Political patronage refers to the practice of appointing individuals to government positions or awarding contracts based on their political support, loyalty, or affiliation rather than their qualifications or merit. Often rooted in the exchange of favors, this system allows those in power to reward allies, consolidate influence, and maintain political networks. While it can foster party cohesion and ensure alignment with governing agendas, it frequently undermines transparency, efficiency, and fairness in public administration. Critics argue that patronage perpetuates corruption, stifles competent governance, and erodes public trust in institutions, as it prioritizes political loyalty over expertise and public service. Despite its controversial nature, patronage remains a pervasive feature in many political systems worldwide, reflecting the intersection of power, loyalty, and resource distribution.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The practice of appointing individuals to government positions based on political loyalty, support, or affiliation rather than merit or qualifications. |

| Purpose | To reward political supporters, consolidate power, and ensure loyalty within the ruling party or administration. |

| Common Practice | Widespread in systems with weak civil service protections, high corruption, or strong partisan politics. |

| Examples | Appointing campaign donors, party members, or allies to key government roles (e.g., ambassadors, agency heads). |

| Impact on Meritocracy | Undermines merit-based hiring, leading to less competent individuals in critical positions. |

| Legal Status | Often legal but ethically controversial; some countries have laws to limit or regulate it. |

| Public Perception | Generally viewed negatively as it fosters corruption, inefficiency, and nepotism. |

| Historical Context | Dates back to ancient political systems; notably prevalent in the U.S. "spoils system" of the 19th century. |

| Modern Examples | Observed in countries like India, Brazil, and the U.S. during partisan administrations. |

| Alternatives | Merit-based hiring, civil service reforms, and transparent appointment processes. |

| Global Prevalence | More common in developing democracies or countries with weak institutions. |

| Economic Impact | Can lead to inefficient governance, misallocation of resources, and reduced public trust. |

| Reform Efforts | Advocacy for independent oversight, anti-corruption laws, and public accountability measures. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition and Origins: Brief history and core meaning of political patronage in governance systems

- Mechanisms and Practices: Methods used to distribute favors, jobs, or resources to supporters

- Impact on Governance: Effects on efficiency, corruption, and public trust in institutions

- Legal and Ethical Issues: Examination of laws and moral concerns surrounding patronage systems

- Global Examples: Case studies of patronage in different countries and political contexts

Definition and Origins: Brief history and core meaning of political patronage in governance systems

