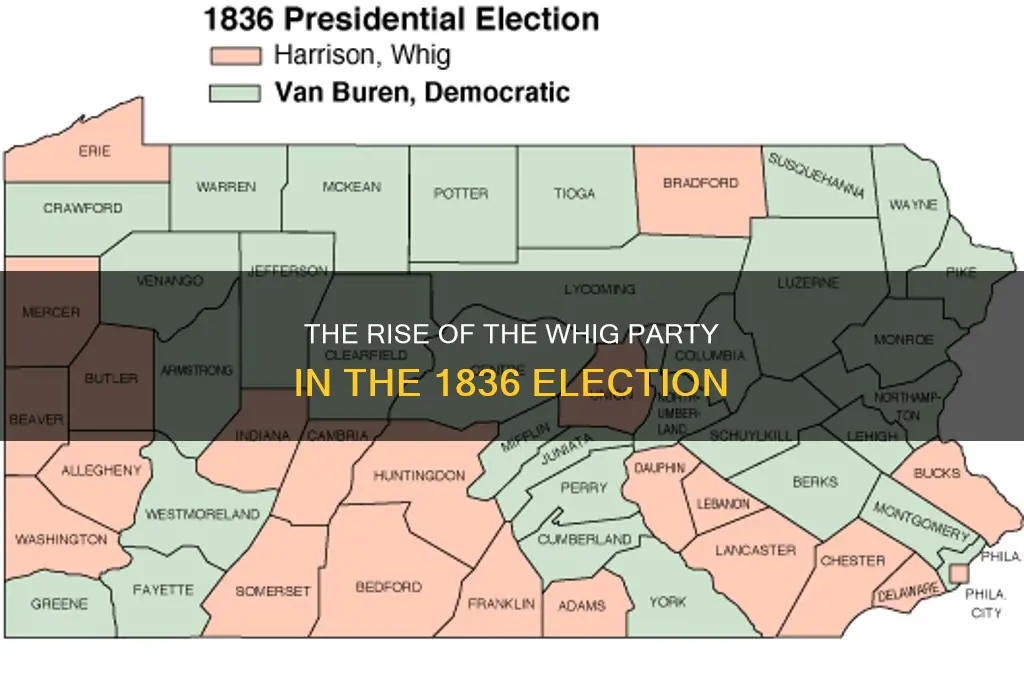

The election of 1836 marked a significant shift in American politics with the emergence of the Whig Party as a major contender. Formed in opposition to President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic Party, the Whigs coalesced around a platform that emphasized economic modernization, internal improvements, and a stronger federal role in fostering national development. Led by figures like Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, the Whigs sought to challenge Jacksonian democracy, which they viewed as overly populist and threatening to constitutional checks and balances. In the 1836 election, the Whigs, still a loosely organized coalition, fielded multiple regional candidates under the Whig banner, aiming to prevent Jackson’s chosen successor, Martin Van Buren, from securing a majority in the Electoral College. Though Van Buren ultimately won, the Whigs' participation signaled the rise of a new political force that would shape American politics for decades to come.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Whig Party |

| Year Founded | 1833-1834 |

| First Presidential Election Participation | 1836 |

| Key Figures | Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, John Quincy Adams |

| Ideology | National bank, internal improvements, opposition to Andrew Jackson's policies |

| Platform | Strong federal government, economic modernization, protection of liberties |

| Candidate in 1836 Election | Multiple regional candidates (William Henry Harrison, Hugh Lawson White, Daniel Webster) |

| Election Outcome | Martin Van Buren (Democrat) won; Whigs failed to unite behind a single candidate |

| Longevity | Active until the 1850s, when it dissolved due to internal divisions over slavery |

| Legacy | Laid groundwork for the Republican Party; influenced American political thought |

Explore related products

$34.77 $37.99

$37.99 $37.99

What You'll Learn

Martin Van Buren's Democratic Party

The 1836 presidential election marked a pivotal moment in American political history, as it introduced a new political landscape dominated by the Democratic Party, led by Martin Van Buren. This election was unique because it featured the emergence of the Whig Party as a major contender, but it was Van Buren’s Democratic Party that solidified its position as a dominant force. Van Buren’s victory was not just a personal triumph but a testament to the organizational prowess and ideological coherence of the Democratic Party, which had evolved from the Democratic-Republican Party of the early 19th century.

