Political socialization is the process through which individuals acquire political values, beliefs, and behaviors, shaping their understanding of and engagement with the political world. It begins in early childhood and continues throughout life, influenced by various agents such as family, education, media, peers, and cultural environments. These agents transmit norms, ideologies, and attitudes that form the foundation of an individual’s political identity, whether they align with conservative, liberal, or other political perspectives. The process is not uniform; it varies across societies, generations, and personal experiences, reflecting the dynamic interplay between individual agency and societal structures. Understanding political socialization is crucial for comprehending how citizens develop their political orientations, participate in civic life, and contribute to the broader political landscape.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The process by which individuals acquire political values, beliefs, and behaviors, shaping their understanding of politics and civic engagement. |

| Agents of Socialization | Family, education system, peers, media, religious institutions, and community. |

| Lifelong Process | Occurs throughout life, though early childhood and adolescence are critical periods. |

| Cultural Influence | Shaped by cultural norms, traditions, and historical context of a society. |

| Political Environment | Influenced by the political system, stability, and democratic or authoritarian nature of the regime. |

| Individual Variation | Varies based on personal experiences, socioeconomic status, and psychological factors. |

| Normalization of Norms | Teaches acceptance of societal norms, laws, and political institutions as legitimate. |

| Critical Thinking Development | Encourages or discourages questioning of political systems and authority, depending on the context. |

| Civic Engagement | Fosters participation in voting, activism, and community involvement. |

| Global vs. Local Focus | Can emphasize national, regional, or global political perspectives. |

| Technological Impact | Increasingly influenced by social media, digital platforms, and online discourse. |

| Resistance and Adaptation | Individuals may resist or adapt to political socialization based on personal beliefs or external influences. |

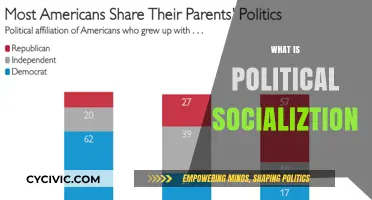

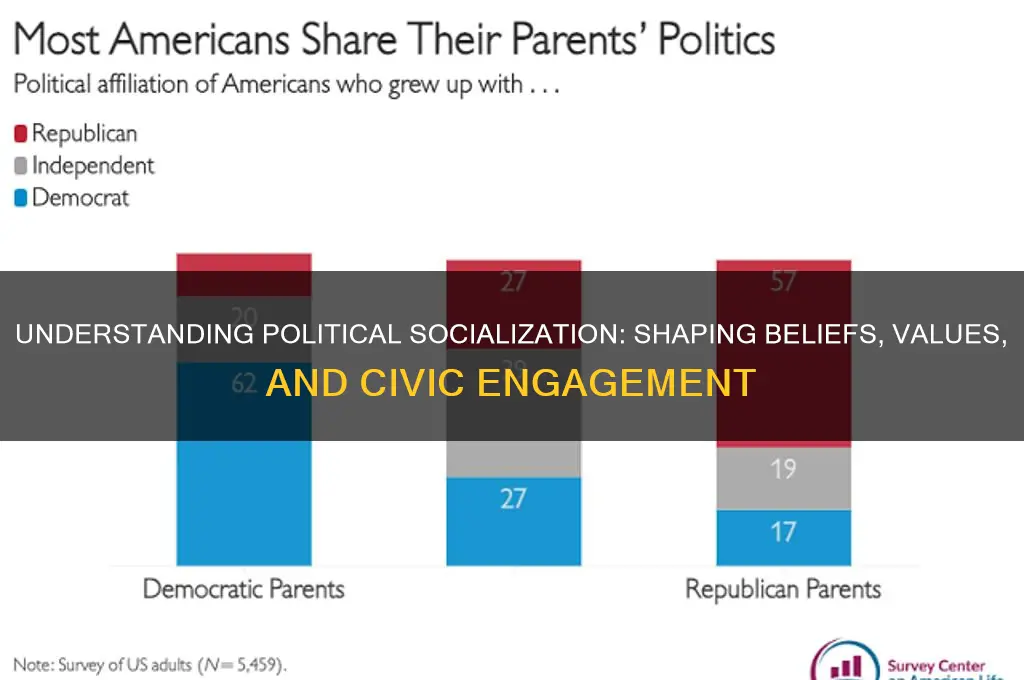

| Intergenerational Transmission | Political beliefs are often passed down from parents to children. |

| Role of Education | Formal education plays a key role in teaching civic duties and political knowledge. |

| Media Influence | News outlets, social media, and entertainment shape political perceptions and attitudes. |

| Crisis and Change | Political socialization can intensify or shift during times of crisis, revolution, or significant social change. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Family Influence: Parents, siblings, and relatives shape early political beliefs and values

