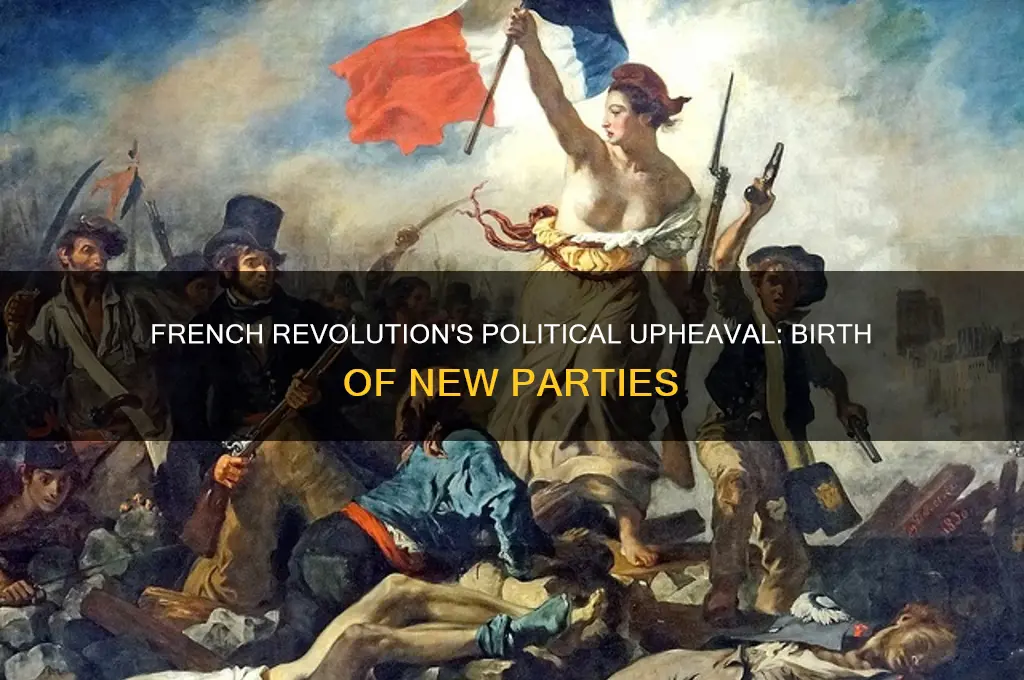

The French Revolution, a period of profound social and political upheaval, gave rise to several political factions that shaped the course of French history. Among these, the most prominent were the Jacobins, Girondins, and Cordeliers, each advocating distinct ideologies and visions for France's future. The Jacobins, led by figures like Maximilien Robespierre, championed radical republicanism and egalitarian principles, while the Girondins, initially more moderate, supported a constitutional monarchy before aligning with republican ideals. The Cordeliers, a more populist group, focused on the rights of the common people and often allied with the Jacobins. These factions, along with others like the Feuillants and the Plain, emerged as the Revolution progressed, reflecting the deep divisions and evolving political landscape of the time. Their creation and rivalry were pivotal in determining the Revolution's trajectory, from the fall of the monarchy to the rise of the First French Republic.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of Parties | Multiple factions emerged, not formal parties as we know today. |

| Major Factions | Girondins, Montagnards (Jacobins), The Plain, Feuillants, Cordeliers. |

| Ideological Spectrum | Ranged from liberal constitutional monarchy to radical republicanism. |

| Girondins | Moderate republicans, favored a decentralized government, pro-war. |

| Montagnards (Jacobins) | Radical republicans, centralized power, led by Robespierre, pro-war. |

| The Plain | Centrist group, often swung between Girondins and Montagnards. |

| Feuillants | Constitutional monarchists, supported limited monarchy, opposed revolution. |

| Cordeliers | Radical left-wing group, advocated for direct democracy and social reform. |

| Duration | Most factions were active during the Revolution (1789–1799). |

| Key Figures | Girondins: Jacques Pierre Brissot; Montagnards: Maximilien Robespierre. |

| Political Influence | Shaped the course of the Revolution, leading to the Reign of Terror. |

| Legacy | Laid the groundwork for modern political ideologies and party systems. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Girondins: Moderate republicans, initially dominant, advocated for constitutional monarchy and decentralized power

- Montagnards: Radical republicans, led by Robespierre, pushed for democracy and social reforms

- Jacobins: Influential club supporting revolutionary ideals, played key role in Reign of Terror