To understand Van Buren’s Democratic Party, consider its strategic focus on unifying diverse interests under a single banner. Unlike the Whigs, who were a coalition of disparate groups opposing Andrew Jackson’s policies, the Democrats presented a clear platform centered on states’ rights, limited federal government, and the expansion of democracy. Van Buren, often called the "Little Magician," was a master organizer who built a robust party machine. This machine relied on local and state-level networks, ensuring grassroots support and disciplined voter turnout. For instance, the party’s use of patronage—appointing loyalists to government positions—strengthened its hold on power and rewarded supporters, a tactic that became a hallmark of 19th-century American politics.

A comparative analysis reveals how Van Buren’s Democrats differentiated themselves from their predecessors and rivals. While the Democratic-Republican Party of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison emphasized agrarian interests and strict construction of the Constitution, Van Buren’s Democrats adapted to the changing economic and social landscape of the 1830s. They embraced the rise of urbanization and industrialization, albeit cautiously, while maintaining their commitment to states’ rights. This adaptability allowed them to appeal to a broader electorate, including farmers, workers, and emerging urban elites. In contrast, the Whigs struggled to present a unified vision, often appearing as a party of opposition rather than innovation.

Persuasively, Van Buren’s leadership and the Democratic Party’s success in 1836 highlight the importance of political organization and ideological clarity in winning elections. Van Buren’s ability to navigate complex political terrain, from the Bank War to the issue of slavery, demonstrated his skill as a pragmatic leader. His party’s platform, while not without contradictions, offered a coherent vision that resonated with voters. For modern political organizers, the lesson is clear: building a strong party infrastructure and articulating a compelling narrative are essential for electoral success. Practical tips include investing in local leadership, leveraging technology for outreach (akin to Van Buren’s use of newspapers), and fostering coalitions that bridge diverse interests.

Descriptively, the 1836 election showcased the Democrats’ innovative campaign tactics. Van Buren’s team employed rallies, parades, and printed materials to mobilize voters, creating a sense of excitement and loyalty. The party’s use of symbols, such as the Democratic rooster, and slogans like "Hurrah for Van, the Man of the People!" tapped into the emotional and cultural currents of the time. These methods, while rudimentary by today’s standards, were groundbreaking in their era and set a precedent for modern campaign strategies. For anyone studying political history or organizing campaigns, examining these tactics provides valuable insights into the evolution of electoral engagement.

In conclusion, Martin Van Buren’s Democratic Party was not just a participant in the 1836 election but a transformative force that reshaped American politics. Its success lay in its ability to combine organizational strength, ideological adaptability, and strategic communication. By studying Van Buren’s approach, we gain a deeper understanding of how political parties can rise to dominance and sustain their influence. This historical example remains relevant, offering timeless lessons in leadership, strategy, and the art of winning elections.

Origins of Political Party Splits: Unraveling the First Division's Catalysts

You may want to see also

Whig Party's Emergence

The 1836 U.S. presidential election marked a pivotal moment in American political history with the emergence of the Whig Party, a new force challenging the dominance of Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party. Born out of opposition to Jackson’s expansive executive power and policies like the Indian Removal Act and the dismantling of the Second Bank of the United States, the Whigs coalesced from a diverse coalition of National Republicans, Anti-Masons, and disaffected Democrats. Their platform emphasized legislative authority, economic modernization through internal improvements, and a rejection of what they saw as Jackson’s "tyranny of the majority."

1836 was unique: the Whigs, still organizing regionally, did not field a single presidential candidate but instead nominated multiple contenders—William Henry Harrison, Hugh Lawson White, Daniel Webster, and Willie Person Mangum—to compete in different regions. This strategy aimed to deny Jackson’s chosen successor, Martin Van Buren, an electoral majority, throwing the election to the House of Representatives where deals could be brokered. Though Van Buren won, the Whigs’ tactical innovation and their 70+ electoral votes signaled their arrival as a major party.

The Whigs’ emergence reflected broader societal shifts. The Industrial Revolution was transforming the economy, and Whigs championed government-supported infrastructure (canals, roads, railroads) to accelerate growth. They appealed to entrepreneurs, urban workers, and those wary of Jackson’s agrarian populism. Their organizational structure, built on local committees and mass rallies, pioneered modern campaign techniques. For instance, Harrison’s 1840 "Log Cabin Campaign" used symbolism (hard cider, log cabins) to connect with voters, a tactic still studied in political marketing.

