The early United States was marked by the emergence of political factions that laid the groundwork for the modern party system. Following the ratification of the Constitution in 1787, two dominant groups emerged: the Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, who advocated for a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain, and the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who championed states' rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal government. These early parties reflected deep ideological divides over the nation's future, with Federalists favoring a more elitist and urban vision, while Democratic-Republicans emphasized rural democracy and individual liberties. By the early 1800s, the Federalists declined, and the Democratic-Republicans became the dominant force, eventually splitting into the modern Democratic and Whig parties, which later evolved into the Republican Party.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Federalist Party | Founded in 1789, led by Alexander Hamilton, supported a strong central government, favored commerce and industry, and aligned with urban elites. |

| Democratic-Republican Party | Founded in 1792, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, advocated for states' rights, agrarian interests, and limited federal government. |

| Anti-Federalist Movement | Not a formal party but a coalition opposing the Federalist Party, emphasizing local control and individual liberties. |

| Whig Party (Early Version) | Briefly emerged in the 1790s, opposed to Federalist policies, but later dissolved; not the same as the mid-19th century Whig Party. |

| Ideological Focus | Federalists: Centralized power, national bank. Democratic-Republicans: States' rights, agrarian economy. |

| Key Figures | Federalists: Alexander Hamilton, John Adams. Democratic-Republicans: Thomas Jefferson, James Madison. |

| Geographic Support | Federalists: Strong in New England and urban areas. Democratic-Republicans: Dominant in the South and rural regions. |

| Major Policies | Federalists: National bank, Jay Treaty. Democratic-Republicans: Louisiana Purchase, reduction of federal debt. |

| Decline | Federalists declined after the War of 1812; Democratic-Republicans became dominant until the 1820s. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Federalist Party: Supported strong central government, led by Alexander Hamilton, influential in 1790s-1800s

- Democratic-Republican Party: Advocated states' rights, founded by Thomas Jefferson, dominated early 1800s

- Anti-Federalist Movement: Opposed Constitution ratification, emphasized local control, precursor to Democratic-Republicans

- Whig Party: Emerged in 1830s, supported economic modernization, later split over slavery

- Democratic Party: Formed in 1828, championed Jacksonian democracy, remains a major party today

Federalist Party: Supported strong central government, led by Alexander Hamilton, influential in 1790s-1800s

The Federalist Party, emerging in the 1790s, was a cornerstone of early American politics, advocating for a robust central government as the backbone of a stable and prosperous nation. Led by Alexander Hamilton, the party’s vision was shaped by the lessons of the Articles of Confederation, which had left the federal government weak and ineffective. Hamilton, as the first Secretary of the Treasury, championed policies like the establishment of a national bank, assumption of state debts, and the encouragement of manufacturing to solidify the nation’s economic and political unity. These initiatives were not merely theoretical; they were practical steps to ensure the young republic could compete on the global stage and avoid the fragmentation that had plagued the Confederation era.

To understand the Federalist Party’s influence, consider its role in shaping the nation’s financial system. Hamilton’s *Report on Public Credit* (1790) proposed that the federal government assume state debts, a move that not only stabilized state economies but also created a unified national credit system. This bold policy, though controversial, demonstrated the Federalists’ commitment to a strong central authority capable of addressing national challenges. Critics, particularly Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, argued that such measures favored the elite and threatened states’ rights, but the Federalists countered that a weak government would doom the nation to chaos. This ideological clash laid the groundwork for the first party system in the U.S., with Federalists and Democratic-Republicans representing opposing visions of governance.

The Federalists’ influence extended beyond economics into foreign policy and domestic order. During the 1790s, the party supported neutrality in the conflict between France and Britain, culminating in the Jay Treaty of 1794, which averted war with Britain but alienated France. Domestically, the Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition Acts (1798) to suppress dissent, a move that, while aimed at maintaining stability, sparked widespread criticism and ultimately weakened their popularity. These actions highlight the party’s prioritization of order over individual liberties, a stance that resonated with urban merchants and elites but alienated farmers and the growing frontier population.

