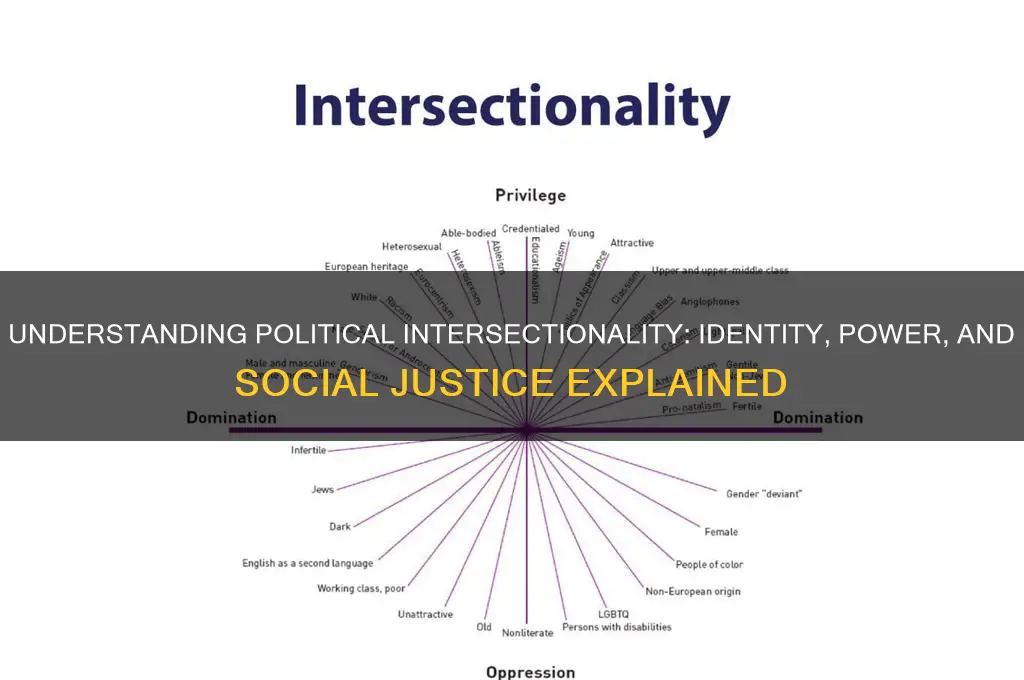

Political intersectionality refers to the examination of how various social identities, such as race, gender, class, sexuality, and disability, intersect with political systems and power structures to shape individuals' experiences and opportunities. Rooted in Kimberlé Crenshaw's framework of intersectionality, this concept highlights that these identities do not exist in isolation but interact in complex ways, often resulting in unique forms of discrimination or privilege. In politics, intersectionality critiques traditional approaches that treat issues like racism, sexism, or economic inequality as separate, instead advocating for a holistic understanding of how these systems overlap to influence policy, representation, and social justice movements. By centering marginalized voices and addressing systemic inequalities, political intersectionality seeks to create more inclusive and equitable political frameworks that account for the diverse realities of all individuals.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | The interconnected nature of social categorizations (e.g., race, class, gender) in shaping political experiences and systems. |

| Origin | Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, rooted in Black feminist thought. |

| Key Focus | How overlapping identities (e.g., race + gender + class) impact political oppression and privilege. |

| Political Application | Analyzes how policies and systems disproportionately affect marginalized groups. |

| Intersectional Movements | Examples: #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ+ rights movements. |

| Global Perspective | Considers how colonialism, globalization, and migration intersect with identity politics. |

| Critiques | Challenges single-axis frameworks (e.g., focusing solely on gender or race). |

| Policy Implications | Advocates for inclusive policies addressing multiple forms of discrimination. |

| Academic Disciplines | Widely used in political science, sociology, gender studies, and law. |

| Contemporary Relevance | Central to discussions on equity, diversity, and social justice in politics. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Origins and Definition: Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, intersectionality examines overlapping identities and their impact on oppression

- Race and Gender: Analyzes how race and gender intersect to shape political experiences and power dynamics

- Class and Identity: Explores how socioeconomic class interacts with other identities in political contexts

- Policy Implications: Discusses how intersectionality influences policy creation and implementation for marginalized groups

- Global Perspectives: Examines intersectionality’s application across cultures and its role in international politics

