Political migration refers to the movement of individuals or groups across borders, driven primarily by political factors such as persecution, conflict, human rights violations, or the lack of political freedoms in their home countries. Unlike economic migration, which is motivated by the search for better job opportunities or living conditions, political migrants flee to escape oppressive regimes, civil wars, or systemic discrimination. This type of migration often involves seeking asylum or refugee status in safer nations, where individuals hope to find protection and stability. Political migration is deeply intertwined with global politics, international law, and human rights, as it highlights the failures of states to protect their citizens and the responsibilities of the international community to provide refuge. Understanding political migration is crucial for addressing the root causes of displacement and developing policies that ensure the safety and dignity of those forced to leave their homes.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Movement of individuals or groups across borders due to political reasons. |

| Primary Causes | Political persecution, oppression, conflict, or instability. |

| Examples | Refugees fleeing authoritarian regimes, asylum seekers escaping war zones. |

| Legal Status | Often seek asylum or refugee status under international law (e.g., 1951 Refugee Convention). |

| Key Drivers | Human rights violations, political repression, civil unrest, or coups. |

| Global Trends (Latest) | Increasing numbers due to conflicts in regions like Ukraine, Afghanistan, and Myanmar. |

| Destination Countries | U.S., Germany, Canada, and other countries with robust asylum systems. |

| Challenges | Integration difficulties, legal barriers, and anti-immigrant sentiments. |

| International Frameworks | Governed by UNHCR, Geneva Convention, and regional agreements. |

| Recent Statistics (2023) | Over 108 million forcibly displaced people globally (UNHCR). |

| Impact on Host Countries | Economic contributions, cultural diversity, and potential social tensions. |

| Duration | Can be temporary or permanent, depending on political resolution in origin countries. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Economic Factors: Push-pull dynamics, job opportunities, poverty, and wealth disparities drive migration across borders

- Conflict and War: Displacement caused by violence, civil wars, and political instability forces people to flee

- Political Persecution: Individuals escape oppression, authoritarian regimes, and human rights violations in their home countries

- Policy and Legislation: Immigration laws, asylum policies, and government regulations shape migration patterns globally

- Climate and Environment: Political responses to climate change and environmental degradation influence migration trends

Economic Factors: Push-pull dynamics, job opportunities, poverty, and wealth disparities drive migration across borders

Economic disparities act as a powerful magnet, drawing individuals from regions of poverty toward areas of prosperity. Consider the stark contrast between a rural village in Guatemala, where daily wages average $5, and a bustling city like Los Angeles, where entry-level jobs start at $15 per hour. This wage gap, multiplied over months and years, creates an irresistible pull for those seeking to escape subsistence living. The push factor intensifies when local economies collapse due to drought, political instability, or lack of infrastructure, leaving migration as the only viable path to survival. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, where 40% of the population lives on less than $1.90 a day, the allure of higher wages in Europe or the Gulf states becomes a lifeline rather than a luxury.

Job opportunities abroad often serve as the primary pull factor, but their availability is not always guaranteed. Migrants frequently rely on informal networks—family, friends, or smugglers—to secure employment, which can lead to exploitation. In Dubai, for example, construction workers from South Asia are often promised high wages but end up in debt bondage, their passports confiscated by employers. To mitigate such risks, prospective migrants should verify job offers through official channels, such as government labor offices or international organizations like the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Additionally, learning basic legal rights in the destination country can empower migrants to negotiate fairer terms and avoid predatory schemes.

Poverty, however, is not merely a financial state but a systemic condition that limits access to education, healthcare, and social mobility. In Honduras, where 60% of the population lives below the poverty line, children often drop out of school by age 12 to work in fields or factories. This lack of education perpetuates the cycle of poverty, making migration seem like the only escape. Governments and NGOs can address this push factor by investing in vocational training programs tailored to local industries, such as agriculture or textiles, which provide skills that are both locally relevant and transferable abroad. For instance, a program in rural Mexico teaching sustainable farming techniques not only improves local livelihoods but also equips migrants with skills valued in countries like Canada or Australia.

Wealth disparities between nations further exacerbate migration pressures, particularly when global economic policies favor developed countries. Trade agreements like NAFTA have been criticized for undermining local economies in Mexico, leading to job losses in agriculture and manufacturing. Such policies create a dual push-pull dynamic: local industries collapse, pushing workers abroad, while multinational corporations in wealthier nations pull labor to fill low-wage positions. To counteract this, international trade agreements should include provisions for economic development in poorer countries, such as technology transfers or investment in local infrastructure. For individuals, understanding these global economic forces can help them make informed decisions about migration, balancing the promise of opportunity with the risks of exploitation.

