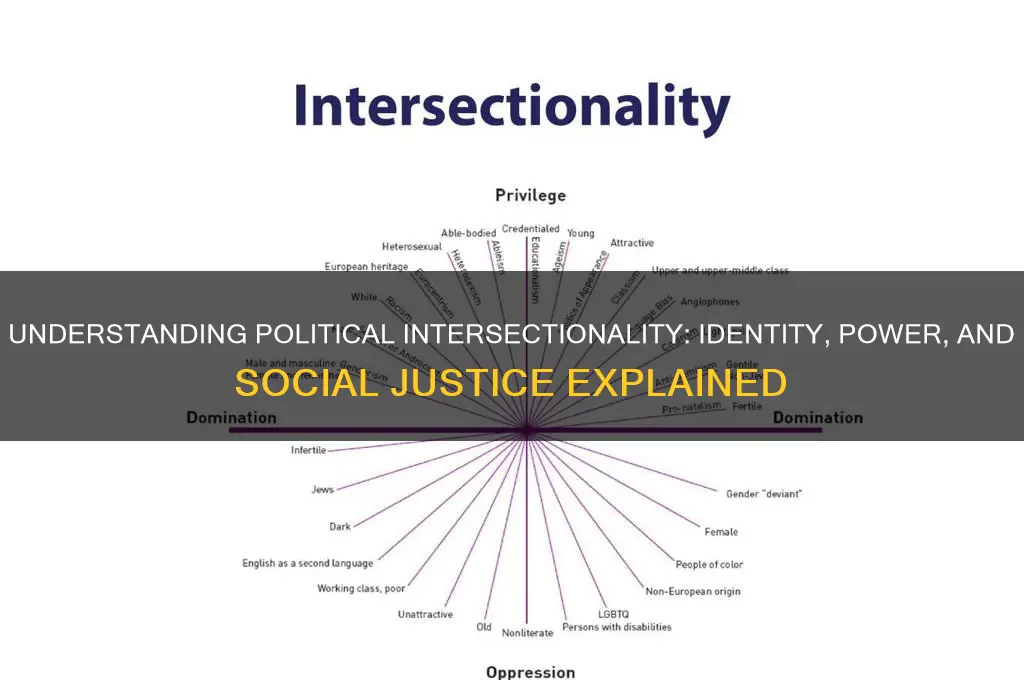

Political intersectionality refers to the examination of how various social and political identities—such as race, gender, class, sexuality, and disability—intersect and influence individuals' experiences within political systems. Rooted in Kimberlé Crenshaw's framework of intersectionality, this concept highlights how overlapping forms of oppression or privilege shape access to power, representation, and policy outcomes. In politics, intersectionality critiques traditional approaches that often address issues in isolation, advocating instead for a holistic understanding of how multiple identities compound or mitigate political marginalization. By centering the experiences of those at the margins, political intersectionality seeks to create more inclusive and equitable policies that address the complex realities of diverse populations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The interconnected nature of social categorizations (e.g., race, class, gender) in shaping political experiences and power structures. |

| Origin | Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, rooted in critical race theory and feminist thought. |

| Key Focus | How multiple identities (e.g., race, gender, class) intersect to create unique forms of discrimination and privilege. |

| Political Application | Analyzes how policies and systems disproportionately impact marginalized groups at the intersection of identities. |

| Examples | Black women facing discrimination that is both racist and sexist, distinct from experiences of Black men or white women. |

| Global Relevance | Applied to understand political inequalities across cultures, e.g., caste, religion, and ethnicity. |

| Criticisms | Accusations of overcomplicating analysis or neglecting class-based oppression in favor of identity politics. |

| Contemporary Issues | Used in discussions of police brutality, healthcare disparities, and climate justice through an intersectional lens. |

| Policy Impact | Advocates for inclusive policies addressing overlapping systems of oppression, not single-axis issues. |

| Academic Disciplines | Widely studied in political science, sociology, gender studies, and law. |

| Activism | Central to movements like Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ+ rights, and feminist activism. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins and Definition: Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, defines overlapping identities' impact on discrimination and political experiences

- Identity Politics: Examines how race, gender, class, and sexuality intersect in political representation and policies

- Policy Implications: Advocates for inclusive policies addressing multiple forms of oppression simultaneously in political systems

