In 1912, former President Theodore Roosevelt, dissatisfied with the policies of his successor, William Howard Taft, and the Republican Party, decided to challenge Taft for the Republican nomination. After losing the nomination, Roosevelt and his progressive supporters broke away from the Republican Party and formed a new political party. Roosevelt named this new party the Progressive Party, often referred to as the Bull Moose Party due to his famous declaration that he felt as strong as a bull moose. The party championed progressive reforms, including trust-busting, labor rights, and social welfare programs, reflecting Roosevelt's vision for a more equitable and responsive government.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Progressive Party Formation

Theodore Roosevelt's decision to name his new political party the Progressive Party in 1912 was a strategic move rooted in the era's reformist zeitgeist. The term "Progressive" itself was a rallying cry for those seeking to address the social, economic, and political inequalities exacerbated by the Gilded Age. By adopting this name, Roosevelt aimed to distinguish his party from the entrenched interests of the Republican and Democratic establishments, positioning it as a vehicle for change. The label resonated with a broad coalition of reformers, including labor advocates, women suffragists, and anti-corruption crusaders, who saw progressivism as a unifying banner for their diverse causes.

The formation of the Progressive Party, often referred to as the "Bull Moose Party," was a direct response to Roosevelt's disillusionment with the Republican Party under President William Howard Taft. After Taft abandoned Roosevelt's progressive agenda, Roosevelt sought the Republican nomination in 1912 but was denied. Undeterred, he and his supporters convened in Chicago to establish a new party, embodying the principles of social justice, government reform, and economic fairness. This bold move was not just about winning an election but about redefining American politics by prioritizing the public good over partisan interests.

To understand the Progressive Party's formation, consider its platform as a blueprint for reform. Key planks included antitrust legislation, women's suffrage, workers' rights, and conservation efforts—issues that mainstream parties had largely ignored. Roosevelt's ability to coalesce these disparate reform movements under a single banner was a testament to his political acumen and the era's appetite for change. The party's formation was a high-stakes gamble, but it forced both major parties to address progressive ideas, leaving a lasting impact on American political discourse.

Practical lessons from the Progressive Party's formation include the importance of branding in political movements. The name "Progressive" was more than a label; it was a statement of purpose that attracted a wide audience. Modern political organizers can emulate this by choosing names and messaging that clearly articulate their values and goals. Additionally, Roosevelt's willingness to break from his own party underscores the necessity of prioritizing principles over loyalty when the stakes are high. For activists today, this serves as a reminder that systemic change often requires bold, unconventional actions.

In conclusion, the Progressive Party's formation was a pivotal moment in American political history, demonstrating how a well-named and principled movement can challenge the status quo. Roosevelt's choice of the name "Progressive" was not arbitrary but a deliberate strategy to align his party with the era's most pressing reforms. By studying this episode, we gain insights into the power of political branding, the importance of coalition-building, and the enduring relevance of progressive ideals in shaping public policy.

Foreign Funding for Political Parties: Legal, Ethical, or Risky?

You may want to see also

Bull Moose Nickname Origin

The Progressive Party, founded by Theodore Roosevelt in 1912, is often remembered not by its formal name but by its iconic nickname: the Bull Moose Party. This moniker originated from Roosevelt’s own declaration during his campaign, when he proclaimed, “I’m as strong as a bull moose.” The phrase was more than a boast; it was a strategic rebranding that captured the party’s vigor and Roosevelt’s unyielding determination to challenge the established political order. By embracing the nickname, Roosevelt transformed a simple animal reference into a symbol of resilience and reform, aligning perfectly with his progressive agenda.