Despite their decline after the election of 1800, the Federalists’ legacy endures in the institutions they helped establish. The national bank, a cornerstone of Hamilton’s vision, laid the foundation for the modern Federal Reserve. Their emphasis on a strong central government also influenced the interpretation of the Constitution, particularly through the elastic clause, which allowed Congress to undertake actions “necessary and proper” to execute its powers. While the party disbanded by the 1820s, its ideas continued to shape American governance, serving as a counterpoint to the states’ rights arguments of the Democratic-Republicans.

In practical terms, the Federalist Party’s approach offers a lesson in balancing central authority with regional autonomy. For modern policymakers, their example underscores the importance of creating institutions that can address national challenges without stifling local innovation. While their methods were not without flaws, the Federalists demonstrated that a strong federal government is essential for economic stability, national security, and the cohesion of a diverse republic. Their story reminds us that the tension between centralization and decentralization remains a defining feature of American political discourse.

Augusto Pinochet's Political Affiliation: Unraveling His Authoritarian Regime's Party Ties

You may want to see also

Democratic-Republican Party: Advocated states' rights, founded by Thomas Jefferson, dominated early 1800s

The Democratic-Republican Party, founded by Thomas Jefferson in the late 18th century, emerged as a powerful force in early American politics, shaping the nation’s trajectory during the early 1800s. At its core, the party championed states’ rights, a principle that directly opposed the Federalist Party’s emphasis on a strong central government. This ideological clash defined much of the political discourse of the era, with Democratic-Republicans arguing that individual states should retain sovereignty in most matters, limiting federal authority to a few essential functions. This stance resonated deeply with a populace wary of centralized power, particularly in the agrarian South and West, where local control was prized.

Jefferson’s leadership was instrumental in the party’s rise. His vision of a decentralized, agrarian republic stood in stark contrast to the Federalist vision of industrialization and urban growth. The Democratic-Republicans’ victory in the 1800 election, known as the "Revolution of 1800," marked a turning point, ending Federalist dominance and solidifying the party’s hold on power for nearly two decades. Key policies, such as the Louisiana Purchase and the reduction of the national debt, exemplified their commitment to expanding individual liberties and limiting federal intervention. However, their advocacy for states’ rights also sowed seeds of future conflict, as it often aligned with the protection of slavery in Southern states.

To understand the party’s appeal, consider its practical impact on everyday Americans. Farmers, who constituted the majority of the population, benefited from policies that reduced taxes and promoted land ownership. The party’s opposition to a national bank and tariffs further aligned with the interests of rural communities, though these stances occasionally clashed with the needs of emerging industrial centers. This focus on grassroots governance made the Democratic-Republicans a dominant force, but it also highlighted the tension between local autonomy and national unity—a tension that would later contribute to the party’s fragmentation.

Comparatively, the Democratic-Republicans’ approach to governance was both a strength and a limitation. While their emphasis on states’ rights fostered regional diversity and innovation, it also hindered the development of cohesive national policies. For instance, their resistance to federal infrastructure projects slowed economic integration, and their defense of states’ prerogatives often shielded practices like slavery from federal scrutiny. This duality underscores the party’s legacy: a champion of individual liberty and local control, yet complicit in the perpetuation of systemic inequalities.

In retrospect, the Democratic-Republican Party’s dominance in the early 1800s reflects the complexities of a young nation grappling with its identity. Their advocacy for states’ rights remains a cornerstone of American political thought, influencing debates on federalism to this day. Yet, their inability to reconcile regional differences with national unity serves as a cautionary tale. For modern readers, the party’s history offers a practical lesson: balancing local autonomy with collective progress is essential for a functioning democracy. By studying their rise and eventual decline, we gain insights into the enduring challenges of governance and the delicate art of political compromise.