- Education Role: Schools and curricula impact political knowledge and attitudes

- Media Impact: News, social media, and entertainment influence political perspectives

- Peer Groups: Friends and social circles reinforce or challenge political views

- Cultural Norms: Societal traditions and practices mold political identities and behaviors

Family Influence: Parents, siblings, and relatives shape early political beliefs and values

The family unit serves as the primary incubator for political socialization, where children absorb beliefs and values often without conscious effort. Parents, through daily conversations, reactions to news, and even casual remarks, subtly embed political perspectives into their children’s worldview. For instance, a parent’s consistent praise or criticism of a political party during dinner-table discussions can shape a child’s early affinity or aversion to that group. Siblings, too, play a role by modeling behaviors and attitudes, often amplifying or challenging parental views. Relatives, during holidays or gatherings, contribute by sharing anecdotes or opinions that reinforce or complicate these emerging beliefs. This process is so pervasive that studies show children as young as 5 can articulate political preferences aligned with their family’s leanings.

Consider the mechanics of this influence: children spend approximately 2,000 waking hours per year with family during their formative years (ages 5–12), a period when cognitive and social development is most impressionable. Parents who actively discuss politics or engage in civic activities—voting, protesting, or volunteering—provide tangible examples of political participation. Conversely, families that avoid political discourse may inadvertently teach apathy or disengagement. Siblings, particularly older ones, act as intermediaries, translating parental values into peer-relevant language. For example, an older sibling might explain a parent’s stance on taxation in terms of fairness or inequality, making abstract concepts relatable. This familial ecosystem creates a layered learning environment where political beliefs are not just taught but lived.

To harness this influence constructively, parents can adopt specific strategies. First, encourage open dialogue rather than monologue. Ask children questions like, “What do you think about this policy?” to foster critical thinking. Second, expose them to diverse viewpoints by inviting relatives with differing opinions to share their perspectives respectfully. Third, model respectful disagreement; children learn more from how parents handle political differences than from the positions themselves. For instance, a parent might say, “I disagree with this policy, but I understand why others support it,” teaching nuance and empathy. These practices transform the family from a passive transmitter of beliefs into an active educator of political engagement.

A cautionary note: unchecked family influence can lead to political rigidity. Children who grow up in politically homogeneous households may struggle to adapt to diverse viewpoints later in life. A study by the American Political Science Association found that individuals with one-sided familial political exposure are 30% less likely to change their political beliefs as adults. To mitigate this, families can introduce structured debates or assign children to research and present opposing views. For example, a 10-year-old might be tasked with explaining both sides of a local election issue, fostering intellectual flexibility. Balancing consistency with exposure to diversity ensures that family influence nurtures informed, adaptable citizens rather than ideological echo chambers.

Ultimately, the family’s role in political socialization is both profound and practical. It is not about indoctrination but about equipping children with the tools to navigate a complex political landscape. By understanding the mechanisms of familial influence—the hours spent together, the modeling of behaviors, the opportunities for dialogue—parents and relatives can intentionally shape a child’s political foundation. This foundation, when built on openness and critical thinking, becomes a springboard for lifelong civic engagement rather than a straitjacket of inherited beliefs. In this way, the family is not just a starting point for political socialization but a dynamic, ongoing partner in its development.

Understanding Irish Politics: A Comprehensive Guide to Its Unique System

You may want to see also

Education Role: Schools and curricula impact political knowledge and attitudes

Schools serve as primary agents of political socialization, systematically shaping students’ understanding of civic norms, governance, and their role within society. Through structured curricula, students are introduced to foundational concepts such as democracy, citizenship, and the rule of law. For instance, in the United States, the study of the Constitution and Bill of Rights in middle and high school civics classes provides a framework for understanding individual rights and governmental responsibilities. Similarly, in countries like Germany, history curricula emphasize the dangers of authoritarianism by examining the Nazi era, fostering a commitment to democratic values. These lessons are not merely informational; they are designed to cultivate attitudes and behaviors that align with the political culture of the nation.

The design of curricula often reflects the ideological priorities of the state, making it a powerful tool for shaping political attitudes. In China, for example, textbooks emphasize national unity and the legitimacy of the Communist Party, while downplaying dissenting viewpoints. This approach ensures that students internalize a specific narrative about governance and civic duty. Conversely, in Scandinavian countries, curricula often focus on social equality and collective responsibility, reinforcing the values of their welfare states. The age at which these lessons are introduced is critical; research shows that political attitudes formed during adolescence tend to persist into adulthood, making the school years a pivotal period for political socialization.

