Political sociology is a multidisciplinary field that examines the relationship between politics, power, and society, exploring how social structures, institutions, and inequalities shape political processes and outcomes. It investigates the interplay between the state, citizens, and various social groups, analyzing topics such as political participation, social movements, governance, and the distribution of resources. A PowerPoint presentation (PPT) on this subject would typically outline key concepts, theories, and methodologies, providing a comprehensive overview of how political sociology helps us understand the dynamics of power and authority within societal contexts. Such a presentation might also highlight real-world examples to illustrate the practical applications of political sociology in analyzing contemporary political issues.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Political Power Dynamics: Examines how power is distributed, exercised, and contested within societies

- State and Society Relations: Analyzes interactions between governments, institutions, and social groups

- Social Movements and Change: Studies collective actions driving political and societal transformations

- Ideology and Identity: Explores how beliefs, identities, and values shape political behavior

- Globalization and Politics: Investigates the impact of global processes on local and national politics

Political Power Dynamics: Examines how power is distributed, exercised, and contested within societies

Power is not merely held; it is performed, negotiated, and resisted. Political sociology dissects these dynamics by examining who wields power, how they maintain it, and the mechanisms through which it is challenged. Consider the corporate boardroom, where CEOs and shareholders exercise control over resources and decision-making. Their power is not just economic but also symbolic, reinforced by titles, access to networks, and the ability to shape narratives. Yet, this power is contested—by employees demanding better wages, by activists exposing unethical practices, and by regulatory bodies imposing constraints. This interplay reveals that power is not static; it is a fluid process shaped by constant negotiation and conflict.

To understand power distribution, one must map its sources and structures. Max Weber’s distinction between *coercive*, *legal-rational*, and *traditional* authority remains foundational. For instance, a dictator relies on coercive power, while a democratic leader derives authority from legal-rational systems. However, even in democracies, power is unevenly distributed. Wealth, gender, race, and education create hierarchies that influence political participation and outcomes. A practical tip for analyzing this: track campaign financing in elections. In the U.S., the top 0.01% of donors contribute over 40% of all campaign funds, illustrating how economic power translates into political influence. This disparity underscores the need to scrutinize not just formal institutions but also informal networks and resources that sustain power imbalances.

Contesting power requires strategic action, often through collective mobilization. Social movements, such as the Civil Rights Movement or #MeToo, exemplify how marginalized groups challenge dominant power structures. These movements employ tactics like protests, boycotts, and digital activism to disrupt the status quo. However, success is not guaranteed. Powerholders frequently respond with co-optation, repression, or token concessions. For instance, corporations may adopt superficial diversity policies to deflect criticism without addressing systemic inequalities. A cautionary note: while social media amplifies voices, it can also fragment movements, making sustained collective action more difficult. Effective resistance demands clear goals, organizational resilience, and alliances across diverse groups.

Finally, the exercise of power is deeply intertwined with ideology and discourse. Rulers do not just command; they persuade. Governments use rhetoric to legitimize policies, framing austerity measures as "necessary sacrifices" or military interventions as "humanitarian missions." Media plays a critical role here, either amplifying or challenging these narratives. A comparative analysis of news coverage during the Arab Spring versus the Occupy Movement reveals how framing can elevate or marginalize resistance efforts. To counter this, individuals must develop media literacy, questioning sources and seeking diverse perspectives. By deconstructing dominant narratives, one can expose the ideological underpinnings of power and open spaces for alternative visions of society.

In sum, political power dynamics are a complex web of distribution, exercise, and contestation. By analyzing structures, strategies, and ideologies, we gain tools to navigate and transform these dynamics. Whether through policy advocacy, grassroots organizing, or critical discourse analysis, understanding power is the first step toward reshaping it.

Is Fox News Politically Biased? Analyzing Its Editorial Stance and Impact

You may want to see also

State and Society Relations: Analyzes interactions between governments, institutions, and social groups

The relationship between the state and society is a dynamic interplay of power, influence, and negotiation. At its core, this relationship examines how governments, as representatives of the state, interact with various social groups and institutions, shaping policies, norms, and societal outcomes. This analysis is crucial for understanding the distribution of resources, the exercise of authority, and the mechanisms through which social change occurs.

Consider the role of interest groups in this interaction. These groups, ranging from labor unions to environmental organizations, act as intermediaries between the state and society. They mobilize resources, articulate demands, and negotiate with governments to influence policy outcomes. For instance, the success of the civil rights movement in the United States was not solely due to legislative action but also to the sustained pressure from grassroots organizations and their strategic engagement with state institutions. This example highlights how social groups can shape state behavior, demonstrating the reciprocal nature of state-society relations.

Analyzing these interactions requires a multi-faceted approach. One must examine the structural factors, such as the legal framework and economic policies, that enable or constrain societal participation. Equally important is the study of cultural norms and ideologies that legitimize state authority or foster resistance. For example, in authoritarian regimes, the state often employs censorship and propaganda to control narratives, while in democratic societies, free media and public discourse serve as checks on government power. Understanding these mechanisms provides insights into how power is contested and negotiated.

