Understanding the percentage of each political party in a given region or country is crucial for analyzing political landscapes and predicting election outcomes. These percentages reflect the distribution of voter support among parties, often derived from election results, opinion polls, or membership data. In democratic systems, this information highlights the relative strength and influence of each party, shaping legislative power, policy-making, and governance. Factors such as demographic trends, economic conditions, and societal issues can significantly impact these percentages over time. Accurate data on party percentages also aids in identifying shifts in public sentiment, emerging political movements, and the potential for coalition-building. Whether examining national, regional, or local politics, these figures provide valuable insights into the dynamics of political competition and representation.

Explore related products

$24.95 $24.95

What You'll Learn

- Party Affiliation Trends: Analyze shifts in voter party identification over time using historical data

- Demographic Breakdown: Examine party percentages by age, race, gender, and education level

- Geographic Distribution: Map party support across regions, states, or urban vs. rural areas

- Election Impact: Compare party percentages in midterms vs. presidential election years

- Third-Party Influence: Assess the percentage of voters supporting parties beyond the two major ones

Party Affiliation Trends: Analyze shifts in voter party identification over time using historical data

Voter party identification in the United States has undergone significant shifts over the past several decades, reflecting broader societal, economic, and cultural changes. Historical data from organizations like Pew Research Center and Gallup reveal that party affiliation is not static; it ebbs and flows in response to political events, leadership, and demographic evolution. For instance, the Democratic Party dominated affiliation in the mid-20th century, with over 50% of Americans identifying as Democrats in the 1950s. However, by the 2020s, the landscape had shifted, with independents comprising the largest share of the electorate, often leaning toward one party or the other in elections.

Analyzing these trends requires a focus on key inflection points. The 1960s and 1970s, marked by the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War, saw a decline in Democratic affiliation as Southern conservatives began migrating to the Republican Party. Conversely, the 1990s and early 2000s witnessed a resurgence in Democratic identification, particularly among younger voters and minorities, driven by issues like healthcare and social justice. Understanding these shifts involves examining not just raw percentages but the underlying demographics—age, race, education, and geography—that drive them. For example, college-educated voters have increasingly leaned Democratic, while non-college whites have solidified their Republican support.

To track these trends effectively, researchers rely on longitudinal surveys and exit polls. Gallup’s party affiliation data, collected annually since the 1940s, provides a rich resource for identifying patterns. However, interpreting this data requires caution. Short-term fluctuations, such as those following a presidential election or major policy change, can obscure long-term trends. For instance, the Republican Party saw a surge in affiliation after the 2016 election, but this was partly a reaction to Donald Trump’s candidacy rather than a fundamental realignment. Practical tips for analysts include cross-referencing multiple data sources and focusing on five- or ten-year intervals to smooth out noise.

Comparatively, party affiliation trends in the U.S. differ from those in multiparty systems like the U.K. or Germany, where coalitions and smaller parties play a larger role. In the U.S., the two-party system amplifies shifts, as voters often have fewer alternatives. However, the rise of independents—now roughly 40% of the electorate—suggests growing dissatisfaction with both major parties. This trend mirrors global movements toward political fragmentation, though its implications for American governance remain uncertain. For instance, independents often lean toward one party, but their volatility can swing elections, as seen in the 2020 and 2022 midterms.

In conclusion, analyzing party affiliation trends requires a nuanced approach that combines historical context, demographic analysis, and methodological rigor. By studying these shifts, we gain insight into the evolving priorities of the electorate and the forces shaping political landscapes. For practitioners, this means staying attuned to both long-term patterns and short-term disruptions, while for the public, it underscores the dynamic nature of political identity. As demographics continue to change—with younger, more diverse generations entering the electorate—party affiliation will likely remain in flux, making this analysis an essential tool for understanding the future of American politics.

Taylor Swift's Political Leanings: Which Party Does She Support?

You may want to see also

Demographic Breakdown: Examine party percentages by age, race, gender, and education level

Political party affiliations in the United States are not uniformly distributed across demographic groups, revealing distinct patterns that shape the nation's political landscape. Age, for instance, plays a pivotal role in determining party loyalty. Among voters aged 18-29, Democrats consistently hold a significant advantage, often securing upwards of 60% support in recent elections. This trend reverses dramatically as age increases; voters over 65 tend to lean Republican, with approximately 52% aligning with the GOP. This age-based divide underscores the generational gap in political priorities, with younger voters prioritizing issues like climate change and student debt, while older voters often focus on economic stability and healthcare.

