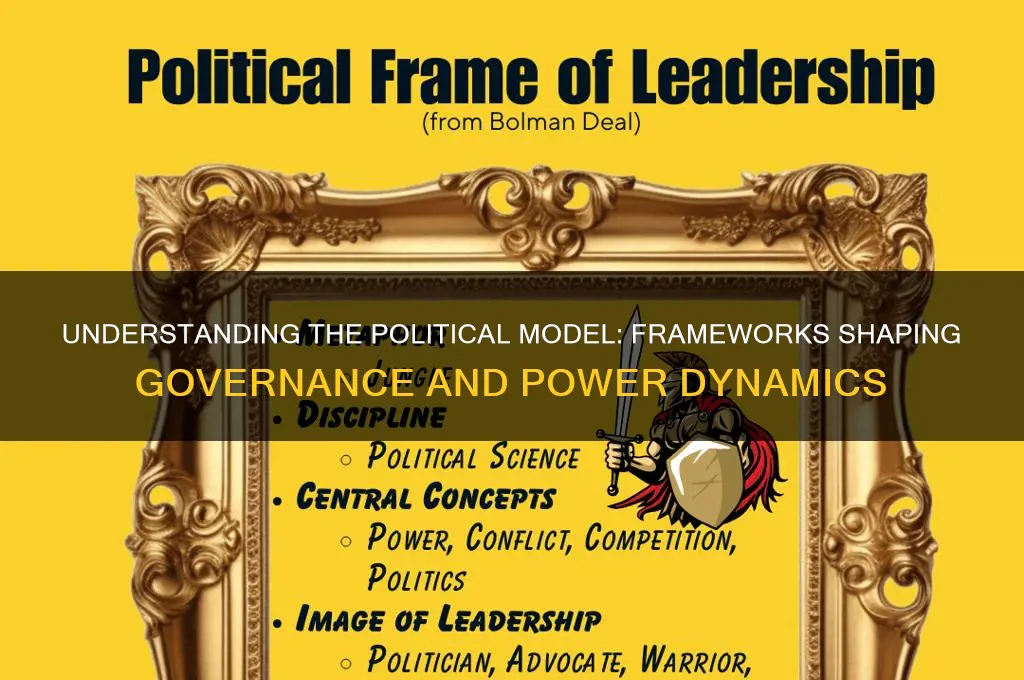

A political model is a conceptual framework or theoretical structure used to understand, analyze, and predict political systems, behaviors, and outcomes. It serves as a tool for scholars, policymakers, and analysts to interpret complex political phenomena by simplifying and organizing key elements such as power dynamics, institutions, ideologies, and decision-making processes. Political models can range from normative frameworks that prescribe ideal systems (e.g., democracy, authoritarianism) to empirical models that explain real-world political interactions. They often incorporate variables like governance structures, electoral systems, and societal influences to provide insights into how political systems function, evolve, and impact societies. By offering a systematic approach, political models facilitate comparative analysis, policy formulation, and the evaluation of political strategies across different contexts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A framework or theory that explains political processes, systems, or behaviors. |

| Purpose | To analyze, predict, and understand political phenomena. |

| Key Components | Actors (e.g., individuals, groups, institutions), structures, and processes. |

| Types | Normative (ideal systems), Empirical (observable realities), Explanatory (causal relationships). |

| Examples | Democratic model, Authoritarian model, Pluralist model, Elite theory. |

| Focus | Power distribution, decision-making, conflict resolution, governance. |

| Methodology | Qualitative (case studies, interviews) and Quantitative (statistical analysis). |

| Scope | Local, national, or global political systems. |

| Assumptions | Varies by model (e.g., rational actors, power maximization). |

| Criticisms | Over-simplification, bias, lack of universality, and limited predictive power. |

| Applications | Policy-making, political strategy, academic research, and education. |

| Evolution | Adapts to changing political landscapes (e.g., globalization, technology). |

| Interdisciplinary Links | Economics, sociology, psychology, and history. |

Explore related products

$34.97 $64.99

What You'll Learn

- Democracy: System of government by the people, either directly or through elected representatives

- Authoritarianism: Centralized power with limited political freedoms and opposition suppression

- Federalism: Division of power between national and regional governments, ensuring shared authority

- Totalitarianism: Extreme authoritarianism controlling all aspects of public and private life

- Anarchy: Absence of formal government, advocating self-governance and voluntary association

Democracy: System of government by the people, either directly or through elected representatives

Democracy, as a political model, hinges on the principle of governance by the people, either directly or through elected representatives. This system contrasts sharply with autocracies, where power is concentrated in the hands of a single individual or a small group. In a democratic framework, citizens participate in decision-making processes, ensuring that government actions reflect the collective will of the populace. This participation can take various forms, from voting in elections to engaging in public consultations, making democracy a dynamic and inclusive model of governance.

