Political paranoia refers to an intense and often irrational fear or suspicion of political institutions, leaders, or ideologies, typically rooted in the belief that hidden forces are conspiring to undermine one's freedoms, rights, or way of life. It can manifest as a pervasive distrust of government, media, or other powerful entities, often fueled by conspiracy theories, misinformation, or historical grievances. This mindset can lead individuals or groups to perceive threats where none exist, fostering a climate of fear, division, and polarization. While skepticism of authority is a healthy aspect of democratic societies, political paranoia crosses into dangerous territory when it distorts reality, erodes trust in legitimate institutions, and incites harmful actions or policies. Understanding its causes, manifestations, and consequences is crucial for addressing its impact on public discourse, governance, and social cohesion.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Exaggerated Threat Perception | Overestimation of threats from political opponents, often without concrete evidence. |

| Conspiracy Theories | Belief in hidden plots or schemes by powerful groups to undermine one's political ideology. |

| Us vs. Them Mentality | Division of society into extreme categories of allies and enemies. |

| Persecution Complex | Feeling unfairly targeted or victimized by political adversaries or the system. |

| Distrust of Institutions | Lack of faith in government, media, or other institutions perceived as biased or corrupt. |

| Information Echo Chambers | Reliance on sources that reinforce existing beliefs, ignoring contradictory evidence. |

| Hypervigilance | Constant monitoring of political developments for perceived threats or attacks. |

| Polarized Thinking | Black-and-white thinking, with no middle ground in political discourse. |

| Emotional Intensity | Strong emotional reactions (fear, anger) to political events or opposing views. |

| Resistance to Dialogue | Avoidance of constructive debate, viewing compromise as betrayal of principles. |

| Historical Grievances | Fixation on past wrongs or injustices to justify current political paranoia. |

| Dehumanization of Opponents | Viewing political adversaries as inherently evil or unworthy of respect. |

| Apocalyptic Thinking | Belief that political failures or opposition will lead to catastrophic outcomes. |

| Propaganda Susceptibility | Easy acceptance of politically aligned narratives without critical evaluation. |

| Social Media Amplification | Spread and reinforcement of paranoid beliefs through online platforms and algorithms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical origins of political paranoia

Political paranoia, as a phenomenon, has deep historical roots that can be traced back to the earliest forms of organized governance. One of the earliest examples is the reign of Roman Emperor Tiberius (14–37 AD), whose later years were marked by intense suspicion and fear of conspiracies. Tiberius retreated to the island of Capri, where he orchestrated a series of purges, executing or exiling perceived enemies, often based on flimsy evidence. This behavior exemplifies how political paranoia can lead to authoritarianism and the erosion of trust within a ruling elite. The Roman case highlights that political paranoia is not merely a modern affliction but a recurring theme in the history of power.

To understand the origins of political paranoia, consider the role of uncertainty in early political systems. In medieval Europe, monarchs often relied on networks of spies and informants to detect threats to their rule. The lack of centralized institutions and the prevalence of feudal loyalties created an environment ripe for suspicion. For instance, the reign of King Henry VIII of England (1491–1547) was characterized by his relentless pursuit of perceived traitors, culminating in the execution of high-ranking officials like Thomas More and Anne Boleyn. This historical context underscores how political paranoia often thrives in systems where power is concentrated and accountability is limited.

A comparative analysis of political paranoia reveals its adaptability across cultures. In ancient China, the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC) under Emperor Qin Shi Huang provides a striking example. The emperor’s obsession with immortality and fear of assassination led to extreme measures, including the burning of books and the burial of scholars alive. Similarly, in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin (1924–1953), paranoia fueled the Great Purge, during which millions were executed or sent to labor camps. These examples illustrate that political paranoia is not confined to a single culture or era but is a universal response to the insecurities of power.

Practical insights into the historical origins of political paranoia can be derived from the study of institutional failures. For instance, the absence of checks and balances in absolute monarchies and totalitarian regimes often amplifies paranoid tendencies. In contrast, democratic systems, with their emphasis on transparency and accountability, tend to mitigate such behaviors. A key takeaway is that political paranoia is not inevitable but is often a product of structural vulnerabilities. To guard against it, modern societies must prioritize institutional safeguards, such as an independent judiciary and a free press, which act as antidotes to the excesses of power.

