Sparta, an ancient Greek city-state, is renowned for its unique political system, which was deeply intertwined with its militaristic culture and societal structure. Unlike other Greek poleis, Sparta was governed by a dual monarchy, with two kings sharing power, alongside a council of elders known as the Gerousia and a citizen assembly called the Apella. This system, rooted in the reforms of Lycurgus, prioritized the collective good and military strength over individual ambition, creating a highly disciplined and hierarchical society. The Spartan political framework was designed to maintain stability and ensure the dominance of the Spartan military, with citizens, known as Spartiates, dedicating their lives to warfare and the state. This distinct political organization set Sparta apart from its contemporaries, making it a fascinating subject for understanding the intersection of politics, culture, and power in the ancient world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Government Structure | Dyarchy (rule by two kings) with a strong oligarchical element |

| Kings | Two hereditary kings, serving as military leaders and religious figures, but with limited political power |

| Gerousia (Council of Elders) | 28 elected members over 60 years old, plus the two kings; held significant legislative and judicial power |

| Apella (Assembly) | All Spartan citizens could participate, but primarily ratified decisions made by the Gerousia |

| Ephors | Five annually elected officials with broad powers, including overseeing the kings and controlling foreign policy |

| Citizenship | Restricted to full Spartan citizens (Spartiates), who were a minority of the population |

| Helots | Enslaved state-owned population, providing agricultural labor and forming the majority of the population |

| Military Focus | Society centered around military training and service; all male citizens trained as soldiers from a young age |

| Education System | Agoge: rigorous state-sponsored education system for boys, emphasizing discipline, endurance, and loyalty to Sparta |

| Women's Role | Relatively more freedom compared to other Greek city-states; managed households and property while men were in military service |

| Economy | Agrarian-based, reliant on helot labor; discouraged trade and wealth accumulation among citizens |

| Foreign Policy | Expansionist and militaristic, often in conflict with neighboring states, particularly Athens |

| Social Structure | Rigid hierarchy: Spartiates (citizens) > Perioikoi (free non-citizens) > Helots (enslaved population) |

| Legal System | Laws attributed to Lycurgus, emphasizing simplicity and austerity; focus on maintaining social order |

| Religion | Polytheistic, with a strong emphasis on state-sponsored cults and rituals to ensure divine favor |

| Cultural Values | Austerity, discipline, loyalty, and military prowess were highly valued; luxury and individualism discouraged |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Military-Centric Society: Sparta's political system revolved around maintaining a powerful, disciplined military force

- Dual Kingship: Two kings shared power, balancing religious and military leadership roles

- Gerousia Council: Elders advised kings, ensuring stability and traditional governance in Spartan politics

- Helot Dependency: Political power relied on exploiting helot labor for economic and military focus

- Agoge System: State-controlled education trained citizens for loyalty, obedience, and military service

Military-Centric Society: Sparta's political system revolved around maintaining a powerful, disciplined military force

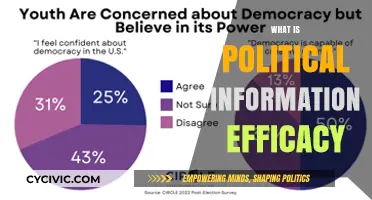

Sparta's political system was uniquely structured around the primacy of its military, a fact that shaped every aspect of Spartan life. From birth, Spartan citizens were evaluated for physical strength, with weak or deformed infants often left to die in a practice known as exposure. Those who survived were groomed from the age of seven to become hoplites, the heavily armored infantry soldiers that formed the backbone of Sparta's military might. This ruthless selection process ensured that only the fittest and most capable individuals contributed to the state's defense, a policy that prioritized military readiness above all else.

The Spartan government, known as the *diarchy*, featured two kings who served as both political leaders and military commanders. This dual role underscores the inseparable link between political power and military prowess in Spartan society. The kings were supported by the *Gerousia*, a council of 28 elders over the age of 60, who were chosen for their wisdom and experience, often gained through a lifetime of military service. This system ensured that decision-making was informed by a deep understanding of warfare and strategy, further cementing the military's central role in Spartan politics.

