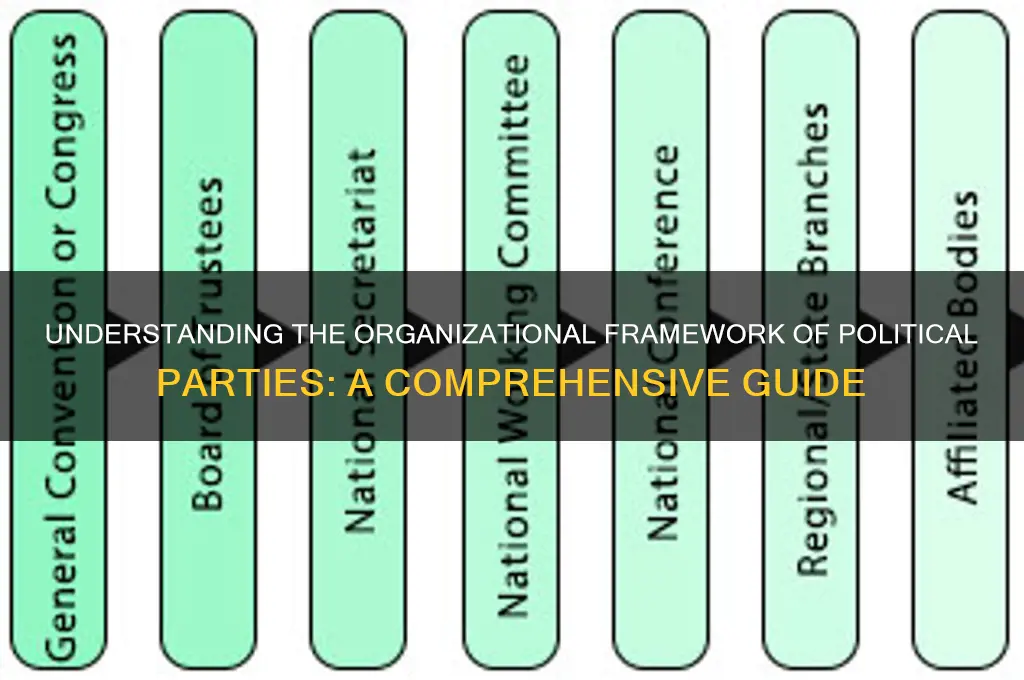

The organizational structure of a political party is a critical framework that defines how the party operates, makes decisions, and achieves its goals. Typically, it consists of hierarchical levels, starting with grassroots members who form the base, followed by local and regional chapters that coordinate activities and mobilize support. Above these are national committees or executive bodies responsible for strategic planning, fundraising, and policy formulation. Leadership roles, such as party chairs, secretaries, and treasurers, ensure accountability and direction, while specialized committees focus on areas like communications, outreach, and candidate recruitment. This structure fosters cohesion, enables efficient resource allocation, and ensures alignment with the party’s ideology and objectives, ultimately shaping its effectiveness in political competition.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Leadership | A political party typically has a hierarchical leadership structure with a party leader or chairperson at the top. This leader is often elected by party members or a central committee and is responsible for setting the party's agenda, strategy, and public image. |

| Central Committee/Executive Board | A governing body that oversees the party's operations, makes key decisions, and manages finances. Members are usually elected by the party's national conference or appointed by the leader. |

| National Conference/Convention | A periodic gathering of party members, delegates, and leaders to discuss policies, elect officials, and set the party's platform. This is often the highest decision-making body within the party. |

| Regional/State/Local Chapters | Decentralized structures at various geographic levels (e.g., state, county, city) to organize members, mobilize voters, and implement party policies locally. Each chapter may have its own leadership and committees. |

| Policy Committees | Specialized groups responsible for developing and refining party policies on specific issues (e.g., economy, healthcare, foreign affairs). These committees often include experts and elected officials. |

| Fundraising and Finance | A dedicated department or committee responsible for raising funds through donations, memberships, and events. Ensures financial sustainability and compliance with campaign finance laws. |

| Communications and Media | Handles public relations, messaging, and media strategy. Includes press officers, social media managers, and speechwriters to promote the party's agenda and respond to public discourse. |

| Campaign Organization | A structured team focused on election campaigns, including strategists, volunteers, and field organizers. Coordinates voter outreach, advertising, and get-out-the-vote efforts. |

| Membership and Activism | The base of the party, comprising individual members and activists who participate in events, canvassing, and policy discussions. Membership fees and engagement are crucial for party funding and grassroots support. |

| Youth and Special Interest Wings | Sub-organizations focused on engaging specific demographics (e.g., youth, women, minorities) or promoting particular causes within the party's framework. |

| International Affiliations | Some parties are affiliated with international organizations or alliances (e.g., Socialist International, Liberal International) to coordinate global policies and share resources. |

| Discipline and Ethics | Mechanisms to ensure members adhere to party principles and codes of conduct. May include disciplinary committees to address internal disputes or misconduct. |

| Technology and Data | Increasingly important for modern parties, this includes digital tools for voter data analysis, online campaigning, and member engagement platforms. |