Race and ethnicity further stratify party percentages, highlighting the importance of cultural and historical contexts in political identity. African American voters overwhelmingly support the Democratic Party, with over 85% consistently casting ballots for Democratic candidates. Similarly, Hispanic and Latino voters lean Democratic, though with slightly less uniformity, typically around 65-70%. In contrast, white voters are more evenly split, with a slight majority (approximately 54%) favoring Republicans. Asian American voters, though a smaller demographic, show a growing trend toward Democratic support, with about 65% aligning with the party. These racial disparities reflect broader societal issues, including immigration policies, racial justice, and economic opportunities.

Gender also influences party affiliation, though the gap is narrower than in other demographics. Women are more likely to vote Democratic, with about 52% supporting the party, compared to 48% of men. This difference is often attributed to varying stances on issues like reproductive rights, healthcare, and workplace equality. However, the gender gap is not static; it can fluctuate based on election cycles and the prominence of specific issues. For example, the 2020 election saw a slight widening of the gender gap, driven in part by debates over healthcare and the Supreme Court.

Education level emerges as another critical factor in shaping party preferences. College-educated voters increasingly favor Democrats, with roughly 57% supporting the party. Conversely, voters without a college degree are more likely to vote Republican, particularly among white non-college-educated men, who constitute a core GOP demographic. This educational divide reflects differing economic experiences and policy priorities. College graduates often benefit from knowledge-based economies and support progressive policies, while non-college-educated voters may feel left behind by globalization and technological change, aligning with Republican economic nationalism.

To effectively analyze these demographic breakdowns, it’s essential to consider intersectionality—how multiple identities (e.g., race, gender, education) overlap to create unique political perspectives. For instance, college-educated Black women are among the most reliably Democratic voters, while non-college-educated white men are a stronghold for Republicans. Understanding these intersections provides a more nuanced view of voter behavior. Practical tips for interpreting this data include focusing on trends rather than isolated statistics, examining turnout rates alongside party percentages, and staying informed about evolving issues that may shift demographic loyalties. By dissecting these patterns, we gain insight into the complex dynamics driving political polarization and coalition-building in the U.S.

Where to Find Politoad: Region Guide for Pokémon Trainers

You may want to see also

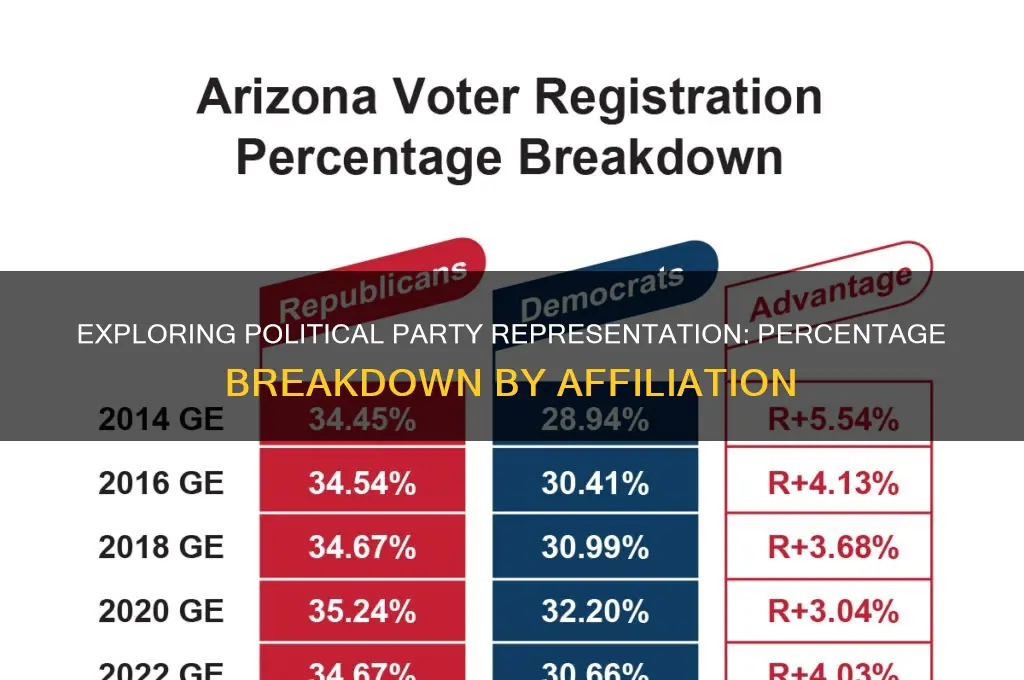

Geographic Distribution: Map party support across regions, states, or urban vs. rural areas