To maintain discipline and combat readiness, Spartan citizens lived in a highly regulated environment. The *agoge*, a rigorous state-sponsored education and training system, indoctrinated young Spartans in the values of obedience, endurance, and loyalty to the state. This training was not merely physical but also psychological, designed to instill a collective mindset that prioritized the welfare of Sparta above individual desires. The result was a society where military service was not just a duty but the defining purpose of every citizen's life.

A comparative analysis reveals how Sparta's military-centric system contrasted with other Greek city-states. While Athens, for example, thrived as a center of culture, philosophy, and democracy, Sparta's focus on military discipline limited its contributions to art, literature, and civic innovation. However, this singular focus granted Sparta unparalleled military dominance, as evidenced by its victory in the Peloponnesian War. The takeaway is clear: Sparta's political system was a masterclass in specialization, sacrificing diversity for unparalleled strength in a single, critical area.

For modern readers seeking to draw lessons from Sparta, the key lies in understanding the trade-offs of such a system. While a military-centric approach can ensure security and stability, it often comes at the expense of individual freedoms and cultural development. Practical tips for implementing Spartan principles in contemporary contexts might include fostering discipline and teamwork in organizational structures, though caution must be exercised to avoid the extreme measures that defined Spartan society. Ultimately, Sparta's political system serves as a cautionary tale about the costs and benefits of prioritizing military power above all else.

Rescheduling Interviews Gracefully: A Guide to Professional Communication

You may want to see also

Dual Kingship: Two kings shared power, balancing religious and military leadership roles

Sparta's dual kingship system was a cornerstone of its political structure, a unique arrangement that defied conventional notions of monarchy. Imagine a state led not by one, but two kings, each holding distinct yet complementary roles. This wasn't a power struggle waiting to happen; it was a deliberate design aimed at stability and balance. One king, descended from the Agiad dynasty, focused on religious duties, acting as the intermediary between the gods and the Spartan people. The other, from the Eurypontid line, took charge of military affairs, leading the formidable Spartan army into battle. This division wasn't merely symbolic; it was a practical solution to the complexities of governing a warrior society.

This dual kingship wasn't without its intricacies. While both kings held equal authority in theory, the military king often wielded greater influence due to Sparta's constant state of readiness for war. However, the religious king's role was equally vital, ensuring the favor of the gods through rituals and sacrifices, a crucial aspect in a society deeply rooted in superstition. This dynamic duo wasn't just a leadership team; they were a symbol of Sparta's dual nature, a society that valued both spiritual devotion and martial prowess.

The system's effectiveness lay in its ability to prevent the concentration of power. By dividing responsibilities, Sparta minimized the risk of tyranny and fostered a sense of shared governance. This wasn't democracy as we understand it today, but it was a step towards distributing authority, a concept rare in the ancient world. The dual kingship served as a check and balance, ensuring that no single individual could dominate Spartan politics.

However, this system wasn't without its challenges. The potential for rivalry between the kings was ever-present, and history records instances of tension and even conflict. Yet, Sparta's ephors, a council of five elected officials, acted as a further check, holding the kings accountable and mediating disputes. This intricate web of power distribution showcases Sparta's political ingenuity, a system designed to maintain stability in a society constantly on the brink of war.

In essence, Sparta's dual kingship was a masterclass in political engineering. It wasn't just about having two kings; it was about creating a system where religious and military leadership were intertwined, where power was shared and balanced, and where the state's unique needs were met through a carefully crafted division of labor. This ancient model, though not without flaws, offers a fascinating glimpse into the complexities of governance and the innovative solutions that can arise from a society's specific circumstances.

Are You a Political Extremist? Uncovering the Signs and Solutions

You may want to see also

Gerousia Council: Elders advised kings, ensuring stability and traditional governance in Spartan politics

Spartan politics were uniquely structured to prioritize stability and adherence to tradition, a framework embodied by the Gerousia Council. This body of 28 elders, along with the two kings, formed the backbone of Spartan governance. Elected for life by the Spartan assembly, the Gerousia’s members were required to be over 60 years old, a stipulation that ensured their decisions were informed by decades of experience and a deep understanding of Spartan customs. This age requirement was no accident; it was a deliberate mechanism to safeguard against impulsive or radical changes, anchoring the state in its time-tested principles.

