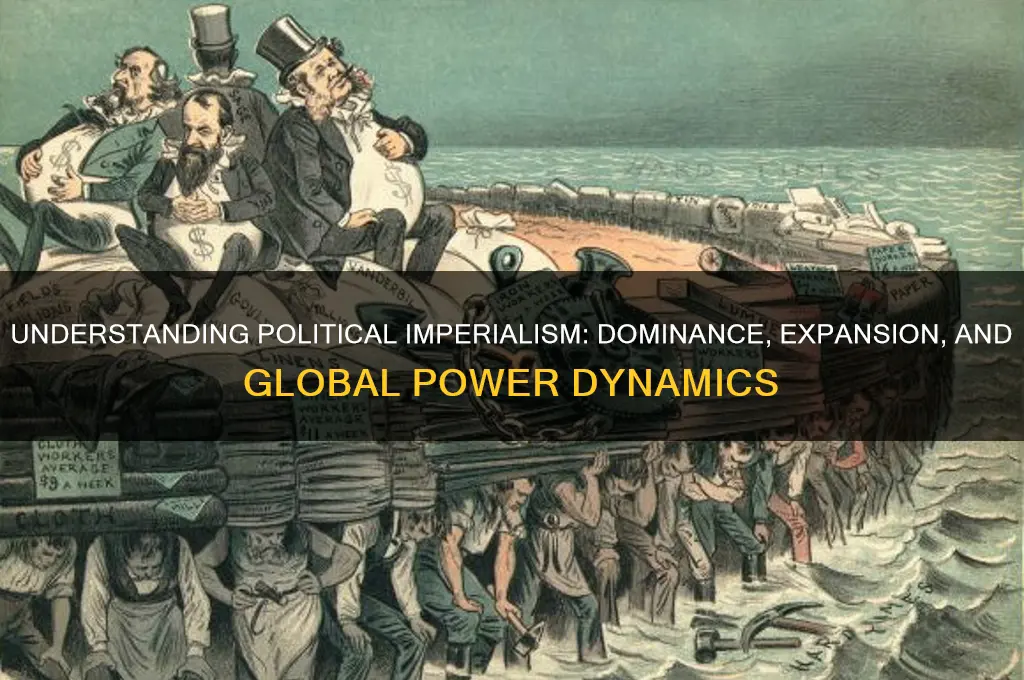

Political imperialism refers to the practice of a powerful nation extending its authority, control, or influence over other territories, often through diplomatic, economic, or military means. It involves the domination of one state over another, typically resulting in the exploitation of resources, the imposition of cultural or political systems, and the suppression of local autonomy. Historically, imperialist powers have justified their actions through ideologies such as the civilizing mission or the belief in racial or cultural superiority, while the consequences for colonized regions often include economic dependency, cultural erosion, and political subjugation. Understanding political imperialism is crucial for analyzing global power dynamics, historical injustices, and the ongoing impacts of colonialism on contemporary societies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Domination and Control | One country exerts political authority over another, often through direct or indirect means. |

| Colonial Expansion | Acquisition of territories through conquest, settlement, or annexation. |

| Exploitation of Resources | Extraction of economic resources (e.g., raw materials, labor) from colonized regions. |

| Cultural Suppression | Imposition of the colonizer's culture, language, and values on the colonized population. |

| Military Presence | Deployment of military forces to maintain control and suppress resistance. |

| Economic Dependency | Creation of economic systems that benefit the imperial power at the expense of the colony. |

| Political Subordination | Denial of self-governance and political rights to the colonized population. |

| Ideological Justification | Use of ideologies (e.g., "civilizing mission," racial superiority) to legitimize imperialism. |

| Administrative Integration | Incorporation of colonies into the imperial power's administrative and legal systems. |

| Resistance and Nationalism | Emergence of anti-colonial movements and nationalist sentiments in response to imperialism. |

| Global Influence | Projection of power and influence across multiple regions to shape global politics. |

| Legacy of Inequality | Long-term socioeconomic disparities and political instability in formerly colonized regions. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Economic Exploitation: Extracting resources, labor, and wealth from colonized territories to enrich the imperial power

- Cultural Domination: Imposing language, religion, values, and customs of the imperial power on colonized societies