- Cordeliers: Left-wing group, focused on popular sovereignty and rights of the poor

- Feuillants: Conservative faction, supported constitutional monarchy, opposed radical revolutionary measures

Girondins: Moderate republicans, initially dominant, advocated for constitutional monarchy and decentralized power

The Girondins, a pivotal faction during the French Revolution, emerged as the early standard-bearers of moderate republicanism. Initially dominant in the National Assembly, they championed a vision of France that balanced revolutionary ideals with pragmatic governance. Their core tenets included support for a constitutional monarchy, a system they believed would temper royal power while preserving social stability. Equally significant was their advocacy for decentralized power, reflecting their roots in provincial France and their distrust of centralized authority. This dual focus set them apart from more radical factions, positioning them as architects of a middle ground in a tumultuous era.

To understand the Girondins’ appeal, consider their strategic approach to political reform. Unlike the Jacobins, who sought to dismantle the monarchy entirely, the Girondins proposed a limited monarchy, where the king would reign but not rule. This compromise aimed to appease both revolutionary fervor and conservative resistance. Their emphasis on decentralization, meanwhile, was not merely ideological but practical. By shifting power to local assemblies, they hoped to foster civic engagement and mitigate the risks of tyranny. For modern readers, this strategy offers a lesson in balancing idealism with realism, a principle applicable to contemporary debates on federalism and local governance.

A closer examination of the Girondins’ downfall reveals the fragility of their moderate stance. Their initial dominance was undermined by their inability to navigate the escalating radicalism of the Revolution. Their opposition to the execution of Louis XVI, for instance, alienated them from more extreme factions, while their provincial focus left them vulnerable to accusations of disloyalty to Paris. This cautionary tale underscores the challenges of maintaining moderation in polarized times. For those seeking to implement centrist policies today, the Girondins’ experience serves as a reminder of the importance of adaptability and coalition-building in the face of ideological extremes.

Practically speaking, the Girondins’ legacy offers actionable insights for political strategists. Their focus on constitutional monarchy and decentralization provides a blueprint for crafting inclusive governance models. To emulate their approach, consider the following steps: first, identify areas where centralized power can be devolved to local bodies, fostering community ownership. Second, advocate for constitutional safeguards that limit executive authority while ensuring accountability. Finally, prioritize dialogue across ideological divides to prevent the erosion of moderate positions. By adopting these strategies, modern political movements can avoid the pitfalls that befell the Girondins while advancing their vision of balanced governance.

In conclusion, the Girondins’ advocacy for constitutional monarchy and decentralized power represents a nuanced response to the challenges of revolutionary France. Their rise and fall illustrate both the potential and peril of moderate republicanism. For today’s policymakers and activists, their story is a call to embrace pragmatic idealism, to decentralize power where possible, and to remain vigilant against the polarizing forces that can undermine centrist visions. By studying the Girondins, we gain not just historical insight but a practical guide to navigating the complexities of political reform.

Will Vijay Enter Politics? Analyzing the Superstar's Political Future

You may want to see also

Montagnards: Radical republicans, led by Robespierre, pushed for democracy and social reforms

The Montagnards, perched on the highest benches of the National Convention, earned their name from their physical position but embodied a far more significant elevation in revolutionary ideals. Led by Maximilien Robespierre, they were the radical republicans of their time, advocating for a democracy that extended beyond the bourgeoisie to encompass the common people. Their agenda was not merely political but deeply social, aiming to dismantle the remnants of feudalism and establish a society where liberty, equality, and fraternity were not just slogans but lived realities.

To understand the Montagnards’ impact, consider their key policies. They championed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, but unlike their more moderate counterparts, they insisted on its universal application. This meant not just political rights for the elite but also economic measures like price controls on essential goods and the redistribution of land. Robespierre’s Committee of Public Safety, though often criticized for its authoritarian methods, was the engine driving these reforms, ensuring that the Revolution’s benefits reached the sans-culottes—the working-class backbone of their support.

A comparative analysis reveals the Montagnards’ uniqueness. While the Girondins, their rivals, favored a more limited democracy and hesitated to challenge the economic status quo, the Montagnards were unapologetically radical. They saw the Revolution as an opportunity to upend centuries of inequality, not just to replace one ruling class with another. Their insistence on social reforms, such as public education and welfare, set them apart as visionaries in an era dominated by political maneuvering.