Ultimately, economic migration is a rational response to irrational systems of inequality. While job opportunities and wealth disparities act as powerful pull factors, poverty and systemic failures serve as relentless push factors. Addressing these dynamics requires both individual strategies—such as verifying job offers and acquiring transferable skills—and systemic solutions, like fair trade policies and local economic development. By understanding these complexities, migrants can navigate the challenges of cross-border movement more effectively, while policymakers can create conditions that reduce the need for migration out of desperation.

Voltaire's Political Engagement: Satire, Philosophy, and Power Dynamics Explored

You may want to see also

Conflict and War: Displacement caused by violence, civil wars, and political instability forces people to flee

Violence, civil wars, and political instability have long been catalysts for human displacement, forcing millions to flee their homes in search of safety and stability. This form of migration, often referred to as forced migration, is a stark reminder of the profound impact that conflict can have on individuals and communities. The scale of displacement is staggering: according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), over 82 million people were forcibly displaced by the end of 2020, with conflict and persecution being the primary drivers. These numbers highlight the urgent need to understand and address the root causes of such displacement.

Consider the Syrian Civil War, which began in 2011 and has since become one of the most devastating conflicts of the 21st century. By 2023, more than 14 million Syrians—over half the country’s pre-war population—had been displaced, either internally or as refugees in neighboring countries like Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan. This crisis illustrates how prolonged violence not only destroys infrastructure and livelihoods but also tears apart social fabric, leaving families with no choice but to seek refuge elsewhere. The Syrian case is not unique; similar patterns of displacement have been observed in Afghanistan, South Sudan, and Yemen, where civil wars and political instability have created cycles of violence and exodus.

Analyzing the mechanics of displacement reveals a complex interplay of factors. Conflict often begins with political grievances, economic inequalities, or ethnic tensions, which escalate into armed violence when left unaddressed. As fighting intensifies, civilians face direct threats to their lives, loss of access to essential services, and destruction of property. For instance, in urban areas under siege, food and water shortages become critical within weeks, forcing residents to flee. Rural populations, though less densely packed, are equally vulnerable, as armed groups often target agricultural resources, disrupting livelihoods and food security. The decision to leave is rarely voluntary; it is a survival strategy in the face of imminent danger.

To mitigate the impact of conflict-induced displacement, international and local responses must be multifaceted. Humanitarian aid, including food, shelter, and medical care, is immediate and essential. However, long-term solutions require addressing the root causes of conflict through diplomacy, peacebuilding, and political reconciliation. For example, in Colombia, the 2016 peace agreement between the government and FARC rebels led to a significant reduction in violence and displacement, though challenges remain. Additionally, host countries and the international community must share responsibility for refugees, ensuring they have access to education, employment, and legal protection. Without such measures, displaced populations risk becoming trapped in cycles of poverty and marginalization.

Finally, it is crucial to recognize the resilience and agency of those displaced by conflict. While they are often portrayed as passive victims, many refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) actively contribute to their host communities and work toward rebuilding their lives. Policies and programs should empower these individuals, providing them with opportunities to participate in decision-making processes and access resources that enable self-sufficiency. By shifting the narrative from vulnerability to resilience, we can foster greater empathy and support for those forced to flee, ultimately working toward a world where displacement is no longer a necessary escape from violence and instability.

Do Artifacts Have Politics? Exploring Technology's Hidden Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Political Persecution: Individuals escape oppression, authoritarian regimes, and human rights violations in their home countries

Political persecution drives millions to flee their homelands annually, seeking refuge from systemic oppression, authoritarian regimes, and egregious human rights violations. Unlike economic migrants, who primarily seek better opportunities, these individuals face imminent threats to their safety, freedom, or life due to their political beliefs, affiliations, or identities. For example, in countries like Syria, Venezuela, and Afghanistan, dissenters, journalists, and minority groups often become targets of state-sanctioned violence, arbitrary detention, or extrajudicial killings. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reports that over 80% of refugees worldwide originate from nations with severe political repression, underscoring the urgency of this global crisis.

To understand the mechanics of political persecution, consider the case of journalists in authoritarian states. In countries like Belarus or Myanmar, reporters who expose government corruption or human rights abuses face harassment, imprisonment, or even assassination. For instance, following the 2021 military coup in Myanmar, over 100 journalists were detained, and independent media outlets were forcibly shut down. Such targeted attacks on free speech create an environment where staying becomes a death sentence, leaving migration as the only viable option for survival. Practical steps for at-risk individuals include documenting evidence of persecution, maintaining low digital profiles, and contacting international organizations like Reporters Without Borders for emergency assistance.

Persuasively, it’s critical to recognize that political persecution isn’t confined to high-profile activists or dissidents. Ordinary citizens, such as teachers advocating for educational reform or students participating in peaceful protests, can also become targets. In Nicaragua, for example, the Ortega regime has labeled university students as "terrorists" for opposing government policies, leading to mass arrests and forced exile. This broadening of persecution criteria means that anyone perceived as a threat to the regime’s power is vulnerable. For those in such situations, creating a contingency plan—including securing essential documents, identifying safe routes, and establishing contacts in host countries—can be lifesaving.