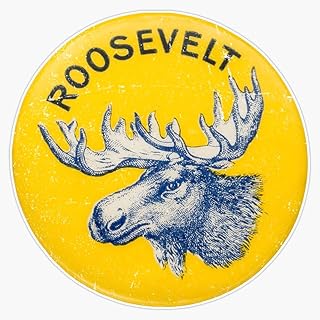

To understand the nickname’s impact, consider its context. Roosevelt’s split from the Republican Party, led by incumbent President William Howard Taft, was dramatic and contentious. The Bull Moose nickname served as a rallying cry for his supporters, distinguishing them from the traditional Republicans and Democrats. It was a masterclass in political branding, turning a personal assertion into a collective identity. For instance, campaign materials often featured bull moose imagery, and supporters proudly adopted the name, wearing buttons and hats emblazoned with the animal. This visual and verbal branding made the party instantly recognizable, even to those unfamiliar with its platform.

Analytically, the Bull Moose nickname highlights Roosevelt’s skill in leveraging symbolism to convey his message. The moose, a creature known for its strength and endurance, mirrored Roosevelt’s own persona and the party’s commitment to progressive reforms. This alignment between symbol and substance was no accident. Roosevelt understood that in politics, perception often shapes reality. By associating his party with the bull moose, he not only created a memorable identity but also subtly communicated the party’s core values: robustness, tenacity, and a willingness to fight for change.

Practical takeaways from this origin story are clear. For modern political movements or brands seeking to create a lasting impression, the Bull Moose example underscores the power of a well-chosen symbol. It’s not enough to have a strong message; the message must be encapsulated in a form that resonates emotionally and visually. Whether through a catchy phrase, a distinctive logo, or a compelling mascot, the goal is to create an identity that sticks. Roosevelt’s Bull Moose nickname demonstrates how a single, bold statement can become the cornerstone of a movement’s identity.

Finally, the Bull Moose nickname serves as a reminder of the enduring impact of personal leadership in shaping political narratives. Roosevelt’s charisma and willingness to embrace the moniker turned it into more than just a nickname—it became a movement. This lesson is particularly relevant today, where leaders often struggle to balance authenticity with strategic messaging. By embodying the spirit of the bull moose, Roosevelt showed that authenticity and strategy can coexist, creating a legacy that continues to inspire.

Why Political Leaders Are Essential for Society's Progress and Stability

You may want to see also

1912 Election Campaign

The 1912 presidential election stands as a pivotal moment in American political history, marked by the dramatic split within the Republican Party and the rise of a third-party challenger. Theodore Roosevelt, the former president and a towering figure in American politics, had grown disillusioned with his successor, William Howard Taft, over issues like trust-busting and conservation. This ideological rift led Roosevelt to mount an unprecedented challenge, forming a new political party to reclaim the presidency. The name he chose for this venture was the Progressive Party, but it quickly became known by a more evocative moniker: the Bull Moose Party. This name originated from Roosevelt’s declaration that he felt "as strong as a bull moose" after surviving an assassination attempt during the campaign, a phrase that captured the party’s tenacity and Roosevelt’s indomitable spirit.

Analytically, the 1912 campaign was a clash of ideologies and personalities. Roosevelt’s Progressive Party platform was bold and forward-thinking, advocating for social justice, labor rights, women’s suffrage, and government regulation of corporations. This contrasted sharply with Taft’s conservative Republican stance and the Democratic nominee, Woodrow Wilson, who offered a more moderate reform agenda. The campaign was not just about winning the presidency but about redefining the role of government in American society. Roosevelt’s Progressive Party, with its Bull Moose emblem, became a symbol of grassroots activism and reform, appealing to voters who felt alienated by the established parties. However, the party’s success was limited by the fragmented nature of the electorate and the spoiler effect it had on the Republican vote.

Instructively, the 1912 campaign offers valuable lessons for modern political strategists. Roosevelt’s decision to form a third party was a high-risk, high-reward move. While it allowed him to champion progressive ideals without compromise, it also divided the Republican vote, ensuring Wilson’s victory. For contemporary politicians considering a similar path, the takeaway is clear: third-party campaigns can amplify specific issues but often struggle to translate enthusiasm into electoral success. Roosevelt’s ability to galvanize supporters through charismatic leadership and a compelling platform remains a masterclass in political mobilization, but it underscores the challenges of breaking through the two-party system.