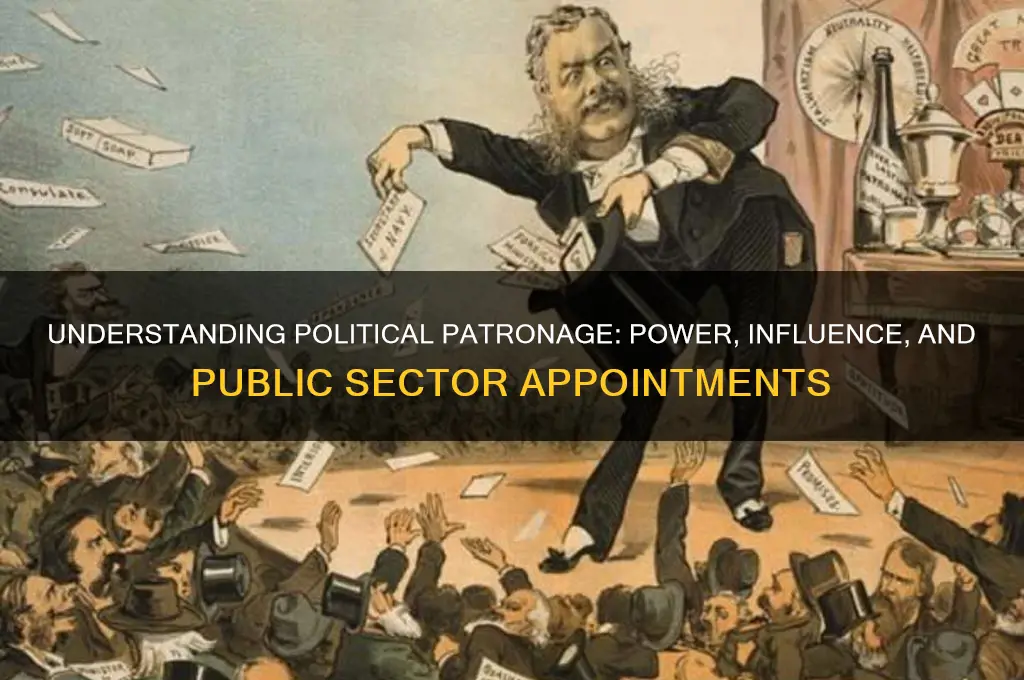

Political patronage, the practice of rewarding supporters with jobs, contracts, or favors, has deep roots in governance systems. Its origins trace back to ancient civilizations where rulers distributed resources to secure loyalty and maintain power. In Rome, for instance, patrons provided protection and resources to clients in exchange for political and social support. This reciprocal relationship formed the bedrock of early patronage systems, blending personal and political obligations. Over centuries, this dynamic evolved but retained its core essence: leveraging power to consolidate influence through strategic distribution of benefits.

Analyzing its historical trajectory reveals patronage as both a tool of stability and a source of corruption. During the Renaissance, European monarchs used patronage to foster the arts and sciences, sponsoring figures like Michelangelo and Galileo. Yet, this same mechanism often led to nepotism and inefficiency, as qualifications took a backseat to loyalty. In the American context, the spoils system of the 19th century epitomized patronage, with Andrew Jackson appointing supporters to government posts. While this practice aimed to democratize access to power, it also undermined meritocracy, prompting reforms like the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883.

The core meaning of political patronage lies in its dual nature: a means of governance and a potential threat to it. At its best, patronage can mobilize resources and build coalitions, fostering unity within a ruling party. However, unchecked, it breeds cronyism, erodes public trust, and distorts policy-making. For instance, in developing nations, patronage networks often prioritize personal gain over public welfare, hindering economic and social progress. Understanding this duality is crucial for distinguishing constructive patronage from its abusive forms.

To navigate the complexities of patronage, consider its structural role in governance systems. In democracies, patronage can serve as a mechanism for power-sharing, ensuring diverse groups have a stake in the system. However, transparency and accountability are essential safeguards. Institutions like independent oversight bodies and robust civil service systems can mitigate risks. For practitioners, the takeaway is clear: patronage, when tempered by ethical constraints, can be a stabilizing force; without them, it becomes a corrosive agent. Balancing these dynamics requires vigilance, reform, and a commitment to the public good.

Mastering Political Psychology: A Guide to Becoming a Political Psychologist

You may want to see also

Mechanisms and Practices: Methods used to distribute favors, jobs, or resources to supporters

Political patronage, the practice of distributing favors, jobs, or resources to supporters, relies on a variety of mechanisms and practices that are both overt and subtle. One of the most direct methods is appointment power, where elected officials or party leaders fill government positions with loyalists rather than the most qualified candidates. This is often seen in the appointment of cabinet members, agency heads, or local administrators. For instance, in the United States, the "spoils system" of the 19th century institutionalized this practice, though reforms like the Pendleton Act of 1883 aimed to curb it. Despite such reforms, appointments remain a key tool for rewarding supporters, ensuring their continued loyalty and influence.

Another mechanism is contract allocation, where government contracts for infrastructure, services, or supplies are awarded to businesses or individuals tied to the ruling party. This practice is particularly prevalent in countries with weak transparency and accountability systems. For example, in some African and Latin American nations, construction contracts are often given to companies owned by party donors or allies, regardless of competitive bids. This not only rewards supporters but also creates a cycle of dependency, as beneficiaries are incentivized to maintain the status quo to secure future contracts.

Resource distribution is a third method, often employed in regions where the state controls essential goods or services. In rural areas, access to water, electricity, or agricultural subsidies may be granted selectively to communities or individuals who demonstrate political loyalty. This tactic is especially effective in developing countries, where state resources are scarce and highly valued. For instance, in some Indian states, irrigation water is allocated disproportionately to villages that vote for the ruling party, ensuring their continued support in elections.

A more subtle practice is symbolic recognition, which involves bestowing honors, titles, or public accolades on supporters. While this does not confer material benefits, it enhances the social and political standing of recipients, reinforcing their allegiance. Examples include awarding national medals, naming public buildings after allies, or granting honorary positions. This method is often used in conjunction with other mechanisms to create a multi-layered system of rewards.

Lastly, legislative favoritism involves crafting policies or laws that disproportionately benefit specific groups or regions aligned with the ruling party. This can range from tax breaks for certain industries to targeted funding for particular constituencies. For instance, in the U.S., "pork barrel" spending—the allocation of federal funds for localized projects—is often used to reward political supporters. While such practices can stimulate local economies, they also raise ethical concerns about fairness and equitable resource allocation.

