Political science is the systematic study of politics, power, and governance, examining how societies organize themselves, make decisions, and manage conflicts. It explores the structures, processes, and behaviors of governments, institutions, and individuals within political systems, both historically and in contemporary contexts. By analyzing topics such as political theory, comparative politics, international relations, public policy, and political behavior, political science seeks to understand the dynamics of authority, the distribution of resources, and the interplay between states and citizens. It is both an empirical and normative discipline, combining research methods from the social sciences with philosophical inquiries into justice, democracy, and the ideal functioning of political systems. As a field, political science plays a critical role in shaping public discourse, informing policy-making, and fostering a deeper understanding of the complex forces that shape our world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The systematic study of governance, power, and political behavior. |

| Scope | Encompasses institutions, policies, ideologies, and political processes. |

| Key Focus | Power dynamics, decision-making, and resource distribution. |

| Methodologies | Quantitative (statistics, surveys) and qualitative (case studies, interviews). |

| Subfields | Comparative politics, international relations, political theory, public policy, etc. |

| Theoretical Approaches | Realism, liberalism, constructivism, Marxism, feminism, etc. |

| Practical Applications | Policy analysis, political consulting, diplomacy, public administration. |

| Historical Perspective | Rooted in ancient philosophy (Plato, Aristotle) and modern political thought. |

| Interdisciplinary Links | Economics, sociology, psychology, law, and history. |

| Global Relevance | Studies political systems across nations, including democracies, autocracies, and hybrid regimes. |

| Current Trends | Focus on globalization, climate politics, digital governance, and populism. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Political Theory: Study of ideas, principles, and concepts shaping political systems and governance

- Comparative Politics: Analysis of political systems, institutions, and processes across different countries

- International Relations: Examination of interactions, conflicts, and cooperation between nations and global actors

- Political Economy: Intersection of politics and economics, focusing on power, resources, and policy

- Public Policy: Formulation, implementation, and evaluation of government policies to address societal issues

Political Theory: Study of ideas, principles, and concepts shaping political systems and governance

Political theory is the intellectual backbone of political science, delving into the ideas, principles, and concepts that underpin how societies govern themselves. It asks fundamental questions: What is justice? How should power be distributed? What constitutes legitimate authority? These inquiries are not abstract; they shape real-world systems, from democratic constitutions to authoritarian regimes. For instance, John Locke’s theory of social contract, which posits that governments derive their power from the consent of the governed, directly influenced the American and French Revolutions. Understanding such theories is essential for deciphering the origins and evolution of political institutions.

To study political theory effectively, begin by examining classical texts like Plato’s *Republic* or Rousseau’s *The Social Contract*. These works introduce foundational concepts such as the ideal state, the general will, and the role of the individual in society. Pair this with contemporary analyses to see how these ideas adapt to modern challenges, such as globalization or digital governance. For example, while Rousseau argued for direct democracy, modern theorists like Robert Dahl propose polyarchy, a system of pluralistic competition, to address the impracticalities of large-scale direct participation. This comparative approach reveals both the enduring relevance and limitations of historical theories.

A practical exercise in political theory involves applying its principles to current issues. Take the concept of equality, a central theme in theories from Marx to Rawls. Marx’s critique of capitalism as inherently unequal contrasts with Rawls’s theory of justice as fairness, which allows for inequalities if they benefit the least advantaged. To test these ideas, analyze a policy like universal basic income (UBI). Does UBI align with Marx’s vision of a classless society, or does it better fit Rawls’s framework by providing a social minimum? Such exercises bridge theory and practice, sharpening analytical skills and fostering critical thinking.

Caution must be exercised when interpreting political theory, as its abstract nature can lead to oversimplification. For instance, Machiavelli’s *The Prince* is often reduced to a manual for ruthless leadership, ignoring its nuanced exploration of political realism. Similarly, feminism in political theory is not a monolithic doctrine but a diverse field addressing intersectionality, power structures, and representation. Always contextualize theories within their historical and cultural settings to avoid misapplication. For example, applying Hobbes’s absolutist views to a modern democracy would overlook the intervening development of human rights and constitutionalism.