However, the impact of schools on political knowledge and attitudes is not uniform. Variations in teaching methods, teacher biases, and student engagement can lead to divergent outcomes. For example, a teacher who encourages open debate and critical thinking may foster more politically engaged students, while a teacher who adheres strictly to the textbook may produce more passive learners. Additionally, extracurricular activities such as student councils or Model UN clubs can supplement formal education by providing practical experience in leadership and negotiation. Schools that integrate these activities into their programs often report higher levels of political participation among their graduates.

To maximize the positive impact of education on political socialization, policymakers and educators should consider several practical steps. First, curricula should be regularly updated to reflect contemporary political issues, ensuring relevance for students. Second, teacher training programs should emphasize the importance of impartiality and critical thinking, equipping educators to facilitate balanced discussions. Third, schools should encourage student participation in civic activities, such as voter registration drives or community service projects, to bridge the gap between theory and practice. By taking these steps, schools can play a more effective role in preparing students for active citizenship.

Despite its potential, the role of education in political socialization is not without challenges. Critics argue that schools can inadvertently reinforce political apathy if curricula are perceived as irrelevant or if teaching methods are uninspiring. Moreover, in diverse societies, balancing national narratives with the recognition of minority perspectives can be difficult. For example, in countries with a history of colonialism, indigenous students may feel alienated by curricula that prioritize the colonizer’s viewpoint. Addressing these challenges requires a commitment to inclusivity and a willingness to adapt educational practices to meet the needs of all students. Ultimately, the goal of political socialization through education should be to empower individuals to engage thoughtfully and critically with the political world, rather than simply conforming to existing norms.

Understanding Political Organizing: Strategies, Impact, and Community Engagement

You may want to see also

Media Impact: News, social media, and entertainment influence political perspectives

Media consumption shapes political perspectives in ways both subtle and profound. A 2021 Pew Research study found that 53% of Americans rely on news websites and apps as their primary source of political information. This constant exposure to curated narratives, whether from traditional outlets or digital platforms, molds how individuals interpret policies, candidates, and societal issues. For instance, a study published in *Political Communication* revealed that repeated exposure to partisan news increases polarization, with viewers adopting more extreme views aligned with their preferred outlet’s slant. This isn’t merely about facts; it’s about framing—how issues are presented, which voices are amplified, and which are silenced.

Social media amplifies this effect through algorithms designed to maximize engagement, often prioritizing sensational or divisive content. A 2020 report by the University of Oxford found that 87 countries used social media for political manipulation, leveraging bots, trolls, and targeted ads to sway public opinion. For younger demographics, this is particularly impactful: a survey by the Knight Foundation showed that 67% of 18- to 24-year-olds get their news from social media, where headlines and memes often replace in-depth analysis. This creates a feedback loop where users are fed content that reinforces their existing beliefs, fostering echo chambers and reducing exposure to opposing viewpoints.

Entertainment media, too, plays a stealthy role in political socialization. Television shows, films, and streaming content often embed political themes, normalizing certain ideologies or critiquing others. For example, *The West Wing* romanticized liberal democratic ideals, while *Law & Order* often portrayed law enforcement in a favorable light. A study in *Journal of Communication* found that viewers who frequently watched political dramas were more likely to engage in political discussions and develop stronger partisan identities. Even seemingly apolitical content can influence perceptions of authority, justice, and societal norms, subtly shaping how audiences interpret real-world politics.

To mitigate media’s influence, critical consumption is key. Start by diversifying your sources—include outlets from different ideological perspectives and fact-checking sites like PolitiFact or Snopes. Limit social media exposure by setting daily time limits (e.g., 30 minutes) and disabling notifications. Engage with content actively: ask who is speaking, why, and what might be omitted. For parents and educators, teaching media literacy to children as young as 8 can build resilience against manipulation. Tools like News Literacy Project’s *Checkology* offer resources to help young people discern credible information from misinformation.

Ultimately, media’s role in political socialization is a double-edged sword. While it democratizes access to information, it also risks distorting reality. By understanding its mechanisms and adopting mindful habits, individuals can harness its power without being swayed by its biases. The goal isn’t to avoid media but to engage with it intelligently, ensuring that it informs rather than manipulates.

