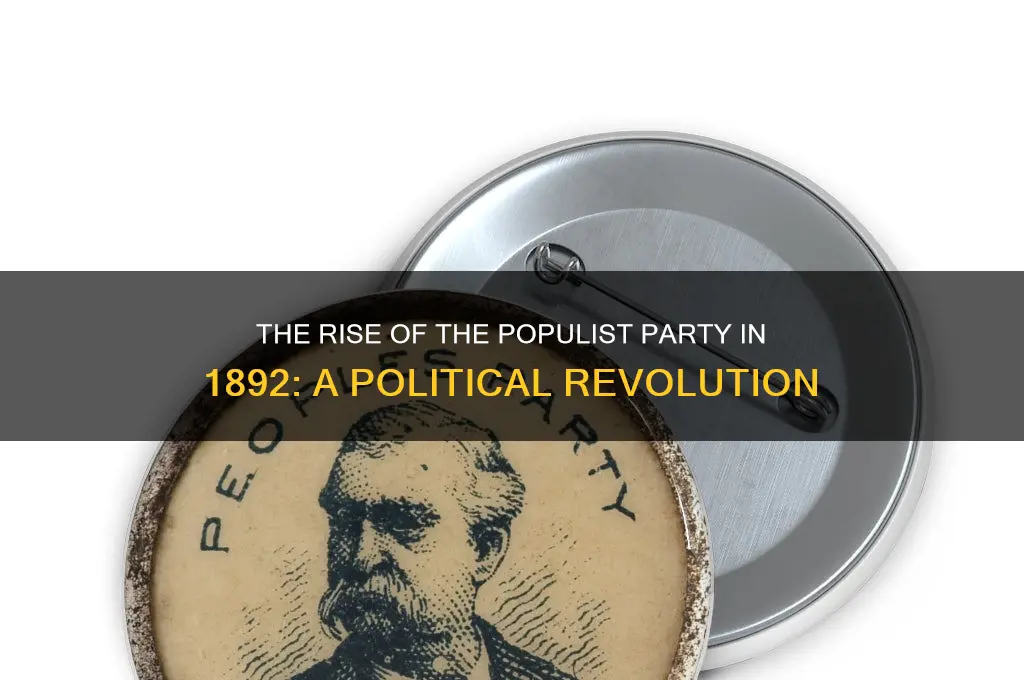

By 1892, the political landscape in the United States underwent a significant transformation with the formation of the Populist Party, officially known as the People's Party. Emerging as a response to the economic hardships faced by farmers and laborers during the late 19th century, the Populist Party advocated for radical reforms such as the nationalization of railroads, the abolition of national banks, and the implementation of a graduated income tax. Rooted in the agrarian discontent of the South and West, the party gained momentum through its Omaha Platform of 1892, which outlined its anti-monopolistic and pro-labor agenda. Led by figures like James B. Weaver, who ran as the party’s presidential candidate in 1892, the Populists sought to challenge the dominance of the Democratic and Republican parties, reflecting the growing divide between rural and urban interests in American society.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | People's Party (also known as the Populist Party) |

| Formation Year | 1891 (officially organized in 1892) |

| Founding Location | Omaha, Nebraska, USA |

| Ideology | Populism, Agrarianism, Anti-elitism, Economic reform |

| Key Goals | - Abolition of national banks - Government control of railroads - Direct election of senators - Graduated income tax - Free coinage of silver |

| Base of Support | Farmers, rural workers, and small-town residents in the Midwest and South |

| Prominent Figures | James B. Weaver, Ignatius L. Donnelly, Mary Elizabeth Lease |

| Election Success | James B. Weaver ran for president in 1892, winning 8.5% of the popular vote and 22 electoral votes |

| Decline | Merged with the Democratic Party after the 1896 election |

| Legacy | Influenced progressive reforms in the early 20th century |

| Symbol | Often associated with the "Omaha Platform" |

Explore related products

$7.01 $18

What You'll Learn

- Founding Members: Key figures who initiated the party's formation and their backgrounds

- Core Principles: Ideologies and policies that defined the party's mission and goals

- Historical Context: Political and social events that led to the party's creation

- First Election: Performance and impact in the initial electoral campaign of 1892

- Legacy: Long-term influence on politics and society beyond its founding year

Founding Members: Key figures who initiated the party's formation and their backgrounds

A search for political parties formed by 1892 reveals a notable example: the Populist Party, officially known as the People's Party, established in the United States. This party emerged as a response to the economic hardships faced by farmers and rural workers during the late 19th century. The founding members were a diverse group of individuals united by a common goal: to challenge the dominance of the Democratic and Republican parties and address the grievances of the agrarian population.

