Political socialization is the process through which individuals acquire political values, beliefs, and behaviors, shaping their understanding of and engagement with the political world. It occurs primarily during childhood and adolescence but continues throughout life, influenced by various agents such as family, education, media, peers, and cultural institutions. This process not only determines how individuals perceive political systems and issues but also influences their level of political participation, party affiliation, and attitudes toward authority. By examining political socialization, we can better understand the roots of political ideologies, the stability of political systems, and the mechanisms through which societies transmit their political norms across generations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The process by which individuals acquire political values, beliefs, and behaviors, shaping their understanding of politics and their role within a political system. |

| Agents | Family, education system, peer groups, media, religious institutions, and personal experiences. |

| Timing | Begins in early childhood and continues throughout life, with the most significant impact during formative years. |

| Key Concepts | - Primary Socialization: Early childhood, primarily through family. - Secondary Socialization: Later stages, through schools, media, and peers. - Resocialization: Changing political beliefs due to significant events or experiences. |

| Influences | Cultural norms, socioeconomic status, political environment, historical events, and technological advancements. |

| Outcomes | Development of political identity, party affiliation, voting behavior, civic engagement, and attitudes toward authority. |

| Global Variations | Varies by country, influenced by political systems (e.g., democratic vs. authoritarian), cultural values, and historical contexts. |

| Contemporary Trends | Increased influence of social media, polarization, and global interconnectedness shaping political beliefs. |

| Challenges | Misinformation, political polarization, and declining trust in institutions impacting socialization processes. |

| Measurement | Surveys, interviews, and observational studies to assess political attitudes, knowledge, and behaviors. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Family Influence: Early political beliefs shaped by parents, siblings, and home environment dynamics

- Education Role: Schools, teachers, and curricula impact political attitudes and civic knowledge

- Media Impact: News, social media, and entertainment shape political perceptions and opinions

- Peer Groups: Friends, colleagues, and social circles influence political views and behaviors

- Cultural Norms: Societal values, traditions, and historical context mold political socialization processes

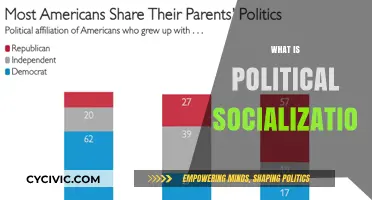

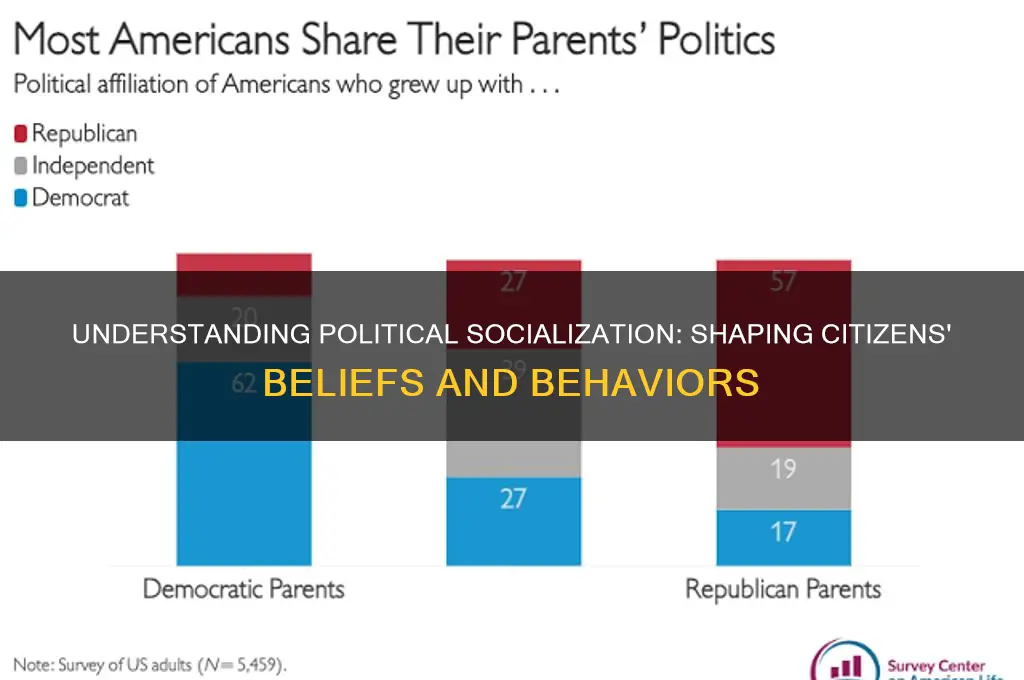

Family Influence: Early political beliefs shaped by parents, siblings, and home environment dynamics

The family is the first classroom of political socialization, where children absorb beliefs and attitudes long before they understand the words "Democrat" or "Republican." Parents, through their conversations, media choices, and even casual remarks, inadvertently teach their children about the world and their place in it. A study by the American Political Science Association found that children as young as five can articulate political preferences, often mirroring those of their parents. This early imprinting is not just about party affiliation; it includes attitudes toward authority, fairness, and social issues, forming the bedrock of political identity.

