Political machines, which were prevalent in the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, were primarily associated with the Democratic Party, particularly in urban areas. These organizations, often led by powerful bosses, wielded significant influence over local and state politics by mobilizing voters, distributing patronage jobs, and controlling key political offices. While some Republican political machines existed, such as those in Philadelphia and Chicago, the Democratic Party’s dominance in cities like New York, Boston, and Tammany Hall made them the most notorious for this system of political control. Political machines were characterized by their ability to deliver services and favors in exchange for votes, blurring the lines between public service and corruption. Their legacy remains a critical aspect of understanding the evolution of American political parties and urban governance.

Explore related products

$20.41 $15.75

What You'll Learn

- Tammany Hall: Democratic Party machine in New York City, dominated local politics in the 19th century

- Cook County Democrats: Controlled Chicago politics, linked to the Democratic Party in Illinois

- Republican Machines: Operated in cities like Philadelphia, tied to the Republican Party

- Pendergast Machine: Democratic Party-aligned machine in Kansas City, led by Tom Pendergast

- Urban Party Alignment: Most machines were tied to either the Democratic or Republican Party

Tammany Hall: Democratic Party machine in New York City, dominated local politics in the 19th century

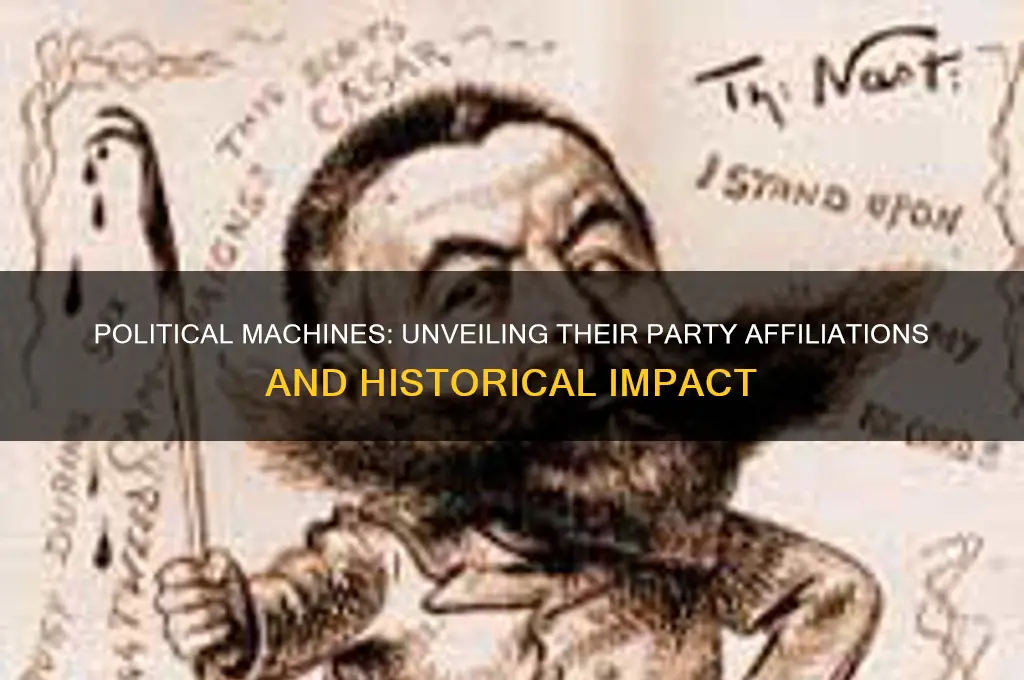

Tammany Hall, a name synonymous with political power and patronage, was the epicenter of the Democratic Party’s machine politics in 19th-century New York City. Operating from its headquarters in Manhattan, Tammany Hall wielded unparalleled influence over local elections, public appointments, and urban development. Its dominance was built on a simple yet effective strategy: trading favors for votes. By providing jobs, services, and protection to immigrants and the working class, Tammany Hall secured a loyal voter base that kept the Democratic Party in control. This system, while often criticized for corruption, was a masterclass in political organization and grassroots mobilization.