- Global Perspectives: Explores how intersectionality varies across cultures and political landscapes worldwide

- Activism and Movements: Highlights intersectionality's role in shaping diverse political movements and advocacy efforts

Origins and Definition: Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, defines overlapping identities' impact on discrimination and political experiences

The term "intersectionality" was first introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, as a way to describe the complex, cumulative manner in which social identities – such as race, gender, class, and sexuality – intersect and contribute to unique experiences of discrimination. Crenshaw, a prominent legal scholar and civil rights advocate, developed this concept to address the limitations of single-axis frameworks in understanding oppression. For instance, a Black woman cannot be fully understood through the lens of either racial or gender discrimination alone; her experiences are shaped by the interplay of these identities. This insight has since become a cornerstone in feminist, critical race, and social justice theories, offering a more nuanced approach to analyzing power dynamics and inequality.

To illustrate, consider the case of employment discrimination. A Black woman might face biases that are distinct from those experienced by either Black men or white women. Her race and gender intersect to create a specific set of challenges, such as being overlooked for promotions or facing stereotypes that neither group alone encounters. Crenshaw’s framework encourages us to examine these overlapping identities, rather than treating them as separate or hierarchical. This approach is not just theoretical; it has practical implications for policy-making, legal strategies, and social movements, ensuring that interventions are tailored to address the multifaceted nature of discrimination.

Applying intersectionality in political contexts requires a deliberate shift in perspective. It demands that we move beyond broad categories and instead focus on the individual and collective experiences of marginalized groups. For example, when analyzing voter suppression, an intersectional lens reveals how race, age, and socioeconomic status combine to disproportionately affect young, low-income voters of color. This specificity allows for more targeted advocacy and solutions. A practical tip for activists and policymakers is to conduct disaggregated data analysis, breaking down statistics by multiple demographic factors to uncover hidden patterns of exclusion.

However, implementing intersectionality is not without challenges. One caution is the risk of over-compartmentalizing identities, which can lead to a fragmented understanding of oppression. Another is the potential for intersectionality to be co-opted as a buzzword, stripped of its radical roots. To avoid these pitfalls, it’s essential to remain grounded in Crenshaw’s original intent: to amplify the voices and experiences of those most marginalized. This means actively centering the narratives of individuals who embody multiple oppressed identities in political discourse and decision-making processes.

In conclusion, Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality offers a transformative framework for understanding how overlapping identities shape political experiences and discrimination. By adopting this lens, we can move beyond one-size-fits-all approaches to justice and equity, instead crafting solutions that acknowledge and address the complexity of human lives. Whether in activism, policy, or everyday conversations, intersectionality serves as a powerful tool for dismantling systemic inequalities and fostering a more inclusive society.

Is Lisa Kudrow Involved in Politics? Exploring Her Political Views

You may want to see also

Identity Politics: Examines how race, gender, class, and sexuality intersect in political representation and policies

Political representation is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. Identity politics, a concept rooted in intersectionality, challenges the notion that experiences are universal. It argues that race, gender, class, and sexuality are not isolated categories but interconnected systems of power that shape an individual's political reality. A Black woman, for instance, doesn't experience discrimination solely as a woman or solely as a Black person; her experiences are uniquely shaped by the intersection of these identities.

Consider the fight for reproductive rights. A white, middle-class woman advocating for access to abortion may prioritize legal protections and healthcare coverage. However, a low-income woman of color might also face barriers like lack of transportation, language barriers, and a history of medical mistrust within her community. Identity politics highlights how these intersecting identities demand a more nuanced approach to policy solutions, addressing not just legal rights but also systemic inequalities.

This intersectional lens is crucial for understanding political representation. A legislature dominated by white, heterosexual men, regardless of their individual merits, inherently lacks the lived experiences to fully comprehend the needs of marginalized communities. Identity politics advocates for diverse representation, not as a tokenistic gesture, but as a necessary step towards creating policies that reflect the complexities of society. Imagine a healthcare policy debate where a transgender person of color is at the table. Their presence wouldn't just add a voice; it would bring a perspective shaped by experiences with healthcare discrimination, poverty, and systemic bias, leading to more comprehensive and equitable solutions.