Consider the dinner table as a microcosm of political education. A parent’s offhand comment about taxes, a sibling’s rant about school policies, or a heated debate over a news story—all contribute to a child’s emerging worldview. For instance, a family that consistently criticizes government intervention may raise children skeptical of public programs, while one that praises community efforts might foster a belief in collective responsibility. Siblings, too, play a role; older brothers or sisters can introduce counter-narratives, creating internal debates that refine a child’s beliefs. This dynamic environment shapes not just what children think, but how they think about politics.

To maximize positive family influence, parents can adopt specific strategies. First, encourage open dialogue rather than monologue. Ask children their opinions on age-appropriate issues, such as school rules or neighborhood changes, to foster critical thinking. Second, expose them to diverse perspectives through books, documentaries, or community events, balancing the family’s dominant viewpoint. For children aged 8–12, this could mean discussing a local election or analyzing a political cartoon together. Finally, model respectful discourse, especially during disagreements, to teach that differing opinions are not threats but opportunities for growth.

However, family influence is not without risks. Overbearing parents or a monolithic home environment can stifle independent thought, leading to rigid ideologies. A cautionary example is the phenomenon of "political enmeshment," where a child’s identity becomes so intertwined with their family’s beliefs that they struggle to form their own. To avoid this, families should create space for questioning and exploration, particularly during adolescence, when youth are most likely to reevaluate inherited beliefs. Encouraging participation in extracurricular activities or peer groups with diverse backgrounds can provide counterbalancing perspectives.

In conclusion, the family’s role in political socialization is profound but not deterministic. While parents and siblings lay the foundation, children ultimately build their own political identities through experiences outside the home. By fostering an environment of curiosity, respect, and exposure to diversity, families can ensure their influence is a starting point, not an endpoint, in their child’s political journey. This approach not only shapes informed citizens but also nurtures the adaptability needed in an ever-changing political landscape.

Understanding the Political Freedom Index: A Comprehensive Guide to Global Liberties

You may want to see also

Education Role: Schools, teachers, and curricula impact political attitudes and civic knowledge

Schools serve as primary incubators for political socialization, systematically shaping students’ attitudes and knowledge through structured curricula, teacher interactions, and classroom environments. From elementary civics lessons to high school debates, educational institutions introduce foundational concepts like democracy, citizenship, and governance. For instance, a study by the Pew Research Center found that 72% of Americans recall learning about the three branches of government in school, highlighting the role of formal education in civic literacy. However, the depth and neutrality of this instruction vary widely, influenced by regional standards, teacher biases, and resource availability. This variability underscores the dual potential of schools: to either reinforce political norms or inadvertently sow confusion and apathy.

Teachers, as gatekeepers of curriculum delivery, wield disproportionate influence over students’ political development. Their personal beliefs, pedagogical styles, and engagement strategies can subtly or overtly shape classroom discourse. A teacher passionate about environmental policy might inspire students to prioritize green initiatives, while another skeptical of government intervention could foster cynicism. Research from the Journal of Political Science Education reveals that teachers’ political leanings correlate with students’ issue positions, particularly in contentious areas like taxation or immigration. To mitigate bias, educators must adopt balanced teaching methods, such as presenting multiple perspectives and encouraging critical analysis. For example, using primary sources like Supreme Court rulings or party platforms allows students to form opinions based on evidence rather than rhetoric.

Curricula themselves are not neutral tools but reflect societal values and historical contexts, often embedding implicit political messages. Textbooks, for instance, may glorify certain leaders or omit marginalized voices, shaping students’ understanding of national identity. In Texas, a 2021 curriculum overhaul mandated teaching “the benefits of fossil fuels,” illustrating how economic interests can infiltrate educational content. Conversely, countries like Finland integrate media literacy into their curricula, equipping students to discern political propaganda from factual information. Such examples demonstrate the need for transparent, inclusive curriculum design that fosters civic engagement rather than indoctrination.

The age at which political concepts are introduced also matters. Elementary students, aged 6–12, are more receptive to simple, values-based lessons, such as fairness and cooperation, which lay the groundwork for later political reasoning. By contrast, high schoolers, aged 14–18, benefit from complex discussions on policy trade-offs and ethical dilemmas. A practical tip for educators is to use age-appropriate simulations, like mock elections for younger students and model UN debates for older ones, to make abstract ideas tangible. Pairing these activities with reflective journaling can deepen students’ understanding of their own political beliefs and those of others.