To understand Tammany Hall’s success, consider its structure as a well-oiled machine. At its core were the "bosses," influential figures like William M. Tweed, who controlled the distribution of resources and political appointments. Below them were precinct captains, local leaders responsible for delivering votes in their neighborhoods. This hierarchical system ensured that Tammany Hall could respond swiftly to the needs of its constituents, whether it was securing a job on the docks or resolving a landlord dispute. For example, during the mid-1800s, Tammany Hall provided critical support to Irish immigrants, earning their unwavering loyalty and solidifying the Democratic Party’s hold on power.

However, Tammany Hall’s methods were not without controversy. The machine’s reliance on patronage and graft led to widespread corruption, epitomized by the Tweed Ring’s embezzlement of millions from the city treasury. Investigative journalism and public outrage eventually brought down Tweed, but Tammany Hall persisted, adapting to new political realities. Its ability to survive scandals highlights a key takeaway: political machines thrive by balancing the needs of their constituents with the demands of power, often walking a fine line between service and exploitation.

Comparing Tammany Hall to other political machines of its time reveals both its uniqueness and its universality. While Republican machines in cities like Philadelphia and Chicago operated similarly, Tammany Hall’s focus on immigrant communities set it apart. Its leaders understood that New York’s demographic shifts required a tailored approach, and they capitalized on this by becoming champions of the marginalized. This adaptability is a lesson for modern political organizations: success often depends on recognizing and addressing the specific needs of diverse populations.

In practical terms, Tammany Hall’s legacy offers insights into the mechanics of political influence. For anyone studying or engaging in local politics, the machine’s strategies—building grassroots networks, leveraging patronage, and responding to constituent needs—remain relevant. However, its downfall also serves as a cautionary tale: transparency and accountability are essential to maintaining public trust. By examining Tammany Hall, we gain a nuanced understanding of how political machines operate and the delicate balance they must strike to endure.

Netanyahu's Political Party: Understanding Likud's Role in Israeli Politics

You may want to see also

Cook County Democrats: Controlled Chicago politics, linked to the Democratic Party in Illinois

The Cook County Democratic Party, a powerhouse in Illinois politics, has long been synonymous with political machine operations, particularly in Chicago. This organization, deeply intertwined with the Democratic Party at the state level, exemplifies how local political machines can dominate urban politics through a combination of patronage, organizational efficiency, and strategic alliances. By controlling key positions and resources, the Cook County Democrats have maintained their grip on Chicago’s political landscape for decades, shaping policies and elections in ways that reflect both their strengths and vulnerabilities.

Consider the mechanics of their influence: the Cook County Democratic Party operates through a network of ward committeemen, each responsible for mobilizing voters, distributing resources, and ensuring party loyalty. This system, while criticized for its lack of transparency, has proven remarkably effective in turning out votes and maintaining power. For instance, during election seasons, the machine’s ability to deliver services—such as job placements or neighborhood improvements—often hinges on voter turnout, creating a symbiotic relationship between the party and its constituents. This model, though not unique to Chicago, has been refined to an art form in Cook County, making it a case study in political machine dynamics.

However, the Cook County Democrats’ dominance is not without its challenges. Allegations of corruption, cronyism, and inefficiency have plagued the organization, raising questions about the sustainability of such political machines in an era of increasing transparency and accountability. High-profile scandals, such as those involving former Governor Rod Blagojevich, have tarnished the party’s reputation and forced it to adapt to changing public expectations. Yet, despite these setbacks, the machine’s resilience lies in its ability to evolve, incorporating new strategies while retaining its core structure.

A comparative analysis reveals that the Cook County Democrats’ success stems from their ability to balance local interests with broader Democratic Party goals. Unlike political machines in other cities, which often operate in isolation, the Cook County organization has maintained strong ties to the state and national Democratic Party, ensuring access to resources and influence beyond Chicago. This integration allows them to leverage federal and state funding for local projects, further solidifying their hold on power. For those studying political machines, this interplay between local and national politics offers valuable insights into how such organizations can thrive in a modern political environment.

