In 1796, the United States witnessed the emergence of its first formal political parties, marking a significant shift in American politics. The Federalist Party, led by figures such as Alexander Hamilton and John Adams, advocated for a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain. In opposition, the Democratic-Republican Party, spearheaded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, championed states' rights, agrarian interests, and a more limited federal government. These parties crystallized during the contentious presidential election of 1796, where Federalist John Adams narrowly defeated Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson, setting the stage for decades of partisan rivalry and shaping the nation's political landscape.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Year Founded | 1796 |

| Country of Origin | United States |

| Political Parties | Federalist Party, Democratic-Republican Party |

| Founding Leaders | Federalist: Alexander Hamilton, Democratic-Republican: Thomas Jefferson |

| Ideology (Federalist) | Strong central government, pro-business, close ties with Britain |

| Ideology (Democratic-Republican) | States' rights, agrarianism, opposition to centralized power, pro-France |

| Key Issues | National bank, taxation, foreign policy, interpretation of the Constitution |

| First President | Federalist: John Adams (1797–1801) |

| First Opposition Leader | Democratic-Republican: Thomas Jefferson (elected in 1800) |

| Historical Context | Emerged during George Washington's presidency, post-Revolutionary War era |

| Legacy | Laid the foundation for the two-party system in American politics |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Federalist Party: Supported strong central government, led by Alexander Hamilton, dominated early U.S. politics

- Democratic-Republican Party: Founded by Thomas Jefferson, advocated states' rights and agrarian interests

- Party Founders: Key figures like Hamilton and Jefferson shaped early American political divisions

- Ideological Split: Federalists vs. Democratic-Republicans reflected debates over government power and economy

- Election: First contested presidential election, showcasing the new party system in action

Federalist Party: Supported strong central government, led by Alexander Hamilton, dominated early U.S. politics

The Federalist Party, emerging in the crucible of post-Revolutionary America, was a political force shaped by the vision of Alexander Hamilton. Its creation in 1796 was not merely a response to the era’s political vacuum but a deliberate effort to establish a strong central government capable of steering the young nation toward stability and prosperity. Hamilton, as the party’s intellectual architect, believed that a robust federal authority was essential to prevent the fragmentation and economic chaos that had plagued the states under the Articles of Confederation. This party’s formation marked a pivotal moment in American political history, setting the stage for the nation’s early governance and ideological battles.

Hamilton’s leadership was instrumental in defining the Federalist Party’s agenda. He championed policies such as the establishment of a national bank, the assumption of state debts by the federal government, and the promotion of manufacturing and commerce. These measures were designed to create a cohesive economic framework that would bind the states together under federal oversight. The Federalists’ emphasis on a strong central government was not just economic but also reflected their commitment to maintaining order and ensuring the nation’s survival in a world dominated by European powers. Their vision, though often criticized as elitist, laid the groundwork for many of the institutions that continue to shape American governance today.

The Federalist Party’s dominance in early U.S. politics was both a testament to its organizational prowess and a reflection of the anxieties of the time. In the 1796 presidential election, Federalist candidate John Adams narrowly defeated Thomas Jefferson, signaling the party’s ability to mobilize support across the fledgling nation. However, this dominance was not without controversy. The Federalists’ support for the Alien and Sedition Acts, which restricted civil liberties in the name of national security, alienated many Americans and sowed the seeds of opposition. Despite these missteps, the party’s influence during its heyday was undeniable, shaping policies that would define the nation’s trajectory for decades.

A comparative analysis of the Federalist Party reveals its unique position in the early American political landscape. Unlike the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Jefferson, which advocated for states’ rights and agrarian interests, the Federalists prioritized national unity and economic modernization. This ideological divide mirrored broader tensions between urban and rural America, centralization and decentralization, and the role of government in citizens’ lives. While the Federalists’ influence waned after 1800, their legacy endures in the enduring debate over the balance of power between the federal government and the states.

For those studying early American politics, understanding the Federalist Party offers practical insights into the challenges of nation-building. Hamilton’s emphasis on a strong central government was not merely theoretical but a pragmatic response to the realities of the time. Modern policymakers can draw lessons from the Federalists’ successes and failures, particularly in balancing national interests with individual freedoms. By examining their policies and strategies, one gains a deeper appreciation for the complexities of governance and the enduring relevance of their ideas in contemporary political discourse.

