Throughout U.S. history, the presidency has been dominated by the Democratic and Republican parties, but several other political parties have also been represented by presidents. The Federalist Party, led by figures like John Adams, held the presidency in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, while the Whig Party produced presidents such as William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor before its decline. The Democratic-Republican Party, founded by Thomas Jefferson, dominated the early 19th century, and the National Union Party, a temporary coalition during the Civil War, elected Abraham Lincoln to his second term. Additionally, the short-lived Federalist Party and the Progressive Party, under Theodore Roosevelt in 1912, further highlight the diversity of political affiliations that have reached the highest office, though their influence was often fleeting compared to the enduring dominance of the two major parties.

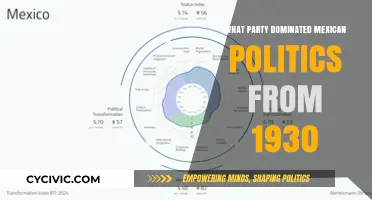

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| United States | Presidents have primarily been from the Democratic and Republican parties. Third-party or independent presidents have not been elected, though some ran (e.g., Ross Perot, Ralph Nader). |

| France | Presidents have represented major parties like La République En Marche! (LREM), The Republicans (LR), and the Socialist Party (PS). Smaller parties like the National Rally (RN) have gained prominence but not yet won the presidency. |

| Germany | Presidents are typically non-partisan, but they often have affiliations with major parties like the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), Social Democratic Party (SPD), or Free Democratic Party (FDP). |

| United Kingdom | Prime Ministers (not presidents) have been from the Conservative Party, Labour Party, and occasionally the Liberal Democrats. The UK does not have a presidential system. |

| India | Presidents are largely ceremonial and non-partisan, but they are often affiliated with major parties like the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) or the Indian National Congress (INC). |

| Brazil | Presidents have represented parties like the Workers' Party (PT), Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), and more recently, the Liberal Party (PL). |

| Mexico | Presidents have been from the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), National Action Party (PAN), and more recently, the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA). |

| Russia | Presidents have been from the United Russia party or independent, with strong ties to the ruling party. |

| South Africa | Presidents have been from the African National Congress (ANC), with no other party winning the presidency since the end of apartheid. |

| Canada | Prime Ministers (not presidents) have been from the Liberal Party, Conservative Party, and occasionally the New Democratic Party (NDP). Canada does not have a presidential system. |

| Australia | Prime Ministers (not presidents) have been from the Liberal Party, Australian Labor Party, and occasionally the National Party. Australia does not have a presidential system. |

| Japan | Prime Ministers (not presidents) have primarily been from the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), with occasional representation from the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ). Japan does not have a presidential system. |

| Italy | Presidents are largely ceremonial and non-partisan, but they often have affiliations with major parties like the Democratic Party (PD) or Forza Italia. |

| Argentina | Presidents have been from the Justicialist Party (PJ), Radical Civic Union (UCR), and more recently, the Republican Proposal (PRO). |

| South Korea | Presidents have been from the Democratic Party of Korea, People Power Party (formerly Liberty Korea Party), and occasionally smaller parties. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Democratic-Republican Party: Early 19th-century party, represented by presidents like Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe

- Whig Party: Mid-19th-century party, represented by presidents Harrison, Tyler, and Taylor

- Federalist Party: Late 18th-century party, represented by President John Adams

- Progressive Party: Early 20th-century party, represented by President Theodore Roosevelt

- Reform Party: Late 20th-century party, represented by President Donald Trump briefly

Democratic-Republican Party: Early 19th-century party, represented by presidents like Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe

The Democratic-Republican Party, a dominant force in early 19th-century American politics, shaped the nation’s trajectory through the leadership of presidents like Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe. Founded in opposition to the Federalist Party, this party championed states’ rights, limited federal government, and agrarian interests. Their ascendancy marked a shift from Federalist centralization, reflecting the ideological battles of the era. By examining their legacy, we gain insight into how early political parties defined the United’s States’ foundational principles.

