While many political parties in the mid-19th century United States were deeply divided over the issue of slavery, the Free Soil Party stood out as a unified force against its expansion. Emerging in the 1840s, the Free Soil Party brought together diverse groups, including abolitionists, Whigs, and Democrats, who shared a common goal: preventing the spread of slavery into new territories. Unlike the Democratic and Whig parties, which were internally fractured by regional and ideological differences, the Free Soil Party maintained a consistent stance, advocating for free labor and opposing the extension of slavery. This unity, though short-lived, laid the groundwork for the eventual formation of the Republican Party, which would similarly prioritize the containment of slavery. Thus, the Free Soil Party serves as a notable example of a political entity that was not divided over the contentious issue of slavery.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Pre-1820s Political Unity: Early parties like Federalists, Democratic-Republicans avoided slavery as a central issue

- Whig Party Stance: Whigs focused on economic issues, not slavery, to maintain broad national support

- Know-Nothing Party: Focused on anti-immigration, avoiding slavery to appeal to both North and South

- Early Democratic Party: Before 1840s, Democrats prioritized states' rights, not slavery, as a unifying theme

- Constitutional Union Party: Formed in 1860 to avoid secession, ignoring slavery to preserve the Union

Pre-1820s Political Unity: Early parties like Federalists, Democratic-Republicans avoided slavery as a central issue

In the early years of the United States, political parties like the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans navigated a delicate balance, consciously avoiding slavery as a central issue. This strategic omission was not born of indifference but of necessity. The young nation, still consolidating its identity, faced the daunting task of uniting diverse states with varying economic interests. Slavery, deeply entrenched in the Southern agrarian economy, was a volatile topic that threatened to fracture the fragile union. By sidestepping this issue, early political parties prioritized national cohesion over ideological purity, a pragmatic choice that shaped the nation’s formative years.

Consider the Federalist Party, which dominated the 1790s and early 1800s. Led by figures like Alexander Hamilton, Federalists focused on economic development, centralized government, and industrial growth. While many Federalists personally opposed slavery, the party’s platform remained silent on the issue. This silence was strategic: alienating Southern states, which relied heavily on enslaved labor, could undermine the party’s broader goals. Similarly, the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson, emphasized states’ rights and agrarian interests. Despite Jefferson’s complex relationship with slavery as a slaveholder himself, the party avoided making it a defining issue. Both parties understood that openly confronting slavery risked destabilizing the political landscape, potentially leading to secession or civil unrest.

This avoidance of slavery as a central issue was not without consequences. By failing to address the moral and economic implications of slavery, early political parties inadvertently perpetuated its existence. The Missouri Compromise of 1820, which temporarily defused tensions by admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, was a direct result of this earlier silence. It highlighted the growing impossibility of sidestepping the issue as the nation expanded westward. Yet, in the pre-1820s era, this strategy of avoidance served its purpose, allowing the nation to grow and stabilize without being torn apart by the slavery question.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark contrast between this early unity and the later divisions that would define American politics. While the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties managed to avoid open conflict over slavery, their successors—the Whigs, Democrats, and later the Republicans—could not. The rise of abolitionism and the intensification of sectional tensions in the mid-19th century made slavery an inescapable issue. This shift underscores the unique context of the pre-1820s era, where political unity was maintained through deliberate silence rather than active resolution.

For modern observers, this historical period offers a cautionary tale about the limits of avoidance in addressing deeply divisive issues. While sidestepping contentious topics may provide temporary stability, it often delays inevitable confrontations. The early parties’ strategy bought time for the nation to grow, but it also sowed the seeds of future conflict. Understanding this dynamic can inform contemporary approaches to divisive issues, emphasizing the importance of proactive engagement over strategic silence. By studying this era, we gain insights into the complexities of political unity and the long-term consequences of unresolved moral dilemmas.

Understanding CF Politics: A Comprehensive Guide to Its Dynamics and Impact

You may want to see also

Whig Party Stance: Whigs focused on economic issues, not slavery, to maintain broad national support

The Whig Party, emerging in the 1830s, deliberately sidestepped the contentious issue of slavery, instead anchoring its platform on economic modernization. This strategic focus on internal improvements, such as railroads, canals, and public education, allowed Whigs to appeal to both Northern industrialists and Southern planters who shared an interest in economic growth. By avoiding the slavery debate, the party maintained a fragile national coalition, though this approach ultimately limited its ability to address the moral and political crisis of the era.

Consider the Whig Party’s legislative priorities, which included the establishment of a national bank and tariffs to protect American industries. These policies were designed to foster economic development across regions, offering something tangible to voters regardless of their stance on slavery. For instance, the 1840 presidential campaign of William Henry Harrison emphasized infrastructure projects like the Cumberland Road, which connected the East to the Midwest, rather than engaging with the divisive issue of slavery expansion. This economic focus was a calculated move to unite a diverse electorate.