Key Figures and Their Backgrounds:

- Ignatius L. Donnelly (1831–1901): A prominent figure in the Populist movement, Donnelly was a former Republican congressman from Minnesota. His background in politics and his experience as a farmer gave him a unique perspective on the struggles of rural America. Donnelly's influential book, *Caesar's Column*, and his speeches at the 1892 Omaha Convention played a pivotal role in shaping the party's platform, which included demands for government control of railroads, a graduated income tax, and the direct election of senators.

- James B. Weaver (1833–1912): Weaver, a former Union Army officer and Greenback Party member, brought military discipline and a strong sense of justice to the Populist Party. Having served in Congress as a Democrat and later as a Greenbacker, he understood the intricacies of Washington politics. Weaver's presidential candidacy in 1892 under the Populist banner symbolized the party's rapid rise, attracting over a million votes and carrying five states. His background in law and military service added credibility to the party's leadership.

- Mary Elizabeth Lease (1850–1933): A fiery orator and women's rights advocate, Lease was one of the few women at the forefront of the Populist movement. Her background as a teacher and lawyer, coupled with her experience as a farm wife, gave her a powerful voice in articulating the struggles of rural families. Lease's speeches, often delivered to large crowds, emphasized the need for economic reform and women's suffrage, making her a pivotal figure in mobilizing grassroots support for the party.

- Tom Watson (1856–1922): A young and charismatic lawyer from Georgia, Watson became a leading voice for the Populist cause in the South. His background in journalism allowed him to effectively communicate the party's message through newspapers like *The People's Party Paper*. Watson's efforts to bridge the racial divide, advocating for the inclusion of African American farmers in the Populist movement, were groundbreaking, though ultimately fraught with challenges. His leadership helped expand the party's influence beyond the Midwest.

Analysis and Takeaway: The founding members of the Populist Party brought a unique blend of political experience, grassroots activism, and diverse backgrounds to the table. Their collective efforts not only challenged the status quo but also laid the groundwork for future progressive reforms in American politics. By understanding their individual contributions, we gain insight into the party's rapid rise and its enduring legacy in shaping modern political discourse.

Practical Tip: When studying political movements, focus on the biographies of key figures to understand the personal motivations and experiences that drive collective action. This approach provides a deeper, more nuanced understanding of historical events and their impact.

Haven Caravelli's Political Party: Vision, Impact, and Future Prospects

You may want to see also

Core Principles: Ideologies and policies that defined the party's mission and goals

The People's Party, commonly known as the Populists, emerged in 1892 as a response to the economic and political grievances of rural and agrarian Americans. Their core principles were rooted in a radical critique of the Gilded Age’s monopolistic practices and the failures of the two-party system. Central to their ideology was the belief that the government had been co-opted by wealthy industrialists, bankers, and railroad barons, leaving farmers and laborers exploited and powerless. This analysis underscores the Populists’ mission: to reclaim democracy for the common people and dismantle the concentration of wealth and power.

One of the defining policies of the People’s Party was the demand for a single, flexible currency system backed by both gold and silver. This "bimetallism" was not merely an economic proposal but a symbolic stand against the deflationary policies that had devastated farmers’ incomes. By advocating for free coinage of silver, the Populists aimed to increase the money supply, ease debt burdens, and stimulate rural economies. This policy reflected their broader commitment to economic justice and their understanding of currency as a tool for redistributing power from financiers to producers.

Another cornerstone of Populist ideology was the call for government ownership of railroads, telegraphs, and other essential industries. They argued that private monopolies had become predatory, charging exorbitant rates and stifling competition. Public control, they believed, would ensure fair prices and equitable access for farmers and small businesses. This policy was a direct challenge to the laissez-faire orthodoxy of the time and demonstrated the Populists’ willingness to rethink the role of government in the economy.

The Populists also championed political reforms to democratize the electoral process. They advocated for the direct election of senators, the implementation of the secret ballot, and the introduction of initiative and referendum systems. These measures were designed to reduce corruption, increase transparency, and give citizens a more direct say in governance. By targeting the structural flaws of the political system, the Populists sought to empower the electorate and curb the influence of special interests.

Finally, the People’s Party embraced a cooperative vision of society, promoting the idea that collective action could overcome individual vulnerability. They encouraged the formation of farmers’ cooperatives, labor unions, and mutual aid societies as alternatives to corporate dominance. This emphasis on solidarity and self-help reflected their belief in the dignity of labor and the potential for grassroots organizing to effect systemic change. While the Populists’ electoral success was short-lived, their core principles laid the groundwork for progressive reforms in the 20th century, from antitrust legislation to the welfare state.

Unveiling the Guardians: Who Really Owns the Politics Watchdog?

