Political socialization is the process through which individuals acquire political values, beliefs, and behaviors, shaping their understanding of and engagement with the political world. It begins in childhood and continues throughout life, influenced by various agents such as family, education, media, peers, and personal experiences. These agents transmit norms, ideologies, and attitudes about government, citizenship, and societal issues, molding how individuals perceive political systems and their role within them. Understanding political socialization is crucial for comprehending why people hold certain political views, participate in political activities, or align with specific parties or movements, as it highlights the interplay between personal development and broader societal and cultural contexts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The process by which individuals acquire political beliefs, values, and behaviors. |

| Agents of Socialization | Family, education system, media, peers, religious institutions, and government. |

| Lifelong Process | Continues throughout life, though most intense during childhood and adolescence. |

| Cultural Influence | Shaped by cultural norms, traditions, and historical context of a society. |

| Political Participation | Influences attitudes toward voting, activism, and engagement in politics. |

| Ideological Formation | Shapes political ideologies (e.g., liberalism, conservatism, socialism). |

| Normalization of Power Structures | Reinforces acceptance of existing political systems and authority figures. |

| Critical Thinking Development | Can either encourage or discourage questioning of political norms and systems. |

| Globalization Impact | Increasingly influenced by global media, international events, and cross-cultural interactions. |

| Digital Age Influence | Social media and online platforms play a significant role in shaping political views. |

| Resistance and Counter-Socialization | Individuals or groups may challenge dominant political narratives and create alternative beliefs. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Family Influence: Parents, siblings, and relatives shape early political beliefs and attitudes

- Education Role: Schools and curricula instill civic values, norms, and political knowledge

- Media Impact: News, social media, and entertainment influence political perceptions and opinions

- Peer Groups: Friends and social circles reinforce or challenge political ideologies

- Cultural Factors: Traditions, religion, and societal norms contribute to political socialization

Family Influence: Parents, siblings, and relatives shape early political beliefs and attitudes

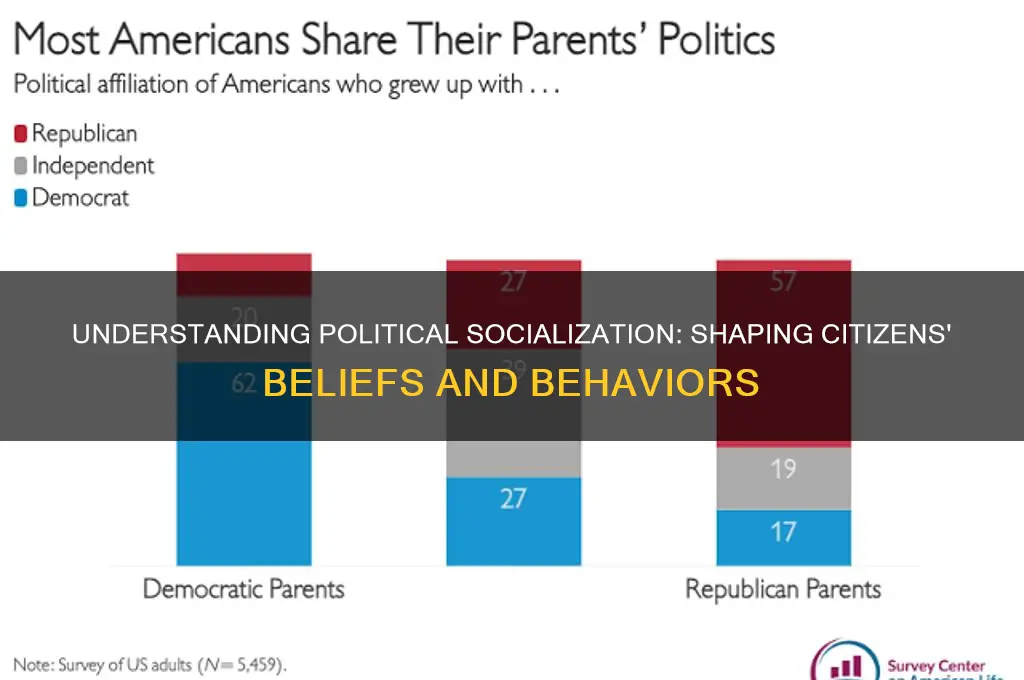

The family dinner table is often the first political arena a child encounters. Conversations about current events, government policies, or even local community issues introduce children to the world of politics long before they step into a classroom. Parents, as primary caregivers and role models, play a pivotal role in shaping their children's political beliefs and attitudes. A study by the Pew Research Center found that 70% of adults report their parents’ political views influenced their own, highlighting the enduring impact of familial political discourse.