Exploring Cuba's Political Landscape: Are There Multiple Parties?

You may want to see also

Democratic-Republican Party: Founded by Thomas Jefferson, advocated states' rights and agrarian interests

The Democratic-Republican Party, founded in 1796 by Thomas Jefferson, emerged as a direct response to the Federalist Party’s centralizing policies. Jefferson, alongside James Madison, crafted a platform that championed states’ rights, fearing that unchecked federal power would undermine individual liberties and local governance. This party’s creation marked a pivotal moment in American political history, as it introduced a two-party system that would define the nation’s ideological debates for decades. By advocating for decentralized authority, the Democratic-Republicans sought to protect the sovereignty of states and the autonomy of citizens, a stance that resonated deeply with agrarian communities.

At the heart of the Democratic-Republican Party’s ideology was its commitment to agrarian interests. Jefferson idealized the yeoman farmer as the backbone of American democracy, believing that an economy rooted in agriculture fostered independence and virtue. This vision contrasted sharply with the Federalist emphasis on commerce and industry. The party’s policies, such as opposition to the national bank and support for land expansion, were designed to benefit rural populations. For instance, the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, championed by Jefferson, provided vast new territories for farming, aligning perfectly with the party’s agrarian focus. This practical approach to governance ensured that the party’s principles were not merely theoretical but had tangible benefits for its constituents.

A comparative analysis reveals the Democratic-Republican Party’s unique position in the political landscape of 1796. While the Federalists favored a strong central government, tariffs, and close ties with Britain, the Democratic-Republicans championed states’ rights, low tariffs, and closer relations with France. This ideological divide reflected broader societal tensions between urban commercial elites and rural agrarian populations. The party’s ability to mobilize support among farmers and frontier settlers highlights its strategic understanding of demographic trends. By framing their policies as a defense of the common man against aristocratic tendencies, the Democratic-Republicans effectively differentiated themselves from their Federalist rivals.

To understand the Democratic-Republican Party’s legacy, consider its enduring influence on American political thought. Its emphasis on states’ rights and limited federal government laid the groundwork for future movements, including modern conservatism and libertarianism. Practical tips for studying this party include examining primary sources like Jefferson’s writings and Madison’s contributions to *The Federalist Papers*, which provide insight into their motivations. Additionally, analyzing the party’s role in key events, such as the Election of 1800, demonstrates how its principles shaped early American governance. By focusing on these specifics, one can grasp the party’s significance beyond its founding year.

In conclusion, the Democratic-Republican Party’s advocacy for states’ rights and agrarian interests was not merely a reaction to Federalist policies but a deliberate vision for America’s future. Its creation in 1796 introduced a counterbalance to central authority, ensuring that diverse voices within the young nation were heard. This party’s legacy reminds us of the importance of balancing federal and state powers, a debate that remains relevant today. By studying its origins and impact, we gain valuable insights into the foundations of American democracy and the enduring struggle between competing ideologies.

Who is Melanie Zanona? Unveiling Politico's Rising Star Reporter

You may want to see also

Party Founders: Key figures like Hamilton and Jefferson shaped early American political divisions

The emergence of political parties in 1796 was no accident—it was the culmination of ideological battles waged by titans like Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson. Hamilton, as the architect of the Federalist Party, championed a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain. Jefferson, in contrast, founded the Democratic-Republican Party to advocate for states’ rights, agrarianism, and alignment with France. Their clashing visions didn’t just define their parties; they etched the fault lines of American politics for decades.

Consider the practical implications of their rivalry. Hamilton’s financial policies, such as the national bank and assumption of state debts, were designed to stabilize the economy but alienated Southern planters who saw them as favoring Northern merchants. Jefferson’s counterargument—that centralized power threatened individual liberty—resonated deeply in rural areas. These weren’t abstract debates; they shaped policies like taxation, infrastructure, and foreign alliances. For instance, Hamilton’s push for tariffs to fund manufacturing directly opposed Jefferson’s ideal of a self-sufficient agrarian society.

To understand their impact, imagine early America as a laboratory of ideas. Hamilton’s Federalists were the pragmatists, prioritizing economic growth and order. Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans were the idealists, warning against corruption and tyranny. Their disagreements weren’t just about policy—they were about identity. Federalists attracted urban elites, while Democratic-Republicans rallied farmers and frontier settlers. This divide wasn’t merely ideological; it was geographic, economic, and cultural.