You may want to see also

Historical Context: Political and social events that led to the party's creation

The late 19th century was a period of profound economic and social upheaval in the United States, setting the stage for the formation of new political movements. By 1892, the Populist Party, officially known as the People's Party, emerged as a response to the growing discontent among farmers, laborers, and rural communities. This party’s creation was not an isolated event but the culmination of decades of political and social ferment. The Panic of 1873 and the subsequent Long Depression had devastated agricultural prices, leaving farmers burdened with debt and at the mercy of railroads, banks, and industrial monopolies. These economic pressures created a fertile ground for a political movement that would challenge the dominance of the two-party system and advocate for the rights of the common people.

One of the key catalysts for the Populist Party’s formation was the rise of the Farmers’ Alliance, a grassroots movement that organized millions of farmers across the South and Midwest. The Alliance initially focused on cooperative economic strategies, such as collective bargaining for better crop prices and lower transportation costs. However, as these efforts proved insufficient against entrenched corporate interests, the movement shifted toward political action. The Alliance’s demands, including the abolition of national banks, the implementation of a graduated income tax, and the nationalization of railroads, became central to the Populist Party’s platform. This transition from economic cooperation to political activism underscores the growing realization among farmers that systemic change required direct engagement with the political system.

Simultaneously, the labor movement was gaining momentum, fueled by the harsh conditions faced by industrial workers. Strikes, such as the Haymarket Affair in 1886 and the Homestead Strike in 1892, highlighted the tensions between workers and industrialists. While the Populist Party primarily represented agrarian interests, its platform resonated with urban laborers who shared similar grievances against monopolistic corporations and a corrupt political establishment. The party’s call for an eight-hour workday, the direct election of senators, and the public ownership of essential industries bridged the gap between rural and urban discontent, creating a broad coalition of reformers.

The political landscape of the 1890s was also shaped by the failures of the major parties to address the nation’s pressing issues. The Democratic and Republican parties were seen as captive to corporate interests, leaving little room for policies that would alleviate the suffering of ordinary Americans. The Populist Party’s emergence was, in part, a reaction to this political stagnation. By offering a radical alternative to the status quo, the party sought to democratize the political process and empower those who had been marginalized by the existing system. Its formation was a testament to the power of grassroots organizing and the enduring demand for economic justice in the face of inequality.

In conclusion, the creation of the Populist Party by 1892 was the result of a complex interplay of economic, social, and political forces. The struggles of farmers and laborers, coupled with the failures of the established parties, created a vacuum that the Populists sought to fill. While the party’s success was short-lived, its legacy endures as a reminder of the potential for ordinary people to challenge entrenched power structures and demand meaningful change. Understanding this historical context provides valuable insights into the conditions that give rise to new political movements and the enduring relevance of their ideals.

Finding Your Political Niche: A Guide to Understanding Your Beliefs

You may want to see also

Explore related products

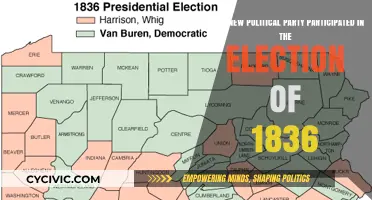

First Election: Performance and impact in the initial electoral campaign of 1892

The People's Party, commonly known as the Populists, emerged in 1892 as a response to the economic and political grievances of farmers and laborers in the late 19th century. Their first electoral campaign in 1892 was a bold experiment in challenging the dominance of the Democratic and Republican parties. With James B. Weaver as their presidential candidate, the Populists sought to address issues like monetary policy, land ownership, and corporate power. Their performance in this inaugural campaign was both a testament to their grassroots appeal and a reflection of the limitations they faced in a two-party system.

Analytically, the Populists’ 1892 campaign demonstrated the power of mobilizing marginalized groups. They secured over one million votes and carried five states, primarily in the West and South, where economic discontent was most acute. This success was unprecedented for a third party, signaling a shift in American politics. However, their inability to win more states highlighted the structural barriers third parties face, such as winner-take-all electoral systems and entrenched party loyalties. The Populists’ platform, which included the free coinage of silver and government control of railroads, resonated with farmers but failed to attract urban workers or industrial interests, limiting their national reach.

Instructively, the Populists’ campaign offers lessons for modern third-party movements. They built a coalition through local organizing, leveraging farmers’ alliances and labor unions to spread their message. Their use of rallies, pamphlets, and grassroots networks was a model of pre-modern political campaigning. Yet, their failure to secure broader alliances underscores the importance of inclusivity. Modern third parties can learn from the Populists’ focus on economic issues but must avoid alienating diverse voter groups. For instance, a contemporary third party might adopt the Populists’ strategy of targeting specific regions while broadening its appeal to include urban and suburban voters.