Ultimately, the education system’s role in political socialization is both powerful and precarious. When schools, teachers, and curricula collaborate effectively, they cultivate informed, engaged citizens capable of navigating a polarized world. However, missteps in this process risk perpetuating misinformation or alienating students from civic life. Policymakers and educators must prioritize ongoing training in political literacy, curriculum audits for bias, and cross-partisan collaboration to ensure schools fulfill their democratic mission. After all, the health of a nation’s political culture begins in the classroom.

Did the Grammys Ban Politics? Unraveling the Awards' Stance

You may want to see also

Media Impact: News, social media, and entertainment shape political perceptions and opinions

Media consumption is a cornerstone of political socialization, with news outlets, social platforms, and entertainment subtly sculpting how individuals perceive political issues and actors. Consider the daily news cycle: a study by the Pew Research Center found that 53% of U.S. adults often get their news from digital devices, where algorithms prioritize sensational or polarizing content. This "filter bubble" effect reinforces existing beliefs while limiting exposure to opposing viewpoints, fostering ideological echo chambers. For instance, a person who frequently engages with conservative news sources is more likely to adopt right-leaning views, not because of the content’s inherent truth but due to its repetitive reinforcement.

Social media amplifies this dynamic through its interactive nature. Platforms like Twitter and Instagram allow users to curate their feeds, follow like-minded individuals, and engage in debates that often devolve into tribalistic exchanges. A 2021 report by the Knight Foundation revealed that 55% of Americans aged 18–29 get their news from social media, where misinformation spreads six times faster than factual information. This isn’t just about falsehoods; it’s about the emotional framing of issues. A viral post about a political scandal, even if exaggerated, can shape public opinion more effectively than a nuanced news article, as it taps into outrage or fear—emotions that drive engagement and memory retention.

Entertainment, too, plays a covert role in political socialization. Television shows, movies, and streaming series often embed political themes or ideologies, normalizing certain perspectives for audiences. For example, *The West Wing* romanticized Democratic governance, while *24* often portrayed aggressive national security policies as necessary. A study published in *Political Communication* found that viewers of politically themed entertainment are 20% more likely to adopt the ideologies portrayed, especially if the content aligns with their preexisting leanings. This isn’t limited to scripted shows; late-night comedy hosts like Stephen Colbert and Trevor Noah blend humor with political commentary, influencing younger viewers who may trust comedians more than traditional journalists.

To mitigate media’s polarizing effects, individuals can adopt a three-step approach. First, diversify sources: intentionally follow outlets with differing perspectives, such as pairing *The New York Times* with *The Wall Street Journal*. Second, fact-check actively: tools like Snopes or Reuters Fact Check can verify claims before sharing or internalizing them. Third, limit emotional engagement: take breaks from social media and analyze why a post triggers a strong reaction. For parents and educators, teaching media literacy is crucial; studies show that students who receive media literacy training are 30% less likely to accept misinformation as truth.

Ultimately, media’s role in political socialization is both powerful and pervasive, shaping not just what we think but how we think. By understanding its mechanisms—from algorithmic biases to emotional manipulation—individuals can reclaim agency over their political perceptions. The goal isn’t to avoid media but to engage with it critically, recognizing that every headline, tweet, or TV episode is a piece of a larger narrative, one that we have the power to question and reinterpret.

Africa's Political Influence: Underrated, Overlooked, or Globally Relevant?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Peer Groups: Friends, colleagues, and social circles influence political views and behaviors

Peer groups wield significant influence over political socialization, often shaping views and behaviors in subtle yet profound ways. Consider the dynamics of a high school classroom where a passionate debate on climate policy unfolds. A student, initially indifferent, finds themselves swayed by the articulate arguments of their peers, adopting a stance they might not have otherwise considered. This microcosm illustrates how friends, colleagues, and social circles act as crucibles for political identity formation, particularly during formative years. Research indicates that adolescents aged 14–18 are most susceptible to peer influence, with 60% reporting shifts in political beliefs due to group discussions. Such environments foster not only the exchange of ideas but also the internalization of norms, creating a feedback loop where conformity and individuality coexist.

To harness the power of peer groups effectively, intentional engagement is key. For instance, organizing diverse discussion forums in workplaces or community centers can expose individuals to contrasting viewpoints, mitigating echo chamber effects. A study by the Pew Research Center found that employees who participated in politically diverse teams were 35% more likely to moderate their views over time. However, caution is warranted: unchecked groupthink can stifle critical thinking. Facilitators should encourage active listening and evidence-based arguments, ensuring that dialogue remains constructive. Practical tips include setting ground rules for debates, such as limiting personal attacks and requiring sources for claims, to foster a balanced exchange.