- Political Control: Establishing direct or indirect rule over territories to maintain dominance and suppress resistance

- Military Expansion: Using force to conquer and occupy territories, ensuring compliance through military presence

- Ideological Justification: Promoting ideas like civilizing missions to legitimize imperial actions and oppression

Economic Exploitation: Extracting resources, labor, and wealth from colonized territories to enrich the imperial power

Economic exploitation lies at the heart of political imperialism, serving as its lifeblood. It’s a systematic process where imperial powers drain colonized territories of their resources, labor, and wealth, funneling these assets back to the metropole. This isn’t mere trade or investment; it’s a one-sided extraction engineered to maximize profit for the colonizer while minimizing benefit—or even inflicting harm—on the colonized. Consider the Belgian Congo under King Leopold II, where rubber and ivory were extracted through forced labor, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 10 million Congolese. This wasn’t an anomaly but a blueprint: from British India’s textile industry to Spanish silver mines in Potosí, economic exploitation was the engine of imperial dominance.

To understand how this works, imagine a three-step process. First, resource extraction: imperial powers identify and seize control of valuable commodities—minerals, agricultural products, or raw materials. For instance, the British East India Company monopolized India’s opium trade, using it to balance trade deficits with China. Second, labor exploitation: local populations are coerced into working under brutal conditions, often through taxation, debt bondage, or outright violence. In Kenya, the British forced locals into labor camps to build the Uganda Railway, with thousands dying from disease and overwork. Third, wealth transfer: profits from these activities are repatriated to the imperial power, leaving little to no investment in local infrastructure or development. This cycle ensures the colonized remain dependent, their economies distorted to serve foreign interests.

The persuasive argument here is clear: economic exploitation isn’t a byproduct of imperialism—it’s its purpose. Imperial powers justify their dominance by claiming to bring "civilization" or "progress," but the numbers tell a different story. During British rule, India’s share of the global economy plummeted from 23% in 1700 to 4% in 1950, while Britain’s wealth soared. This isn’t coincidence; it’s design. Modern parallels persist in neocolonial practices, where multinational corporations extract resources from former colonies under exploitative trade agreements. The takeaway? Economic exploitation isn’t a relic of the past—it’s a living system that continues to shape global inequality.

Comparatively, while military conquest and cultural assimilation are visible facets of imperialism, economic exploitation is its invisible hand. It operates through policies, trade agreements, and financial systems that appear neutral but are rigged in favor of the powerful. For instance, the World Bank and IMF often impose structural adjustment programs on developing nations, requiring them to open their markets to foreign corporations while cutting social spending. This modern form of exploitation mirrors colonial-era practices, ensuring wealth flows upward—from the global south to the global north. The difference? Today, it’s cloaked in the language of "development" and "free trade."

Descriptively, the human cost of economic exploitation is staggering. In the Niger Delta, Shell’s oil extraction has polluted waterways, destroyed livelihoods, and fueled conflict, while the company reaps billions in profits. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, cobalt mining for tech companies relies on child labor, with workers earning as little as $2 a day. These aren’t isolated incidents but systemic outcomes of a global economy built on exploitation. The irony? The very devices we use to read about these injustices are often made possible by this exploitation. Economic imperialism isn’t just a historical footnote—it’s embedded in our daily lives, demanding we confront its legacy and ongoing reality.

Understanding the GOP: Unraveling the Republican Party's Political Stance and Impact

You may want to see also

Cultural Domination: Imposing language, religion, values, and customs of the imperial power on colonized societies

Cultural domination, a cornerstone of political imperialism, operates through the systematic imposition of the imperial power's language, religion, values, and customs on colonized societies. This process is not merely about replacing one set of practices with another; it is a deliberate strategy to erase indigenous identities, disrupt local systems of knowledge, and establish long-term control. For instance, during the British Raj in India, English was institutionalized as the language of administration, education, and prestige, marginalizing native languages like Hindi and Bengali. This linguistic shift was not accidental but a calculated move to create a class of intermediaries who would perpetuate colonial rule even after political independence.