The Gerousia’s primary role was to advise the kings, who, despite their royal status, were not absolute rulers. This advisory function was critical in maintaining a balance of power. The council reviewed and debated proposals before they were presented to the assembly, effectively acting as a filter for legislation. For instance, if a king proposed a military campaign, the Gerousia would scrutinize its feasibility, alignment with Spartan interests, and potential consequences. This process not only ensured that decisions were well-considered but also reinforced the collective nature of Spartan leadership, preventing any single individual from dominating the political landscape.

One of the most striking aspects of the Gerousia was its role in preserving Spartan traditions. The council was tasked with upholding the *Great Rhetra*, a constitution attributed to the legendary lawgiver Lycurgus. This document enshrined the principles of Spartan society, including the importance of military discipline, communal living, and the subordination of individual desires to the state’s needs. By interpreting and enforcing these laws, the Gerousia acted as the guardian of Spartan identity, ensuring that even in times of external pressure or internal strife, the core values of the state remained intact.

To understand the Gerousia’s impact, consider its handling of crises. During the Peloponnesian War, for example, the council’s steady hand guided Sparta through complex diplomatic and military challenges. While younger voices in the assembly might have pushed for aggressive expansion, the Gerousia often advocated for caution, prioritizing long-term stability over short-term gains. This approach was not without criticism, but it underscores the council’s commitment to its mandate: to preserve Sparta’s traditional governance, even when it meant resisting popular or expedient solutions.

In practical terms, the Gerousia’s model offers a lesson in the value of intergenerational leadership. By entrusting elders with significant political authority, Sparta created a system where experience and wisdom were institutionalized. For modern societies grappling with rapid change and polarization, this structure suggests a potential remedy: incorporating mechanisms that amplify the voices of older, more experienced individuals in decision-making processes. While the specifics of Spartan governance may not translate directly to contemporary contexts, the underlying principle—that stability and tradition require deliberate cultivation—remains profoundly relevant.

Politics and the Judiciary: Examining the Impact on Judicial Independence

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Helot Dependency: Political power relied on exploiting helot labor for economic and military focus

Sparta's political system was uniquely structured around the exploitation of helot labor, a dependency that underpinned its economic stability and military prowess. Helots, an enslaved population primarily from Messenia and Laconia, formed the backbone of Spartan agriculture, allowing full citizens (Spartiates) to focus entirely on military training and governance. This division of labor was not merely an economic arrangement but a political strategy, ensuring that Spartiates remained unencumbered by mundane tasks and could dedicate themselves to maintaining their oligarchical rule. Without helot labor, Sparta’s military-centric society would have been unsustainable, as citizens would have been forced to divert their efforts to farming rather than warfare.

The relationship between Spartiates and helots was inherently unstable, yet it was managed through a combination of coercion and calculated control. The helot population vastly outnumbered the Spartiates, creating a constant threat of rebellion. To mitigate this, Sparta implemented harsh measures, such as the *Krypteia*, a secret police-like force of young Spartiates tasked with terrorizing helots and suppressing dissent. This system of fear and violence was not just a security measure but a political tool, reinforcing Spartan dominance by keeping the helots subjugated. The reliance on such extreme methods highlights the fragility of Sparta’s political power, which was built on the precarious foundation of forced labor.

Economically, helot labor was the lifeblood of Sparta’s agrarian economy. Helots cultivated the land, producing surplus goods that sustained the Spartan state and funded its military campaigns. This economic dependency allowed Spartiates to maintain their austere, warrior-focused lifestyle without engaging in trade or commerce, which they viewed as beneath them. However, this reliance also created a paradox: while helots were essential to Sparta’s survival, their exploitation was a constant source of tension. The political elite had to balance the need for helot labor with the risk of rebellion, a delicate equilibrium that shaped every aspect of Spartan policy.

Comparatively, other Greek city-states relied on citizen labor, foreign trade, or mercenary forces to sustain their economies and militaries. Athens, for instance, thrived on commerce and democracy, while Sparta’s isolationist policies and militarism were made possible only through the systematic exploitation of helots. This contrast underscores the uniqueness of Sparta’s political system, which was fundamentally parasitic. The helots were not just laborers but a political instrument, enabling Sparta to project military power while maintaining a rigid social hierarchy. Without them, Sparta’s political identity as a dominant military state would have been impossible.