Consider the party’s core tenets: Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase (1803) exemplified their expansionist vision, doubling the nation’s size while minimizing federal intervention in daily life. Madison’s stewardship during the War of 1812, though fraught with challenges, reinforced the party’s commitment to national sovereignty. Monroe’s eponymous doctrine (1823) asserted U.S. dominance in the Western Hemisphere, a policy that endures in foreign relations discourse. These actions illustrate how Democratic-Republicans balanced idealism with pragmatism, leaving a blueprint for future administrations.

To understand their impact, contrast their agrarian focus with the industrial leanings of later parties. While the Federalists favored manufacturing and urban growth, Democratic-Republicans prioritized farmers and rural economies. This divide mirrored broader societal tensions, such as the clash between Hamiltonian federalism and Jeffersonian democracy. For modern readers, this historical tension offers a lens to analyze contemporary debates over federal versus state authority, particularly in areas like healthcare or environmental policy.

A practical takeaway emerges: studying the Democratic-Republican Party reveals how early political ideologies continue to influence governance. For educators or history enthusiasts, tracing the party’s evolution—from its formation in the 1790s to its dissolution into the Democratic Party by the 1830s—provides a structured framework for understanding America’s political development. Pair this analysis with primary sources like Jefferson’s inaugural addresses or Madison’s Federalist Papers contributions for a richer, more nuanced exploration.

Finally, the Democratic-Republican Party’s dominance underscores the importance of ideological consistency in political leadership. Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe did not merely occupy the presidency; they embodied the party’s values, ensuring their policies reflected a unified vision. This cohesion contrasts with the fractious nature of some modern parties, offering a historical benchmark for evaluating political effectiveness. By dissecting their strategies, we learn how alignment between party principles and presidential action can shape a nation’s identity.

Steve Scully's Political Party Affiliation: Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Whig Party: Mid-19th-century party, represented by presidents Harrison, Tyler, and Taylor

The Whig Party, though short-lived, left an indelible mark on American politics during the mid-19th century, producing three presidents within a span of just over a decade. William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and Zachary Taylor each brought distinct leadership styles and priorities to the presidency, reflecting the Whig Party’s focus on economic modernization, internal improvements, and a strong federal role in fostering national growth. Their presidencies, however, were also marked by internal party divisions and the challenges of navigating a rapidly changing nation.

Consider the Whig Party’s rise as a response to the perceived failures of Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party. Whigs championed a program of active federal intervention to promote economic development, including support for infrastructure projects like roads and canals. This vision was embodied in the presidency of William Henry Harrison, whose 1840 campaign, though cut short by his untimely death after just 30 days in office, emphasized the Whigs’ commitment to progress and national unity. Harrison’s successor, John Tyler, however, proved a contentious figure within the party. Despite being a Whig, Tyler vetoed key Whig legislative priorities, earning him the nickname “His Accidency” and alienating his own party. This internal strife highlights the Whigs’ struggle to maintain cohesion in the face of diverse ideological currents.

Zachary Taylor, the third and final Whig president, represented a different facet of the party. A military hero with limited political experience, Taylor’s presidency was marked by his reluctance to take a strong stance on divisive issues like slavery. While he supported the admission of California as a free state, his cautious approach failed to satisfy either abolitionists or pro-slavery factions. Taylor’s sudden death in 1850 further destabilized the Whig Party, which was already grappling with the growing sectional tensions that would eventually lead to its dissolution.

To understand the Whigs’ legacy, examine their contributions to American political thought. They pioneered the concept of the federal government as an engine of economic growth, a philosophy that would later influence the Republican Party. However, their inability to resolve internal conflicts and address the issue of slavery underscores the fragility of their coalition. For modern readers, the Whig Party serves as a cautionary tale about the challenges of balancing diverse interests within a political organization, as well as the importance of clear, unified leadership in times of national crisis.

Practical takeaways from the Whigs’ experience include the need for political parties to articulate a coherent and adaptable platform, especially in a rapidly evolving society. Leaders must also be mindful of the risks of ideological rigidity, as seen in Tyler’s defiance of his own party. By studying the Whigs, one gains insight into the complexities of mid-19th-century American politics and the enduring lessons they offer for contemporary political movements.