However, their radicalism came at a cost. The Reign of Terror, a period of intense political repression, is often cited as evidence of their extremism. Yet, it’s crucial to contextualize this phase. Facing internal and external threats, the Montagnards believed drastic measures were necessary to safeguard the Revolution. While their methods were controversial, their commitment to their ideals remained unwavering. Robespierre’s famous declaration, “The Revolution is the war of liberty against its enemies,” encapsulates their mindset—a relentless pursuit of justice, even in the face of opposition.

For modern readers, the Montagnards offer a compelling study in the challenges of revolutionary change. Their story underscores the tension between idealism and pragmatism, between the pursuit of equality and the realities of power. While their legacy is complex, their contributions to democratic and social thought are undeniable. They remind us that true reform often requires boldness, even if it means navigating perilous paths. In studying the Montagnards, we find not just a historical footnote but a timeless lesson in the struggle for a more just society.

Understanding Strong Political Culture: Foundations, Impact, and Global Examples

You may want to see also

Jacobins: Influential club supporting revolutionary ideals, played key role in Reign of Terror

The Jacobins, formally known as the Society of Friends of the Constitution, emerged as one of the most influential political clubs during the French Revolution. Founded in 1789, this group initially gathered in the Dominican convent of Saint-Jacques in Paris, from which their name derives. What began as a moderate assembly of deputies from the Estates-General evolved into a radical force advocating for republicanism, popular sovereignty, and the overthrow of the monarchy. Their rise to prominence was swift, fueled by their ability to mobilize public opinion and their unwavering commitment to revolutionary ideals.

At the heart of the Jacobins' ideology was the belief in the sovereignty of the people and the necessity of a democratic republic. They championed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, viewing it as the cornerstone of a just society. However, their methods became increasingly extreme as the Revolution progressed. Led by figures like Maximilien Robespierre, Georges Danton, and Jean-Paul Marat, the Jacobins dominated the National Convention and orchestrated the Reign of Terror from 1793 to 1794. This period saw the execution of thousands deemed enemies of the Revolution, including King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, as well as many former allies of the Jacobins.

The Reign of Terror was both a manifestation of the Jacobins' revolutionary zeal and a reflection of their internal fractures. While they sought to purge France of counter-revolutionary elements, their tactics alienated moderates and sowed fear among the populace. The club's influence began to wane after Robespierre's execution in July 1794, marking the end of their dominance. Yet, their legacy endures as a cautionary tale about the dangers of unchecked radicalism and the complexities of revolutionary governance.

To understand the Jacobins' impact, consider their role in shaping modern political discourse. Their emphasis on popular sovereignty and equality laid the groundwork for democratic movements worldwide. However, their descent into authoritarianism highlights the fine line between revolutionary idealism and tyranny. For historians and political analysts, studying the Jacobins offers insights into the dynamics of revolutionary organizations and the challenges of balancing radical change with stability.

Practical takeaways from the Jacobins' story include the importance of accountability within political movements and the need for checks on power, even in times of crisis. Aspiring leaders and activists can learn from their rise and fall, recognizing that the pursuit of noble ideals must be tempered by pragmatism and respect for human rights. The Jacobins' legacy serves as a reminder that revolutions, while transformative, require careful stewardship to avoid devolving into chaos.

Understanding Political Actors: Key Players Shaping Global Policies and Decisions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cordeliers: Left-wing group, focused on popular sovereignty and rights of the poor

The Cordeliers Club, a radical left-wing group, emerged during the French Revolution as a vocal advocate for popular sovereignty and the rights of the impoverished. Formed in 1790, the club took its name from the former Cordeliers Convent in Paris, where it initially met. Unlike more moderate factions, the Cordeliers prioritized the demands of the sans-culottes—the urban working class—and pushed for direct democracy and economic equality. Their influence was felt most strongly during the Revolution’s most tumultuous phases, where they often acted as a bridge between the political elite and the streets.

At the heart of the Cordeliers’ ideology was the belief that political power should reside with the people, not just the bourgeoisie or nobility. They championed universal male suffrage, a radical idea at the time, and demanded that the National Assembly be held accountable to the will of the masses. Key figures like Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins used the club’s platform to mobilize public opinion, often through fiery speeches and pamphlets. Their newspaper, *Le Vieux Cordelier*, became a powerful tool for spreading their message, blending revolutionary fervor with practical calls for action.