Finally, a descriptive examination of historical narratives reveals the human cost of political paranoia. The Salem Witch Trials (1692–1693) in colonial America serve as a poignant example. Fueled by mass hysteria and unfounded accusations, the trials resulted in the execution of 20 people and the imprisonment of hundreds more. This episode demonstrates how political paranoia can metastasize into societal paranoia, destroying lives and communities. By studying such historical cases, we gain a deeper understanding of the mechanisms that drive paranoid behavior and the importance of fostering a culture of rationality and empathy to prevent its recurrence.

Hazing in Fraternities: A Political Power Play or Tradition?

You may want to see also

Psychological factors driving political distrust

Political paranoia often stems from deep-seated psychological factors that amplify distrust in institutions and leaders. One key driver is cognitive bias, particularly confirmation bias, where individuals selectively interpret information to reinforce pre-existing beliefs. For instance, a person convinced of government corruption will amplify minor scandals while dismissing evidence of transparency. This mental shortcut, while efficient, distorts reality and fuels mistrust. Studies show that prolonged exposure to partisan media exacerbates this bias, creating echo chambers that deepen paranoia. To mitigate this, actively seek diverse viewpoints and fact-check sources before forming conclusions.

Another psychological factor is perceived powerlessness, which arises when individuals feel their voices are ignored by those in authority. This sense of helplessness can manifest as suspicion or hostility toward political systems. For example, communities marginalized by policy decisions often develop a collective distrust rooted in historical grievances. Psychologists suggest that fostering agency—through local activism or community engagement—can counteract this feeling. Practical steps include joining grassroots organizations or participating in town hall meetings to regain a sense of control over political processes.

Trauma and fear also play a significant role in political paranoia. Individuals who have experienced economic instability, violence, or systemic failures are more likely to view political actions through a lens of threat. For instance, survivors of authoritarian regimes often exhibit heightened distrust of government initiatives, even in democratic settings. Therapists recommend addressing underlying trauma through counseling or support groups to reduce fear-driven paranoia. Mindfulness practices, such as meditation, can help individuals differentiate between past trauma and present realities.

Lastly, social influence amplifies political distrust through group dynamics. Peer pressure, family beliefs, and online communities can normalize paranoid thinking, making it seem rational. A study found that 60% of participants adopted more extreme political views after prolonged exposure to like-minded groups. To break this cycle, cultivate relationships with individuals holding differing opinions and engage in respectful dialogue. Limiting time on polarizing social media platforms can also reduce the spread of paranoid narratives.

In summary, political paranoia is not merely a reaction to external events but a complex interplay of cognitive, emotional, and social factors. By understanding these psychological drivers, individuals can take proactive steps to foster healthier political engagement. Whether through bias awareness, empowerment, trauma healing, or diversifying social circles, addressing these root causes is essential for rebuilding trust in political systems.

Merry Christmas or Happy Holidays: Navigating Seasonal Greetings Sensitively

You may want to see also

Media’s role in amplifying paranoia

Media outlets, driven by the imperative to capture attention, often prioritize sensationalism over nuance. This tendency exacerbates political paranoia by amplifying extreme viewpoints and framing issues in stark, emotionally charged terms. For instance, a minor policy disagreement might be portrayed as an existential threat to democracy, leveraging fear to engage audiences. Such framing not only distorts reality but also reinforces a siege mentality among viewers or readers, making them more susceptible to conspiratorial thinking.

Consider the mechanics of social media algorithms, which reward engagement by surfacing content that provokes strong reactions. A study by the Pew Research Center found that 64% of adults in the U.S. occasionally encounter conspiracy theories on social platforms. These algorithms create echo chambers where users are repeatedly exposed to information that aligns with their preexisting beliefs, intensifying paranoia. For example, a user skeptical of government intentions might see increasingly radical content, from critiques of policy to unfounded claims of secret plots, normalizing distrust.