In conclusion, the mechanisms of political patronage are diverse and adaptable, reflecting the ingenuity of those in power to maintain control. While some methods are overt and transactional, others are subtle and symbolic, creating a complex web of obligations and rewards. Understanding these practices is crucial for assessing the health of democratic institutions and the potential for reform.

Empower Your Voice: Practical Steps for Effective Political Action

You may want to see also

Impact on Governance: Effects on efficiency, corruption, and public trust in institutions

Political patronage, the practice of appointing individuals to government positions based on loyalty rather than merit, has profound implications for governance. By prioritizing allegiance over competence, it undermines efficiency, fosters corruption, and erodes public trust in institutions. Consider the case of a public health department where a politically connected but unqualified individual is appointed as director. Their lack of expertise could lead to mismanaged resources, delayed responses to health crises, and ultimately, poorer health outcomes for the population. This example illustrates how patronage directly compromises the effectiveness of public services.

To mitigate the impact of patronage on efficiency, governments must adopt transparent hiring practices. Implementing merit-based selection processes, such as standardized tests and independent review panels, can ensure that qualified individuals are appointed to critical roles. For instance, countries like Singapore and Denmark have maintained high governance efficiency by rigorously adhering to meritocracy, setting a benchmark for others. However, caution must be exercised to avoid tokenism, where merit-based systems are superficially applied while political influence still dominates behind the scenes. Regular audits and public accountability mechanisms are essential to safeguard the integrity of these processes.

Corruption thrives in environments where political patronage is rampant. When appointments are made based on loyalty, officials often feel obligated to repay their benefactors, leading to favoritism, embezzlement, and misuse of public funds. A study by Transparency International found that countries with high levels of patronage consistently rank lower on corruption perception indices. For example, in nations where political appointments dominate the judiciary, the rule of law weakens, and impunity becomes the norm. Combating this requires robust anti-corruption frameworks, including whistleblower protections and stringent penalties for malfeasance.

Public trust in institutions is perhaps the most fragile casualty of political patronage. When citizens perceive that government positions are awarded as political rewards rather than earned through merit, their faith in the system diminishes. This disillusionment can manifest in declining voter turnout, increased skepticism of public policies, and even social unrest. Rebuilding trust demands not only systemic reforms but also proactive communication. Governments must engage with the public, explain their decision-making processes, and demonstrate tangible improvements in governance. For instance, publishing appointment criteria and outcomes can enhance transparency and reassure citizens that merit is valued.

In conclusion, the impact of political patronage on governance is multifaceted and detrimental. It hampers efficiency by placing unqualified individuals in critical roles, breeds corruption by fostering a culture of reciprocity, and undermines public trust by signaling that loyalty trumps competence. Addressing these challenges requires a combination of structural reforms, accountability measures, and public engagement. By prioritizing merit and transparency, governments can mitigate the adverse effects of patronage and strengthen the foundations of effective governance.

The FBI's Political Role: Uncovering Bias and Influence in Investigations

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Legal and Ethical Issues: Examination of laws and moral concerns surrounding patronage systems

Political patronage, the practice of appointing supporters to government positions as a reward for their loyalty, raises significant legal and ethical concerns. While it can foster party cohesion and ensure aligned governance, it often undermines meritocracy, transparency, and public trust. The legal framework surrounding patronage varies widely, with some jurisdictions explicitly prohibiting it, while others tolerate it within certain bounds. For instance, the U.S. Pendleton Act of 1883 sought to curb patronage by establishing a merit-based civil service system, yet loopholes persist, allowing for political appointments in key roles. In contrast, countries like India have stricter laws, such as the Prevention of Corruption Act, which criminalizes favoritism in public appointments. These legal disparities highlight the global struggle to balance political loyalty with administrative integrity.

Ethically, patronage systems challenge the principles of fairness and equality. By prioritizing political allegiance over competence, they disenfranchise qualified individuals and perpetuate inequality. Consider the case of a public health department where a politically connected but inexperienced appointee oversees critical decisions, potentially endangering lives. Such scenarios underscore the moral dilemma: does loyalty to a party justify compromising public welfare? Critics argue that patronage fosters corruption, as appointees may feel obligated to repay their benefactors through favors or policy concessions. This quid pro quo dynamic erodes institutional integrity and distorts governance priorities, often at the expense of the public good.