Direct democracy, though less common, allows citizens to propose, debate, and vote on laws directly. Switzerland is a notable example, where referendums are a regular feature of the political landscape. Citizens can challenge laws or propose new ones, fostering a high level of civic engagement. However, direct democracy is often limited to smaller jurisdictions due to logistical challenges in larger populations. For instance, organizing a nationwide vote on every issue would be impractical in a country like India, with its vast and diverse population.

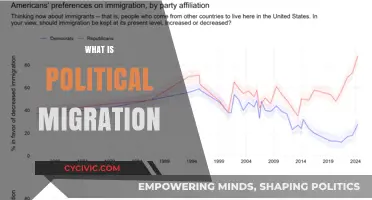

Representative democracy, the more prevalent form, involves electing officials to make decisions on behalf of the people. This model is scalable and practical for large nations. The United States, for example, operates as a representative democracy, where citizens elect members of Congress and the President to govern. This system relies on the accountability of elected officials to their constituents, typically through periodic elections. However, critics argue that it can lead to a disconnect between representatives and the people, especially if elected officials prioritize party interests over public opinion.

A critical aspect of democracy is the protection of minority rights. While majority rule is a cornerstone, democratic systems must include safeguards to prevent the tyranny of the majority. Constitutional limits, independent judiciaries, and robust civil liberties are essential components. For instance, the U.S. Bill of Rights ensures that certain fundamental freedoms are protected, regardless of popular sentiment. This balance is crucial for maintaining a just and equitable society within a democratic framework.

Implementing democracy effectively requires more than just elections; it demands an informed and engaged citizenry. Education plays a pivotal role in fostering political literacy, enabling citizens to make informed decisions. Practical tips for enhancing democratic participation include organizing community forums, promoting media literacy to combat misinformation, and encouraging youth involvement through school programs. For example, countries like Estonia have integrated digital tools into their democratic processes, allowing citizens to vote online and access government services transparently. Such innovations can strengthen democratic institutions by making them more accessible and responsive to the needs of the people.

Are Mimes Politically Incorrect? Exploring the Debate and Its Implications

You may want to see also

Authoritarianism: Centralized power with limited political freedoms and opposition suppression

Authoritarianism thrives on the concentration of power in a single entity—be it an individual, a party, or a junta—with minimal checks and balances. This model systematically curtails political freedoms, such as free speech, assembly, and the press, to maintain control. Opposition is not merely discouraged but actively suppressed through censorship, surveillance, and often, state-sanctioned violence. Examples like North Korea’s Kim regime or Belarus under Lukashenko illustrate how authoritarian systems prioritize stability over individual rights, often at the cost of societal innovation and dissent.

To understand authoritarianism’s mechanics, consider its operational playbook. First, it centralizes decision-making, eliminating power-sharing mechanisms. Second, it cultivates a culture of fear through security apparatuses like secret police or propaganda machines. Third, it co-opts institutions—courts, media, and elections—to serve the ruling authority rather than the public. For instance, Russia’s electoral system under Putin nominally holds votes but ensures outcomes favor the incumbent through voter intimidation and ballot manipulation. This blueprint ensures longevity but stifles genuine political competition.

A persuasive argument against authoritarianism lies in its inherent fragility. While it promises order, it often breeds corruption, inefficiency, and economic stagnation due to the absence of accountability. Citizens may comply outwardly but harbor resentment, as seen in Iran’s Green Movement or Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests. Moreover, the suppression of opposition does not eliminate dissent—it drives it underground, fostering radicalization. History shows that such regimes collapse dramatically when internal contradictions or external pressures overwhelm their control mechanisms, as in the fall of the Soviet Union or Mubarak’s Egypt.

Comparatively, authoritarianism contrasts sharply with democratic models, which distribute power and protect civil liberties. However, it shares similarities with technocratic or paternalistic systems in its claim to superior decision-making. The key difference lies in authoritarianism’s rejection of pluralism and its reliance on coercion. While democracies address opposition through dialogue and compromise, authoritarian regimes view it as a threat to be eradicated. This zero-sum approach undermines long-term stability, as evidenced by Syria’s civil war, triggered by Assad’s brutal crackdown on peaceful protests.