In conclusion, political theory is not merely an academic exercise but a toolkit for understanding and shaping governance. By engaging with its ideas, principles, and concepts, one gains insight into the forces that mold political systems. Whether dissecting classical texts, applying theories to contemporary issues, or navigating their complexities, the study of political theory equips individuals to critically evaluate the world and envision alternatives. It is a discipline that demands rigor, curiosity, and a willingness to question the status quo.

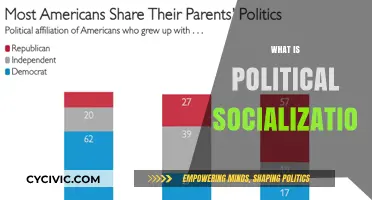

Family Politics: How Values Shape Relationships and Influence Generations

You may want to see also

Comparative Politics: Analysis of political systems, institutions, and processes across different countries

Political systems, from the parliamentary democracy of the United Kingdom to the presidential system of the United States, exhibit stark differences in structure, function, and outcomes. Comparative politics seeks to unravel these complexities by examining how institutions like legislatures, judiciaries, and executives operate in diverse contexts. For instance, while the UK’s Parliament holds supreme legislative power, the U.S. Congress shares authority with an independent judiciary and a powerful executive. Such comparisons reveal not only the mechanics of governance but also the historical, cultural, and socioeconomic factors that shape them. By analyzing these systems, scholars identify patterns, such as the correlation between proportional representation and multi-party systems, or the impact of federalism on regional autonomy.

To conduct a comparative analysis, researchers employ methodologies ranging from qualitative case studies to quantitative cross-national datasets. A common approach is the "most similar systems design," where countries with shared traits (e.g., Germany and Austria) are compared to isolate the effects of specific variables, such as electoral rules. For example, studying why Germany’s mixed-member proportional system produces coalition governments while France’s two-round system favors majoritarian outcomes provides insights into the role of electoral institutions in shaping party systems. Caution must be exercised, however, to avoid oversimplification; factors like historical legacies and economic disparities often complicate direct comparisons. Practical tips for researchers include triangulating data sources and incorporating local expertise to ensure nuanced interpretations.

Persuasive arguments in comparative politics often center on the normative implications of different political systems. Advocates of parliamentary democracies, for instance, highlight their ability to foster consensus-building, as seen in Scandinavian countries with high levels of social welfare and political stability. Critics, however, point to the potential for weak minority representation in majoritarian systems. Similarly, debates over presidentialism versus parliamentarism often hinge on questions of accountability and efficiency. A persuasive analysis might argue that while presidential systems provide clear lines of authority, they risk gridlock, as evidenced by frequent legislative stalemates in the U.S. Such arguments underscore the importance of context in evaluating the merits of political institutions.

Descriptively, comparative politics offers a rich tapestry of institutional diversity. Consider the contrast between the highly centralized state of China and the decentralized federalism of India. China’s single-party system prioritizes policy implementation and long-term planning, while India’s multi-party democracy emphasizes local representation and coalition-building. These differences are not merely structural but reflect deeper philosophical divides about the role of the state and the individual. By describing such variations, comparative politics provides a foundation for understanding global political dynamics, from the rise of populism in Europe to the resilience of authoritarian regimes in the Middle East. Practical takeaways include the recognition that no single system is universally superior; effectiveness depends on alignment with local conditions and values.

In conclusion, comparative politics serves as a critical tool for deciphering the complexities of global governance. By systematically analyzing political systems, institutions, and processes across countries, it offers both empirical insights and normative lessons. Whether through methodological rigor, persuasive argumentation, or descriptive richness, this subfield equips scholars and practitioners with the knowledge to navigate an increasingly interconnected world. For those seeking to understand why some democracies thrive while others falter, or how authoritarian regimes maintain control, comparative politics provides a roadmap—one that balances analytical precision with an appreciation for the unique contexts that shape political life.