Consider the mechanics of this influence. Parents not only express their political opinions but also model behaviors such as voting, engaging in political discussions, or participating in community activities. For instance, a child who accompanies their parents to a polling station or sees them volunteering for a political campaign is more likely to perceive civic engagement as a norm. Siblings and relatives further amplify this effect by introducing diverse perspectives or reinforcing shared beliefs. A younger sibling might adopt the political leanings of an older sibling they admire, while a politically active grandparent could spark curiosity through storytelling or debate.

However, family influence is not uniform. The age at which children are exposed to political discussions matters. Research suggests that children as young as 5 begin forming rudimentary political identities, often mirroring their parents’ views. By adolescence, these beliefs may evolve as teens encounter external influences, but the foundational attitudes remain rooted in early familial experiences. For example, a child raised in a household that emphasizes social justice is more likely to prioritize progressive policies in adulthood, even if they later diverge from their family’s specific party affiliation.

To maximize positive family influence, parents and relatives can adopt practical strategies. First, encourage open dialogue rather than monologue. Allow children to ask questions and express their thoughts without fear of judgment. Second, expose them to a variety of political perspectives, even if they contradict your own. This fosters critical thinking and tolerance. Finally, model constructive political engagement by avoiding divisive language and focusing on solutions rather than blame. For instance, instead of labeling a political opponent as "wrong," discuss the underlying reasons for differing viewpoints.

In conclusion, the family unit serves as a powerful incubator for political socialization. By understanding the mechanisms and timing of this influence, parents and relatives can shape not only their children’s political beliefs but also their approach to civic participation. The dinner table conversations of today lay the groundwork for the voting booths and community halls of tomorrow.

Unraveling the Political Underpinnings of the COVID-19 Pandemic

You may want to see also

Education Role: Schools and curricula instill civic values, norms, and political knowledge

Schools serve as primary agents of political socialization, systematically embedding civic values, norms, and political knowledge into students' minds. From the Pledge of Allegiance recited daily in American classrooms to the compulsory citizenship education in Finnish schools, curricula worldwide are designed to shape young citizens. In the United States, for instance, the No Child Left Behind Act mandates that schools receiving federal funding must teach civics, ensuring a baseline of political literacy. This structured approach ensures that students not only learn about democratic principles but also internalize them through repetition and practice.

Consider the role of textbooks, which often reflect a nation's political ideology. In India, history textbooks emphasize unity in diversity, reinforcing the country's secular and democratic ethos. Conversely, in authoritarian regimes, textbooks may glorify the ruling party or omit dissenting viewpoints. This highlights the power of curricula to either foster critical thinking or perpetuate compliance. Educators must therefore balance imparting foundational knowledge with encouraging students to question and analyze political systems.

Practical integration of civic education can take many forms. For younger students (ages 8–12), role-playing activities like mock elections or classroom debates introduce democratic processes in an engaging way. High school students (ages 14–18) benefit from more complex exercises, such as policy analysis or community service projects, which connect abstract concepts to real-world issues. For example, a project on local zoning laws can teach students about governance while empowering them to advocate for change in their neighborhoods.

However, the effectiveness of schools in political socialization depends on teacher training and resource allocation. A 2018 study by the Annenberg Public Policy Center found that only 24% of U.S. teachers felt "very well prepared" to teach civics. Addressing this gap requires investing in professional development programs that equip educators with both content knowledge and pedagogical strategies. Schools should also collaborate with community organizations to provide students with hands-on experiences, such as internships in local government offices or participation in youth councils.

Ultimately, the education system's role in political socialization is both a privilege and a responsibility. By thoughtfully designing curricula and supporting educators, schools can cultivate informed, engaged citizens capable of navigating complex political landscapes. Yet, this process must remain dynamic, adapting to societal changes and encouraging students to think critically rather than passively absorb information. In doing so, education becomes not just a tool for socialization but a catalyst for democratic renewal.