Understanding Political Economic Context: Shaping Societies, Policies, and Global Dynamics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Peer Groups: Friends and social circles reinforce or challenge political views

Peer groups wield significant influence in shaping political beliefs, often acting as a secondary socialization force that either cements or disrupts the values instilled by family and early education. Consider the dynamics of a high school debate club: members, initially holding diverse viewpoints, gradually adopt shared political leanings through repeated exposure to each other’s arguments and the group’s dominant ideology. This phenomenon, known as "group polarization," illustrates how peer pressure and conformity can intensify political stances, turning moderate beliefs into more extreme positions. For instance, a study by the American Psychological Association found that adolescents who frequently discuss politics with friends are 30% more likely to adopt radicalized views compared to those who engage in such conversations less often.

To harness the positive potential of peer groups, intentional diversity within social circles is key. A practical strategy involves joining or forming discussion groups that intentionally include members from varying political backgrounds. For example, a college student might initiate a "Political Perspectives Café," where participants commit to respectful dialogue across party lines. This approach not only challenges individual biases but also fosters critical thinking by exposing members to alternative viewpoints. Research from the University of Michigan suggests that individuals who engage in cross-partisan discussions are 40% more likely to moderate their views and develop nuanced political beliefs.

However, the reinforcing power of homogeneous peer groups cannot be overlooked. Social media algorithms exacerbate this by creating echo chambers, where users are predominantly exposed to content that aligns with their existing beliefs. A 2021 Pew Research Center study revealed that 64% of social media users primarily follow accounts that share their political ideology, amplifying confirmation bias. To counteract this, individuals can actively seek out dissenting voices by following thought leaders from opposing parties or engaging with platforms that prioritize diverse content. For instance, using tools like "AllSides" to compare news coverage from different political perspectives can help break the cycle of reinforcement.

A cautionary note: while peer groups can be transformative, they can also lead to political alienation if not navigated thoughtfully. Adolescents, in particular, are vulnerable to adopting extreme views to gain social acceptance. Parents and educators can mitigate this risk by encouraging open dialogue about political differences and teaching media literacy skills. For example, a high school civics teacher might assign a project where students analyze political memes from multiple perspectives, fostering awareness of how peer influence shapes political consumption.

In conclusion, peer groups serve as both mirrors and windows in the process of political socialization. By understanding their dual role in reinforcing and challenging beliefs, individuals can strategically engage with their social circles to cultivate informed, adaptable political identities. Whether through diverse discussion groups, mindful social media use, or educational interventions, the key lies in leveraging peer dynamics to broaden rather than narrow one's political horizon.

Are Any Kennedys Still Shaping American Politics Today?

You may want to see also

Cultural Norms: Societal traditions and practices mold political identities and behaviors

Cultural norms, the unwritten rules that govern behavior within a society, are powerful forces in shaping political identities and actions. From birth, individuals are immersed in a web of traditions, rituals, and shared understandings that subtly, yet profoundly, influence their political outlook. Consider the annual Fourth of July celebrations in the United States. Beyond the fireworks and barbecues, these events reinforce national identity, patriotism, and a specific understanding of American values, all of which contribute to how individuals perceive their role in the political system.

This process of political socialization through cultural norms is not limited to grand national holidays. Everyday practices, like family dinner conversations, religious ceremonies, or even the stories we tell our children, all carry implicit political messages. A family that regularly discusses the importance of community service instills a sense of civic duty, potentially leading to higher voter turnout and engagement in local politics. Conversely, a community that emphasizes individualism might foster a more libertarian political outlook.

The power of cultural norms lies in their ability to operate on both conscious and subconscious levels. While some traditions explicitly promote certain political ideologies, others shape political behavior through implicit associations and emotional connections. For example, the tradition of respecting elders in many cultures often translates into a deference to authority figures, which can influence political attitudes towards leadership and governance.

Recognizing the role of cultural norms in political socialization is crucial for understanding political diversity and fostering informed citizenship. By examining the traditions and practices that surround us, we can become more aware of the subtle forces shaping our political identities. This awareness allows for a more critical evaluation of our beliefs and encourages a more nuanced understanding of the political beliefs of others.

Will Rogers' Witty Political Quotes: Timeless Humor and Insight

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political socialization is the process through which individuals acquire political values, beliefs, and behaviors, shaping their understanding of politics and their role within the political system.

Political socialization occurs through various agents such as family, schools, media, peers, and personal experiences, which collectively influence an individual’s political attitudes and orientations.

Political socialization begins in early childhood, often within the family, as children observe and internalize the political beliefs and behaviors of their parents or caregivers.

Yes, political socialization is not static; it can evolve due to life experiences, exposure to new ideas, education, and changing societal or political environments.

Political socialization is crucial as it helps maintain political stability, ensures the transmission of democratic values, and fosters civic engagement by shaping citizens’ participation in the political process.