Origins and Definition: Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, intersectionality examines overlapping identities and their impact on oppression

Kimberlé Crenshaw, a pioneering legal scholar and critical race theorist, introduced the term "intersectionality" in the late 1980s to address the limitations of single-axis frameworks in understanding oppression. Her groundbreaking work highlighted how Black women’s experiences of discrimination could not be fully captured by examining racism or sexism in isolation. Instead, she argued, their unique struggles arise from the *interaction* of these identities, creating distinct forms of marginalization. This insight challenged traditional feminist and anti-racist movements, which often prioritized the experiences of white women or Black men, respectively, while overlooking those positioned at the crossroads of multiple systems of power.

To grasp intersectionality’s core, consider this analytical framework: it operates as a lens, not a checklist. It’s not merely about acknowledging that someone is, say, a Latina lesbian with a disability, but about understanding how these identities *intersect* to shape her access to resources, representation, and safety. For instance, a Latina immigrant may face workplace exploitation due to her race, gender, and immigration status, yet traditional labor laws might fail to address this compounded vulnerability. Intersectionality demands that policies and analyses account for these overlapping dynamics, rather than treating oppression as a sum of discrete parts.

Practically applying intersectionality requires a shift from universal solutions to context-specific strategies. For example, a political campaign advocating for gender equality must consider how class, ethnicity, and ability further stratify women’s experiences. A one-size-fits-all approach—such as equal pay legislation—might exclude low-income women of color who also face barriers to education or healthcare. By incorporating intersectional analysis, advocates can design targeted interventions, such as bilingual job training programs or childcare subsidies for single mothers, that address layered disadvantages.

Critics sometimes mischaracterize intersectionality as a tool for competition over whose oppression is "worst," but this misses its collaborative potential. Crenshaw’s framework is not about ranking suffering; it’s about revealing how power structures *differentially* impact individuals and communities. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, intersectionality illuminated why Black and Indigenous communities experienced higher mortality rates: systemic racism, inadequate healthcare access, and occupational hazards converged to create disproportionate risk. This insight doesn’t diminish other groups’ struggles—it calls for coalition-building that recognizes shared and distinct vulnerabilities.

Ultimately, intersectionality is both a diagnostic tool and a call to action. It challenges us to dismantle systems of oppression by addressing their complexity, not just their symptoms. For policymakers, activists, and educators, adopting an intersectional lens means asking: *Whose voices are missing? How do policies inadvertently exclude?* By centering these questions, we move beyond superficial diversity initiatives toward transformative justice—a goal Crenshaw’s framework has made not just possible, but imperative.

Mastering Political Economy Analysis: Strategies for Understanding Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Race and Gender: Analyzes how race and gender intersect to shape political experiences and power dynamics

Political intersectionality reveals that race and gender are not isolated identities but interlocking systems that shape political experiences and power dynamics. A Black woman, for instance, doesn’t simply face racism or sexism in politics—she encounters a unique blend of both, often amplified by their intersection. This compounding effect means her access to political representation, her treatment within institutions, and her ability to mobilize are distinctly different from those of a white woman or a Black man.

Consider voter suppression tactics in the U.S. Strict ID laws disproportionately affect Black and Latina women, who are more likely to face barriers in obtaining required documentation. This isn’t just racism or sexism; it’s the intersection of both, strategically deployed to disenfranchise a specific demographic. Analyzing such policies through an intersectional lens exposes how race and gender are weaponized together to maintain political power structures.

To address these dynamics, policymakers and activists must adopt targeted strategies. For example, voter education campaigns should be tailored to reach Black and Latina women in linguistically and culturally appropriate ways. Providing on-site ID assistance at polling places in predominantly minority neighborhoods can mitigate barriers. These solutions require recognizing the specific challenges faced by women of color, rather than treating race and gender as separate issues.

Critics might argue that intersectionality complicates political strategies, making them harder to implement. However, ignoring these intersections leads to ineffective solutions. A one-size-fits-all approach to gender equality, for instance, fails women of color who face barriers white women do not. By embracing intersectionality, political movements become more inclusive, more precise, and ultimately more powerful in dismantling systemic inequalities.