However, identity politics is not without its critics. Some argue it can lead to fragmentation, pitting identity groups against each other. Others fear it prioritizes individual experiences over broader societal issues. These concerns are valid, but they shouldn't overshadow the power of intersectionality to expose hidden biases and advocate for a more just political system.

The key lies in recognizing that identity politics is not about division, but about understanding the complex web of power structures that shape our lives. It's about moving beyond a one-dimensional view of politics and embracing the richness of human experience. By acknowledging the intersections of race, gender, class, and sexuality, we can build a political landscape that truly represents and serves all its citizens.

Ending Relationships with Grace: A Guide to Breaking Up Politely

You may want to see also

Policy Implications: Advocates for inclusive policies addressing multiple forms of oppression simultaneously in political systems

Advocates for inclusive policies rooted in political intersectionality face a critical challenge: how to dismantle systemic oppression without reducing identities to a checklist. Simply acknowledging intersecting axes of power—race, gender, class, sexuality, ability—is insufficient. Effective policy must move beyond symbolic gestures to restructure institutions that perpetuate harm. For instance, a housing policy addressing racial discrimination must also account for gendered disparities in income and caregiving responsibilities, ensuring single mothers of color are not left behind. This requires a nuanced understanding of how oppressions compound, not just coexist.

Consider the following steps for crafting truly inclusive policies. First, center the voices of those most marginalized by the intersecting systems under scrutiny. This means actively involving disabled women of color, queer youth from low-income backgrounds, and other multiply-marginalized groups in policy design and implementation. Second, adopt a "both/and" approach rather than prioritizing one axis of oppression over another. For example, a healthcare policy targeting racial health disparities should simultaneously address LGBTQ+ health inequities, recognizing that Black trans individuals face unique barriers to care. Third, embed intersectional analysis into data collection and evaluation. Disaggregate data by race, gender, disability status, and other factors to reveal hidden disparities and measure policy impact across groups.

However, pitfalls abound. One common mistake is tokenistic inclusion, where marginalized voices are invited to the table but lack genuine decision-making power. Another is overlooking the specificity of experiences, such as assuming all women face the same challenges without accounting for how race, immigration status, or disability shape those experiences. Policymakers must also guard against policy silos, where efforts to address one form of oppression inadvertently exacerbate another. For example, a policy increasing police presence to address gender-based violence may disproportionately harm Black and brown communities already targeted by law enforcement.

The ultimate goal is not just to address multiple oppressions but to transform the systems that produce them. This requires a long-term commitment to structural change, such as overhauling education systems to eliminate racial and gender biases, or reforming healthcare to prioritize preventive care for marginalized communities. While this work is complex and often slow, the alternative—policies that perpetuate inequality under the guise of progress—is unacceptable. By embracing intersectionality, advocates can move beyond bandaid solutions to create policies that truly liberate all people.

Are Japanese Men Polite? Exploring Cultural Etiquette and Gender Norms

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Global Perspectives: Explores how intersectionality varies across cultures and political landscapes worldwide

Intersectionality, as a framework, reveals how overlapping identities—such as race, gender, class, and sexuality—shape experiences of oppression and privilege. When applied globally, its nuances shift dramatically across cultures and political landscapes, challenging the assumption of a one-size-fits-all approach. For instance, in India, caste intersects with gender in ways that render Dalit women uniquely vulnerable to violence and economic exploitation, a dynamic less prominent in Western intersectional discourse. This example underscores the necessity of contextualizing intersectionality to avoid erasing local complexities.

Consider the Middle East, where religious identity often intersects with gender and nationality in ways that defy Western feminist frameworks. In Iran, women’s resistance to compulsory hijab laws is both a gendered struggle and a political act against state control, yet it cannot be reduced to a universal fight for "liberation." Similarly, in Saudi Arabia, the recent lifting of the driving ban for women reflects progress but remains entangled with the monarchy’s geopolitical interests and global image management. These cases illustrate how intersectionality must account for regional power structures and cultural norms to remain relevant.

In Africa, intersectionality takes on yet another dimension, often centering on postcolonial legacies and resource distribution. In Kenya, for example, LGBTQ+ activists face not only homophobic laws but also accusations of promoting "Western decadence," highlighting how sexual identity intersects with neocolonial narratives. Meanwhile, in South Africa, the legacy of apartheid means race and class remain dominant axes of oppression, even as gender-based violence persists. Here, intersectionality demands a historical lens, recognizing how past injustices continue to shape present inequalities.