Here’s a practical takeaway: study their methods of persuasion. Hamilton used reports, like his *Report on Manufactures*, to make complex ideas accessible to lawmakers. Jefferson leveraged newspapers and personal correspondence to build grassroots support. Both understood the power of communication in shaping public opinion. Modern political strategists could learn from their ability to frame issues in ways that resonated with their bases.

In conclusion, Hamilton and Jefferson weren’t just party founders—they were architects of American political culture. Their legacies remind us that parties aren’t just vehicles for power; they’re expressions of competing visions for society. By examining their strategies and principles, we gain insights into how ideological differences can both divide and define a nation. Their story isn’t just history; it’s a blueprint for understanding political polarization today.

Launching a Political Party: A Step-by-Step State Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$26.21 $39.95

$19.08 $34.5

Ideological Split: Federalists vs. Democratic-Republicans reflected debates over government power and economy

The emergence of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties in 1796 marked a pivotal ideological split in American politics, rooted in contrasting visions of government power and economic policy. Federalists, led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, championed a strong central government as essential for national stability and economic growth. They advocated for a national bank, protective tariffs, and federal subsidies for manufacturing, viewing these measures as critical to fostering a robust economy. In contrast, Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, feared centralized power as a threat to individual liberties and states’ rights. They idealized an agrarian economy, emphasizing the virtues of small farmers and local control. This divide was not merely philosophical; it shaped the nation’s trajectory, influencing everything from fiscal policy to the interpretation of the Constitution.

Consider the economic policies proposed by each party as a case study in their differing ideologies. Federalists pushed for Hamilton’s financial system, which included federal assumption of state debts and the establishment of a national bank. These policies aimed to create a unified credit system and encourage industrial development. Democratic-Republicans, however, saw such measures as favoring the wealthy elite at the expense of the common man. They opposed the national bank and tariffs, arguing they burdened farmers and small businesses. This clash over economic policy reflected deeper disagreements about the role of government: should it actively intervene to promote national prosperity, or should it remain limited to protect individual freedoms?

To understand the practical implications of this split, examine the parties’ stances on foreign policy. Federalists favored closer ties with Britain, believing trade and diplomatic alignment with a global power would strengthen the young nation. Democratic-Republicans, on the other hand, sympathized with revolutionary France, viewing it as a kindred spirit in the fight against monarchy. This divergence was not just about alliances; it symbolized differing attitudes toward government authority. Federalists prioritized stability and order, even if it meant aligning with established powers, while Democratic-Republicans championed the ideals of liberty and self-determination, even if it risked instability.

A persuasive argument can be made that this ideological split laid the groundwork for modern political debates. The Federalist emphasis on federal power and economic intervention foreshadowed later progressive and conservative movements, while the Democratic-Republican focus on limited government and individual rights resonates with libertarian and populist ideologies. By studying this early divide, we gain insight into recurring themes in American politics: the tension between collective welfare and personal freedom, the role of government in economic development, and the balance between national unity and local autonomy.

In practical terms, this split offers a framework for analyzing contemporary issues. For instance, debates over federal spending, taxation, and regulation often echo the Federalist-Democratic-Republican divide. To apply this historically informed perspective, consider the following steps: first, identify the core principles at stake in a policy debate (e.g., government intervention vs. individual liberty). Second, trace these principles back to their 18th-century roots. Finally, evaluate how historical precedents might inform current decisions. By doing so, we can navigate modern political challenges with a deeper understanding of their ideological underpinnings.