In practice, intersectional analysis demands constant vigilance and adaptation. It requires asking: How does this policy affect Black women specifically? Are Latina candidates receiving the same support as white women? By centering these questions, political actors can move beyond surface-level diversity initiatives and address the root causes of inequality. This isn’t just about fairness—it’s about creating a political landscape where power is truly shared, not hoarded by those at the top of intersecting hierarchies.

Understanding the Core: What is the Political Definition?

You may want to see also

Class and Identity: Explores how socioeconomic class interacts with other identities in political contexts

Socioeconomic class is not a standalone factor in political contexts; it intertwines with other identities like race, gender, and sexuality to shape experiences and outcomes. For instance, a working-class Black woman faces a unique set of challenges compared to a middle-class white woman, even within the same political system. This interplay of class with other identities is a cornerstone of political intersectionality, revealing how power and privilege are distributed unevenly. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for crafting policies that address systemic inequalities rather than perpetuating them.

Consider the following scenario: a policy aimed at increasing minimum wage might be hailed as a victory for low-income workers. However, if it fails to account for the disproportionate number of women and people of color in low-wage jobs, it risks overlooking the compounded impact of class, gender, and race. For example, Latina women in the U.S. are more likely to work in service industries with fewer labor protections, meaning a wage increase alone won’t address their specific vulnerabilities. An intersectional approach would pair wage reforms with measures like affordable childcare and anti-discrimination training, ensuring the policy benefits all workers equitably.

To effectively address class and identity in political contexts, follow these steps: first, disaggregate data by class, race, gender, and other identities to identify overlapping disparities. Second, involve marginalized communities in policy design to ensure their unique needs are met. Third, advocate for comprehensive solutions that tackle systemic barriers, such as education reform, healthcare access, and housing policies. Caution against one-size-fits-all approaches, as they often benefit dominant groups while leaving others behind. For example, a universal basic income program must consider how single parents, immigrants, and disabled individuals might face additional hurdles in accessing or utilizing such benefits.

A comparative analysis of class and identity across countries highlights the global relevance of this issue. In India, the caste system intersects with class, creating deep-rooted inequalities that political movements like Dalit activism seek to challenge. In Brazil, Afro-Brazilians in lower socioeconomic classes face both racial discrimination and economic exclusion, necessitating policies that address both fronts. These examples underscore the need for context-specific strategies that recognize the unique ways class interacts with other identities in different political landscapes.

Finally, the takeaway is clear: ignoring the intersection of class with other identities in political contexts perpetuates inequality. By adopting an intersectional lens, policymakers, activists, and citizens can create more inclusive and effective solutions. Practical tips include conducting intersectional audits of existing policies, prioritizing grassroots voices in decision-making, and investing in long-term initiatives that address root causes rather than symptoms. Only then can we move toward a political system that truly serves all its constituents.

Karen Polito's Election Outcome: Did She Secure the Victory?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Policy Implications: Discusses how intersectionality influences policy creation and implementation for marginalized groups

Intersectionality reveals that marginalized groups often face compounded, overlapping forms of discrimination, yet policies frequently address these issues in isolation. For instance, a policy aimed at improving women’s economic opportunities might overlook how race, disability, or immigration status further marginalize specific subgroups. This siloed approach fails to address the complex realities of those at the intersections of multiple identities, rendering such policies ineffective or exclusionary. To create meaningful change, policymakers must adopt an intersectional lens that acknowledges these interwoven systems of oppression.

Consider the implementation of healthcare policies. A one-size-fits-all approach assumes all women face the same barriers to accessing care, ignoring how factors like socioeconomic status, ethnicity, or sexual orientation exacerbate disparities. For example, Black transgender women may face discrimination from healthcare providers, lack insurance due to employment discrimination, and live in areas with limited medical resources. An intersectional policy would address these layered barriers by integrating cultural competency training for providers, expanding Medicaid coverage, and funding community health centers in underserved areas. Without such specificity, policies risk perpetuating inequities rather than dismantling them.

Instructively, crafting intersectional policies requires a multi-step process. First, disaggregate data by race, gender, class, and other identity markers to identify disparities. Second, engage directly with affected communities to understand their unique needs—tokenistic consultation is insufficient. Third, design policies with targeted interventions that address intersecting vulnerabilities. For example, a housing policy might prioritize subsidies for single mothers of color, who face both gendered poverty and racial discrimination in the housing market. Finally, establish accountability mechanisms to ensure policies are implemented as intended and adjusted based on ongoing feedback.