Explore related products

$1.99 $24.95

$15.97 $21.95

What You'll Learn

- Leadership Hierarchy: Examines roles like chair, secretary, treasurer, and their decision-making authority within the party

- Local vs. National Structure: Explores how regional chapters interact with central leadership and policy-making bodies

- Committees and Subgroups: Analyzes specialized groups focused on policy, fundraising, campaigns, or outreach efforts

- Membership and Participation: Discusses how members join, engage, and influence party decisions or candidate selection

- Decision-Making Processes: Investigates methods like voting, consensus, or top-down directives in shaping party actions

Leadership Hierarchy: Examines roles like chair, secretary, treasurer, and their decision-making authority within the party

At the heart of any political party's organizational structure lies its leadership hierarchy, a framework that delineates roles, responsibilities, and decision-making authority. Among the most critical positions are the chair, secretary, and treasurer, each serving distinct functions that collectively ensure the party’s operational efficiency and strategic direction. These roles are not merely ceremonial; they form the backbone of the party’s governance, influencing everything from policy formulation to financial management.

Consider the chair, often the public face of the party, whose primary responsibility is to provide strategic leadership and vision. This individual typically presides over meetings, represents the party in public forums, and makes high-level decisions in consultation with other leaders. However, the chair’s authority is not absolute; it is often balanced by the need for consensus-building within the party’s executive committee. For instance, in the UK’s Conservative Party, the chair works closely with the leader and other senior officials to shape campaign strategies and policy priorities, demonstrating a collaborative rather than autocratic leadership style.

The secretary, on the other hand, is the party’s administrative linchpin. This role involves maintaining records, organizing meetings, and ensuring compliance with internal rules and external regulations. While the secretary may not wield the same level of decision-making authority as the chair, their organizational prowess is indispensable for the party’s day-to-day operations. In the Democratic Party in the United States, for example, the secretary plays a crucial role in coordinating state and local chapters, ensuring alignment with national objectives.

Equally vital is the treasurer, whose primary duty is to manage the party’s finances. This includes budgeting, fundraising, and ensuring transparency in financial transactions. The treasurer’s decision-making authority is often confined to financial matters but can significantly impact the party’s ability to execute campaigns and initiatives. In Canada’s Liberal Party, the treasurer works closely with the fundraising committee to allocate resources effectively, highlighting the role’s strategic importance beyond mere bookkeeping.

A comparative analysis reveals that while these roles are universal across political parties, their specific authorities and responsibilities can vary based on the party’s size, ideology, and cultural context. For instance, in smaller parties, the chair may have broader decision-making powers, while in larger, more decentralized parties, authority is often distributed among multiple leaders. Understanding these nuances is essential for anyone seeking to navigate or reform a party’s internal structure.

In conclusion, the leadership hierarchy of a political party is a dynamic and multifaceted system, with the chair, secretary, and treasurer playing complementary yet distinct roles. Their collective effectiveness hinges on clear role definitions, balanced authority, and collaborative decision-making. By examining these roles in detail, one gains insight into the intricate mechanisms that drive political organizations and shape their impact on the broader political landscape.

Texas Politics: The Dominant Forces Shaping the Lone Star State

You may want to see also

Local vs. National Structure: Explores how regional chapters interact with central leadership and policy-making bodies

Political parties are not monolithic entities; they are complex organisms with a delicate balance between local autonomy and national cohesion. At the heart of this dynamic is the relationship between regional chapters and central leadership, a relationship that can make or break a party's effectiveness. Local chapters, often the grassroots of a party, are where policies meet people, and national leadership, the strategic brain, sets the overarching agenda. How these two interact determines a party's ability to adapt to diverse regional needs while maintaining a unified front.

Consider the Democratic Party in the United States, where state and local chapters play a pivotal role in mobilizing voters and tailoring national messages to resonate with regional issues. For instance, in rural areas, local chapters might emphasize agricultural policies, while urban chapters focus on public transportation. This adaptability is crucial, but it requires a structured system of communication and feedback between local and national bodies. Without it, local chapters risk becoming disconnected from the party’s core values, while national leadership may appear out of touch with grassroots concerns.

To ensure effective interaction, parties often establish formal mechanisms such as regional representatives in national committees, regular policy consultations, and decentralized fundraising models. For example, the Conservative Party in the U.K. has a system where local associations elect representatives to the party’s board, ensuring regional voices are heard in decision-making. Conversely, in Germany’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU), local chapters have significant autonomy in candidate selection, but national leadership retains control over key policy platforms. These models highlight the importance of striking a balance between local flexibility and national consistency.