In practical terms, understanding the Cook County Democratic Party’s operations can serve as a guide for both critics and proponents of political machines. For reformers, it highlights the need for systemic changes that address the root causes of corruption and inefficiency. For political strategists, it demonstrates the importance of grassroots organization and resource allocation in maintaining long-term control. Whether viewed as a cautionary tale or a blueprint for success, the Cook County Democrats’ story is a testament to the enduring power of political machines in American politics.

Stalin's Political Opponents: Key Figures Who Dared to Challenge His Rule

You may want to see also

Republican Machines: Operated in cities like Philadelphia, tied to the Republican Party

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Republican political machines wielded significant power in cities like Philadelphia, shaping local governance through a blend of patronage, voter mobilization, and strategic alliances. These machines were not merely extensions of the national Republican Party but localized power structures that adapted national ideologies to urban realities. By controlling key municipal offices, they distributed jobs, contracts, and favors in exchange for political loyalty, ensuring their dominance in city politics.

Consider the mechanics of these machines: they operated as hierarchical networks, with party bosses at the top and ward healers at the grassroots level. Ward healers, often neighborhood figures with deep community ties, acted as intermediaries between the machine and voters. Their role was to deliver votes during elections, resolve constituent issues, and maintain the machine’s influence through personal connections. In Philadelphia, for instance, Republican machines thrived by leveraging the city’s immigrant populations, offering them assistance with citizenship processes, employment, and social services in exchange for their support at the polls.

A critical aspect of Republican machines was their ability to bridge ideological gaps between the national party’s platform and local needs. While the national Republican Party often focused on business interests and fiscal conservatism, urban machines prioritized practical concerns like infrastructure, public safety, and job creation. This adaptability allowed them to maintain relevance in cities where national party policies might have otherwise alienated working-class voters. For example, Philadelphia’s Republican machine under figures like Boies Penrose ensured that the city’s growing industrial base received necessary investments, solidifying their hold on power.

However, the success of these machines came at a cost. Critics argued that their reliance on patronage fostered corruption, as public resources were often diverted to reward loyalists rather than serve the broader public. The lack of transparency in decision-making and the concentration of power in the hands of a few also undermined democratic principles. Despite these drawbacks, Republican machines in cities like Philadelphia demonstrated the effectiveness of localized political organization, leaving a lasting legacy in urban governance.

To understand the impact of Republican machines today, examine how modern political organizations replicate their strategies. While the overt patronage systems of the past have largely been dismantled, the emphasis on grassroots mobilization, voter turnout, and community engagement remains central to political success. For those studying political history or seeking to build effective campaigns, the Republican machines of Philadelphia offer a case study in the power of localized, relationship-driven politics—a reminder that even in an era of nationalized politics, local connections can still shape outcomes.

Becky Ames' Political Affiliation: Uncovering Her Party Allegiance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Pendergast Machine: Democratic Party-aligned machine in Kansas City, led by Tom Pendergast

The Pendergast Machine, a Democratic Party-aligned political machine in Kansas City during the early 20th century, exemplifies how local power structures can shape urban politics. Led by Tom Pendergast, this machine wielded immense influence through a network of patronage, graft, and strategic alliances. By controlling jobs, contracts, and even law enforcement, Pendergast ensured loyalty from constituents and dominance in local elections. His machine became a cornerstone of Democratic power in Missouri, illustrating the symbiotic relationship between political machines and their affiliated parties.

To understand the Pendergast Machine’s success, consider its operational blueprint. Pendergast began by consolidating control over Kansas City’s Democratic Party apparatus, using his construction business as a front for political deals. He rewarded supporters with government jobs, while opponents faced economic retaliation. For instance, during the Great Depression, Pendergast’s machine distributed relief funds selectively, securing votes in exchange for aid. This quid pro quo system, though ethically dubious, cemented his machine’s grip on power. Practical tip: When analyzing political machines, trace the flow of resources—jobs, contracts, and favors—to identify their power base.

A comparative lens reveals the Pendergast Machine’s uniqueness. Unlike Tammany Hall in New York, which catered to immigrants, Pendergast’s machine focused on urban workers and business elites. His alignment with the Democratic Party was strategic, leveraging federal programs like the New Deal to bolster his local influence. However, his machine’s corruption eventually led to his downfall, with Pendergast sentenced to prison in 1939 for tax evasion. This cautionary tale underscores the fragility of power built on illicit foundations.