Understanding Political Organizations: Structure, Roles, and Influence in Society

You may want to see also

Media Impact: News, social media, and entertainment influence political perceptions and opinions

Media shapes political perceptions through a constant drip of narratives, framing issues in ways that subtly—or not so subtly—guide public opinion. News outlets, for instance, often prioritize sensationalism over nuance, amplifying extreme viewpoints to capture attention. A study by the Pew Research Center found that 57% of Americans believe news organizations favor one political side over another, illustrating how media bias influences audience trust and interpretation. When a network repeatedly labels a policy as "radical" or "dangerous," viewers internalize that framing, even if the policy’s details are never fully explained. This isn’t just about slant; it’s about the structure of storytelling, where conflict and drama dominate, leaving little room for balanced analysis.

Social media accelerates this process, turning political discourse into a rapid-fire exchange of memes, soundbites, and outrage. Algorithms reward engagement, pushing content that sparks strong emotional reactions—often anger or fear. For example, a 2020 study published in *Nature* found that false political news spreads six times faster than factual information on Twitter. This isn’t accidental; platforms are designed to keep users scrolling, and polarizing content is highly effective at achieving that goal. A teenager scrolling through TikTok might encounter a 15-second clip criticizing a politician’s stance on climate change, paired with dramatic music and stark visuals. Without context or counterarguments, that clip becomes their entire understanding of the issue.

Entertainment media, meanwhile, embeds political messages in seemingly apolitical content, normalizing certain ideologies through characters, plots, and cultural references. Sitcoms, dramas, and even superhero movies often reflect the creators’ values, whether intentionally or not. For instance, shows like *The West Wing* romanticize idealistic politics, while dystopian series like *The Handmaid’s Tale* warn of authoritarianism. These narratives don’t just entertain; they shape how viewers perceive real-world politics. A 2018 survey by the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative revealed that 44% of respondents reported changing their views on social issues after watching a TV show or film. This underscores how entertainment can act as a Trojan horse for political socialization, influencing opinions without viewers even realizing it.

To mitigate media’s influence, critical consumption is key. Start by diversifying your sources: follow outlets with differing perspectives, and fact-check claims using nonpartisan organizations like PolitiFact or Snopes. On social media, adjust your settings to reduce algorithmic bias—for example, Instagram allows users to snooze political content or limit time spent on the app. For entertainment, engage in media literacy practices: discuss shows with others to unpack hidden messages, and seek out diverse genres and creators. Parents can guide younger audiences by co-viewing content and asking questions like, “What’s missing from this story?” or “Who benefits from this portrayal?” By actively questioning media, individuals can reclaim their role as informed consumers rather than passive recipients of political narratives.

Is Vijay's Political Entry Imminent? Analyzing the Actor's Political Ambitions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Peer Groups: Friends and social circles reinforce or challenge political ideologies

Peer groups wield significant influence in shaping political beliefs, often serving as a crucible where ideologies are forged, tested, and sometimes transformed. During adolescence and early adulthood, when individuals are most impressionable, friends and social circles become secondary agents of political socialization, complementing or contradicting lessons from family and formal education. A study by the Pew Research Center found that 58% of millennials report discussing politics with friends at least once a month, highlighting the frequency and intensity of these interactions. These conversations, whether casual debates or passionate arguments, subtly embed political norms and values, often reinforcing shared beliefs within the group.

Consider the mechanics of this process: peer groups operate through social validation and conformity. When a friend expresses a political stance, others are more likely to adopt or at least consider it to maintain group cohesion. For instance, a teenager in a socially conscious friend group might embrace progressive policies like climate action or social justice, not solely out of personal conviction but to align with the collective identity. Conversely, dissenting voices within the group can challenge these norms, fostering critical thinking. A 2018 study published in *Political Psychology* revealed that exposure to diverse viewpoints within peer networks increases political tolerance and reduces ideological rigidity, particularly among 18- to 25-year-olds.

However, the impact of peer groups isn’t uniform. Socioeconomic status, geographic location, and cultural background shape the composition of these circles, dictating the range of political ideas encountered. For example, a student in a homogeneous suburban community may encounter fewer dissenting opinions compared to one in a diverse urban setting. Practical strategies to maximize the positive influence of peer groups include intentionally seeking out diverse social circles and encouraging open dialogue. Parents and educators can facilitate this by organizing cross-community events or debates, exposing young adults to perspectives beyond their immediate environment.