Political party support in the United States is not uniformly distributed; it varies significantly across geographic regions, states, and urban versus rural areas. The so-called "red" and "blue" state divide is a simplification, but it highlights a broader trend: the Republican Party tends to dominate in rural and southern states, while the Democratic Party holds stronger support in urban centers and coastal regions. This geographic polarization has deepened over recent decades, influenced by factors like demographics, economic structures, and cultural values.

To map this distribution effectively, start by examining state-level election results. For instance, the 2020 presidential election showed Democratic strongholds in California, New York, and Illinois, while Republican support was concentrated in Texas, Florida, and the Midwest. However, even within these states, urban areas like Houston and Miami leaned Democratic, while rural counties remained solidly Republican. This urban-rural split is a critical lens for understanding party support, as cities often prioritize issues like public transportation and social services, while rural areas focus on agriculture, gun rights, and local autonomy.

A comparative analysis reveals that the South and Midwest are predominantly Republican, with exceptions like Virginia and Colorado, which have shifted toward Democrats due to urbanization and demographic changes. In contrast, the Northeast and West Coast are largely Democratic, though states like Arizona and Georgia have become battlegrounds due to population growth and diversification. Mapping these trends requires tools like GIS software or interactive online platforms, which can overlay election data with demographic information to identify correlations between party support and factors like education levels, income, and racial composition.

When interpreting these maps, be cautious of oversimplifying regional identities. For example, while Appalachia is often associated with Republican support, pockets of Democratic voters exist in areas with strong labor union histories. Similarly, the Sun Belt’s rapid growth has introduced diverse populations that challenge traditional party alignments. To make these maps actionable, pair them with local polling data and focus groups to understand the nuanced motivations of voters in specific regions.

Finally, consider the practical implications of geographic distribution for political strategies. Campaigns should tailor messaging to regional priorities: emphasizing infrastructure and healthcare in urban areas, while focusing on rural economic development and cultural preservation in less populated regions. By visualizing party support geographically, stakeholders can allocate resources more efficiently, target swing areas, and foster dialogue across ideological divides. This approach transforms static maps into dynamic tools for understanding and engaging the electorate.

Understanding the Role and Impact of Political Opposition in the US

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Election Impact: Compare party percentages in midterms vs. presidential election years

The ebb and flow of political power in the United States is often most visible when comparing midterm and presidential election years. In presidential election years, voter turnout averages around 60%, while midterms see a drop to roughly 40%. This disparity in participation significantly influences the percentage of votes each party secures. Higher turnout in presidential years tends to favor Democrats, as younger and minority voters—key Democratic demographics—are more likely to cast ballots when the presidency is at stake. Conversely, midterms often see a more engaged Republican base, skewing results in their favor.

Analyzing historical data reveals a consistent pattern: the president’s party typically loses ground in midterms. Since World War II, the president’s party has lost an average of 26 House seats and 4 Senate seats in midterm elections. For instance, in 2018 (a midterm year under President Trump), Democrats gained 41 House seats, flipping control of the chamber. Compare this to 2020, a presidential election year, where Democrats maintained a slim House majority and gained one Senate seat. This shift underscores how midterms serve as a referendum on the president’s performance, often penalizing the incumbent party.

To understand why these shifts occur, consider voter behavior. Presidential elections attract a broader electorate, including sporadic voters who lean Democratic. Midterms, however, draw a smaller, more ideologically driven group. For example, in 2010 (a midterm under President Obama), Republicans gained 63 House seats, fueled by Tea Party activism. Practical tip: Campaigns should tailor strategies to these dynamics—in midterms, focus on mobilizing the base; in presidential years, invest in outreach to infrequent voters.

