the modern Democratic Party's focus on social welfare and government intervention.

Ronald Reagan would still identify as a Republican, as his conservative policies on taxation, deregulation, and strong national defense remain core principles of the modern Republican Party.

Theodore Roosevelt might align with the modern Democratic Party due to his progressive reforms, focus on environmental conservation, and support for a more active federal government, though he could also appeal to moderate Republicans.