The digital age amplifies the role of peer groups in political socialization. Social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok have become virtual town squares where political ideas are shared, debated, and amplified. A 2021 survey by the Knight Foundation found that 63% of Gen Z and millennials report learning about current events through social media, often influenced by peers’ posts or stories. While this can create echo chambers, it also offers opportunities for exposure to global issues and grassroots movements. To navigate this landscape, individuals should critically evaluate online content, verify sources, and engage with accounts that challenge their worldview.

In conclusion, peer groups are dynamic arenas where political ideologies are reinforced, contested, and refined. By understanding their mechanisms and leveraging their potential, individuals can cultivate a more informed and resilient political identity. Whether through face-to-face conversations or digital interactions, the influence of friends and social circles is undeniable—a force that, when harnessed thoughtfully, can foster both personal growth and civic engagement.

Jimmies: A Politically Incorrect Term or Harmless Slang?

You may want to see also

Cultural Factors: Traditions, religion, and societal norms contribute to political socialization

Cultural transmission of political values often begins with traditions, which serve as unspoken curricula for civic behavior. Consider the annual Bastille Day celebrations in France, where reenactments, parades, and public speeches reinforce the nation’s revolutionary heritage and commitment to liberty. These rituals are not mere entertainment; they subtly teach citizens about the importance of resistance to tyranny and the value of democratic ideals. Similarly, in the United States, Thanksgiving’s historical narrative, though contested, often emphasizes themes of unity and compromise, indirectly shaping attitudes toward governance and collective responsibility. Such traditions act as cultural glue, binding individuals to shared political identities and norms.

Religion, another cornerstone of cultural influence, provides moral frameworks that intersect with political beliefs. In predominantly Catholic countries like Poland, the Church’s teachings on social justice and solidarity have historically shaped labor movements and resistance to authoritarianism. Conversely, in secular societies like Sweden, the absence of religious dominance has fostered a strong emphasis on state-led welfare policies, reflecting a collective trust in government as a moral authority. Religious institutions often act as intermediaries between the individual and the state, interpreting political issues through a spiritual lens and guiding followers’ stances on topics like abortion, marriage equality, or economic redistribution.

Societal norms, though less overt than traditions or religion, exert profound pressure on political attitudes. In Japan, the cultural emphasis on harmony (*wa*) discourages public dissent, leading to a political landscape where consensus-building is prioritized over confrontation. This norm influences not only voter behavior but also the structure of political parties, which often avoid divisive rhetoric. Conversely, in India, the caste system, though legally abolished, continues to shape political alliances and voter preferences, demonstrating how deeply ingrained social hierarchies can perpetuate or challenge political inequalities.

To harness cultural factors for positive political socialization, educators and policymakers must engage critically with these influences. For instance, integrating diverse cultural narratives into civic education can counter monolithic interpretations of history. In South Africa, post-apartheid curricula include both the struggles of the anti-apartheid movement and the complexities of reconciliation, fostering a nuanced understanding of democracy. Similarly, encouraging interfaith dialogues can bridge religious divides, as seen in initiatives like the *A Common Word* project, which promotes cooperation between Muslims and Christians on global issues.

Ultimately, cultural factors are not deterministic but dynamic, offering both opportunities and challenges for political socialization. By recognizing their role, societies can cultivate a more inclusive and informed citizenry. For parents and educators, this means actively questioning inherited norms and encouraging dialogue across cultural lines. For policymakers, it involves designing institutions that respect cultural diversity while upholding universal democratic principles. The goal is not to erase cultural differences but to ensure they enrich, rather than hinder, the political fabric.

Navigating the Noise: Strategies to Ignore Political Bullshit Effectively

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political socialization is the process through which individuals acquire political values, beliefs, and behaviors, shaping their understanding of politics and their role in the political system.

The main agents of political socialization include family, schools, peers, media, and religious institutions, which collectively influence an individual’s political attitudes and orientations.

Political socialization influences political participation by instilling norms, attitudes, and skills that encourage or discourage engagement in activities like voting, activism, or joining political organizations.