A comparative analysis reveals that the ethical concerns surrounding patronage are not merely theoretical but have tangible consequences. In countries with high levels of patronage, such as certain post-Soviet states, corruption indices tend to be higher, and public trust in government lower. Conversely, nations with robust anti-patronage laws, like Sweden, consistently rank among the least corrupt and most transparent. This correlation suggests that legal frameworks play a pivotal role in mitigating the ethical risks of patronage. However, even in jurisdictions with stringent laws, enforcement remains a challenge, as political elites often exploit ambiguities or wield influence to circumvent regulations.

To address these issues, policymakers must adopt a multi-pronged approach. First, strengthen legal frameworks by closing loopholes and imposing stricter penalties for patronage-related offenses. Second, enhance transparency through mandatory disclosure of appointees' qualifications and the criteria for their selection. Third, foster a culture of accountability by empowering independent oversight bodies to investigate and sanction violations. Practical steps include requiring public hearings for high-level appointments and establishing whistleblower protections to encourage reporting of abuses. While these measures cannot eliminate patronage entirely, they can minimize its adverse effects and restore public confidence in governance.

Ultimately, the legal and ethical issues surrounding patronage systems demand urgent attention. By examining global practices, identifying systemic vulnerabilities, and implementing targeted reforms, societies can strike a balance between political loyalty and administrative integrity. The challenge lies not in eradicating patronage—an arguably impossible feat—but in containing its excesses and ensuring that public service remains a domain of competence, not cronyism. This requires not only robust laws but also a collective commitment to ethical governance, where the common good transcends partisan interests.

Gracefully Cancelling Plans: A Guide to Polite and Respectful Communication

You may want to see also

Global Examples: Case studies of patronage in different countries and political contexts

Political patronage, the practice of rewarding supporters with jobs, contracts, or favors, manifests differently across the globe, shaped by cultural norms, political systems, and historical contexts. Examining case studies from diverse countries illuminates its multifaceted nature and impact.

Consider the United States, where patronage has historically been a cornerstone of political machines, particularly in urban areas. The Tammany Hall machine in 19th-century New York City is a notorious example. Immigrants, often marginalized from mainstream politics, were offered jobs and services in exchange for votes, solidifying the machine's power. While reforms like the Pendleton Act of 1883 aimed to curb patronage by introducing merit-based civil service exams, its remnants persist, with political appointments often prioritizing loyalty over expertise.

In contrast, Japan's Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has long relied on a system of "pork-barrel politics," channeling government funds to local constituencies in exchange for electoral support. This practice, known as "zoku giin" (tribal politics), has been instrumental in the LDP's dominance since its formation in 1955. While criticized for fostering inefficiency and corruption, it has also been credited with fostering regional development and maintaining political stability.

The African context presents a different picture. In Nigeria, patronage networks often revolve around ethnic and religious affiliations. Politicians distribute resources and appointments based on tribal or religious loyalty, perpetuating divisions and hindering national unity. This system, known as "prebendalism," has been linked to widespread corruption, inequality, and underdevelopment.

A comparative analysis reveals that while patronage can provide short-term benefits like political stability and localized development, its long-term consequences are often detrimental. It undermines meritocracy, fosters corruption, and exacerbates social divisions. To combat these negative effects, countries have implemented various reforms, including merit-based hiring, transparency initiatives, and stronger anti-corruption laws. However, the deeply ingrained nature of patronage in many political systems makes its eradication a complex and ongoing challenge.

Mastering Politics: Essential Steps to Expand Your Political Knowledge

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political patronage is the practice of appointing or favoring individuals to government positions or contracts based on their political support, loyalty, or affiliation rather than their qualifications or merit.

Political patronage prioritizes political loyalty or connections in selecting individuals for roles, while merit-based appointments focus on qualifications, skills, and experience as the primary criteria.

Political patronage can lead to inefficiency, corruption, and reduced public trust in government, as unqualified individuals may be placed in critical positions, undermining effective governance.

While not always illegal, political patronage can be controversial and is often regulated to prevent abuse. In some cases, it may violate laws against nepotism, corruption, or discrimination.

In limited cases, political patronage can reward loyal supporters and consolidate political power. However, its negative consequences, such as undermining meritocracy and fostering corruption, typically outweigh any potential benefits.