Persuasively, the Pendergast Machine’s legacy challenges the notion that political machines are inherently detrimental. While corrupt, it delivered tangible benefits to Kansas City, including infrastructure projects and economic stability during a tumultuous era. For those studying political history, this duality prompts a critical question: Can the ends ever justify the means in politics? The Pendergast Machine’s Democratic alignment and operational tactics offer a rich case study for debating this dilemma.

Garth Brooks' Political Leanings: Uncovering His Party Affiliation and Views

You may want to see also

Urban Party Alignment: Most machines were tied to either the Democratic or Republican Party

Political machines, those often shadowy networks of influence and patronage, were not freestanding entities but deeply embedded within the fabric of America’s two-party system. Urban party alignment reveals a striking pattern: most machines were firmly tied to either the Democratic or Republican Party, their fates intertwined with the fortunes of these national organizations. This alignment was no accident. Cities, with their dense populations and diverse immigrant communities, became fertile ground for machine politics. The Democratic Party, in particular, dominated urban centers, leveraging its ability to deliver tangible benefits—jobs, housing, and protection—to working-class voters. Machines like Tammany Hall in New York City became synonymous with Democratic power, using their party affiliation to consolidate control over local and state governments.

Consider the mechanics of this alignment. Machines thrived by offering a quid pro quo: votes in exchange for favors. This system required a centralized party structure capable of distributing resources and enforcing loyalty. The Democratic and Republican Parties provided the necessary framework, with their committees, conventions, and electoral slates serving as conduits for machine influence. For instance, in Chicago, the Democratic machine under Mayor Richard J. Daley controlled everything from aldermanic elections to federal patronage appointments, ensuring the party’s dominance for decades. Republicans, while less dominant in urban areas, still fielded machines in cities like Philadelphia and Cincinnati, though their reach was often limited by the Democratic stronghold on immigrant and working-class votes.

The alignment with major parties also granted machines legitimacy and access to national resources. By aligning with the Democrats or Republicans, machines could tap into campaign funds, media support, and even federal programs. This symbiotic relationship allowed machines to amplify their local power while providing parties with reliable voting blocs in urban areas. However, this alignment was not without tension. Machines often prioritized local interests over national party platforms, leading to occasional conflicts with party leadership. Yet, the mutual benefits of this partnership ensured its endurance, even as reformers sought to dismantle machine influence.

A comparative analysis highlights the strategic advantages of party alignment. Independent machines, though they existed, lacked the institutional support and reach of their party-affiliated counterparts. By tying themselves to the Democratic or Republican Party, machines gained access to a broader network of power, from local ward bosses to state governors and even presidents. This alignment also allowed machines to frame their activities as part of a larger political movement, appealing to voters’ partisan identities. For example, Tammany Hall’s Democratic affiliation helped it portray itself as the champion of the common man against Republican elitism, a narrative that resonated with New York’s immigrant population.

In practice, understanding this alignment offers insights into the mechanics of urban politics. For historians, it underscores the importance of party structures in sustaining machine power. For modern observers, it serves as a reminder of how local and national politics are interconnected. While political machines have largely faded from the American landscape, their legacy endures in the urban party alignments that still shape elections today. By studying this alignment, we gain a clearer picture of how power operates in cities—and how it can be challenged or reformed.

Understanding the Role of a State Chairman in Political Parties

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political machines were primarily associated with the Democratic Party, particularly in urban areas like New York City, Chicago, and Boston.

Yes, the Republican Party also operated political machines, though they were less prominent than their Democratic counterparts, especially in the North and Midwest.

In the South, political machines were often tied to the Democratic Party, as it dominated the region during the "Solid South" era.

While rare, some third parties, like the Tammany Hall-affiliated groups, occasionally influenced local politics, but major political machines were largely controlled by the Democrats and Republicans.

Party affiliation determined the patronage system, voter base, and policy priorities of political machines, with each machine aligning its activities to benefit its associated party.