Persuasively, the cost of ignoring intersectionality in policy is not just moral but practical. Policies that fail to account for intersectionality often result in wasted resources and missed opportunities. For instance, a job training program that does not consider language barriers for immigrant women or childcare needs for low-income mothers will have limited impact. Conversely, intersectional policies yield higher returns on investment by addressing root causes of inequality. By centering the experiences of the most marginalized, policymakers can create solutions that benefit society as a whole, fostering greater equity and social cohesion.

Comparatively, the European Union’s approach to gender equality policies offers a cautionary tale. While the EU has advanced directives on pay equity and parental leave, these policies often neglect the experiences of migrant women, women with disabilities, and LGBTQ+ individuals. In contrast, Canada’s Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) framework explicitly integrates intersectionality into policy development, examining how factors like race, income, and disability intersect with gender. This comparative analysis underscores the importance of moving beyond surface-level inclusivity to embed intersectionality at every stage of policy creation and implementation.

Decoding Political Content: Strategies, Impact, and Audience Engagement Explained

You may want to see also

Global Perspectives: Examines intersectionality’s application across cultures and its role in international politics

Political intersectionality, when applied globally, reveals how power structures and identities interact differently across cultures, often challenging Western-centric frameworks. For instance, in many African societies, the intersection of gender and tribal affiliation shapes political participation more than class or sexuality. A woman from a minority tribe in Kenya may face barriers not only due to her gender but also her ethnic identity, which complicates her access to political representation. This example underscores the need to adapt intersectional analysis to local contexts, avoiding the imposition of universal categories that ignore cultural nuances.

To effectively apply intersectionality in international politics, follow these steps: first, identify the dominant identity markers within a specific cultural context, such as caste in India or indigeneity in Latin America. Second, analyze how these markers intersect with global systems like colonialism, capitalism, and migration. For example, indigenous women in Guatemala experience violence not only as women but as indigenous people historically marginalized by colonial legacies. Third, engage local activists and scholars to ensure the analysis respects indigenous knowledge and avoids cultural imperialism.

A cautionary note: intersectionality, when misapplied, can oversimplify complex cultural dynamics or reinforce stereotypes. For instance, reducing Middle Eastern women’s political struggles solely to religion overlooks the role of colonialism, authoritarianism, and economic policies. Similarly, assuming that LGBTQ+ rights are universally understood or prioritized can ignore how these issues are framed differently across cultures. Practitioners must balance global solidarity with cultural specificity, avoiding a one-size-fits-all approach.

Comparatively, while Western intersectionality often centers race, class, and gender, non-Western contexts may prioritize caste, religion, or tribal identity. In India, Dalit women’s political activism intersects caste and gender, challenging both patriarchal norms and upper-caste dominance. In contrast, Kurdish women in the Middle East navigate gender oppression within the context of ethnic and national struggles. These examples highlight the importance of recognizing how intersectionality manifests uniquely across cultures, enriching its application in international politics.

Ultimately, the global application of intersectionality demands humility, adaptability, and a commitment to decentering Western perspectives. By acknowledging the diversity of identity markers and power structures across cultures, intersectionality can become a more inclusive tool for analyzing and addressing global political inequalities. Practical tips include collaborating with local organizations, incorporating non-Western theoretical frameworks, and prioritizing the voices of marginalized communities in every analysis. This approach not only deepens our understanding of international politics but also fosters more equitable global solutions.

Nurses in Politics: Empowering Healthcare Voices for Policy Change

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political intersectionality is a framework that examines how multiple social identities (such as race, gender, class, sexuality, and disability) intersect and influence an individual’s or group’s experiences within political systems, policies, and power structures.

Intersectionality in politics highlights how overlapping identities shape political representation, policy outcomes, and access to resources, emphasizing the need for inclusive and equitable political practices that address systemic inequalities.

Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality in the late 1980s. Politically, it applies by critiquing how single-issue approaches to politics often fail to address the complex, overlapping forms of discrimination faced by marginalized groups.

Intersectionality is crucial in political movements because it ensures that diverse voices and experiences are included, preventing the marginalization of specific groups within broader struggles for justice and equality.

An example is the fight for reproductive justice, which considers how race, class, and gender intersect to affect access to healthcare, highlighting the need for policies that address these interconnected issues holistically.