Understanding Political Grievances: Causes, Impacts, and Resolution Strategies

You may want to see also

International Relations: Examination of interactions, conflicts, and cooperation between nations and global actors

Nations, like individuals, have interests, ambitions, and fears that drive their behavior on the global stage. International Relations (IR) is the lens through which we examine these complex dynamics, dissecting the intricate web of interactions, conflicts, and cooperation between states and other global actors. It's a field that demands a nuanced understanding of history, culture, economics, and power structures, as these factors shape the decisions and actions of nations.

For instance, consider the ongoing tensions between China and the United States. This rivalry is not merely a clash of personalities or ideologies, but a multifaceted struggle for economic dominance, technological supremacy, and geopolitical influence. IR scholars would analyze this conflict through various theoretical frameworks, such as realism, which emphasizes the anarchic nature of the international system and the pursuit of power, or liberalism, which highlights the role of institutions, norms, and cooperation in mitigating conflicts.

To grasp the intricacies of IR, one must delve into the various levels of analysis. At the systemic level, we examine the global distribution of power, the role of international institutions like the United Nations, and the impact of globalization on state behavior. Moving to the state level, we explore the domestic factors that shape foreign policy, such as political systems, economic interests, and public opinion. Finally, at the individual level, we consider the role of leaders, diplomats, and other decision-makers in shaping international outcomes. A comprehensive understanding of IR requires integrating these levels of analysis, recognizing that international relations are not solely driven by abstract forces, but by the actions and decisions of human actors.

Effective diplomacy is crucial in navigating the complex landscape of international relations. It involves a delicate balance of negotiation, persuasion, and compromise, often requiring creative solutions to seemingly intractable problems. For example, the 2015 Iran Nuclear Deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), was a landmark agreement that limited Iran's nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief. This deal was the culmination of years of intense negotiations, involving multiple stakeholders with competing interests. The JCPOA demonstrates the potential for diplomacy to achieve tangible results, even in the face of deep-seated mistrust and historical animosities. However, it also highlights the fragility of such agreements, as the deal's future remains uncertain in the face of shifting political landscapes and competing geopolitical interests.

As we navigate an increasingly interconnected and interdependent world, the study of International Relations becomes ever more critical. From climate change to global health crises, from economic inequality to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, the challenges we face demand collective action and cooperation. IR provides a framework for understanding these complex issues, offering insights into the motivations and behaviors of states and other global actors. By examining the interactions, conflicts, and cooperation between nations, we can develop more effective strategies for addressing global challenges, promoting peace, and fostering a more just and equitable international order. This requires a commitment to ongoing learning, critical thinking, and engagement with diverse perspectives, as we strive to build a more sustainable and prosperous future for all.

Understanding Global Power Dynamics: How World Politics Shapes Our Future

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.53 $16.99

Political Economy: Intersection of politics and economics, focusing on power, resources, and policy

Political economy is the study of how political forces shape economic outcomes and vice versa. At its core, it examines the interplay between power, resources, and policy, revealing how decisions about wealth distribution, market regulation, and public spending are fundamentally political acts. For instance, consider the global response to the 2008 financial crisis: governments bailed out banks while austerity measures shifted the burden onto citizens, illustrating how political choices prioritize certain economic interests over others. This dynamic underscores the inextricable link between who holds power and how resources are allocated.

To understand political economy, start by mapping the power structures within a given system. Identify key actors—governments, corporations, international institutions—and their influence over economic policies. For example, lobbying by tech giants often shapes antitrust legislation, demonstrating how corporate power can distort market competition. Analyzing these relationships requires a critical lens, as power is rarely transparent. Tools like policy tracing, where you follow the origins and impacts of a specific law, can reveal hidden agendas and unintended consequences.

A persuasive argument for studying political economy lies in its ability to explain inequality. Economic disparities are not natural outcomes but results of political decisions, such as tax policies favoring the wealthy or trade agreements undermining local industries. Take the case of developing nations burdened by debt: structural adjustment programs imposed by the IMF often prioritize debt repayment over social spending, exacerbating poverty. By exposing these mechanisms, political economy empowers advocates to challenge inequitable systems and propose alternatives.