To apply intersectionality globally, practitioners must adopt a three-step approach: localize, contextualize, and collaborate. First, localize by identifying the specific identities and systems at play in a given region—for instance, focusing on indigeneity in Latin America or tribal identity in Southeast Asia. Second, contextualize by examining how these identities interact with local political, economic, and cultural forces. Finally, collaborate with grassroots movements and scholars from those regions to avoid imposing external frameworks. This method ensures intersectionality remains a tool for empowerment, not a blueprint for cultural imperialism.

A cautionary note: while globalizing intersectionality is necessary, it risks diluting its radical potential if not handled carefully. For example, Western academics often prioritize "universal" categories like gender and race, overlooking region-specific axes such as caste or tribal status. To avoid this pitfall, prioritize dosage values—allocate equal weight to local and global perspectives in analysis. For instance, when studying migration, consider how a Syrian refugee’s experience is shaped by nationality, religion, and gender, but also by the policies of host countries and global power dynamics. This balanced approach ensures intersectionality remains both nuanced and actionable across borders.

Mastering Polite Goodbyes: How to Hang Up Gracefully in Any Conversation

You may want to see also

Activism and Movements: Highlights intersectionality's role in shaping diverse political movements and advocacy efforts

Intersectionality, a framework that examines how overlapping identities such as race, gender, class, and sexuality create unique experiences of oppression or privilege, has become a cornerstone of modern activism. By recognizing these intersections, movements can address the multifaceted nature of systemic inequalities, ensuring that advocacy efforts are inclusive and effective. For instance, the Black Lives Matter movement explicitly centers the experiences of Black women and LGBTQ+ individuals, acknowledging that racism intersects with sexism and homophobia in ways that demand tailored strategies for justice.

To integrate intersectionality into activism, organizers must first conduct a thorough analysis of the communities they aim to serve. This involves identifying the specific challenges faced by different subgroups within a broader movement. For example, in climate justice campaigns, Indigenous women often bear the brunt of environmental degradation due to the intersection of colonialism, gender, and ecological exploitation. By amplifying their voices and incorporating their perspectives, movements can develop solutions that are both equitable and sustainable.

A practical step for activists is to adopt an intersectional lens in policy advocacy. This means pushing for legislation that addresses the compounded effects of discrimination. For instance, advocating for paid family leave must consider how low-wage workers, particularly women of color, are disproportionately affected by the lack of such policies. Crafting demands that explicitly account for these intersections ensures that no one is left behind in the pursuit of progress.

However, implementing intersectionality in activism is not without challenges. One common pitfall is tokenism, where marginalized voices are included superficially without genuine power-sharing. To avoid this, movements must prioritize leadership roles for individuals with intersecting identities and create spaces for them to shape strategies. Additionally, activists should be cautious of oversimplifying complex issues, as intersectionality requires nuanced understanding and continuous learning.

In conclusion, intersectionality is not merely a theoretical concept but a practical tool for transforming political movements. By centering the experiences of those most marginalized, activists can build coalitions that are resilient, inclusive, and capable of achieving lasting change. Whether through grassroots organizing or policy advocacy, the intersectional approach ensures that the fight for justice is as diverse and multifaceted as the people it seeks to empower.

Graceful Exits: Mastering the Art of Politely Ending Conversations

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political intersectionality is a framework that examines how multiple social identities (such as race, gender, class, sexuality, and disability) intersect and influence an individual's or group's experiences within political systems, policies, and power structures.

Intersectionality in politics highlights how overlapping identities shape political participation, representation, and outcomes. It critiques policies that fail to address the unique challenges faced by marginalized groups at the intersections of multiple identities.

Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality in 1989 to describe how Black women face unique discrimination at the intersection of racism and sexism. Politically, it applies by advocating for policies that address the compounded effects of multiple forms of oppression.

Intersectionality is crucial in political movements because it ensures inclusivity and addresses the diverse needs of all participants. It prevents the marginalization of certain groups within broader movements and fosters more equitable and effective activism.

Examples include policies that address the specific needs of LGBTQ+ people of color, women with disabilities, or low-income immigrants. These policies recognize how intersecting identities create unique barriers and tailor solutions accordingly.