Political institutionalism is a theoretical framework within political science that focuses on the role of formal and informal institutions in shaping political behavior, outcomes, and processes. It emphasizes how institutions—such as constitutions, legislatures, courts, and bureaucratic structures—structure interactions between political actors, influence decision-making, and stabilize or transform political systems. By examining the rules, norms, and procedures embedded in these institutions, political institutionalism seeks to explain how they facilitate cooperation, manage conflict, and distribute power within societies. This approach highlights the enduring impact of institutional design on governance, policy-making, and the overall functioning of political systems, offering insights into both stability and change in political environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Focus on Institutions | Emphasizes formal and informal rules, norms, and organizations as key drivers of political behavior. |

| Stability and Order | Institutions provide stability, predictability, and structure in political systems. |

| Rule-Based Behavior | Political actors are constrained and guided by institutional rules and norms. |

| Path Dependency | Historical institutional choices shape current political outcomes and limit future options. |

| Power Distribution | Institutions define how power is distributed, exercised, and contested among actors. |

| Formal vs. Informal Institutions | Recognizes both formal (e.g., laws, constitutions) and informal (e.g., customs, traditions) institutions. |

| Institutional Design | The design of institutions influences policy outcomes and political processes. |

| Institutional Change | Institutions are not static; they can evolve through gradual or abrupt changes. |

| Role of Actors | Political actors (e.g., parties, bureaucrats) operate within and are shaped by institutions. |

| Comparative Analysis | Often used to compare political systems and outcomes across different institutional contexts. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Formal Rules & Structures: Study of constitutions, laws, and organizations shaping political behavior and outcomes

- Informal Norms & Practices: Unwritten rules, traditions, and customs influencing political institutions

- Institutional Design: How institutions are structured and their impact on governance

- Path Dependency: Historical events and decisions shaping current institutional frameworks

- Institutional Change: Factors driving evolution or stability of political institutions over time

Formal Rules & Structures: Study of constitutions, laws, and organizations shaping political behavior and outcomes

Political institutionalism posits that formal rules and structures—constitutions, laws, and organizations—are the scaffolding of political behavior and outcomes. These frameworks do not merely reflect societal norms; they actively shape how power is distributed, decisions are made, and conflicts are resolved. For instance, a presidential system, as outlined in the U.S. Constitution, centralizes executive authority in a single figure, fostering a distinct political dynamic compared to the collective leadership of a parliamentary system like Germany’s. Such designs are not neutral; they embed incentives, constraints, and opportunities that guide actors’ choices, from legislative gridlock to policy innovation.

Consider the role of electoral laws in determining political landscapes. A first-past-the-post system, as used in the U.K., tends to produce two-party dominance by marginalizing smaller parties, while proportional representation, as in the Netherlands, encourages multi-party coalitions and minority representation. These rules are not just procedural; they dictate the feasibility of certain political strategies and the inclusivity of democratic processes. Similarly, the structure of federalism—whether power is concentrated in a central government or dispersed to states—influences policy uniformity, regional autonomy, and even the speed of crisis response, as seen in the varying COVID-19 strategies across U.S. states.

Organizations, too, are critical in this framework. Bureaucracies, courts, and legislative bodies are not passive implementers of policy but active interpreters with their own cultures, capacities, and interests. The U.S. Supreme Court, for example, has shaped civil rights through landmark rulings like *Brown v. Board of Education*, demonstrating how institutional design can either reinforce or challenge existing power structures. Similarly, the European Union’s complex decision-making processes, involving the Council, Parliament, and Commission, reflect a deliberate attempt to balance member states’ sovereignty with collective action, though often at the cost of efficiency.

To study these dynamics effectively, researchers must adopt a multi-method approach. Comparative analysis of constitutional designs across countries can reveal patterns in governance outcomes, while historical institutionalism traces how past decisions create path dependencies. For instance, the legacy of colonial-era legal systems in Africa continues to influence contemporary judicial independence and economic regulation. Practical tips for analysts include mapping institutional hierarchies, identifying veto points, and examining enforcement mechanisms, as even the most progressive laws fail without credible implementation.

Ultimately, understanding formal rules and structures requires recognizing their dual nature: they are both constraints and enablers. While they limit certain behaviors, they also create pathways for innovation and reform. Policymakers and reformers must therefore engage with these frameworks strategically, whether by amending constitutions, redesigning bureaucratic processes, or leveraging international organizations. The takeaway is clear: institutions are not just the backdrop of politics—they are its architects.