The Cordeliers’ focus on the poor set them apart from other revolutionary factions. They advocated for measures like price controls on essential goods, public assistance for the unemployed, and the redistribution of wealth. During the food shortages of 1793, the club organized protests and petitions demanding the government address the crisis. Their slogan, “Du pain et la Constitution” (“Bread and the Constitution”), encapsulated their dual commitment to both political and economic rights. This populist approach earned them widespread support among the lower classes but also made them targets of suspicion from more conservative groups.

Despite their influence, the Cordeliers’ radicalism ultimately led to their downfall. As the Revolution grew more violent, the club’s association with figures like Danton, who was executed in 1794, tarnished its reputation. The Reign of Terror, which they initially supported, turned against them, and the club was disbanded in 1795. Yet, their legacy endures as a testament to the power of grassroots movements in shaping political change. The Cordeliers’ emphasis on popular sovereignty and social justice laid the groundwork for future left-wing ideologies, proving that even the most marginalized voices can drive revolutionary transformation.

Recruiting Political Candidates: Strategies and Processes of Party Selection

You may want to see also

Feuillants: Conservative faction, supported constitutional monarchy, opposed radical revolutionary measures

The Feuillants emerged in the tumultuous landscape of the French Revolution as a conservative counterbalance to the escalating radicalism of the Jacobins. Formed in 1791, primarily by members of the Club of 1789, this faction sought to preserve the gains of the Revolution while staunchly opposing its more extreme measures. Their name derived from the former monastery of the Feuillant order, where they initially convened, symbolizing their desire to anchor the Revolution in stability rather than chaos.

At the heart of the Feuillants’ ideology was their unwavering support for a constitutional monarchy. They viewed King Louis XVI not as an adversary but as a necessary figurehead for a functioning state. This stance set them apart from more radical groups like the Girondins and Jacobins, who increasingly saw the monarchy as an obstacle to true republicanism. The Feuillants’ commitment to the Constitution of 1791, which established a limited monarchy, reflected their belief in gradual reform over abrupt upheaval.

However, their conservatism extended beyond mere institutional loyalty. The Feuillants vehemently opposed radical revolutionary measures, such as the redistribution of land or the imposition of price controls. They feared that such policies would undermine property rights and economic stability, principles they held sacred. This opposition often pitted them against the growing populist sentiment, which demanded immediate relief for the impoverished masses. Their reluctance to embrace these demands alienated them from the common people, who increasingly viewed the Feuillants as out of touch.

The Feuillants’ political strategy was marked by pragmatism but also by a fatal misreading of the revolutionary tide. They sought alliances with moderate elements within the Legislative Assembly, hoping to steer the Revolution toward a more conservative outcome. Yet, their efforts were overshadowed by the escalating violence and polarization of the era. The failed flight of Louis XVI in 1791 and the subsequent radicalization of the populace further marginalized the Feuillants, who were increasingly seen as collaborators with the monarchy rather than champions of the Revolution.

By 1792, the Feuillants’ influence had waned significantly. Their inability to bridge the gap between conservative ideals and revolutionary realities rendered them irrelevant in the face of mounting radicalism. The rise of the Jacobins and the eventual execution of Louis XVI marked the end of their political aspirations. Yet, the Feuillants’ legacy endures as a testament to the complexities of the Revolution—a faction that sought to balance tradition with progress but ultimately succumbed to the forces of change. Their story serves as a cautionary tale about the challenges of moderation in times of extreme upheaval.

Mark Kelly's Political Affiliation: Unveiling His Party Membership

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The main political parties were the Jacobins, Girondins, Cordeliers, and the Montagnards, each representing different factions and ideologies during the Revolution.

The Jacobins were a radical republican group led by figures like Maximilien Robespierre. They advocated for democracy, social equality, and the execution of King Louis XVI, playing a central role in the Reign of Terror.

The Girondins were a more moderate faction of the Revolution, favoring a constitutional monarchy and opposing the execution of the king. They clashed with the Jacobins and were eventually purged during the Reign of Terror.

The Cordeliers Club was a radical populist group that included figures like Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins. They were known for their extreme revolutionary actions and played a key role in events like the storming of the Bastille.

The Montagnards, or "Mountain," were a radical left-wing group in the National Convention, including Jacobins and other extremists. They dominated the Convention during the Reign of Terror and were responsible for many of the Revolution's most drastic measures.