Persuasively, the Bull Moose Party’s legacy endures in the progressive reforms it championed. Roosevelt’s campaign pushed issues like workers’ rights, antitrust legislation, and environmental conservation into the national spotlight, forcing both major parties to address them. Wilson’s subsequent adoption of many progressive policies, such as the Federal Reserve Act and the Clayton Antitrust Act, can be traced back to the pressure Roosevelt applied in 1912. The Bull Moose Party may not have won the election, but it won the ideological battle, shaping the course of American politics for decades. Its story serves as a reminder that even unsuccessful campaigns can leave a lasting impact if they articulate a vision that resonates with the public.

Comparatively, the 1912 election stands out as one of the most unique in U.S. history due to the presence of three strong candidates. Roosevelt’s Bull Moose Party forced voters to choose between distinct visions for the nation’s future, unlike most elections, which often feature more incremental differences. This dynamic highlights the importance of clear, differentiated platforms in engaging the electorate. While third-party candidates today often struggle to gain traction, Roosevelt’s example shows that a charismatic leader with a compelling message can temporarily disrupt the political status quo. However, the election also underscores the structural barriers third parties face, a reality that continues to shape American politics.

Descriptively, the 1912 campaign was a spectacle of energy and innovation. Roosevelt’s rallies were electric, drawing massive crowds eager to hear his calls for a "New Nationalism." His survival of an assassination attempt, where a bullet lodged in his chest, only added to his mythos, reinforcing the Bull Moose Party’s image of resilience. Meanwhile, the party’s platform was a blueprint for progressive change, addressing issues from child labor to corporate greed. Though the campaign ended in defeat, it left an indelible mark on the nation’s political landscape, proving that sometimes, the fight itself is more significant than the outcome. The Bull Moose Party remains a testament to the power of conviction and the enduring appeal of bold ideas.

Exploring the Core Functions of Political Parties: Roles and Responsibilities

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Roosevelt’s Platform Goals

Theodore Roosevelt, after his split with the Republican Party, formed the Progressive Party, often referred to as the "Bull Moose Party." This name emerged from Roosevelt's declaration that he felt "as strong as a bull moose" during his campaign. The party's platform was a bold departure from traditional politics, focusing on reforms that prioritized the welfare of the average American over corporate interests. Roosevelt's goals were not just policy changes but a call to redefine the relationship between the government and its citizens.

One of the cornerstone goals of Roosevelt's platform was trust-busting and corporate regulation. He aimed to dismantle monopolies that stifled competition and exploited consumers. For instance, he proposed stricter oversight of railroads and utilities, ensuring fair pricing and preventing predatory practices. This approach wasn't just about economic fairness; it was about restoring power to the people by breaking the stranglehold of corporate giants. Small business owners and consumers alike could benefit from a more level playing field, fostering innovation and competition.

Another critical aspect of Roosevelt's agenda was social welfare and labor rights. He advocated for a minimum wage, an eight-hour workday, and safer working conditions, particularly for women and children. These reforms were revolutionary for the time, addressing the harsh realities of industrial labor. For families struggling to make ends meet, such policies promised a lifeline, ensuring that work was not just a means of survival but a pathway to dignity and stability.

Roosevelt also championed conservation and environmental stewardship, a cause close to his heart. He sought to protect natural resources from unchecked exploitation, proposing the creation of national parks and forests. This wasn't merely about preserving beauty; it was about ensuring sustainable use of resources for future generations. Farmers, hunters, and outdoor enthusiasts could all benefit from a balanced approach that respected both human needs and ecological limits.