For those studying or confronting authoritarianism, practical insights are crucial. First, recognize its adaptability—modern authoritarians often cloak repression in legal frameworks or exploit digital tools for surveillance. Second, focus on grassroots resistance networks, which leverage decentralized communication to evade detection. Third, international pressure, such as sanctions or diplomatic isolation, can weaken authoritarian regimes but must be coupled with support for local civil society. Finally, document human rights abuses meticulously; evidence becomes a weapon in the fight for accountability, as seen in the Nuremberg Trials or the International Criminal Court’s investigations into authoritarian leaders.

Is Carey Hart Political? Uncovering His Views and Stances

You may want to see also

Federalism: Division of power between national and regional governments, ensuring shared authority

Federalism is a political model that divides power between a central national government and regional governments, such as states or provinces. This system ensures shared authority, allowing both levels to operate independently within their designated spheres while also collaborating on matters of mutual interest. For instance, in the United States, the federal government handles national defense and foreign policy, while state governments manage education and local infrastructure. This division prevents the concentration of power, fostering a balance that protects individual liberties and accommodates regional diversity.

Consider the practical implementation of federalism in countries like Germany or India. In Germany, the Basic Law outlines the responsibilities of the federal and state governments, ensuring clarity and minimizing conflicts. States like Bavaria retain significant autonomy in cultural and educational policies, reflecting local preferences. Similarly, India’s federal structure allows states like Tamil Nadu to implement unique welfare programs, such as free healthcare initiatives, tailored to their populations. These examples illustrate how federalism enables localized decision-making while maintaining national unity.

However, federalism is not without challenges. The division of power can lead to jurisdictional disputes, as seen in the U.S. debates over healthcare or environmental regulations. Regional governments may resist federal policies they perceive as infringing on their autonomy, creating gridlock. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, differing state and federal responses in the U.S. highlighted the complexities of coordinating efforts in a federal system. Effective federalism requires robust mechanisms for intergovernmental cooperation, such as joint councils or shared funding programs, to address these challenges.

To implement federalism successfully, policymakers must prioritize clarity in constitutional frameworks. Define the powers of each level of government explicitly, leaving minimal room for ambiguity. Encourage regular dialogue between national and regional authorities through formal platforms like federal-state commissions. Additionally, allocate resources equitably to ensure regional governments can fulfill their responsibilities without over-reliance on the center. For example, Switzerland’s system of cantons exemplifies this balance, with cantons retaining significant fiscal autonomy while contributing to federal initiatives.

In conclusion, federalism offers a dynamic political model for managing diverse societies by distributing power between national and regional governments. Its strength lies in its ability to combine unity with diversity, but its success depends on careful design and ongoing cooperation. By studying examples like the U.S., Germany, and India, nations can tailor federal systems to their unique contexts, ensuring shared authority remains a tool for stability and progress.

Mastering the Art of Catching Politoed: Tips and Strategies

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Totalitarianism: Extreme authoritarianism controlling all aspects of public and private life

Totalitarianism represents the apex of political control, where the state infiltrates every facet of existence, leaving no room for individual autonomy or dissent. Unlike authoritarian regimes that primarily focus on political power, totalitarian systems seek to dominate culture, ideology, and personal life. This model is characterized by a single, often charismatic leader or party that wields absolute authority, employing propaganda, surveillance, and repression to maintain dominance. Examples include Nazi Germany, Stalinist Soviet Union, and modern-day North Korea, where the state’s reach extends into family dynamics, religious beliefs, and even personal thoughts. The goal is not merely compliance but the complete transformation of society into a monolithic entity aligned with the regime’s vision.

To understand totalitarianism, consider its operational mechanisms. First, it relies on a pervasive ideology that justifies its existence and demands unwavering loyalty. Second, it employs a vast apparatus of control, including secret police and informants, to monitor and punish deviation. Third, it monopolizes information through censorship and state-controlled media, shaping public perception and suppressing alternative narratives. For instance, in Orwell’s *1984*, the Party’s slogan “Big Brother is watching you” encapsulates the psychological and physical surveillance inherent in such systems. Practically, this means citizens must self-censor, constantly aligning their actions and thoughts with the state’s expectations to avoid retribution.