To mitigate media-driven paranoia, consumers must adopt critical media literacy skills. Start by verifying sources: cross-reference information from at least three independent outlets before accepting it as fact. Limit exposure to social media by setting daily usage caps—for instance, no more than 30 minutes on platforms known for polarizing content. Engage with diverse perspectives by following accounts or publications that challenge your worldview. Finally, pause before sharing content: ask whether it appeals to emotion rather than evidence, a hallmark of paranoia-inducing material.

The role of traditional media in amplifying paranoia is equally significant, particularly through the use of loaded language and selective storytelling. A 2020 analysis by the Shorenstein Center revealed that terms like “crisis” or “scandal” appeared in 78% of political headlines during election seasons, even when the underlying issues were routine. This hyperbolic tone primes audiences to perceive threats where none exist, fostering a climate of perpetual anxiety. Journalists and editors must prioritize accuracy over clicks, recognizing their responsibility in shaping public perception.

Ultimately, the media’s amplification of paranoia is a symptom of broader systemic issues, from profit-driven content models to societal polarization. However, individual and collective action can counteract this trend. By demanding higher standards from media creators and cultivating a discerning approach to consumption, audiences can reduce the spread of paranoia. The goal is not to eliminate disagreement but to ensure it is grounded in reality, fostering informed discourse rather than fear-driven division.

Navigating Political Risks: Strategies for Effective Assessment and Mitigation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political paranoia in authoritarian regimes

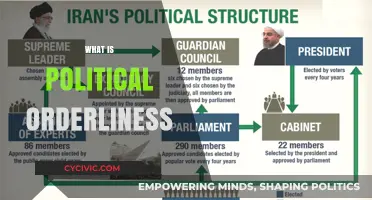

Political paranoia thrives in authoritarian regimes, where the state’s survival hinges on manufacturing fear and distrust. Unlike democracies, which often foster transparency and accountability, authoritarian systems rely on controlling information and suppressing dissent. This creates an environment where paranoia becomes a tool for consolidation of power. Leaders in such regimes frequently portray external forces—foreign governments, NGOs, or minority groups—as existential threats, justifying draconian measures to protect the nation. For instance, the Soviet Union under Stalin labeled intellectuals and minorities as "enemies of the state," leading to purges and mass surveillance. This pattern persists today in regimes like North Korea, where state propaganda incessantly warns of foreign conspiracies to destabilize the country.

To understand how political paranoia operates in authoritarian regimes, consider its three-step mechanism: identification of threats, amplification of fear, and mobilization of control. First, the regime identifies real or imagined threats, often scapegoating specific groups or nations. Second, state-controlled media amplifies these threats, creating a narrative of constant danger. Finally, the regime mobilizes its apparatus—police, military, or surveillance technology—to neutralize perceived threats, often at the expense of civil liberties. In China, for example, the government’s crackdown on Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang is framed as a necessary response to "separatist terrorism," despite widespread international condemnation of human rights abuses. This cycle not only sustains the regime’s grip on power but also fosters a culture of suspicion among citizens.

A comparative analysis reveals that political paranoia in authoritarian regimes differs fundamentally from its manifestation in democracies. While democratic societies may experience paranoia during crises (e.g., McCarthyism in the U.S.), checks and balances often limit its scope. In authoritarian regimes, however, paranoia is institutionalized. It becomes the bedrock of governance, shaping policies, education, and even personal relationships. Citizens are incentivized to report suspicious behavior, blurring the line between loyalty and fear. For instance, East Germany’s Stasi relied on a vast network of informants, turning neighbors and family members into agents of surveillance. This systemic paranoia not only suppresses dissent but also erodes trust, leaving society fragmented and vulnerable.

Practical tips for recognizing political paranoia in authoritarian regimes include monitoring state rhetoric for repetitive threat narratives, censorship of dissenting voices, and expansion of surveillance measures. Look for patterns where the regime consistently blames external or internal "enemies" for domestic problems, rather than addressing systemic issues. Additionally, observe how the state responds to criticism—harsh crackdowns or smear campaigns are red flags. For those living under such regimes, staying informed through independent sources and building trusted networks can mitigate the effects of paranoia. However, caution is essential; engaging in open dissent can lead to severe repercussions, making subtle resistance—such as sharing information discreetly—a safer strategy.