Understanding Urban Political Economy: Power, Policy, and City Development

You may want to see also

1796 Election: First contested presidential election, showcasing the new party system in action

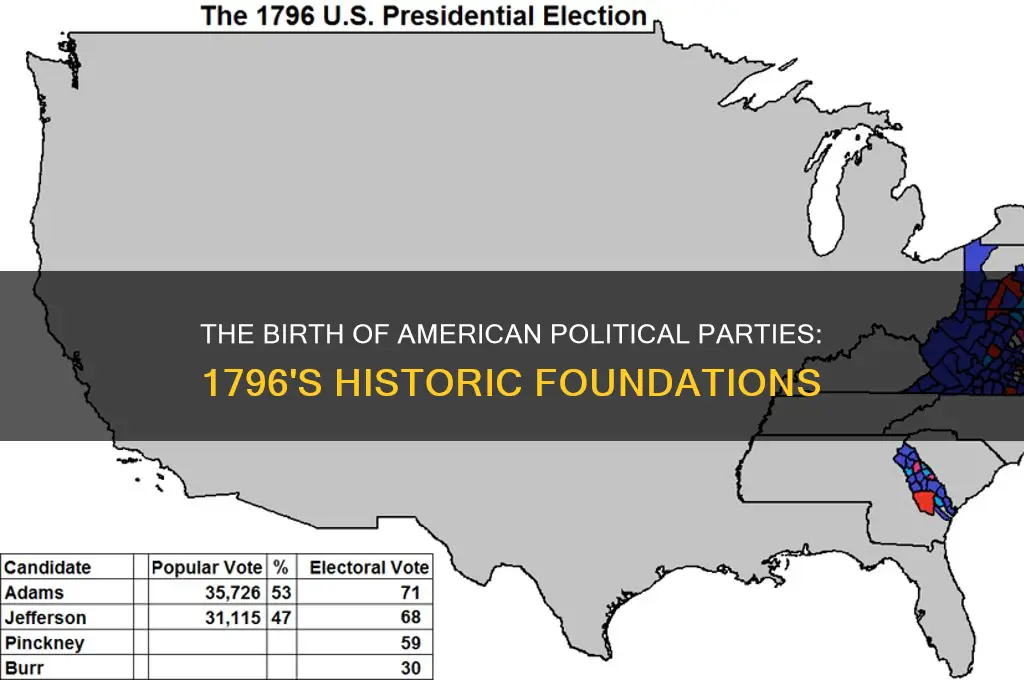

The 1796 U.S. presidential election stands as a pivotal moment in American political history, marking the first time the nation witnessed a truly contested race between emerging political parties. This election not only solidified the two-party system but also set the stage for future campaigns, introducing tactics and issues that remain relevant today. At its core, the contest between Federalist John Adams and Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson highlighted the ideological divide shaping the young republic.

Consider the backdrop: the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, championed a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain. In contrast, Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans advocated for states’ rights, agrarian interests, and alignment with France. These competing visions transformed the election into a referendum on the nation’s future direction. Campaigning, though less overt than modern standards, involved newspapers, pamphlets, and public speeches, with each side painting the other as a threat to liberty. For instance, Federalists warned of Jefferson’s radicalism, while Democratic-Republicans accused Adams of monarchical tendencies.

The mechanics of the election reveal the flaws of the original electoral system. Electors cast two votes, with the highest vote-getter becoming president and the runner-up vice president. This design, intended to foster unity, instead produced an awkward outcome: Adams won the presidency, while Jefferson, his ideological opponent, became vice president. This unintended consequence underscored the need for reform, leading to the 12th Amendment in 1804. Practical tip: Understanding this system helps explain why early elections often paired rivals, a stark contrast to today’s unified tickets.

Analytically, the 1796 election serves as a case study in party polarization. The Federalists and Democratic-Republicans not only disagreed on policy but also framed their opposition as a battle for the soul of the nation. This dynamic persists in modern politics, where parties often define themselves in opposition to one another. Comparative analysis shows that while issues have evolved, the structure of partisan conflict remains rooted in this foundational election. For example, debates over federal power versus states’ rights continue to shape contemporary policy discussions.

In conclusion, the 1796 election was more than a race between Adams and Jefferson; it was a demonstration of the new party system in action. By examining its mechanics, ideological clashes, and unintended outcomes, we gain insight into the origins of American political culture. This election reminds us that the challenges of partisanship and governance are not new but have been central to the nation’s identity from its earliest days.

Discover Your Catalan Political Party Match: A Comprehensive Alignment Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The two main political parties created in 1796 were the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party.

The Federalist Party was led by Alexander Hamilton, while the Democratic-Republican Party was led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

The Federalist Party favored a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Great Britain, whereas the Democratic-Republican Party advocated for states' rights, agrarianism, and a more democratic government.

The creation of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties in 1796 marked the beginning of the First Party System in the United States, shaping the country's political landscape and setting the stage for the two-party system that continues to dominate American politics today.