However, challenges arise when local priorities clash with national agendas. A party’s ability to navigate these tensions often hinges on its internal governance structure. For instance, in India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), local units are highly active in community engagement, but they must align with the central leadership’s ideological framework. This alignment is enforced through regular training programs and a hierarchical reporting system, ensuring that local efforts reinforce national goals. Such strategies demonstrate that effective interaction requires both autonomy and accountability.

In practice, parties must adopt a dual approach: empower local chapters to address unique regional needs while integrating their insights into national policy-making. This can be achieved through regular town hall meetings, digital platforms for feedback, and joint policy workshops. For smaller parties or those in developing nations, resource constraints may limit such initiatives, making it essential to prioritize cost-effective methods like social media engagement or volunteer networks. Ultimately, the strength of a political party lies in its ability to harmonize local dynamism with national vision, creating a structure that is both responsive and resilient.

Understanding Voter Perception: How People Identify Political Parties

You may want to see also

Committees and Subgroups: Analyzes specialized groups focused on policy, fundraising, campaigns, or outreach efforts

Within the intricate machinery of a political party, committees and subgroups serve as the specialized engines driving focused efforts. These are not mere bureaucratic appendages but dynamic units, each with a distinct mandate. The Policy Committee, for instance, is the intellectual powerhouse, tasked with crafting and refining the party’s stance on issues ranging from healthcare to foreign policy. Its members, often experts in their fields, dissect complex problems and propose solutions that align with the party’s ideology. Without this group, the party’s platform would lack depth and coherence, leaving it vulnerable to criticism and voter skepticism.

Contrast the Policy Committee with the Fundraising Subcommittee, a group laser-focused on the financial lifeblood of the party. Here, the emphasis is on strategy—identifying high-net-worth donors, organizing events, and leveraging digital platforms to maximize contributions. A successful fundraising team understands the art of persuasion, balancing transparency with the need to secure resources. For example, a well-executed gala dinner can bring in six-figure donations, but only if the subcommittee has meticulously planned every detail, from guest lists to follow-up communications. Neglect this group, and the party risks financial instability, hindering its ability to run effective campaigns.

Campaign Subgroups, on the other hand, are the boots on the ground, orchestrating the logistics of elections. These teams coordinate voter registration drives, manage volunteer networks, and deploy data analytics to target swing districts. A key tactic here is micro-targeting, where voter data is segmented to deliver tailored messages. For instance, a subgroup might use demographic data to craft messages about education reform for suburban parents or job creation for urban youth. Without such precision, campaigns risk wasting resources on uninterested voters or failing to mobilize their base.

Outreach Committees play a different but equally vital role, acting as the party’s bridge to diverse communities. These groups focus on building relationships with minority groups, youth, and other underrepresented demographics. Effective outreach involves more than just translating campaign materials; it requires cultural sensitivity and genuine engagement. For example, a Latino Outreach Subcommittee might partner with local organizations to host town halls, ensuring the party’s message resonates with the community’s unique concerns. Fail to prioritize this, and the party risks alienating key voter blocs, limiting its electoral appeal.

In practice, the interplay between these committees and subgroups is critical. A policy proposal, for instance, must be vetted by the Policy Committee, funded by the Fundraising Subcommittee, promoted by the Campaign Subgroup, and disseminated by the Outreach Committee. This collaborative model ensures that efforts are synchronized, resources are maximized, and the party’s message remains consistent. However, friction can arise if communication breaks down—a policy that lacks funding or a campaign that ignores outreach efforts will fall short. The takeaway is clear: these specialized groups are not silos but interconnected cogs in the party’s organizational machine, each indispensable in their own right.

Unveiling MLK's Political Party: A Deep Dive into His Affiliations

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Membership and Participation: Discusses how members join, engage, and influence party decisions or candidate selection

Political parties thrive on the energy and commitment of their members, yet the pathways to joining and participating vary widely. In the United States, for instance, becoming a member of the Democratic or Republican Party often begins with registering as an affiliate during voter registration. This simple act grants individuals access to party primaries, a critical juncture where members directly influence candidate selection. Contrast this with Germany’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU), where membership requires a formal application, payment of dues, and adherence to party principles. These differences highlight how structural design shapes the ease or difficulty of entry, which in turn affects the diversity and size of the membership base.

Engagement within a party is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. In the UK’s Labour Party, members participate through local constituency meetings, policy forums, and annual conferences, where they can propose and vote on resolutions. This grassroots approach empowers members to shape party direction. Conversely, France’s La République En Marche! leverages digital platforms, encouraging members to contribute ideas and participate in online consultations. Such methods cater to younger, tech-savvy demographics but may exclude those less comfortable with digital tools. The takeaway? Parties must balance traditional and modern engagement strategies to maximize participation across diverse membership profiles.