The persuasive power of peer groups extends beyond verbal discourse, often manifesting in behavioral emulation. Observing a colleague consistently volunteering for local campaigns or a friend boycotting certain brands for political reasons can inspire similar actions. This phenomenon, known as social proof, is particularly potent among young adults aged 18–25, who are twice as likely to engage in political activism if their peers do so. To leverage this, organizations can create peer-led initiatives, such as youth-driven voter registration drives or workplace sustainability committees, amplifying collective impact. Yet, it’s crucial to avoid peer pressure tactics that alienate individuals, instead emphasizing shared values and voluntary participation.

Comparatively, the influence of peer groups differs across cultures and contexts. In collectivist societies, where group harmony is prioritized, political conformity tends to be higher, whereas individualistic cultures may see greater diversity of opinion. For instance, a study in Japan revealed that 70% of respondents aligned their political views with their social circles, compared to 45% in the United States. This highlights the need for culturally sensitive approaches when designing interventions. In multicultural settings, fostering cross-group interactions can bridge divides, while in homogeneous groups, introducing external perspectives through guest speakers or media can broaden horizons.

Ultimately, peer groups serve as both mirrors and catalysts in political socialization, reflecting existing beliefs while propelling change. By understanding their dynamics, individuals and institutions can navigate this influence strategically. Whether through structured dialogues, behavioral modeling, or cultural adaptation, the goal is to transform peer pressure into a force for informed, inclusive political engagement. After all, in the tapestry of political identity, the threads woven by friends, colleagues, and social circles are among the most vibrant and enduring.

Political Marriages: Power, Strategy, and Union in Global Leadership Dynamics

You may want to see also

Cultural Norms: Societal values, traditions, and historical context mold political socialization processes

Cultural norms, deeply embedded in societal values, traditions, and historical context, serve as the bedrock of political socialization. These norms dictate acceptable behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs, shaping how individuals perceive and engage with political systems. For instance, in societies where respect for authority is a core value, citizens are more likely to internalize deference to government institutions, even if those institutions are flawed. This internalization begins early, often through family discussions, school curricula, and media portrayals that reinforce the importance of obedience to established power structures.

Consider the role of traditions in political socialization. Annual celebrations like Independence Day in the United States or Bastille Day in France are not merely festive occasions; they are rituals that reinforce national identity and political ideology. These events often include narratives of historical struggles and triumphs, subtly instilling pride in one’s political system and a sense of duty to uphold its principles. For children, participating in such traditions can be a formative experience, embedding political values before they even begin to critically analyze them.

Historical context further amplifies the impact of cultural norms on political socialization. Societies with a history of authoritarian rule, for example, may develop a collective skepticism toward government, even after transitioning to democracy. This skepticism can manifest in lower voter turnout, distrust of political institutions, and a preference for informal, community-based governance structures. Conversely, nations with a history of stable democratic governance often foster a culture of civic engagement, where participation in political processes is seen as both a right and a responsibility.

To illustrate, compare the political socialization processes in Japan and India. In Japan, the emphasis on harmony and consensus in cultural norms translates into a political system that values stability and incremental change. Citizens are socialized to prioritize collective well-being over individual political expression, often leading to high levels of trust in government but lower rates of political activism. In contrast, India’s diverse cultural traditions and history of anti-colonial struggle have fostered a more contentious but vibrant political environment. Here, political socialization often involves debates, protests, and a strong sense of individual agency in shaping governance.

Practical tips for understanding and navigating these dynamics include studying local histories, engaging with community elders to uncover unwritten norms, and analyzing media content for implicit political messages. For educators and parents, incorporating diverse perspectives into discussions about politics can help young people develop a more nuanced understanding of their societal context. By recognizing how cultural norms shape political socialization, individuals can better navigate their political environments, whether advocating for change or preserving established values.

Clinic's Political Storm: Unraveling the Controversy and Its Impact

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political socialization is the process through which individuals acquire political values, beliefs, and behaviors, shaping their understanding of politics and their role within a political system.

Political socialization occurs through various agents such as family, schools, media, peers, and personal experiences, which collectively influence an individual’s political outlook.

Political socialization begins in early childhood, often within the family, as children observe and internalize the political attitudes and behaviors of their parents or caregivers.

Yes, political socialization is not static; it can evolve due to life experiences, exposure to new ideas, education, and changing societal norms.

Political socialization is crucial as it shapes citizens’ engagement with politics, influences their voting behavior, and contributes to the stability and functioning of democratic systems.