However, the Whigs’ 1836 strategy had limitations. Their multi-candidate approach, while innovative, lacked national cohesion. Regional nominees struggled to articulate a unified vision, and the party’s reliance on anti-Jackson sentiment rather than positive policy proposals left ideological gaps. This weakness became evident in 1836 when Van Buren secured victory despite Whig efforts. Yet, the election laid groundwork for Harrison’s 1840 triumph, proving the Whigs’ ability to adapt and mobilize.

The Whigs’ emergence offers lessons for modern third-party movements. Their success stemmed from identifying a clear adversary (Jackson), harnessing economic anxieties, and leveraging organizational innovation. However, their 1836 experience highlights the risks of fragmentation and the need for a coherent national message. Aspiring parties today might emulate the Whigs’ grassroots energy while avoiding their ideological ambiguity, ensuring a platform resonates across diverse constituencies.

Nazis' Political Spectrum: Unraveling Their Extreme Right-Wing Ideology

You may want to see also

Anti-Masonic Influence

The 1836 U.S. presidential election marked a pivotal moment in American political history, not only for the candidates but also for the emergence of new political forces. Among these, the Anti-Masonic Party stands out as a unique and influential player. This party, though short-lived, left a lasting impact on the political landscape, particularly in its opposition to the perceived secrecy and influence of Freemasonry in government.

The Rise of Anti-Masonic Sentiment

In the early 1830s, a wave of anti-Masonic sentiment swept through the United States, fueled by the mysterious disappearance of William Morgan, a former Freemason who had threatened to expose the organization’s secrets. Morgan’s presumed murder in 1826 ignited public outrage, leading to the formation of the Anti-Masonic Party in 1828. By 1836, the party had gained enough traction to field its own presidential candidate, William Wirt, a former Attorney General. While Wirt’s campaign did not secure the presidency, the party’s influence was evident in its ability to shape public discourse and challenge the dominance of the Democratic and Whig parties.

Strategic Focus and Electoral Impact

The Anti-Masonic Party’s platform was narrow but potent, centered on the belief that Freemasons were conspiring to control government and undermine democracy. This focus allowed the party to appeal to voters who felt alienated by the established political elite. In the 1836 election, the party’s strongest showing was in Vermont, where it won the state’s electoral votes. This success demonstrated the power of single-issue politics and the ability of a new party to disrupt traditional electoral dynamics. However, the party’s limited scope also hindered its long-term viability, as it struggled to expand its platform beyond anti-Masonry.

Legacy and Broader Implications

Though the Anti-Masonic Party dissolved by the mid-1840s, its influence persisted. It paved the way for future third parties by proving that a focused, grassroots movement could challenge the two-party system. Additionally, the party’s emphasis on transparency and accountability resonated with broader reform movements, such as temperance and abolitionism. The 1836 election thus serves as a case study in how a new political party, driven by a specific cause, can shape national conversations and leave a lasting legacy, even if it fails to win the ultimate prize.

Practical Takeaways for Modern Politics

For modern political organizers, the Anti-Masonic Party offers valuable lessons. First, single-issue campaigns can galvanize support, but they must evolve to address a broader range of concerns to sustain momentum. Second, leveraging public outrage over specific issues, as the party did with the Morgan affair, can be a powerful mobilizing tool. Finally, while third parties often face significant barriers, their impact on mainstream politics can be profound, pushing established parties to address neglected issues. The Anti-Masonic Party’s role in the 1836 election underscores the importance of innovation and persistence in challenging the status quo.

From Factions to Polarization: Tracing the Evolution of US Political Parties

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Southern Rights Candidates

The 1836 presidential election was a pivotal moment in American political history, marked by the emergence of new parties and factions. Among these, the Southern Rights Candidates stood out as a distinct group advocating for states' rights and sectional interests. This movement, though not a formal party, represented a coalition of politicians primarily from the South who sought to protect their region's economic and social structures, particularly slavery, against perceived Northern encroachment.

To understand the Southern Rights Candidates, consider their strategic alignment with the Whig Party in certain states. In Alabama, for instance, they endorsed Whig candidate Hugh Lawson White, while in Mississippi, they supported Democrat Richard M. Johnson. This tactical flexibility highlights their primary goal: to ensure Southern representation and influence regardless of the national party dynamics. Their platform was less about winning the presidency and more about safeguarding regional autonomy, a theme that would intensify in the decades leading up to the Civil War.