Texas Politics: Unraveling the Lone Star State's Dominant Political Hue

You may want to see also

Anti-Federalist Movement: Opposed Constitution ratification, emphasized local control, precursor to Democratic-Republicans

The Anti-Federalist movement emerged as a critical force during the formative years of the United States, staunchly opposing the ratification of the Constitution. Their resistance was rooted in a deep skepticism of centralized authority, fearing it would undermine the sovereignty of individual states. Unlike their Federalist counterparts, who championed a strong federal government, Anti-Federalists prioritized local control, believing it to be the cornerstone of liberty and self-governance. This ideological divide was not merely a political disagreement but a fundamental clash over the nation’s future structure.

At the heart of the Anti-Federalist argument was the belief that a powerful central government would inevitably encroach upon individual freedoms and state rights. They warned that the Constitution, as written, lacked explicit protections for personal liberties, a concern later addressed by the addition of the Bill of Rights. Anti-Federalists, often representing rural and agrarian interests, feared that urban and commercial elites would dominate the new federal system, marginalizing the voices of ordinary citizens. Their emphasis on local governance was both a practical and philosophical stance, reflecting a distrust of distant, centralized power.

The movement’s influence extended beyond its immediate opposition to the Constitution. Anti-Federalists laid the groundwork for the Democratic-Republican Party, led by figures like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, who initially shared their concerns about federal overreach. While Madison eventually became a key architect of the Constitution, his early alignment with Anti-Federalist principles highlights the movement’s enduring impact. The Democratic-Republicans adopted many Anti-Federalist ideas, including a commitment to states’ rights and a suspicion of concentrated power, shaping early American political discourse.

Understanding the Anti-Federalist movement requires recognizing its role as a precursor to modern debates about federalism and individual rights. Their insistence on local control and skepticism of centralized authority resonate in contemporary discussions about the balance of power between state and federal governments. While their immediate goal of preventing Constitution ratification failed, their legacy endures in the political and legal frameworks that prioritize checks on federal power and the protection of individual liberties. The Anti-Federalists remind us that dissent is not merely opposition but a vital force in shaping a nation’s identity.

The Unexpected Courtesy of Bane: Exploring His Polite Demeanor

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Whig Party: Emerged in 1830s, supported economic modernization, later split over slavery

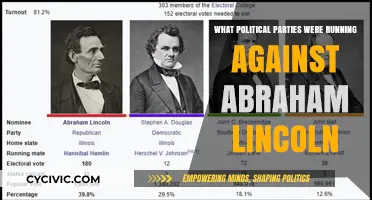

The Whig Party, emerging in the 1830s, was a pivotal force in early American politics, championing economic modernization as its core principle. Born in opposition to President Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party, Whigs advocated for a strong federal government to foster infrastructure, education, and industrial growth. They supported internal improvements like roads, canals, and railroads, believing these would unite the nation and drive prosperity. This vision contrasted sharply with Jacksonian Democrats, who favored states’ rights and limited federal intervention. Whigs also promoted a national bank and protective tariffs to shield American industries from foreign competition, appealing to entrepreneurs, merchants, and urban workers. Their platform reflected the aspirations of a nation transitioning from agrarian roots to an industrial future.

However, the Whig Party’s focus on economic progress was overshadowed by the growing divide over slavery. As the 1840s and 1850s unfolded, the issue of slavery’s expansion into new territories fractured the party. Northern Whigs increasingly opposed the spread of slavery, while Southern Whigs, tied to the region’s agrarian economy, defended it. This ideological rift was exacerbated by legislative battles like the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which forced Whigs to confront their internal contradictions. The party’s inability to reconcile these differences ultimately led to its dissolution, with members defecting to new parties like the Republicans and the American (Know-Nothing) Party.

To understand the Whigs’ downfall, consider their structural weaknesses. Unlike the Democrats, who had a broad base of support, the Whigs were a coalition of disparate interests—Northern industrialists, Southern planters, and anti-Jackson reformers. This diversity made it difficult to maintain unity on contentious issues. For instance, while Northern Whigs aligned with abolitionist sentiments, Southern Whigs prioritized regional economic stability, which relied on enslaved labor. The party’s leaders, including Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, struggled to bridge this gap, often resorting to vague or contradictory stances on slavery.