The imposition of religion often serves as a dual-edged sword in cultural domination. Imperial powers frequently use religious conversion as a tool to dismantle existing belief systems and foster dependency on the colonizer's spiritual authority. The Spanish colonization of the Americas exemplifies this, where Catholicism was forcefully introduced alongside the destruction of indigenous temples and sacred texts. The result was a hybridized religious landscape, but one that ultimately centered European spiritual dominance. This religious imposition was often accompanied by laws and social structures that privileged converts, further entrenching the imperial power's cultural hegemony.

Values and customs, too, become weapons in the arsenal of cultural domination. Imperial powers often portray their societal norms as universally superior, framing local traditions as backward or primitive. In French West Africa, for example, the French promoted their notions of modernity, including Western dress, etiquette, and family structures, as the ideal. Schools and media were used to disseminate these values, creating a generational divide where younger, educated Africans often internalized French customs at the expense of their own heritage. This cultural displacement not only weakened communal bonds but also fostered a sense of inferiority toward indigenous practices.

To resist cultural domination, colonized societies must engage in active reclamation and preservation of their languages, religions, and customs. Practical steps include integrating indigenous languages into formal education systems, as seen in post-colonial nations like Rwanda and South Africa. Additionally, intergenerational knowledge transfer through oral traditions, art, and community events can counteract the erosion of local values. Policymakers and educators should also prioritize decolonizing curricula by incorporating diverse perspectives and histories, ensuring that imperial narratives are not the sole framework for understanding the past.

Ultimately, cultural domination is a subtle yet enduring legacy of political imperialism, one that requires vigilant and proactive efforts to dismantle. By understanding its mechanisms and implementing targeted strategies, societies can reclaim their cultural autonomy and foster a more equitable global dialogue. The challenge lies not just in preserving traditions but in reimagining them as dynamic, living practices that resist homogenization while embracing diversity.

Navigating Family Politics: Strategies for Peace and Harmony at Home

You may want to see also

Political Control: Establishing direct or indirect rule over territories to maintain dominance and suppress resistance

Political control is the backbone of imperialism, a system where dominant powers extend their authority over other territories, often through a mix of coercion and manipulation. Establishing direct or indirect rule allows imperial powers to extract resources, enforce cultural norms, and suppress dissent, ensuring their dominance persists. Direct rule involves administering a territory through the imperial power’s own government structures, while indirect rule relies on local elites who act as proxies, maintaining control with less overt intervention. Both methods aim to consolidate power and eliminate resistance, often at the expense of the colonized population’s autonomy and rights.

Consider the British Raj in India, a classic example of direct rule. The British Crown appointed officials to govern Indian provinces, imposed English law, and restructured the economy to serve British interests. Railways, for instance, were built not for Indian development but to transport raw materials to ports for export. Resistance movements, such as the Indian Rebellion of 1857, were brutally suppressed, with entire villages razed and leaders executed. This direct control ensured Britain’s economic and political dominance for nearly a century, while India’s resources were drained and its people marginalized.

Indirect rule, on the other hand, is exemplified by British control in Nigeria. Here, local leaders like the Emirs and Obas were retained but forced to govern according to British directives. The colonial administration manipulated traditional hierarchies, favoring certain groups over others to create divisions and weaken collective resistance. Taxes were imposed, and cash crops like cocoa and groundnuts were prioritized, disrupting local economies. This system allowed Britain to maintain control with minimal military presence, as local elites became enforcers of imperial policies. The takeaway? Indirect rule is subtler but equally effective in suppressing resistance and exploiting territories.

To establish political control, imperial powers often employ a three-step strategy: co-opt, coerce, and cultivate dependency. First, they co-opt local elites by offering privileges or protection, ensuring these leaders become stakeholders in the imperial system. Second, they coerce through military force or economic sanctions, punishing dissent and rebellion. Finally, they cultivate dependency by restructuring economies to rely on the imperial power, making resistance impractical or impossible. For instance, French control in Algeria involved co-opting tribal leaders, using military force to crush uprisings, and transforming the economy to depend on French markets for wine and grain exports.

Practical tips for understanding political control in imperialism include studying the administrative structures imposed by colonial powers, analyzing economic policies that exploit resources, and examining the suppression of local cultures and languages. Look for patterns: how were local institutions dismantled or repurposed? How were resistance movements framed as threats to "order"? By dissecting these mechanisms, one can see how political control is not just about ruling territories but about reshaping societies to serve the interests of the dominant power. The ultimate goal is to make resistance futile, ensuring the imperial system endures.

