Political soft money refers to financial contributions made to political parties, candidates, or organizations that are not subject to federal campaign finance regulations, allowing for larger and often undisclosed donations. Unlike hard money, which is strictly regulated and limited in amount, soft money is typically used for party-building activities, voter registration, and issue advocacy rather than directly supporting or opposing a specific candidate. This type of funding gained prominence in the United States following the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, which aimed to restrict its use due to concerns about its potential to circumvent campaign finance laws and influence political outcomes without transparency. Despite legal reforms, soft money continues to play a significant role in American politics, often through loopholes and alternative channels like 501(c)(4) organizations, raising ongoing debates about its impact on democratic integrity and accountability.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Funds raised for political purposes but not directly contributed to candidates or parties. |

| Legal Status | Legal under certain conditions, regulated by campaign finance laws. |

| Primary Use | Used for party-building activities, voter registration, and issue advocacy. |

| Contribution Limits | Typically no limits on contributions, unlike hard money. |

| Donor Disclosure | Disclosure requirements vary; often less stringent than hard money. |

| Prohibited Uses | Cannot be used for direct candidate support or campaign coordination. |

| Examples of Use | Funding ads that mention issues but not candidates, party infrastructure. |

| Regulatory Body | Federal Election Commission (FEC) in the U.S. |

| Controversy | Criticized for enabling potential circumvention of campaign finance laws. |

| Recent Trends | Increasing scrutiny and calls for stricter regulations in many countries. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Origins: Soft money refers to unregulated funds for party-building, not directly for candidates

- Legal Framework: Governed by looser laws compared to hard money, often used in issue advocacy

- Sources of Soft Money: Corporations, unions, and wealthy individuals contribute significantly to soft money pools

- Impact on Elections: Influences elections indirectly by funding ads, voter drives, and party operations

- Controversies and Reforms: Critics argue it allows corruption; reforms aim to limit its influence

Definition and Origins: Soft money refers to unregulated funds for party-building, not directly for candidates

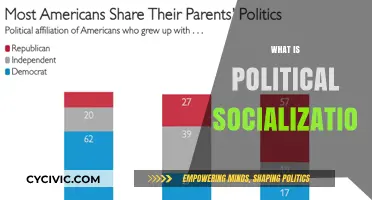

Soft money, a term that emerged in the late 20th century, refers to financial contributions made to political parties for party-building activities, rather than directly to candidates or their campaigns. This distinction is crucial, as it allows such funds to bypass the strict regulations and contribution limits imposed by campaign finance laws. The origins of soft money can be traced back to the 1970s, when the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) established limits on direct contributions to federal candidates. Political parties, seeking alternative avenues for funding, began accepting unlimited donations for non-federal accounts, which were ostensibly designated for party-building efforts, voter registration, and issue advocacy.

The rise of soft money was, in part, a response to the increasing costs of political campaigns and the need for parties to maintain a strong organizational infrastructure. By funneling funds through state party committees or affiliated organizations, parties could support their candidates indirectly, while avoiding the scrutiny and restrictions associated with direct campaign contributions. This practice became particularly prominent in the 1990s, when both major U.S. political parties established national committees dedicated to raising and distributing soft money. For instance, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and the Republican National Committee (RNC) created non-federal accounts that accepted large donations from corporations, unions, and individuals, which were then used to fund get-out-the-vote efforts, television ads, and other party-building activities.

One of the key characteristics of soft money is its lack of regulation, which has led to concerns about transparency and accountability. Unlike hard money contributions, which are subject to strict reporting requirements and contribution limits, soft money donations often operate in a gray area, with minimal disclosure obligations. This opacity has raised questions about the potential for undue influence, as large donors may seek to shape party policies or gain access to elected officials in exchange for their financial support. Critics argue that soft money undermines the principles of fair and equitable campaign financing, creating an uneven playing field that favors wealthy interests over ordinary citizens.