Comparatively, the experiences of political migrants differ significantly from those fleeing conflict or natural disasters. While all refugees face challenges, political migrants often carry the additional burden of psychological trauma from targeted persecution. Studies show that survivors of political repression exhibit higher rates of PTSD, anxiety, and depression compared to other refugee groups. This underscores the need for specialized mental health support in resettlement programs. Host countries can improve integration by offering trauma-informed care, legal aid for asylum applications, and community networks that foster solidarity among political exiles.

Descriptively, the journey of a political migrant is fraught with peril and uncertainty. Imagine a family in Eritrea, where indefinite military conscription and forced labor are commonplace. After a son deserts the army to avoid complicity in human rights abuses, the entire family becomes a target of state retribution. They must navigate treacherous borders, relying on smugglers and risking detention in transit countries. Upon reaching a safe nation, they face the daunting task of proving their persecution to asylum officials, often with limited evidence. Their story is not unique but emblematic of the resilience and desperation that define political migration. For those assisting such individuals, providing practical resources like language classes, legal representation, and access to humanitarian visas can make a profound difference.

Assessing Africa's Political Stability: Challenges, Progress, and Future Prospects

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$41.79 $54.99

Policy and Legislation: Immigration laws, asylum policies, and government regulations shape migration patterns globally

Immigration laws, asylum policies, and government regulations are the invisible architects of global migration patterns, often determining who moves, where they go, and under what conditions. These frameworks are not neutral; they reflect a nation’s priorities, values, and political climate. For instance, the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act in the United States shifted from a nationality-based quota system to one favoring skilled workers and family reunification, fundamentally altering the demographic makeup of the country. Such policies create pathways—or barriers—that shape the flow of people across borders, often with long-lasting consequences.

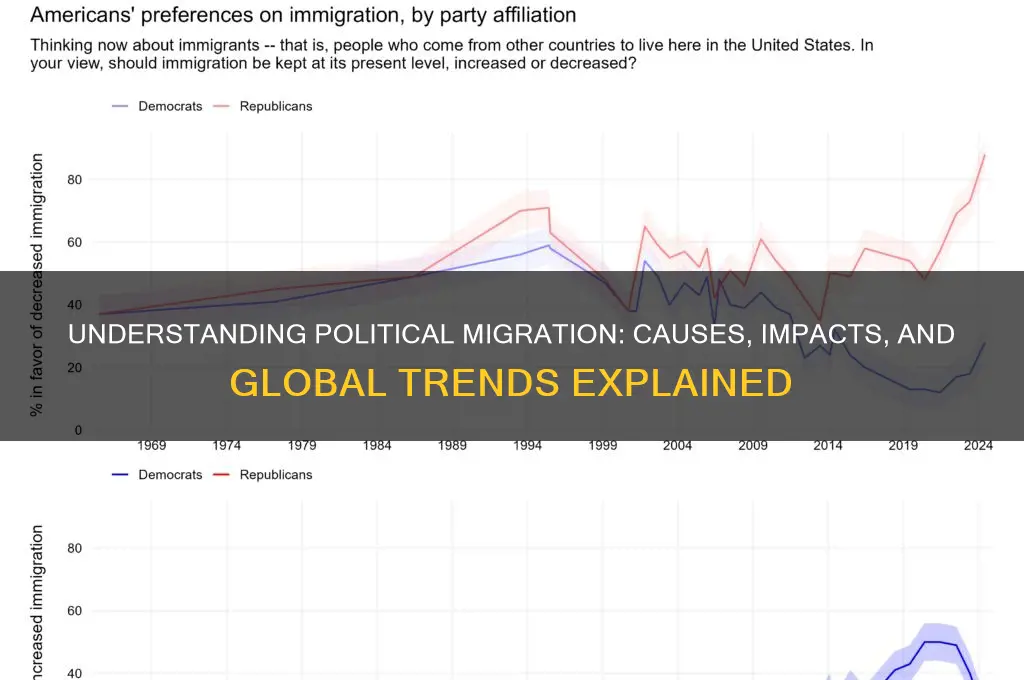

Consider the role of asylum policies in political migration. In theory, asylum is a humanitarian tool to protect individuals fleeing persecution. In practice, its application varies widely. Germany’s open-door policy during the 2015 refugee crisis admitted over a million asylum seekers, while countries like Hungary erected physical and legal barriers to deter them. These contrasting approaches highlight how policy decisions directly influence migration routes and volumes. Asylum seekers often become pawns in political games, their fates determined by shifting regulations rather than consistent international standards.