Mike Rowe's Political Views: Uncovering His Stance and Influence

You may want to see also

Informal Norms & Practices: Unwritten rules, traditions, and customs influencing political institutions

Informal norms and practices, though unwritten, form the invisible scaffolding of political institutions, often shaping behavior more profoundly than formal rules. Consider the U.S. Senate’s filibuster tradition, which, despite not being codified in law, has become a powerful tool for delaying or blocking legislation. This practice illustrates how customs can evolve into de facto rules, influencing institutional dynamics without ever being formally adopted. Such norms are not merely relics of history; they are living mechanisms that adapt to political contexts, sometimes reinforcing stability and other times perpetuating gridlock.

To understand their impact, dissect the role of informal norms in decision-making processes. For instance, in many parliamentary systems, the principle of cabinet solidarity—where ministers publicly support government decisions even if they privately disagree—is an unwritten rule. This norm ensures unity but can stifle dissent, highlighting the dual-edged nature of informal practices. They foster cohesion but may also suppress accountability. Analyzing these trade-offs reveals how informal norms act as both lubricants and constraints within institutions, often determining their efficiency and legitimacy.

A comparative lens further illuminates their significance. In Japan, the *nemawashi* practice—an informal consensus-building process—precedes formal decision-making, ensuring that proposals are widely accepted before being officially presented. Contrast this with the adversarial norms of the UK’s Prime Minister’s Questions, where public confrontation is the norm. These examples demonstrate how cultural contexts shape informal practices, which in turn mold institutional behavior. Such variations underscore the importance of understanding local customs when studying political institutions globally.

Practical engagement with informal norms requires a strategic approach. Policymakers and reformers must first map these unwritten rules, identifying their origins, enforcers, and consequences. For instance, in organizations with entrenched seniority norms, introducing merit-based promotions may face resistance unless accompanied by gradual cultural shifts. Similarly, transparency initiatives can inadvertently undermine trust if they clash with norms of confidentiality. The key is to align formal changes with informal expectations, ensuring reforms are not just imposed but integrated.

Ultimately, informal norms and practices are not peripheral to political institutionalism—they are its lifeblood. Ignoring them risks misinterpreting institutional behavior, while harnessing them can unlock pathways to meaningful change. Whether as barriers or enablers, these unwritten rules demand attention, offering a nuanced understanding of how power operates within and between institutions. Their study is not just academic; it is a practical guide to navigating the complexities of political systems.

Understanding Russia's Political System: Power, Parties, and Putin's Influence

You may want to see also

Institutional Design: How institutions are structured and their impact on governance

Institutions are the scaffolding of governance, shaping how power is exercised, policies are made, and societies function. Institutional design—the deliberate structuring of these frameworks—is not merely an academic exercise; it is a practical tool for achieving specific political, economic, or social outcomes. Consider the difference between a presidential system, where power is divided between an elected president and a legislature, and a parliamentary system, where the executive is drawn from and accountable to the legislature. The former often fosters checks and balances but can lead to gridlock, as seen in the U.S. Congress. The latter promotes decisiveness but risks concentration of power, as observed in the U.K.’s parliamentary dominance. These structural choices are not neutral; they embed incentives, constraints, and opportunities that dictate governance dynamics.

To design effective institutions, one must follow a systematic approach. Step one: Define the purpose. Is the goal to maximize accountability, ensure representation, or streamline decision-making? For instance, proportional representation systems aim to reflect the diversity of voter preferences, while first-past-the-post systems prioritize stable majorities. Step two: Align structure with function. A bicameral legislature, like the U.S. Senate and House, balances regional and population-based interests, but it can also slow down legislation. Step three: Anticipate unintended consequences. Decentralization may empower local communities but can also exacerbate regional inequalities if not paired with fiscal equalization mechanisms. Caution: Avoid over-engineering. Complex institutions, like South Africa’s hybrid executive system, can confuse citizens and dilute accountability.

The impact of institutional design is evident in real-world outcomes. Take the European Union, a unique supranational institution designed to prevent conflict through economic interdependence. Its complex decision-making processes, involving the European Commission, Council, and Parliament, ensure inclusivity but often result in slow responses to crises, as seen during the Eurozone debt crisis. In contrast, China’s centralized party-state system enables rapid policy implementation but limits political pluralism. These examples illustrate how design choices trade off efficiency, equity, and stability. Practical tip: When designing institutions, use pilot programs to test structures at a smaller scale before full implementation.