John Holt's Political Beliefs: Unraveling His Ideological Stance and Influence

You may want to see also

Federalist Party: Late 18th-century party, represented by President John Adams

The Federalist Party, a pivotal force in late 18th-century American politics, stands as one of the earliest political parties to shape the nation’s governance. Founded by Alexander Hamilton, it championed a strong central government, industrialization, and close ties with Britain. Among its most notable representatives was President John Adams, whose tenure from 1797 to 1801 marked the party’s peak influence. Adams, though often overshadowed by his predecessor George Washington and successor Thomas Jefferson, embodied Federalist ideals in his policies, including the controversial Alien and Sedition Acts, which aimed to suppress dissent but sparked widespread backlash.

Analyzing the Federalist Party’s legacy reveals its dual nature: visionary yet divisive. While its emphasis on economic modernization laid the groundwork for America’s industrial future, its authoritarian tendencies alienated many. Adams’ presidency, in particular, highlights the party’s struggle to balance national unity with individual freedoms. The Quasi-War with France, for instance, demonstrated Federalist commitment to protecting American interests abroad but also exposed their willingness to expand executive power. This tension ultimately contributed to the party’s decline, as voters gravitated toward the Democratic-Republican Party’s emphasis on states’ rights and agrarianism.

To understand the Federalist Party’s impact, consider its role in shaping early American political discourse. It introduced the concept of a two-party system, setting a precedent for ideological competition. Practical takeaways include the importance of balancing central authority with local autonomy—a lesson still relevant in modern governance. For instance, policymakers today can learn from the Federalists’ focus on infrastructure and economic development while avoiding their overreach in civil liberties.

Comparatively, the Federalist Party’s trajectory contrasts sharply with later parties like the Whigs or Republicans, which evolved to address changing societal needs. Unlike the Federalists, these parties adapted their platforms to appeal to broader demographics, ensuring longevity. The Federalists’ rigid ideology, while influential, limited their appeal, particularly in an era of westward expansion and democratization. This comparison underscores the necessity of flexibility in political organizations.

Descriptively, the Federalist Party’s era was one of intellectual fervor and ideological clashes. Its leaders, including Adams, were products of the Enlightenment, valuing reason and order. Their vision of America as a commercial powerhouse clashed with Jeffersonian agrarianism, creating a cultural divide that persists in some form today. By examining this period, we gain insight into the enduring struggle between centralization and decentralization in American politics. The Federalist Party’s brief but impactful reign serves as a reminder of the complexities inherent in nation-building.

Rousseau's Political Philosophy: Freedom, Equality, and the Social Contract

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Progressive Party: Early 20th-century party, represented by President Theodore Roosevelt

The Progressive Party, often referred to as the "Bull Moose Party," emerged in the early 20th century as a response to the perceived failures of the major political parties in addressing pressing social and economic issues. Founded in 1912, it was a short-lived yet impactful third party that challenged the dominance of the Democratic and Republican parties. At its helm was former President Theodore Roosevelt, who sought to continue his progressive reforms after a falling out with his successor, William Howard Taft, and the Republican Party establishment.

Roosevelt’s decision to run for president under the Progressive Party banner in 1912 was a bold move, driven by his commitment to trust-busting, labor rights, women’s suffrage, and conservation. His platform, known as the "New Nationalism," advocated for federal regulation of corporations, social welfare programs, and environmental protection. The party’s convention in Chicago was a spectacle of democracy, with delegates from diverse backgrounds, including women and minorities, participating in a way that was unprecedented for its time. Roosevelt’s campaign energized voters, but it also split the Republican vote, ultimately helping Democrat Woodrow Wilson win the presidency.

Despite its failure to secure the White House, the Progressive Party’s influence on American politics cannot be overstated. It pushed both major parties to adopt progressive reforms, such as the Federal Reserve System, the Clayton Antitrust Act, and the eventual passage of the 19th Amendment. Roosevelt’s candidacy demonstrated the power of third parties to shape national agendas, even if they do not win elections. His leadership of the Progressive Party remains a testament to the enduring appeal of progressive ideals in American politics.