Persuasively, the impact of the Populists’ 1892 campaign extends beyond their immediate electoral gains. They forced the major parties to address issues like antitrust legislation and financial reform, shaping the Progressive Era that followed. Their ideas, such as the graduated income tax and direct election of senators, eventually became law. This legacy argues for the value of third parties in pushing the political system toward reform. While the Populists did not win the presidency, they demonstrated that a focused, issue-driven campaign can influence national discourse and policy, even in defeat.

Comparatively, the Populists’ first election performance contrasts with other third-party efforts, such as Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party in 1912. While Roosevelt’s campaign was more successful in terms of votes, the Populists achieved greater regional penetration and policy influence. The Populists’ ability to win entire states, despite their limited resources, highlights the effectiveness of their grassroots approach. In contrast, Roosevelt’s campaign relied more on personal charisma and existing political networks. This comparison suggests that third-party success depends on both organizational strategy and the ability to tap into widespread discontent.

Descriptively, the 1892 campaign was a vivid display of American democracy in action. Populist rallies were electric, with speakers denouncing monopolies and calling for economic justice. Their campaign literature, often printed on cheap paper, circulated widely in rural areas, reaching voters who felt ignored by the major parties. The Populists’ use of symbols like the “Omaha Platform” and their focus on tangible issues like debt relief created a sense of urgency and purpose. This ground-level energy, though insufficient to win the presidency, left an indelible mark on American politics, proving that even a first-time party could challenge the status quo.

Vietnam's Post-Independence Political Shift: The Rise of a New Party

You may want to see also

Legacy: Long-term influence on politics and society beyond its founding year

The People's Party, also known as the Populist Party, emerged in 1892 as a response to the economic and social struggles faced by farmers and rural workers in the late 19th-century United States. While the party's direct political influence waned after the turn of the century, its legacy extends far beyond its founding year, shaping long-term political and societal trends in profound ways. One of its most enduring contributions was the introduction of progressive ideas that later became mainstream, such as the direct election of senators, the implementation of a graduated income tax, and the establishment of a federal reserve system. These reforms, initially radical, laid the groundwork for the Progressive Era and continue to influence modern governance.

Consider the party's platform as a blueprint for addressing economic inequality. The Populists advocated for policies like the nationalization of railroads and the abolition of national banks, which, while not fully realized at the time, foreshadowed later government interventions in industries deemed essential to public welfare. For instance, the New Deal of the 1930s echoed Populist demands for federal regulation of corporations and financial institutions. Today, debates over antitrust laws and corporate accountability often trace their roots back to these early Populist ideas. To apply this historically: examine how modern movements like Occupy Wall Street or calls for a "Green New Deal" repurpose Populist themes of economic fairness and government responsibility.

A comparative analysis reveals the Populist Party's influence on labor rights and social justice movements. Their support for the eight-hour workday and opposition to child labor set precedents for labor laws enacted in the 20th century. Similarly, their inclusion of women and African Americans in leadership roles, though limited, challenged the era's norms and inspired future civil rights activism. For practical engagement, educators and activists can trace the lineage of these demands through historical documents like the Omaha Platform of 1892, connecting them to contemporary issues such as the Fight for $15 or voting rights reforms.

Persuasively, the Populist Party's legacy also serves as a cautionary tale about the challenges of sustaining third-party movements. Despite their innovative ideas, internal divisions and co-optation by major parties ultimately limited their longevity. However, their ability to shift the Overton window—the range of policies considered politically acceptable—demonstrates the power of grassroots organizing. For those building modern political movements, the takeaway is clear: focus on policy-driven coalitions rather than personality-centered campaigns. By anchoring demands in tangible, broadly appealing reforms, as the Populists did, movements can leave a lasting impact even if they do not achieve immediate electoral success.

Descriptively, the Populist Party's cultural imprint is evident in literature, art, and folklore. Figures like Mary Elizabeth Lease, who famously urged farmers to "raise less corn and more hell," became symbols of resistance against entrenched power. Their rhetoric and imagery—depictions of farmers battling monopolistic "octopuses"—resonate in today’s populist discourse, both on the left and right. To explore this, analyze how contemporary political cartoons or memes repurpose these motifs. Understanding this cultural legacy helps explain why populist sentiments, though often amorphous, remain a recurring feature of political landscapes worldwide.

Why Italian Politics Are So Complex and Chaotic

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Populist Party, officially known as the People's Party, was formed by 1892.

Key figures included farmers' advocates like Ignatius Donnelly, James Weaver, and leaders from the Farmers' Alliance movement.

The Populist Party aimed to address economic grievances of farmers, advocating for policies like the free coinage of silver, government control of railroads, and a graduated income tax.

The Populist Party candidate, James B. Weaver, received over 1 million votes and won several Western states, though he did not win the presidency.