A critical takeaway is that totalitarianism thrives on the erasure of boundaries between public and private life. It demands not just obedience but enthusiasm, often through mass mobilization and public displays of loyalty. For individuals living under such regimes, survival requires navigating a minefield of unspoken rules and constant vigilance. A practical tip for understanding its impact: examine how totalitarian states manipulate language, as seen in Newspeak from *1984*, where vocabulary is restricted to limit free thought. This linguistic control is a microcosm of the broader suppression of individuality and dissent.

Comparatively, while authoritarian regimes may restrict political freedoms, they rarely attempt to control personal beliefs or private life to the same extent. Totalitarianism, however, seeks to reshape humanity itself, often through extreme measures like re-education camps or forced labor. For instance, Mao’s Cultural Revolution in China targeted intellectuals and traditional culture, aiming to create a new, ideologically pure society. This distinction highlights the unique danger of totalitarianism: its ambition to redefine reality itself, leaving no space for resistance or alternative identities.

In conclusion, totalitarianism is not merely a political model but a comprehensive system of domination that permeates every aspect of human existence. Its success hinges on the total subjugation of individual will to the collective ideology of the state. For those studying or confronting such systems, recognizing its mechanisms—ideological indoctrination, surveillance, and cultural homogenization—is crucial. While it promises stability and unity, the cost is the loss of freedom, diversity, and humanity itself. Understanding totalitarianism serves as a cautionary tale, reminding us of the fragility of liberty and the importance of safeguarding democratic values.

Narendra Modi's Political Journey: From RSS to Prime Minister

You may want to see also

Anarchy: Absence of formal government, advocating self-governance and voluntary association

Anarchy, often misunderstood as chaos, is fundamentally about the absence of formal government, emphasizing self-governance and voluntary association. This political model challenges the traditional hierarchy of state authority, proposing instead a society where individuals and communities organize themselves without coercive institutions. At its core, anarchy is not the absence of order but the rejection of imposed order, advocating for structures that emerge organically from mutual agreement and cooperation.

Consider the practical implications of self-governance. In an anarchist framework, decision-making shifts from centralized authorities to local, voluntary collectives. For instance, communities might establish consensus-based assemblies where every voice carries equal weight, ensuring that power remains decentralized. This approach fosters direct participation in political processes, eliminating the alienation often experienced in representative democracies. However, it requires a high degree of engagement and trust among participants, as well as mechanisms to resolve conflicts without resorting to external authority.

Voluntary association is another cornerstone of anarchy, allowing individuals to form and dissolve groups based on shared interests or goals. This principle extends to economic systems, where cooperatives and mutual aid networks replace hierarchical corporations. For example, worker cooperatives operate on the basis of equal ownership and democratic management, ensuring that profits and decision-making power are distributed fairly. Such models demonstrate that economic efficiency and equity can coexist without state intervention, though they demand active participation and a commitment to collective well-being.

Critics often argue that anarchy is impractical, pointing to the potential for power vacuums or the exploitation of weaker individuals. However, historical and contemporary examples challenge this view. The Spanish Revolution of 1936 saw anarchist principles implemented on a large scale, with worker-controlled factories and agrarian collectives thriving despite external threats. Similarly, modern movements like the Zapatistas in Mexico and Rojava in Syria illustrate how self-governance can function effectively, even in adversarial conditions. These cases highlight the resilience of anarchist ideals when rooted in community solidarity and shared purpose.

Implementing anarchy requires a shift in mindset, from reliance on external authority to trust in collective capacity. It is not a quick fix but a long-term process of building institutions that reflect the values of autonomy and mutual aid. For those interested in exploring this model, start small: join or form cooperatives, participate in local decision-making forums, and support initiatives that prioritize voluntary association. By doing so, individuals can contribute to the gradual transformation of societal structures, moving toward a more equitable and self-governing world. Anarchy, in this sense, is not an end state but a continuous practice of freedom and responsibility.

Is 'In the Heights' a Political Statement or Cultural Celebration?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political model is a theoretical framework or system used to describe, analyze, or predict political processes, structures, and behaviors. It often outlines how power is distributed, decisions are made, and governance operates within a society or organization.

Examples include democracy, authoritarianism, socialism, capitalism, federalism, and anarchism. Each model represents distinct principles, such as democracy emphasizing citizen participation, while authoritarianism centralizes power in a single authority.

Political models provide a structured way to understand and compare different systems of governance. They help analyze strengths, weaknesses, and outcomes of political structures, aiding in policy-making, reforms, and debates about ideal forms of government.