To address these concerns, lawmakers have attempted to regulate soft money through legislative and judicial means. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002, also known as the McCain-Feingold Act, sought to close the soft money loophole by banning national political parties from raising or spending soft money. However, the law faced legal challenges, and the Supreme Court's 2010 decision in *Citizens United v. FEC* further complicated the landscape by allowing corporations and unions to spend unlimited amounts on political advertising, as long as it was not coordinated with candidates. Despite these efforts, soft money continues to play a significant role in American politics, highlighting the ongoing tension between the need for robust party-building and the imperative of maintaining a transparent and accountable political system.

In practical terms, understanding soft money requires a nuanced appreciation of its historical context, legal framework, and real-world implications. For individuals interested in political fundraising or advocacy, it is essential to distinguish between hard and soft money contributions, as well as to stay informed about evolving regulations and court decisions. Organizations seeking to engage in party-building activities should prioritize transparency and ethical practices, even in the absence of strict legal requirements. By doing so, they can help foster a political environment that values fairness, accountability, and the public interest, while still supporting the vital work of strengthening political parties and promoting democratic participation.

Breaking Free: My Journey to Escape Political Turmoil and Find Peace

You may want to see also

Legal Framework: Governed by looser laws compared to hard money, often used in issue advocacy

Political soft money operates within a legal framework that contrasts sharply with the stricter regulations governing hard money. Unlike hard money, which is directly contributed to candidates or political parties with strict limits and disclosure requirements, soft money is subject to far looser laws. This distinction allows soft money to flow more freely, often funding issue advocacy rather than directly supporting candidates. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002, also known as the McCain-Feingold Act, attempted to curb soft money by banning its use in federal elections, but loopholes and alternative channels have kept it relevant in state and local politics.

To understand the legal framework, consider the regulatory differences. Hard money contributions are capped—for example, individuals could contribute up to $2,900 per candidate per election cycle in 2022—and must be disclosed to the Federal Election Commission (FEC). Soft money, however, faces no such limits and is often funneled through organizations like 527 groups or 501(c)(4) nonprofits, which are not required to disclose donors. This opacity makes soft money a powerful tool for issue advocacy, allowing donors to influence political discourse without the constraints of hard money regulations. For instance, a 501(c)(4) organization can run ads advocating for or against a policy without explicitly endorsing a candidate, staying within legal bounds.

A practical example illustrates the flexibility of soft money. In the 2018 midterm elections, a 501(c)(4) group spent millions on ads highlighting the benefits of renewable energy, a position aligned with Democratic candidates. While the ads did not mention specific candidates, their timing and content clearly aimed to sway public opinion in favor of Democratic policies. This is a classic use of soft money in issue advocacy, leveraging looser laws to influence political outcomes indirectly. Such tactics underscore the importance of understanding the legal framework to navigate its complexities effectively.

However, the lack of transparency in soft money raises ethical and practical concerns. Critics argue that it allows wealthy donors and special interests to wield disproportionate influence without accountability. For instance, a single donor could contribute unlimited amounts to a 527 group, which then funds ads attacking a candidate’s stance on healthcare, all without disclosing the donor’s identity. This opacity can distort public discourse and undermine trust in the political process. To mitigate these risks, advocates for reform propose stricter disclosure requirements and clearer definitions of issue advocacy to prevent circumvention of existing laws.

In conclusion, the legal framework governing soft money is a double-edged sword. Its looser regulations enable robust issue advocacy, providing a platform for diverse voices in political debates. Yet, the lack of transparency and accountability creates opportunities for abuse. Navigating this landscape requires a nuanced understanding of the laws and their limitations. For organizations and donors, adhering to ethical standards while leveraging soft money’s flexibility is key. For policymakers, striking a balance between free speech and transparency remains an ongoing challenge in shaping the future of political financing.