Influence over party decisions and candidate selection is the ultimate measure of membership value. In Canada’s New Democratic Party (NDP), members have a direct say in electing the party leader through a weighted voting system, ensuring regional representation. This contrasts with Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), where faction leaders and senior officials dominate decision-making, leaving ordinary members with limited sway. Such disparities underscore the importance of transparency and inclusivity in party structures. Parties that democratize decision-making processes not only foster member loyalty but also enhance their legitimacy in the eyes of the public.

To maximize their impact, members should strategically navigate party structures. Attend local meetings consistently to build relationships and credibility. Leverage digital tools to amplify your voice in policy discussions. For those aiming to influence candidate selection, join campaign committees or volunteer for fundraising efforts—these roles often grant insider access. Caution, however, against overcommitting without understanding the party’s power dynamics; some decisions remain firmly in the hands of elites. Ultimately, effective participation requires a blend of enthusiasm, strategic engagement, and realistic expectations.

Media and Political Parties: Pillars of Democracy or Power Brokers?

You may want to see also

Decision-Making Processes: Investigates methods like voting, consensus, or top-down directives in shaping party actions

Decision-making within political parties is a critical function that determines their responsiveness, unity, and effectiveness. Methods like voting, consensus-building, and top-down directives each carry distinct advantages and limitations, shaping how parties navigate internal conflicts and external challenges. Voting, for instance, is a democratic cornerstone, allowing members to express preferences directly. However, it can lead to majority rule overshadowing minority voices, fostering division if not managed carefully. In contrast, consensus-seeking prioritizes unity by requiring unanimous or near-unanimous agreement, but it risks inefficiency and watered-down policies in the pursuit of compromise. Top-down directives, often employed in hierarchical parties, ensure swift action but may alienate grassroots members, stifling creativity and engagement. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for parties aiming to balance efficiency, inclusivity, and coherence in their decision-making processes.

Consider the practical implementation of these methods. Voting systems vary widely, from simple majority votes to weighted systems that account for membership tenure or financial contributions. For example, the Democratic Party in the United States employs a delegate system in presidential primaries, where votes are apportioned based on state-level results, blending direct democracy with proportional representation. Consensus-building, on the other hand, often involves facilitated discussions, caucuses, or iterative proposals to address concerns. Germany’s Green Party is a notable example, using consensus to align decisions with their core principles, though this approach can extend deliberation timelines significantly. Top-down directives are common in parties with strong leadership figures, such as the Bharatiya Janata Party in India, where central leadership often sets the agenda, ensuring alignment but at the risk of suppressing dissent.

When selecting a decision-making method, parties must weigh their goals and context. For instance, a party prioritizing rapid response to crises might favor top-down directives, while one focused on grassroots engagement may opt for consensus or voting mechanisms. Hybrid models, combining elements of each approach, are increasingly popular. The Labour Party in the UK, for example, uses a mix of voting at party conferences and leadership directives, balancing member input with strategic coherence. However, such hybrids require clear rules to prevent confusion or power struggles. Parties should also consider the age and technological savvy of their members; younger demographics may prefer digital voting platforms, while older members might favor traditional in-person methods.

A critical caution is the potential for decision-making processes to become tools of manipulation. Voting systems can be gamed through gerrymandering or voter suppression within party structures, while consensus-building can be hijacked by vocal minorities. Top-down directives, meanwhile, risk becoming authoritarian if unchecked. To mitigate these risks, parties should establish transparent rules, independent oversight bodies, and mechanisms for appealing decisions. For example, the Swedish Social Democratic Party uses an ethics committee to review leadership actions, ensuring accountability. Additionally, parties should regularly evaluate their processes through feedback surveys or performance metrics, such as decision speed, member satisfaction, and policy effectiveness.

In conclusion, the choice of decision-making process is a defining feature of a political party’s organizational structure, influencing its internal dynamics and external impact. Parties must tailor their approach to their values, goals, and membership demographics, while remaining vigilant against abuses of power. By studying examples like the U.S. Democratic Party’s delegate system or the Green Party’s consensus model, parties can design processes that foster unity, responsiveness, and legitimacy. Ultimately, the strength of a party lies not just in its decisions, but in how those decisions are made.

Exploring Alabama's Political Landscape: Which Party Dominates the State?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The organizational structure of a political party typically includes local, regional, and national levels, with committees, leaders, and members working together to achieve the party’s goals.

Key leaders include the party chairperson, secretary, treasurer, and spokespersons, who oversee operations, fundraising, communication, and policy development.

Decisions are often made through a combination of executive committee meetings, party conferences, and voting by members or delegates, depending on the party’s bylaws.

Grassroots members are essential for local organizing, campaigning, fundraising, and representing the party’s values at the community level, often forming the foundation of the party’s support base.