Comparatively, political economy differs from traditional economics by rejecting the assumption of a neutral, apolitical market. While economics focuses on efficiency and equilibrium, political economy asks who benefits from these outcomes. For instance, free trade agreements are often touted as win-win solutions, but political economy reveals how they can disadvantage weaker economies. This comparative approach highlights the importance of context: what works in one political system may fail in another due to differing power dynamics.

In practice, applying political economy requires a multi-step approach. First, identify the resource in question—land, labor, capital—and trace its distribution. Second, analyze the policies governing that resource, such as land reform laws or labor regulations. Third, assess the power structures influencing these policies, including interest groups and international pressures. Finally, evaluate the outcomes for different stakeholders. For example, a study of water privatization in Bolivia shows how policy decisions led to price hikes, sparking protests and ultimately reversing the policy. This methodical approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of the political-economic landscape.

In conclusion, political economy serves as a lens for deciphering the complex relationship between politics and economics. By focusing on power, resources, and policy, it provides actionable insights into how societies allocate wealth and opportunity. Whether analyzing global trade, local taxation, or corporate influence, this framework equips individuals to critique existing systems and advocate for change. As the world grapples with issues like climate change and economic inequality, the principles of political economy offer a vital tool for navigating these challenges.

Decoding Political Content: Strategies, Impact, and Audience Engagement Explained

You may want to see also

Public Policy: Formulation, implementation, and evaluation of government policies to address societal issues

Public policy serves as the backbone of government action, translating societal needs into tangible interventions. Formulation, the first stage, demands a delicate balance between evidence and ideology. Policymakers must sift through data, stakeholder interests, and political realities to craft solutions. For instance, addressing climate change requires integrating scientific research on emissions with economic models and public opinion surveys. This stage often involves trade-offs—prioritizing renewable energy subsidies might mean cutting funds from other sectors, illustrating the inherent complexity of policy design.

Implementation, the bridge between theory and practice, is where policies face their first real-world test. Success hinges on clear communication, adequate resources, and bureaucratic efficiency. Consider the rollout of healthcare reforms: training medical staff, updating IT systems, and educating the public are critical steps. However, even well-designed policies can falter if implementation is rushed or underfunded. The Affordable Care Act’s initial technical glitches highlight how logistical challenges can undermine public trust and policy effectiveness.

Evaluation, often overlooked, is the compass for future policy refinement. Rigorous assessment involves measuring outcomes against intended goals, identifying unintended consequences, and adapting strategies accordingly. For example, a policy to reduce school dropout rates might track graduation rates, but it should also examine whether it inadvertently widened achievement gaps among demographic groups. Cost-benefit analyses, impact studies, and stakeholder feedback are essential tools here. Without evaluation, policies risk becoming outdated or counterproductive, wasting resources and failing to address evolving societal needs.

A comparative lens reveals that public policy is not one-size-fits-all. Different political systems yield distinct approaches. Authoritarian regimes may prioritize swift implementation over stakeholder consultation, while democratic governments often face protracted debates. For instance, Sweden’s incremental approach to welfare reform contrasts with the U.S.’s more fragmented, crisis-driven policymaking. Such variations underscore the importance of context in shaping policy processes and outcomes.

Ultimately, public policy is a dynamic, iterative process requiring collaboration across sectors and disciplines. Policymakers must remain agile, responsive to feedback, and committed to evidence-based decision-making. By understanding the interplay of formulation, implementation, and evaluation, societies can better navigate complex challenges and build policies that truly serve the public good. Practical tips include fostering interdisciplinary teams, leveraging technology for data-driven insights, and maintaining transparency to sustain public support.

Politeness vs. Authenticity: Navigating Social Norms Without Compromising Yourself

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political science is the systematic study of politics, government, and power. It examines political systems, behaviors, institutions, policies, and theories to understand how societies make decisions and allocate resources.

The main subfields include comparative politics, international relations, political theory, public policy, public administration, and political methodology. Each focuses on different aspects of politics and governance.

While political science overlaps with disciplines like sociology, economics, and psychology, it specifically focuses on power, governance, and decision-making processes within and between political entities.

Graduates can pursue careers in government, law, public policy, journalism, international organizations, research, education, and advocacy, among other fields.