Ultimately, political paranoia in authoritarian regimes is not merely a psychological phenomenon but a strategic instrument of control. By weaponizing fear, these regimes ensure their survival while stifling individual freedoms. Understanding its mechanisms and manifestations is crucial for both those living under such systems and external observers. While complete eradication of paranoia in these contexts may be unrealistic, awareness and strategic resistance can create cracks in the regime’s foundation, paving the way for potential change. The challenge lies in balancing the need for caution with the imperative for action, a delicate task in environments where paranoia is both pervasive and punitive.

Unveiling the Dark Side: Political Bosses and Their Corrupt Practices

You may want to see also

Impact on democratic decision-making processes

Political paranoia, characterized by an irrational fear of threats to power or societal order, can profoundly distort democratic decision-making. When leaders or citizens succumb to this mindset, they often prioritize perceived survival over reasoned deliberation. For instance, during the Cold War, McCarthyism in the United States led to baseless accusations of communism, stifling dissent and undermining trust in public institutions. This historical example illustrates how paranoia can erode the very foundations of democracy by replacing evidence-based discourse with fear-driven narratives.

To mitigate the impact of political paranoia on democratic processes, it is essential to foster transparency and accountability. Governments must ensure that decision-making mechanisms are open to public scrutiny, reducing the fertile ground for conspiracy theories. For example, publishing detailed policy justifications and holding regular town hall meetings can empower citizens to engage critically rather than react fearfully. Practical steps include mandating clear communication protocols for public officials and investing in media literacy programs to help citizens discern credible information from misinformation.

A comparative analysis reveals that democracies with robust checks and balances are better equipped to resist the corrosive effects of political paranoia. In countries like Germany, where independent judicial systems and strong civil society networks exist, paranoid narratives are less likely to dominate public discourse. Conversely, in nations with weaker institutions, such as Hungary under Viktor Orbán, paranoia has been weaponized to consolidate power, sidelining opposition and eroding democratic norms. This contrast underscores the importance of institutional resilience in safeguarding democratic decision-making.

Persuasively, it is crucial to recognize that political paranoia thrives in environments of uncertainty and polarization. Leaders who exploit fear for political gain often frame complex issues in binary terms, leaving little room for nuanced debate. To counter this, policymakers should adopt inclusive decision-making frameworks that incorporate diverse perspectives. For instance, participatory budgeting initiatives, as seen in Porto Alegre, Brazil, involve citizens directly in resource allocation, reducing feelings of alienation and mistrust. Such approaches not only enhance democratic legitimacy but also dilute the appeal of paranoid narratives.

Finally, a descriptive lens highlights how political paranoia can manifest in everyday democratic practices. Public debates become polarized, with participants retreating into ideological echo chambers. Social media amplifies this effect, as algorithms prioritize sensational content that reinforces existing fears. To address this, platforms must implement stricter content moderation policies and promote fact-checked information. Simultaneously, educational institutions should integrate critical thinking skills into curricula, equipping younger generations to navigate an increasingly complex information landscape. By doing so, democracies can build resilience against the destabilizing forces of political paranoia.

Political Machines: Unseen Benefits in Local Governance and Community Development

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political paranoia refers to an intense, often irrational fear or suspicion that individuals, groups, or governments are conspiring to cause harm, undermine stability, or seize power. It can manifest in both individuals and societies, leading to mistrust, polarization, and sometimes extreme actions.

Political paranoia can stem from various factors, including historical traumas, economic instability, social inequality, misinformation, and manipulative political rhetoric. It often thrives in environments of uncertainty, fear, and lack of transparency.

Political paranoia can erode trust in institutions, deepen political divisions, and fuel extremism. It may lead to the scapegoating of certain groups, the suppression of dissent, and the undermining of democratic processes, ultimately destabilizing societies.

Yes, political paranoia can be mitigated through promoting media literacy, fostering open dialogue, strengthening democratic institutions, and addressing the root causes of fear and mistrust. Encouraging critical thinking and evidence-based reasoning is also crucial.