A practical takeaway from this analysis is the importance of fostering inclusive and transparent state-society interactions. Governments can enhance legitimacy and effectiveness by creating avenues for meaningful participation, such as public consultations, participatory budgeting, and responsive governance mechanisms. Conversely, social groups must develop strategies that leverage their collective strength, such as coalition-building and evidence-based advocacy, to influence policy. For instance, the global climate movement has gained traction by combining local activism with international advocacy, pressuring governments to adopt more ambitious environmental policies.

In conclusion, the study of state and society relations offers a lens to decipher the complexities of political and social life. By examining the interactions between governments, institutions, and social groups, we can identify patterns of power, understand the drivers of social change, and devise strategies for more equitable and democratic societies. This analysis is not merely academic but has practical implications for policymakers, activists, and citizens seeking to navigate and shape the political landscape.

Do You Like Politics? Exploring the Love-Hate Relationship with Governance

You may want to see also

Social Movements and Change: Studies collective actions driving political and societal transformations

Social movements are the engines of political and societal change, often emerging from collective discontent and mobilizing diverse groups toward shared goals. Consider the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, which employed nonviolent protests, boycotts, and legal challenges to dismantle racial segregation. This movement not only transformed laws but also reshaped cultural norms, demonstrating how collective action can challenge entrenched power structures. Analyzing such movements reveals a pattern: they thrive on grassroots organization, strategic framing of grievances, and the ability to sustain momentum despite repression. For instance, the use of mass media and symbolic actions, like the Montgomery Bus Boycott, amplified the movement’s message, illustrating the power of visibility in driving change.

To study social movements effectively, researchers must adopt a multi-faceted approach. Begin by identifying the movement’s core demands and the socio-political context in which it arises. For example, the #MeToo movement emerged in response to systemic gender-based violence, leveraging social media to create a global conversation. Next, examine the tactics employed—whether direct action, lobbying, or cultural production—and their impact on policy and public opinion. Caution: avoid reducing movements to their outcomes; many achieve long-term cultural shifts even if immediate policy goals are unmet. Finally, consider the role of leadership versus decentralized organizing. Movements like Black Lives Matter, with its leaderful model, show how distributed authority can foster resilience and inclusivity.

Persuasive arguments for the importance of social movements often highlight their role in democratizing societies. Movements push governments to address inequalities and hold institutions accountable. For instance, the Arab Spring uprisings, though varied in outcome, underscored the universal desire for political freedom and economic justice. However, critics argue that movements can fragment or lose focus without clear structures. To counter this, successful movements often develop coalitions, as seen in the environmental justice movement, which unites diverse groups around shared ecological concerns. Practical tip: when engaging in or studying movements, prioritize intersectionality to ensure marginalized voices are not overlooked.

Comparing social movements across time and geography reveals both commonalities and unique challenges. The anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, for instance, combined international solidarity campaigns with internal resistance, showcasing the importance of global networks. In contrast, contemporary movements like Extinction Rebellion use civil disobedience to demand urgent climate action, reflecting the urgency of modern crises. A key takeaway is that while contexts differ, the principles of solidarity, adaptability, and strategic communication remain vital. For those seeking to initiate or support a movement, start by mapping existing resources, building alliances, and crafting a narrative that resonates broadly.

Descriptively, social movements are living laboratories of democracy, testing new forms of participation and governance. Occupy Wall Street, for example, experimented with consensus-based decision-making, offering a critique of hierarchical systems. Similarly, the Indigenous rights movement in Latin America has revived traditional governance models, challenging Western notions of statehood. These examples underscore the transformative potential of movements beyond policy change—they reimagine societal structures. To engage meaningfully, individuals can participate in local initiatives, amplify movement voices through social media, or contribute to research documenting their impact. Ultimately, social movements remind us that change is not inevitable but a product of collective effort and vision.

Gracefully Canceling Interviews: Professional Tips for Polite Declination

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Ideology and Identity: Explores how beliefs, identities, and values shape political behavior

Political behavior is not a random act but a reflection of deeply ingrained ideologies and identities. These elements—beliefs, values, and self-perceptions—act as lenses through which individuals interpret political events, form opinions, and take action. For instance, someone who identifies strongly with a nationalist ideology is more likely to support policies prioritizing national interests over global cooperation. Conversely, an individual rooted in egalitarian values may advocate for redistributive policies to address economic inequality. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for predicting voter behavior, policy preferences, and even social movements.