Analyzing their impact, the Southern Rights Candidates foreshadowed the rise of the Southern Democratic Party and later the Confederate movement. Their focus on states' rights and resistance to federal authority laid the groundwork for future secessionist ideologies. While they did not achieve a unified national presence in 1836, their efforts underscored the growing divide between North and South, setting the stage for more polarized political landscapes.

For those studying political movements, the Southern Rights Candidates offer a case study in regionalism and its influence on national politics. Their approach demonstrates how localized interests can shape broader electoral strategies. To replicate their tactical alignment, modern political groups might consider forming issue-based coalitions rather than rigid party structures. However, caution is advised: such movements can exacerbate sectional tensions, as evidenced by the eventual fragmentation of the Union.

In practical terms, understanding the Southern Rights Candidates requires examining primary sources like campaign pamphlets and legislative records from the 1830s. These documents reveal the nuanced arguments they used to rally support, blending economic concerns with cultural identity. For educators or researchers, incorporating these materials into curricula or analyses can provide a richer understanding of antebellum politics. Ultimately, the Southern Rights Candidates remind us that regional interests often drive national narratives, a lesson as relevant today as it was in 1836.

John Boehner's Political Party Affiliation: A Comprehensive Overview

You may want to see also

William Henry Harrison's Role

The 1836 U.S. presidential election marked a pivotal moment in American political history, as it introduced the Whig Party as a major contender. Among the Whigs' key figures was William Henry Harrison, whose role was both strategic and symbolic. Harrison's candidacy was a calculated move by the Whigs to challenge the dominant Democratic Party, led by incumbent President Andrew Jackson and his chosen successor, Martin Van Buren. Harrison's military background, particularly his victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe, became a central theme in his campaign, earning him the nickname "Old Tippecanoe." This image of a war hero resonated with voters, positioning Harrison as a strong leader in contrast to the more politically seasoned Van Buren.

Analyzing Harrison's role reveals the Whigs' tactical use of his persona to unify their diverse coalition. The Whig Party, formed in opposition to Jacksonian democracy, lacked a cohesive ideology but found common ground in their opposition to executive overreach. Harrison's appeal lay in his ability to transcend regional and factional divides. His military fame in the Northwest appealed to Western voters, while his modest upbringing and frontier credentials resonated with Southern and Eastern constituents. By nominating Harrison, the Whigs aimed to create a broad-based movement that could rival the Democrats' populist appeal.

However, Harrison's role was not without challenges. The 1836 election was unusual in that the Whigs ran multiple regional candidates to maximize their electoral votes, with Harrison as the primary contender in the North and West. This strategy, while innovative, diluted the party's message and highlighted internal divisions. Harrison's own campaign was marked by a lack of clear policy positions, as the Whigs focused instead on his character and reputation. This approach, while effective in rallying support, left voters uncertain about his vision for the nation.

Despite these limitations, Harrison's role in the 1836 election laid the groundwork for his eventual victory in 1840. His campaign introduced themes of log cabins and hard cider, which became iconic in American political folklore. These symbols, though simplistic, effectively portrayed Harrison as a man of the people, in stark contrast to the elitist image the Whigs sought to attach to Van Buren. Harrison's 1836 campaign, though unsuccessful, was a critical stepping stone in the Whigs' rise to power and demonstrated the enduring power of personal branding in politics.

In conclusion, William Henry Harrison's role in the 1836 election was instrumental in shaping the Whig Party's identity and strategy. His candidacy exemplified the Whigs' ability to leverage symbolism and personality to challenge Democratic dominance. While the election itself was a defeat for Harrison, it set the stage for his later triumph and underscored the importance of narrative in political campaigns. Harrison's legacy in 1836 reminds us that in politics, the story often matters as much as the substance.

Immigrant-Centric Politics: Exploring the Party Championing New Americans' Rights

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Whig Party was the new political party that participated in the election of 1836.

The Whig Party emerged as a coalition of opponents to President Andrew Jackson and his Democratic Party, uniting around concerns over Jackson's policies and executive power.

The Whig Party did not run a single candidate in 1836 but instead fielded multiple regional candidates, including William Henry Harrison, Hugh Lawson White, Daniel Webster, and Willie Person Mangum.

No, the Whig Party did not win the 1836 presidential election. Democrat Martin Van Buren defeated the Whigs and became president.

The Whig Party's platform in 1836 emphasized opposition to Andrew Jackson's policies, support for a national bank, internal improvements, and a stronger role for Congress in governance.