A persuasive argument for thoughtful institutional design lies in its ability to address societal challenges. For instance, gender quotas in legislatures, as implemented in Rwanda and Sweden, have significantly increased women’s representation, challenging patriarchal norms. Similarly, independent anti-corruption bodies, like Hong Kong’s ICAC, demonstrate how structural autonomy can enhance accountability. However, such designs must be context-specific. A one-size-fits-all approach, like imposing Western-style democracies in post-conflict societies, often fails due to cultural and historical mismatches. Takeaway: Institutional design is not a blueprint but a tailored solution, requiring deep understanding of local realities.

Finally, the longevity and adaptability of institutions are critical. Historical examples, such as the U.S. Constitution’s amendment process, show how flexibility can ensure relevance over centuries. In contrast, rigid institutions, like Venezuela’s centralized presidential system, can collapse under stress. Instruction: Build in mechanisms for adaptation, such as regular constitutional reviews or sunset clauses for new policies. Comparative insight: Federal systems, like Germany’s, balance unity and diversity by devolving power to states, while unitary systems, like France’s, prioritize centralized control. The choice depends on the nation’s size, diversity, and historical trajectory. In essence, institutional design is both art and science, demanding precision, foresight, and humility.

Fracking's Political Divide: Energy, Economy, and Environmental Debates Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$29.95 $29.95

Path Dependency: Historical events and decisions shaping current institutional frameworks

Political institutions, the rules and norms governing collective decision-making, are not born in a vacuum. They are the products of history, forged in the crucible of past events and decisions. This phenomenon, known as path dependency, highlights how seemingly insignificant choices or events can have profound and lasting consequences, locking societies into specific institutional trajectories.

Imagine a river carving its path through a landscape. The initial trickle of water, influenced by the slightest gradient, determines the river's course for miles. Similarly, early political decisions, often made under unique circumstances, can create "critical junctures" that shape the evolution of institutions. For instance, the decision to adopt a presidential versus a parliamentary system in a fledgling democracy can have ripple effects on political stability, power distribution, and policy outcomes for generations.

The American Civil War serves as a stark example. The war's outcome not only preserved the Union but also solidified the federal government's authority over states, a principle that continues to shape American politics today. This historical event created a path dependency, making it extremely difficult to revert to a weaker federal system.

Understanding path dependency is crucial for policymakers and reformers. It explains why institutional change is often incremental and resistant to radical shifts. Attempting to overhaul deeply entrenched institutions, shaped by decades or even centuries of path dependency, is akin to redirecting a mature river – a monumental task requiring immense effort and potentially causing significant disruption.

Recognizing the power of path dependency doesn't imply inevitability. While historical events cast long shadows, they don't dictate an unalterable future. Societies can, through deliberate and sustained effort, create new paths. However, such efforts require a deep understanding of the historical forces that have shaped existing institutions and a willingness to navigate the complexities of institutional inertia.

Consider the case of post-apartheid South Africa. The legacy of apartheid created a deeply unequal society with segregated institutions. Overcoming this path dependency required a conscious effort to dismantle discriminatory laws, promote affirmative action, and foster reconciliation. While the process is ongoing, South Africa's experience demonstrates that even the most entrenched institutional frameworks can be challenged and transformed, albeit with considerable time and effort.