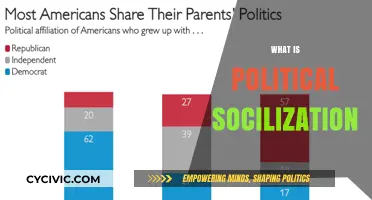

Consider the role of identity in shaping political engagement. Racial, ethnic, or religious identities often align with specific political parties or causes. In the United States, African American voters historically lean Democratic due to the party’s alignment with civil rights issues. Similarly, in India, caste identity significantly influences voting patterns, with marginalized groups often supporting parties promising affirmative action. This alignment is not coincidental but a result of shared values and perceived representation. To analyze this, sociologists use tools like survey data and qualitative interviews to map how identities correlate with political choices.

However, ideologies and identities are not static; they evolve in response to societal changes. For example, the rise of environmentalism as a political ideology reflects growing concerns about climate change. Younger generations, particularly those under 30, are more likely to prioritize green policies, often integrating environmentalism into their personal identities. This shift challenges traditional political divides, forcing parties to adapt their platforms. Practitioners in political sociology must track these trends to understand emerging voter blocs and their demands.

A practical takeaway for policymakers and activists is the importance of framing issues in ways that resonate with target audiences’ identities and values. For instance, advocating for healthcare reform as a matter of economic efficiency might appeal to fiscal conservatives, while framing it as a human rights issue could mobilize progressives. Tailoring messages to align with specific ideologies increases their effectiveness. A caution, though: over-reliance on identity-based appeals can deepen political polarization, as seen in campaigns that exploit cultural divisions for electoral gain.

In conclusion, ideology and identity are not mere background factors but active forces driving political behavior. By examining how beliefs and self-perceptions intersect with political choices, sociologists uncover patterns that explain both individual actions and broader societal trends. For anyone seeking to influence political outcomes—whether through policy, activism, or research—grasping this interplay is essential. It’s not just about understanding what people think, but why they think it and how it shapes their actions.

Understanding Political Interest Groups: Power, Influence, and Advocacy Explained

You may want to see also

Globalization and Politics: Investigates the impact of global processes on local and national politics

Globalization has reshaped the boundaries of political influence, making local and national politics increasingly susceptible to global forces. Transnational corporations, for instance, wield economic power that can rival or surpass that of nation-states, influencing policies on taxation, labor rights, and environmental regulations. Consider the case of Ireland, where Apple’s tax arrangements became a focal point of EU scrutiny, highlighting how global corporate strategies can dictate national fiscal policies. This example underscores the erosion of state sovereignty in the face of global economic integration.

Analyzing the impact of globalization on politics requires examining its dual nature: as both a unifier and a divider. On one hand, global institutions like the United Nations and the World Trade Organization foster cooperation, setting norms and standards that transcend borders. On the other hand, globalization exacerbates inequalities, as seen in the backlash against trade agreements like NAFTA, which critics argue disproportionately benefit wealthier nations. This duality reveals how global processes can simultaneously empower and marginalize, depending on the context and the actors involved.

To understand globalization’s political implications, consider its role in reshaping identity politics. Global migration patterns, driven by economic disparities and conflict, have led to multicultural societies that challenge traditional notions of national identity. In countries like Germany, the influx of refugees has sparked debates over integration, security, and cultural preservation, illustrating how global movements of people can become central to local political discourse. Policymakers must navigate these tensions, balancing global humanitarian obligations with domestic political pressures.

A practical takeaway for policymakers is the need to adopt a multi-scalar approach to governance. This involves recognizing that political decisions are no longer confined to national borders and require coordination across local, national, and global levels. For example, climate change policies must align with international agreements like the Paris Accord while addressing regional and local concerns. Failure to integrate these scales can lead to policy incoherence, as seen in the U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Accord under the Trump administration, which created a disconnect between global commitments and national actions.

Finally, the study of globalization and politics demands a critical lens on power dynamics. Global processes are not neutral; they are shaped by dominant actors, often from the Global North, who set the agenda for trade, security, and development. Developing nations, meanwhile, often find themselves at a disadvantage, with limited influence over decisions that profoundly affect their economies and societies. To address this imbalance, scholars and practitioners must advocate for more inclusive global governance structures that amplify the voices of marginalized states and communities. This shift is essential for ensuring that globalization serves as a force for equitable progress rather than perpetuating existing inequalities.

Jack's Political Allegories: Decoding Power, Corruption, and Society in His Works

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political sociology in a PPT (PowerPoint) context refers to a presentation format used to explain the interdisciplinary study of power, politics, and society. It typically covers topics like the relationship between state, institutions, and social structures, often with visual aids for clarity.

A political sociology PPT often includes topics such as the role of the state, political power and inequality, social movements, political participation, and the interplay between politics and social class, race, and gender.

A political sociology PPT is commonly used in academic settings as a teaching tool to introduce complex concepts, illustrate theories, and summarize research findings. It helps students visualize relationships between politics and society.

Using a PPT for political sociology allows for concise, organized, and visually engaging explanations. It simplifies complex ideas, highlights key points, and can incorporate graphs, charts, and images to enhance understanding.