Understanding Political Economists: Roles, Impact, and Global Influence Explained

You may want to see also

Sources of Soft Money: Corporations, unions, and wealthy individuals contribute significantly to soft money pools

Political soft money, by definition, operates outside the direct campaign contribution limits set by federal law. This creates a fertile ground for corporations, unions, and wealthy individuals to exert disproportionate influence on the political process. Their contributions, often substantial, flow into party committees, issue advocacy groups, and other entities not directly tied to specific candidates.

Imagine a political landscape where a single corporation can donate millions to a party committee, effectively shaping the party's agenda and gaining preferential access to lawmakers. This is the reality of soft money.

Corporations, driven by their bottom line, leverage these contributions to advocate for policies favorable to their industries. Unions, representing the collective voice of workers, use soft money to push for labor-friendly legislation and protect their members' interests. Wealthy individuals, motivated by ideological beliefs or personal gain, can amplify their political voice far beyond that of the average citizen.

The mechanics are straightforward. Corporations and unions often establish Political Action Committees (PACs) to pool resources and make soft money donations. Wealthy individuals can contribute directly to party committees or independent expenditure groups. These groups then use the funds for voter mobilization, issue advertising, and other activities that indirectly benefit candidates aligned with their interests.

While legal, the system raises serious concerns about fairness and transparency. The sheer volume of soft money contributions can drown out the voices of ordinary citizens, creating a system where political access is bought rather than earned.

Consider the 2004 election cycle, where soft money contributions reached record highs, with corporations and unions pouring millions into issue ads and get-out-the-vote efforts. This influx of money undoubtedly influenced the outcome of key races, highlighting the power of soft money to distort the democratic process.

The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002 attempted to address these concerns by banning unlimited soft money donations to national party committees. However, loopholes remain, allowing soft money to continue flowing through other channels. Ultimately, the issue of soft money highlights the ongoing struggle to balance free speech rights with the need for a fair and equitable political system. Until more comprehensive reforms are enacted, corporations, unions, and wealthy individuals will continue to wield disproportionate influence through their contributions to soft money pools.

Is BLM Political Speech? Exploring the Intersection of Activism and Politics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$11.88 $17.99

Impact on Elections: Influences elections indirectly by funding ads, voter drives, and party operations

Political soft money, often channeled through political parties, 501(c)(4) organizations, and other non-profit groups, operates outside the direct contribution limits set by federal election laws. Unlike hard money, which is strictly regulated and goes directly to candidates or campaigns, soft money is used to influence elections indirectly. This distinction allows it to fund activities that shape public opinion, mobilize voters, and support party infrastructure without explicitly advocating for a specific candidate. By financing ads, voter drives, and party operations, soft money becomes a powerful tool in the electoral process, often tipping the scales in favor of those who can leverage it effectively.

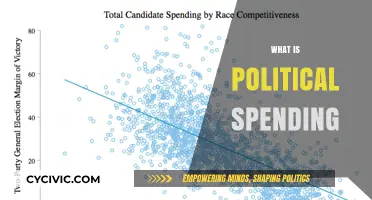

Consider the role of advertising in modern elections. Soft money enables the creation and dissemination of issue-based ads that, while not explicitly endorsing a candidate, subtly promote a party’s agenda or criticize opponents. For instance, during the 2000 U.S. presidential election, soft money funded ads focusing on broad issues like education and healthcare, which indirectly benefited candidates aligned with those positions. These ads, often aired in battleground states, can sway undecided voters by framing the narrative around key issues. The lack of direct regulation on soft money means such ads can be produced and aired in high volumes, saturating media markets and influencing voter perceptions without triggering campaign finance violations.

Voter drives, another critical area funded by soft money, are designed to increase turnout among specific demographics. These drives often target low-propensity voters, such as young adults (ages 18–29) or minority communities, through door-to-door canvassing, phone banking, and digital outreach. For example, in the 2018 midterm elections, soft money-backed organizations registered over 500,000 new voters in key states like Florida and Texas. By focusing on registration and turnout, these efforts can shift the electoral landscape, particularly in close races where a few thousand votes can determine the outcome. The indirect nature of soft money allows these drives to operate at scale without being subject to the same scrutiny as direct campaign contributions.