However, this strategy had its limitations. While Whigs successfully attracted voters by focusing on economic issues, their refusal to take a clear stance on slavery left them vulnerable to criticism from both abolitionists and pro-slavery factions. The party’s inability to address the moral dimensions of slavery contributed to its decline in the 1850s, as the issue became increasingly central to American politics. The Whigs’ economic agenda, though ambitious, could not sustain a party in an era defined by the slavery question.

A practical takeaway for understanding the Whig Party’s approach is to view it as a case study in political pragmatism. By prioritizing economic unity over moral division, the Whigs achieved short-term success but failed to build a lasting foundation. This strategy offers a cautionary lesson for modern political parties: while economic issues can unite diverse groups, ignoring deeply held moral and social concerns risks long-term irrelevance. The Whigs’ focus on economic modernization remains a relevant example of the challenges of balancing unity and principle in a polarized political landscape.

Is Joe Manchin Switching Parties? Analyzing His Political Future

You may want to see also

Know-Nothing Party: Focused on anti-immigration, avoiding slavery to appeal to both North and South

The Know-Nothing Party, formally known as the American Party, emerged in the mid-19th century as a political force uniquely positioned to sidestep the divisive issue of slavery. While other parties, like the Whigs and Democrats, were deeply fractured along regional lines over the morality and legality of slavery, the Know-Nothings adopted a strategy of avoidance. Instead of engaging in the contentious debate, they focused on anti-immigration policies, particularly targeting Irish and German Catholic immigrants, whom they viewed as threats to American jobs, culture, and Protestant values. This narrow focus allowed the party to appeal to both Northerners and Southerners, who, despite their differences on slavery, shared concerns about the influx of immigrants. By steering clear of the slavery question, the Know-Nothings sought to create a unified platform that could bridge the growing sectional divide.

To understand the Know-Nothings' strategy, consider their rise during a period of intense political polarization. The 1850s were marked by the collapse of the Whig Party and the emergence of the Republican Party, both of which were deeply entangled in the slavery debate. The Know-Nothings, however, capitalized on a different set of anxieties. They campaigned on a platform of nativism, advocating for stricter naturalization laws, longer residency requirements for citizenship, and the exclusion of immigrants from public office. This approach resonated with voters who felt economically and culturally threatened by immigration but were weary of the endless debates over slavery. By focusing on anti-immigration policies, the party effectively sidestepped the issue that had paralyzed other political movements, offering a seemingly neutral ground for Northerners and Southerners alike.

However, the Know-Nothings' strategy was not without its limitations. While their anti-immigration stance allowed them to avoid the slavery debate, it also alienated significant portions of the electorate. Catholic immigrants and their allies viewed the party as bigoted and exclusionary, while others questioned the practicality of their policies. Moreover, the party's refusal to address slavery meant they had no clear stance on the most pressing moral and economic issue of the time. This lack of a comprehensive vision ultimately contributed to their decline. By 1856, the party's influence waned as the slavery question became impossible to ignore, and the nation moved closer to the Civil War. The Know-Nothings' attempt to appeal to both North and South by avoiding slavery proved to be a temporary solution in a deeply divided nation.

In retrospect, the Know-Nothing Party serves as a case study in political pragmatism and its limitations. Their focus on anti-immigration policies allowed them to temporarily unite Northern and Southern voters, but their refusal to engage with the slavery issue left them without a sustainable platform. For modern political movements, the Know-Nothings offer a cautionary tale: while avoiding divisive issues may provide short-term gains, it often fails to address the root causes of societal conflict. Parties that seek to bridge divides must confront, rather than circumvent, the fundamental questions of their time. The Know-Nothings' legacy reminds us that unity built on avoidance is fragile and ultimately untenable.

Understanding Political Parties: Policies, Platforms, and Their Impact on Governance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Early Democratic Party: Before 1840s, Democrats prioritized states' rights, not slavery, as a unifying theme

The early Democratic Party, before the 1840s, was a coalition united not by a stance on slavery but by a deep commitment to states' rights. This principle, rooted in Jeffersonian ideals, emphasized local control over federal authority. Democrats argued that the Constitution granted limited powers to the national government, leaving most decisions to the states. This philosophy resonated with voters across the North and South, creating a broad-based party that could appeal to diverse interests without directly addressing the divisive issue of slavery.

Consider the Democratic Party’s platform during this period. While slavery existed and was a contentious issue, it was not the central organizing theme for Democrats. Instead, they focused on issues like tariffs, internal improvements, and the expansion of democracy. For instance, Andrew Jackson’s presidency (1829–1837) highlighted states' rights in his battles against the Second Bank of the United States and his enforcement of the Indian Removal Act. These actions demonstrated a commitment to limiting federal power, which aligned with the party’s unifying theme. Slavery, though present, was a secondary concern, managed through compromises like the Missouri Compromise of 1820 rather than being a defining party issue.