A cautionary note: While midterms often favor the out-of-power party, this isn’t guaranteed. In 2002, Republicans gained seats under President Bush post-9/11, defying the trend. Similarly, external factors like economic conditions or scandals can amplify or mitigate midterm losses. For instance, the 2022 midterms saw Democrats outperform expectations, losing only a narrow House majority, partly due to voter backlash against Republican stances on abortion rights.

In conclusion, comparing party percentages between midterms and presidential years highlights the structural advantages and vulnerabilities of each party. Democrats thrive in high-turnout presidential elections, while Republicans often capitalize on midterm apathy. For voters and strategists alike, understanding these patterns is crucial for predicting outcomes and crafting effective campaigns. Practical takeaway: Track voter registration trends and early voting data to gauge which party’s base is more energized in any given cycle.

Understanding Socio-Political Diversity: A Comprehensive Exploration of Its Meaning and Impact

You may want to see also

Third-Party Influence: Assess the percentage of voters supporting parties beyond the two major ones

In the United States, third-party candidates have historically struggled to gain significant traction, often receiving single-digit percentages of the popular vote. For instance, in the 2020 presidential election, Libertarian candidate Jo Jorgensen secured 1.18% of the vote, while Green Party candidate Howie Hawkins garnered 0.26%. These numbers highlight the dominance of the two-party system, yet they also reveal a persistent, albeit small, segment of voters who reject the major parties. This raises the question: what does this percentage signify, and how does it influence the broader political landscape?

Analyzing these figures requires understanding the structural barriers third parties face, such as ballot access restrictions and winner-take-all electoral systems. Despite these challenges, third-party support can act as a barometer for voter dissatisfaction with the major parties. For example, in 1992, Ross Perot’s independent candidacy captured 18.9% of the vote, reflecting widespread frustration with economic policies. While such high percentages are rare, even smaller shares can force major parties to address issues they might otherwise ignore, such as climate change or campaign finance reform, which have been championed by Green Party and Libertarian candidates, respectively.

To assess third-party influence effectively, consider the following steps: first, examine state-level data, as third-party performance varies significantly by region. States with less restrictive ballot access laws, like New Mexico or Vermont, often see higher third-party vote shares. Second, track demographic trends. Younger voters, aged 18–29, are more likely to support third-party candidates, with polls showing up to 15% of this group favoring alternatives in recent elections. Finally, monitor down-ballot races, where third-party candidates occasionally win local or state offices, demonstrating that their influence extends beyond presidential contests.

Caution must be exercised when interpreting these percentages, as they do not always translate into policy changes or lasting political power. Third-party voters are often ideologically diverse, making it difficult for these parties to coalesce into a unified force. However, their role in shaping public discourse should not be underestimated. For instance, the Libertarian Party’s emphasis on reducing government intervention has pushed both Republicans and Democrats to reconsider certain regulatory policies. Similarly, the Green Party’s focus on environmental issues has contributed to the mainstreaming of climate change as a critical political topic.

In conclusion, while third-party candidates rarely win elections, their percentage of support serves as a vital indicator of voter sentiment and a catalyst for policy innovation. By studying these numbers and their contextual factors, observers can better understand the nuances of American politics and the potential for systemic change. Practical tips for engagement include supporting electoral reforms like ranked-choice voting, which could level the playing field for third parties, and encouraging media coverage of their platforms to amplify their influence.

Andrew Jackson: Founding Leader of the Democratic Party Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

As of 2023, the U.S. Congress is roughly divided with Democrats holding a slim majority in the Senate (51%) and Republicans holding a narrow majority in the House of Representatives (51%).

In the UK Parliament, as of 2023, the Conservative Party holds approximately 56% of seats, while the Labour Party holds around 39%, with smaller parties and independents making up the remaining 5%.

The European Parliament (2023) is dominated by the European People's Party (EPP) with about 25%, followed by the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) with 20%, Renew Europe with 14%, and other groups making up the rest.

In India's Lok Sabha (2023), the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) holds around 45% of seats, the Indian National Congress (INC) holds about 10%, and regional parties and allies make up the remaining 45%.

In Canada's House of Commons (2023), the Liberal Party holds approximately 42% of seats, the Conservative Party holds around 35%, the Bloc Québécois holds 8%, the New Democratic Party (NDP) holds 12%, and smaller parties hold the remaining 3%.