Party operations, the backbone of any political campaign, also benefit significantly from soft money. Funds are used to maintain offices, hire staff, conduct research, and organize events. For instance, during the 2016 election cycle, soft money helped the Democratic and Republican parties establish field offices in critical states months before the general election, giving them a head start in organizing volunteers and coordinating messaging. This long-term investment in infrastructure creates a strategic advantage, as well-organized parties can respond more effectively to campaign developments and mobilize resources when needed. While these activities do not directly advocate for candidates, they create an environment conducive to electoral success.

The cumulative impact of soft money on elections is profound but often subtle. By funding ads, voter drives, and party operations, it shapes the electoral playing field in ways that are difficult to quantify but impossible to ignore. Critics argue that this system allows wealthy donors and special interests to exert disproportionate influence, while proponents claim it fosters robust political participation. Regardless of perspective, understanding how soft money operates is essential for anyone seeking to navigate or reform the modern electoral landscape. Its indirect nature makes it a versatile and potent force, one that continues to evolve alongside campaign finance laws and political strategies.

Understanding China's Political System: Structure, Ideology, and Global Influence

You may want to see also

Controversies and Reforms: Critics argue it allows corruption; reforms aim to limit its influence

Political soft money, often funneled through loopholes in campaign finance laws, has become a lightning rod for controversy. Critics argue it undermines the very foundation of democratic elections by allowing wealthy individuals and special interests to exert disproportionate influence. Unlike "hard money," which is directly contributed to candidates and strictly regulated, soft money flows to political parties for "party-building activities," a vague category that often includes issue ads and get-out-the-vote efforts that conveniently benefit specific candidates. This distinction, while seemingly technical, creates a gaping hole in transparency and accountability.

The consequences are stark. Consider the 2000 presidential election, where millions in soft money flooded into both major parties, often from undisclosed sources. This lack of transparency fuels public distrust, as citizens are left wondering whose interests are truly being served by their elected officials.

Reforms aimed at curbing soft money's influence have been met with fierce resistance. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002, also known as the McCain-Feingold Act, sought to close the soft money loophole by banning national political parties from raising or spending soft money. While initially hailed as a victory for campaign finance reform, the Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United v. FEC decision dealt a significant blow. The ruling allowed corporations and unions to spend unlimited amounts on independent political expenditures, effectively creating new avenues for undisclosed money to influence elections.

This cat-and-mouse game between reformers and those seeking to exploit loopholes highlights the complexity of regulating political spending.

Despite these challenges, efforts to limit the influence of soft money continue. Some advocate for public financing of elections, where candidates receive public funds in exchange for agreeing to strict spending limits. Others push for stricter disclosure requirements, forcing organizations to reveal the sources of their funding. These reforms, while not without their own complexities, offer potential pathways towards a more transparent and accountable political system. Ultimately, the debate over soft money boils down to a fundamental question: who should have the loudest voice in our democracy – the people, or those with the deepest pockets?

Lawyers in Politics: Exploring Their Role and Influence in Governance

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political soft money refers to financial contributions made to political parties or organizations that are not subject to federal contribution limits or source restrictions. It is typically used for party-building activities, voter registration, and issue advocacy rather than directly supporting specific candidates.

Soft money is used for general party activities and is not regulated by federal contribution limits, while hard money is directly contributed to candidates or campaigns and is strictly regulated by the Federal Election Commission (FEC) in terms of amount and source.

The legality of soft money has evolved. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002 banned national political parties from raising or spending soft money, but it remains legal for state parties, nonprofit organizations, and certain political action committees (PACs) under specific conditions.

Soft money is controversial because it can allow wealthy individuals, corporations, and special interests to exert disproportionate influence on political parties and elections, potentially circumventing campaign finance regulations designed to prevent corruption and ensure transparency.