For those interested in studying third-party movements, the Progressive Party offers a case study in both the potential and limitations of such efforts. While it failed to establish a lasting political organization, its ideas and policies left a lasting legacy. Practical takeaways include the importance of charismatic leadership, a clear and compelling platform, and the ability to mobilize grassroots support. Roosevelt’s example also highlights the risks of splitting the vote, a cautionary tale for modern third-party candidates.

In analyzing the Progressive Party, one must consider its historical context—a time of rapid industrialization, social inequality, and political corruption. Roosevelt’s ability to articulate a vision for a more just and equitable society resonated with millions of Americans. Today, as debates over economic inequality, corporate power, and environmental sustainability continue, the Progressive Party’s agenda remains strikingly relevant. Its story serves as a reminder that third parties, though often overlooked, can play a pivotal role in driving systemic change.

Piers Morgan's Political Leanings: Uncovering His Party Allegiance and Views

You may want to see also

Reform Party: Late 20th-century party, represented by President Donald Trump briefly

The Reform Party, a late 20th-century political entity, briefly captured national attention when Donald Trump, then a real estate mogul and television personality, affiliated with it in 1999. Founded in 1995 by Ross Perot, the party positioned itself as a centrist alternative to the dominant Democratic and Republican parties, emphasizing fiscal responsibility, campaign finance reform, and reducing the national debt. Trump’s involvement was short-lived but significant, as he explored a presidential bid under its banner, leveraging its ballot access in key states. This move highlighted the party’s appeal to independent-minded figures seeking to bypass the traditional two-party system.

Analytically, Trump’s association with the Reform Party underscores the challenges third parties face in American politics. Despite Perot’s strong showing as an independent candidate in 1992, the party struggled to sustain momentum. Trump’s brief affiliation was more strategic than ideological, as he later returned to the Republican Party, which offered a clearer path to power. This episode illustrates how third parties often serve as platforms for individual ambitions rather than vehicles for lasting political change. The Reform Party’s decline after 2000 further reinforces the structural barriers third parties encounter in a system designed to favor the two major parties.

Instructively, for those considering third-party involvement, the Reform Party’s trajectory offers key lessons. First, ballot access is critical; the party’s success in securing it in multiple states was a rare achievement for a third party. Second, a charismatic leader can temporarily boost visibility, as Trump did, but sustained growth requires a robust organizational structure and clear policy agenda. Finally, aligning with a third party demands careful consideration of its long-term viability. Trump’s pivot back to the GOP demonstrates the pragmatic realities of American politics, where third parties often function as stepping stones rather than destinations.

Persuasively, the Reform Party’s story challenges the notion that the two-party system is unassailable. While it ultimately failed to reshape the political landscape, it demonstrated the potential for third parties to influence national discourse. Trump’s brief involvement brought media attention to issues like campaign finance reform, even if his commitment was fleeting. This suggests that third parties, though often marginalized, can still play a role in pushing mainstream parties to address neglected concerns. Their impact may be indirect, but it is not insignificant.

Descriptively, the Reform Party’s brief moment in the spotlight was marked by both promise and paradox. It attracted figures like Trump and Perot, who embodied anti-establishment sentiment, yet it struggled to translate this into electoral success. Its conventions were lively affairs, blending populist rhetoric with policy proposals, but its grassroots support remained limited. The party’s logo, a bold eagle atop the word “Reform,” symbolized its aspirations, but its legacy is one of untapped potential. For a fleeting moment, it offered a glimpse of what American politics might look like beyond the red and blue divide.

Can Political Parties Legally Expel Members? Exploring Rules and Consequences

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The only other political party to have a president in the United States was the Whig Party, with presidents William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, and Zachary Taylor.

No, no third-party or independent candidate has ever been elected as president in the United States.

President Abraham Lincoln was a member of the Republican Party.

Yes, President John Tyler, originally elected as a Whig, effectively became an independent after being expelled from the Whig Party due to policy disagreements.

No, since the mid-19th century, all U.S. presidents have been affiliated with either the Democratic or Republican Party.