Understanding the American Association of Political Science: Roles and Impact

You may want to see also

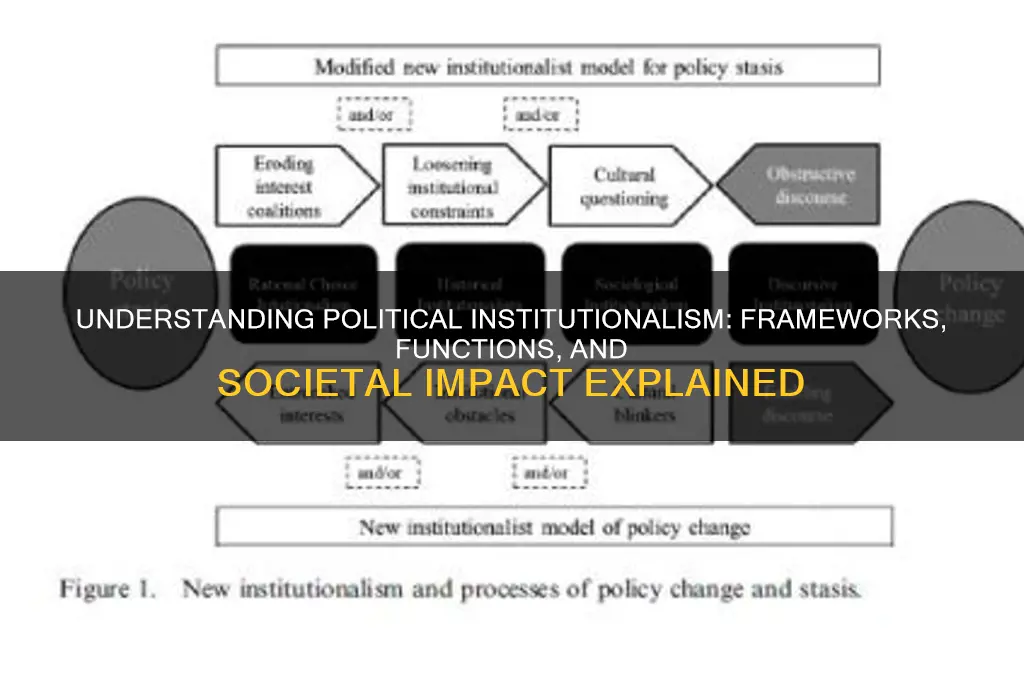

Institutional Change: Factors driving evolution or stability of political institutions over time

Political institutions, the formal and informal rules that structure political behavior, are not static entities. They evolve, adapt, or resist change in response to a complex interplay of factors. Understanding these drivers is crucial for predicting institutional trajectories and shaping political outcomes.

Historical Contingency and Path Dependence:

Imagine a country's electoral system, established decades ago, favoring a two-party structure. This initial design creates incentives for strategic voting and discourages smaller parties. Over time, this system becomes entrenched, making it difficult to transition to a proportional representation model, even if societal preferences shift. This illustrates path dependence, where past decisions constrain future choices, shaping institutional stability.

Historical events, like revolutions or economic crises, can act as critical junctures, creating windows of opportunity for significant institutional change. For instance, the collapse of the Soviet Union led to rapid institutional transformations in Eastern Europe, demonstrating how external shocks can disrupt established institutional equilibriums.

Socio-Economic Pressures and Interest Groups:

Think of labor unions advocating for stronger worker protections or business associations lobbying for deregulation. These interest groups act as powerful agents of change, pushing for institutional reforms that align with their specific needs. The strength and organization of these groups, along with their ability to mobilize resources, significantly influence the pace and direction of institutional evolution.

Ideational Shifts and Normative Change:

Public opinion, shaped by education, media, and cultural shifts, can drive institutional change. For example, the growing acceptance of gender equality has led to reforms promoting women's political participation in many countries. Normative change, often fueled by social movements and intellectual discourse, can challenge existing institutional arrangements and pave the way for new ones.

International Influences and Diffusion:

Globalization and international organizations play a significant role in institutional change. Countries often adopt institutional models from successful peers, a process known as institutional diffusion. For instance, the spread of democratic institutions after the Cold War was facilitated by international pressure and the perceived legitimacy of democratic norms.

Institutional Design and Feedback Loops:

The very design of institutions can influence their own stability or change. Self-reinforcing mechanisms, like incumbency advantages or veto points, can make institutions resistant to reform. Conversely, institutions with built-in flexibility and mechanisms for adaptation are more likely to evolve in response to changing circumstances.

Understanding these factors allows us to move beyond simplistic narratives of institutional change as either inevitable progress or stubborn resistance. It highlights the complex interplay of historical legacies, societal forces, and international dynamics that shape the evolution of political institutions over time.

Is Hermaphrodite a Polite Term? Understanding Respectful Language for Intersex Individuals

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political institutionalism is a theoretical approach in political science that focuses on the role of institutions in shaping political behavior, outcomes, and processes. It emphasizes how formal and informal rules, norms, and structures influence governance, policy-making, and power dynamics within a political system.

Political institutionalism examines both formal institutions (e.g., constitutions, legislatures, courts) and informal institutions (e.g., norms, traditions, and cultural practices). It also explores how these institutions interact and evolve over time.

Unlike theories that prioritize individual actors, ideologies, or economic factors, political institutionalism centers on the constraints and opportunities created by institutions. It argues that institutions are not merely tools of powerful actors but have independent effects on political behavior and outcomes.

Political institutionalism provides a framework for analyzing how institutions stabilize or destabilize political systems, facilitate or hinder policy change, and mediate conflicts. It helps explain why similar policies or behaviors may produce different outcomes in varying institutional contexts.