Lastly, Roosevelt's platform emphasized direct democracy and political reform. He supported initiatives like the recall of judges, direct election of senators, and the use of referendums to bypass legislative gridlock. These measures aimed to give citizens a more direct say in governance, reducing the influence of special interests. For voters frustrated with political inertia, this was a refreshing call to action, empowering them to shape policies that directly impacted their lives.

In essence, Roosevelt's Progressive Party platform was a comprehensive blueprint for a more equitable and responsive government. By addressing economic, social, environmental, and political issues, he sought to create a nation where opportunity was not just a promise but a reality for all. His goals remain relevant today, serving as a reminder of the transformative power of bold, principled leadership.

Spain's Political System: Unraveling Its Unique Democratic Classification

You may want to see also

Impact on Republican Party

Theodore Roosevelt's decision to form the Progressive Party, colloquially known as the "Bull Moose Party," in 1912 sent shockwaves through the Republican Party. The immediate impact was a split in the GOP vote, as Roosevelt, a former Republican president, drew significant support from moderate and progressive Republicans. This division allowed Democrat Woodrow Wilson to win the presidency with just 41.8% of the popular vote, a clear demonstration of how Roosevelt's new party disrupted the traditional two-party dynamic. The Republican candidate, William Howard Taft, who had been Roosevelt's handpicked successor, secured only 23.2%, a humiliating defeat that underscored the depth of the party's fracture.

Analyzing the long-term consequences reveals a Republican Party forced to confront its ideological identity. Roosevelt's Progressive Party championed reforms like trust-busting, women's suffrage, and labor rights—issues that had been marginalized within the GOP. This compelled Republicans to either embrace these progressive ideas or double down on conservatism. The party ultimately chose the latter, shifting further rightward to distinguish itself from Roosevelt's platform. This ideological realignment alienated moderate Republicans, many of whom either left the party or became politically dormant, further narrowing the GOP's appeal.

From a strategic perspective, the Progressive Party's emergence highlighted the dangers of internal dissent for established political organizations. Roosevelt's break from the Republicans demonstrated that charismatic leaders could siphon off substantial support, particularly when they tapped into widespread public dissatisfaction. For the GOP, this meant reevaluating its candidate selection process and policy priorities to prevent future defections. However, the party's failure to adapt quickly enough left it vulnerable to further challenges, both from within and outside its ranks.

A comparative analysis with other third-party movements underscores the unique threat Roosevelt posed. Unlike most third parties, which fade into obscurity after an election, the Progressive Party's impact lingered, reshaping the Republican Party's trajectory for decades. While the party disbanded after 1916, its ideas persisted, influencing future GOP moderates and even Democrats. This contrasts sharply with movements like Ross Perot's Reform Party, which, despite initial fanfare, left minimal lasting impact on either major party.

Practically speaking, the Republican Party's response to Roosevelt's defection offers a cautionary tale for modern political organizations. To mitigate similar risks, parties must prioritize internal cohesion and address ideological divides before they escalate. This includes fostering open dialogue, incorporating diverse viewpoints into policy platforms, and selecting leaders who can unite rather than polarize. For Republicans today, the 1912 schism serves as a reminder that ignoring progressive or moderate factions can lead to fragmentation and electoral defeat. By studying this historical example, parties can develop strategies to navigate internal conflicts without sacrificing their core principles or voter base.

Are Local Political Parties Nonprofits? Exploring Their Legal Status

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Roosevelt named his new political party the Progressive Party, often referred to as the "Bull Moose Party."

Roosevelt formed the Progressive Party after a split with the Republican Party, as he sought to promote progressive reforms and challenge the conservative leadership of the GOP.

Roosevelt created the Progressive Party in 1912, following his unsuccessful bid to regain the Republican nomination for president.

The Progressive Party was nicknamed the "Bull Moose Party" after Roosevelt declared during his campaign, "I’m as strong as a bull moose," following his survival of an assassination attempt.

![Theodore Roosevelt'S Confession of Faith before the Progressive National Convention, August 6, 1912. 1912 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)