In practical terms, understanding Sparta’s helot dependency offers insights into the fragility of systems built on exploitation. Modern societies can draw parallels to how economic and political power often rests on marginalized labor forces. Sparta’s example serves as a cautionary tale: while such systems may achieve short-term stability and strength, they are inherently unstable and require increasingly brutal measures to maintain control. For historians and policymakers alike, studying this dynamic provides a lens through which to analyze the sustainability of power structures and the ethical implications of labor exploitation.

Unveiling the Dark Side: Political Bosses and Their Corrupt Practices

You may want to see also

Agoge System: State-controlled education trained citizens for loyalty, obedience, and military service

Sparta's Agoge system was a rigorous, state-controlled education program designed to mold citizens into loyal, obedient, and militarily proficient warriors. From the age of 7, Spartan boys were removed from their families and placed into state-run barracks, where they underwent a harsh training regimen that prioritized physical endurance, discipline, and collective identity over individualism. This system was not merely about producing soldiers; it was a political tool to ensure the stability and dominance of the Spartan state. By instilling unwavering loyalty to the state and a deep-seated sense of duty, the Agoge system effectively eliminated dissent and fostered a society singularly focused on military excellence and the preservation of Sparta’s unique political structure.

The curriculum of the Agoge was meticulously structured to achieve its political objectives. Boys were subjected to extreme physical challenges, such as endurance marches, minimal food rations, and exposure to the elements, all designed to harden them both physically and mentally. Alongside physical training, they were taught the values of obedience, self-sacrifice, and the supremacy of the state. Education in academics was minimal, as the focus was on practical skills necessary for warfare and survival. This deliberate limitation of knowledge ensured that citizens remained dependent on the state’s guidance and less likely to question its authority. The Agoge system thus served as both a training ground and a mechanism for political control.

A key aspect of the Agoge system was its emphasis on collective identity over individual achievement. Boys were organized into groups called *agelai* (herds), where competition and camaraderie were fostered within the group, but loyalty to the group itself was paramount. This structure discouraged individualism and encouraged a sense of belonging to the larger Spartan community. Punishments for failure or disobedience were often public and severe, reinforcing the idea that personal shortcomings were a betrayal of the state. By the time boys completed the Agoge at age 20, they were not just soldiers but indoctrinated citizens whose primary identity was as a protector of Sparta’s political order.

To implement a modern analogy, the Agoge system can be compared to highly structured military academies, though with far more extreme measures and political intent. For those interested in understanding its principles, consider the following practical takeaways: focus on consistent, rigorous training; prioritize group cohesion over individual accolades; and ensure that every aspect of the program reinforces the core values of loyalty and duty. However, caution must be exercised in applying such a system in contemporary contexts, as its success in Sparta was built on a society that valued militarism above all else, a framework that may not align with modern ethical or political norms.

In conclusion, the Agoge system was a masterclass in political engineering, using education as a tool to shape citizens into instruments of state power. Its success lay in its ability to merge physical training, ideological indoctrination, and social conditioning into a seamless program that produced not just warriors, but unwavering defenders of Sparta’s political ideology. While its methods may seem extreme by today’s standards, the Agoge system remains a fascinating study in how education can be wielded as a political instrument to achieve specific societal goals.

Understanding Political Legitimacy: Foundations, Challenges, and Modern Implications

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Ancient Sparta was an oligarchy, ruled by two kings who served as military leaders and high priests, alongside a council of elders (Gerousia) and an assembly of citizens (Apella). The Ephors, a group of five elected officials, held significant power in overseeing the kings and maintaining order.

Sparta’s political system was unique in its focus on militarism and the suppression of individualism. Unlike Athens, which embraced democracy, Sparta prioritized the collective good of the state and the maintenance of its military dominance, with citizens trained from a young age to be warriors.

The helots, a subjugated population of state-owned serfs, were essential to Sparta’s political and economic stability. They performed agricultural labor, allowing Spartan citizens to focus on military training. However, their exploitation and potential for rebellion were constant concerns, shaping Spartan policies and societal structure.