Practical takeaways from the Whig Party’s trajectory are clear: political coalitions must address fundamental ideological divides to survive. Modern parties can learn from the Whigs’ failure by prioritizing internal coherence and clear policy stances, especially on polarizing issues. For historians and political analysts, the Whigs offer a case study in the challenges of balancing regional interests and moral imperatives. Their story underscores the fragility of political alliances built on expediency rather than shared principles.

In retrospect, the Whig Party’s legacy is both a cautionary tale and a testament to the complexities of early American politics. While their economic vision laid the groundwork for the nation’s industrial rise, their inability to confront slavery head-on sealed their fate. The Whigs remind us that progress and unity are intertwined—and that ignoring deep-seated divisions can unravel even the most ambitious political movements. Their rise and fall serve as a timeless lesson in the interplay of ideals, interests, and the enduring struggle for consensus.

Louisiana's Governor: Unveiling the Political Party Affiliation in 2023

You may want to see also

Democratic Party: Formed in 1828, championed Jacksonian democracy, remains a major party today

The Democratic Party, born in 1828, emerged as a champion of Jacksonian democracy, a political philosophy that emphasized the power of the common man and the expansion of suffrage. This party, rooted in the ideals of Andrew Jackson, sought to challenge the elitism of the National Republicans and their predecessors, the Federalists. By advocating for the rights of the average citizen, the Democrats quickly gained popularity, particularly among farmers, workers, and immigrants. Their platform, which included opposition to centralized banking and support for states’ rights, resonated with a diverse electorate, laying the foundation for their enduring presence in American politics.

To understand the Democratic Party’s longevity, consider its adaptability. Unlike some early parties that faded into obscurity, the Democrats evolved with the nation’s changing demographics and issues. For instance, while their early focus on Jacksonian democracy emphasized individual liberty and limited federal government, they later embraced progressive reforms in the early 20th century, such as labor rights and social welfare programs. This ability to reinvent themselves allowed them to remain relevant across centuries, from the age of westward expansion to the era of civil rights and beyond.

A key takeaway from the Democratic Party’s history is the importance of aligning with the aspirations of the electorate. In 1828, they capitalized on the growing discontent with political and economic elites, positioning themselves as the party of the people. Today, they continue to appeal to a broad coalition, including minorities, urban dwellers, and younger voters, by addressing contemporary issues like healthcare, climate change, and economic inequality. This strategic responsiveness to societal shifts is a practical lesson for any political organization aiming to endure.

Comparatively, the Democratic Party’s survival contrasts sharply with the fate of the Whig Party, their primary rival in the mid-19th century. While the Whigs collapsed over internal divisions on slavery and other issues, the Democrats managed to navigate similar controversies, albeit with significant challenges. Their ability to absorb and adapt to ideological fractures, such as during the Civil War and the civil rights movement, highlights their resilience. This comparative analysis underscores the value of flexibility and inclusivity in maintaining a major party’s viability.

For those studying early U.S. political parties, the Democratic Party offers a unique case study in sustainability. Start by examining their founding principles in the context of Jacksonian democracy, then trace their evolution through key historical periods. Pay attention to how they responded to crises, such as the Great Depression or the 1960s cultural revolution, as these moments reveal their strategic priorities. Finally, compare their trajectory to that of defunct parties to identify the factors that contribute to long-term political survival. This approach provides actionable insights into the mechanics of enduring political organizations.

The Warhawks' Political Party: Uncovering Their Historical Affiliation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The first political parties in the early USA were the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. The Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, supported a strong central government, while the Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, advocated for states' rights and agrarian interests.

The key leaders of the Federalist Party included Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and George Washington (though he was not formally affiliated with any party). They promoted industrialization, a national bank, and a strong executive branch.

The Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, believed in limited federal government, states' rights, agrarianism, and strict interpretation of the Constitution. They opposed the Federalist Party's centralizing policies.

The rivalry between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans defined early American politics, setting the stage for the two-party system. Their debates over the role of government, economic policies, and foreign relations influenced the nation's development and the creation of key institutions like the national bank.