To understand this dynamic, imagine the Democratic Party as a ship navigating turbulent political waters. The crew, representing diverse regions and interests, agreed on one thing: the captain (federal government) should not dictate every move. Instead, each section of the ship (states) had autonomy to steer its course. This metaphor illustrates how states' rights served as the party’s compass, guiding its direction while avoiding the rocky shoals of slavery debates. Practical examples include the Nullification Crisis of 1832–1833, where South Carolina asserted its right to nullify federal tariffs, a move supported by many Democrats as a defense of states' rights, not slavery.

However, this focus on states' rights had limitations. While it allowed the party to remain unified, it also deferred the slavery question, setting the stage for future conflicts. The party’s ability to prioritize states' rights over slavery was a tactical success in the short term but ultimately unsustainable. By the 1840s, the issue of slavery’s expansion into new territories forced Democrats to confront divisions they had previously avoided. This shift marked the end of the party’s ability to maintain unity solely through states' rights rhetoric.

In conclusion, the early Democratic Party’s emphasis on states' rights was a strategic choice that allowed it to transcend regional differences and avoid internal division over slavery. This approach, while effective in the pre-1840s era, could not indefinitely postpone the inevitable reckoning with the nation’s most contentious issue. Understanding this period offers valuable insights into how political parties can temporarily bridge divides through broad, unifying principles—but also highlights the risks of delaying confrontation with fundamental moral and political questions.

Why Maps Reflect Power, Borders, and Political Agendas

You may want to see also

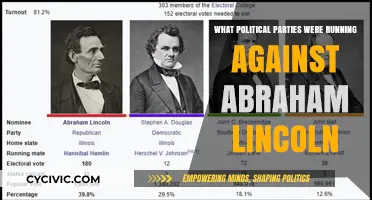

Constitutional Union Party: Formed in 1860 to avoid secession, ignoring slavery to preserve the Union

The Constitutional Union Party emerged in 1860 as a unique political entity, born out of the tumultuous pre-Civil War era. Unlike other parties of the time, it deliberately sidestepped the contentious issue of slavery, focusing instead on preserving the Union. This strategy, while seemingly pragmatic, reflected a deep-seated desire to avoid the ideological fractures that were tearing the nation apart. By prioritizing unity over moral or political stances on slavery, the party aimed to appeal to moderates in both the North and South who feared the consequences of secession.

To understand the Constitutional Union Party’s approach, consider it as a political triage effort. The nation was hemorrhaging from the slavery debate, and the party’s founders believed that addressing this issue would only exacerbate the bleeding. Their platform was straightforward: uphold the Constitution, maintain the Union, and defer the slavery question to future resolution. This was not a stance of indifference but a calculated decision to stabilize the country first. For instance, their 1860 convention in Baltimore adopted a single resolution: "The Constitution of the country, the Union of the States, and the Enforcement of the Laws." No mention of slavery, no moral judgments—just a call to preserve the nation’s integrity.

However, this strategy had its limitations. By ignoring slavery, the Constitutional Union Party failed to address the root cause of the nation’s division. Critics argue that this avoidance was shortsighted, as it did not provide a long-term solution to the moral and economic dilemmas posed by slavery. The party’s candidate, John Bell, won only three states in the 1860 election, all in the Upper South, highlighting the limited appeal of their platform. Yet, their effort remains a fascinating case study in political pragmatism, demonstrating the lengths to which some were willing to go to prevent the Union’s collapse.

Practical takeaways from the Constitutional Union Party’s approach can be applied to modern political conflicts. When polarization threatens to fracture a society, prioritizing unity over divisive issues may provide a temporary solution. However, such strategies must be accompanied by a commitment to addressing underlying problems. Ignoring contentious issues indefinitely only delays inevitable confrontations. For those seeking to navigate deeply divided landscapes, the Constitutional Union Party’s example serves as both a cautionary tale and a reminder of the delicate balance between stability and progress.

Decoding Political Party Leaning: Methods, Factors, and Determinants Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the Republican Party, founded in the 1850s, was largely unified in its opposition to the expansion of slavery into new territories.

No, the Whig Party was deeply divided over slavery, which contributed to its collapse in the 1850s.

No, the Free Soil Party was explicitly anti-slavery and united in its opposition to the expansion of slavery into Western territories.

The Know-Nothing Party, also known as the American Party, focused primarily on anti-immigration and nativist issues, avoiding a clear stance on slavery to maintain unity.

The Southern Democratic Party was largely unified in its defense of slavery, though there were minor factions that disagreed on specific aspects of its implementation.