Government regulations also play a pivotal role in shaping migration by dictating the terms of entry, stay, and integration. For example, Canada’s point-based immigration system prioritizes education, language proficiency, and work experience, attracting a highly skilled workforce. Conversely, temporary worker programs in Gulf countries like Qatar tie visas to specific employers, creating vulnerabilities for migrant laborers. These regulatory frameworks not only control migration but also embed power dynamics that can exploit or empower migrants, depending on their design and enforcement.

The interplay between policy and migration is further complicated by global trends such as climate change and economic inequality. Nations increasingly face pressure to adapt their immigration laws to address these challenges. For instance, the European Union’s Blue Card scheme aims to attract highly skilled workers, while some Pacific Island nations are negotiating migration agreements as a response to rising sea levels. These policies demonstrate how governments proactively or reactively use legislation to manage migration in an interconnected world.

Ultimately, the impact of policy and legislation on migration is profound but not deterministic. While laws and regulations shape opportunities and constraints, individuals and communities find ways to navigate, resist, or exploit these frameworks. Policymakers must balance national interests with humanitarian obligations, ensuring that migration policies are both effective and just. As migration continues to evolve, so too must the policies that govern it, reflecting the complexities of a globalized society.

Effective Ways to Advocate and Support Your Political Cause

You may want to see also

Climate and Environment: Political responses to climate change and environmental degradation influence migration trends

Political responses to climate change and environmental degradation are reshaping migration patterns globally, often in ways that exacerbate existing inequalities. Consider the Pacific Island nations, where rising sea levels threaten entire communities. Governments in these regions face a stark choice: invest in costly adaptation measures or facilitate the relocation of their populations. Tuvalu, for instance, has negotiated agreements with countries like Australia and New Zealand to accept its citizens as climate refugees. This example illustrates how political decisions—whether proactive or reactive—directly influence migration flows. When states fail to address environmental challenges domestically, they effectively export their problems, turning climate change into a transnational political issue.

To understand this dynamic, examine the role of policy frameworks in either mitigating or accelerating migration. Countries with robust environmental policies, such as Germany’s Energiewende (energy transition), aim to reduce carbon emissions and minimize displacement. Conversely, nations prioritizing extractive industries, like Brazil’s deforestation policies under certain administrations, contribute to environmental degradation, forcing rural populations to migrate to urban centers or abroad. Policymakers must balance economic interests with long-term sustainability, recognizing that their decisions have ripple effects on migration trends. For instance, subsidies for fossil fuels in India perpetuate environmental harm, indirectly fueling migration from drought-prone regions.

A comparative analysis reveals that political responses to climate change often reflect power disparities. Wealthier nations, historically the largest emitters, frequently adopt measures that shift the burden onto developing countries. The European Union’s Green Deal, while ambitious, does little to address the immediate needs of climate-vulnerable states in Africa or Asia. Meanwhile, initiatives like the African Union’s Great Green Wall aim to combat desertification and reduce migration but lack sufficient international funding. This imbalance underscores the need for equitable global cooperation, where political responses prioritize both prevention and support for those already displaced.

Practical steps for policymakers include integrating climate migration into national and international strategies. For example, the United Nations’ Global Compact for Migration encourages states to recognize environmental migrants, though it remains non-binding. Governments can also invest in early warning systems and resilient infrastructure to reduce displacement. At the local level, community-based adaptation projects, such as mangrove restoration in Vietnam, empower residents to stay in place. However, caution is necessary: poorly designed policies, like forced resettlement programs, can lead to human rights violations. The key is to approach climate migration as a political responsibility, not merely a humanitarian issue.

Ultimately, the interplay between climate change, environmental degradation, and political responses demands a nuanced understanding of migration as a political act. As ecosystems collapse and resources dwindle, migration becomes both a survival strategy and a critique of policy failures. Whether through proactive adaptation, international cooperation, or local empowerment, political decisions will determine whether migration is a crisis or a managed transition. The challenge lies in aligning short-term political interests with the long-term survival of communities, ensuring that migration is a choice, not a necessity.

Hate Crimes as Political Tools: Power, Division, and Social Control

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political migration refers to the movement of individuals or groups across borders due to political reasons, such as persecution, conflict, oppression, or a lack of political freedoms in their home country.

The main causes include political persecution, human rights violations, civil wars, authoritarian regimes, and the suppression of political dissent or minority groups.

Political migration is driven by political factors like safety and freedom, while economic migration is motivated by the search for better job opportunities, higher income, or improved living standards.

Examples include the exodus of Cuban refugees during the 1980 Mariel boatlift, the migration of Vietnamese "boat people" after the Vietnam War, and the Syrian refugee crisis caused by the ongoing civil war.

Political migrants, particularly refugees, are protected under the 1951 Refugee Convention, which grants them the right to seek asylum, prohibits refoulement (returning them to danger), and ensures basic human rights in their host country.