Do Artifacts Have Politics? Exploring the Winner's Perspective

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Military Expansion: Using force to conquer and occupy territories, ensuring compliance through military presence

Military expansion, a cornerstone of political imperialism, involves the use of force to conquer and occupy territories, with compliance ensured through a sustained military presence. Historically, this strategy has been employed by empires seeking to extend their influence, exploit resources, and assert dominance over weaker regions. The Roman Empire, for instance, systematically expanded its borders through military campaigns, establishing garrisons in conquered lands to maintain control and integrate these territories into its administrative system. This approach not only secured economic benefits but also spread Roman culture and law, creating a lasting legacy.

To execute military expansion effectively, several steps are critical. First, identify strategic territories rich in resources or holding geopolitical significance. Second, deploy military forces to overwhelm local resistance, often leveraging superior technology or numbers. Third, establish a permanent military presence to deter rebellion and enforce order. Finally, implement policies that integrate the occupied territory into the imperial system, such as infrastructure development or cultural assimilation. However, caution must be exercised: prolonged occupations can lead to insurgencies, as seen in the British Empire’s struggles in Afghanistan or the United States’ challenges in Iraq. Balancing force with diplomacy and development is essential to avoid protracted conflicts.

A comparative analysis reveals that military expansion’s success hinges on adaptability. The Mongol Empire, for example, relied on swift cavalry invasions and local alliances to control vast territories, while the British Empire used naval supremacy and technological advantages to dominate colonial possessions. In contrast, the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan demonstrated the limitations of brute force without addressing local grievances. Modern imperialist strategies often involve proxy wars or economic coercion, but the core principle remains: military power is a tool to achieve political and economic objectives.

Persuasively, it’s argued that military expansion, while effective in the short term, carries long-term risks. The financial burden of maintaining military occupations can strain imperial economies, as evidenced by the decline of the Spanish Empire after overextending itself in the Americas. Additionally, the moral and ethical implications of subjugating populations through force have increasingly come under scrutiny in the modern era. Advocates of soft power—cultural, economic, and diplomatic influence—suggest it as a more sustainable alternative. However, for states prioritizing immediate gains, military expansion remains a tempting strategy, despite its inherent challenges.

Descriptively, the human cost of military expansion is profound. Occupied populations often face displacement, exploitation, and cultural erasure. In the Belgian Congo, King Leopold II’s private army enforced rubber production quotas through brutal violence, leading to the deaths of millions. Similarly, the Japanese Empire’s occupation of Southeast Asia during World War II was marked by forced labor and atrocities. These examples underscore the darker side of imperialism, where military force is wielded not just to conquer land, but to control and oppress people. Understanding this history is crucial for recognizing the enduring impact of such policies on global societies.

How Political Machines Effectively Shaped Urban Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Ideological Justification: Promoting ideas like civilizing missions to legitimize imperial actions and oppression

Imperial powers have long cloaked their expansionist ambitions in the rhetoric of benevolence, framing conquest as a moral duty rather than a pursuit of power. The "civilizing mission" stands as one of the most enduring and insidious justifications for imperialism, a narrative that casts the colonizer as a selfless educator and the colonized as a passive recipient of progress. This ideological construct served as a powerful tool to legitimize exploitation, oppression, and cultural erasure, all under the guise of enlightenment.

By portraying indigenous societies as "backward" or "savage," imperial powers created a narrative of necessity, arguing that intervention was not only justified but morally imperative. This discourse was not merely a post-facto rationalization; it was actively cultivated through education, media, and religious institutions, shaping public opinion and silencing dissent. The "civilizing mission" was not just a slogan but a comprehensive worldview, one that continues to influence global power dynamics to this day.

Consider the British Empire's approach to India. British officials and intellectuals often depicted India as a land mired in superstition, caste rigidity, and economic stagnation, conveniently overlooking the thriving trade networks and sophisticated governance systems that existed prior to colonization. Through the establishment of schools, missionary activities, and legal reforms, the British presented themselves as agents of modernization, even as they dismantled local industries, exploited resources, and imposed a foreign system of governance. The introduction of the English language and Western education was framed as a gift, a pathway to progress, rather than a tool of cultural domination. This narrative not only justified British rule but also created a class of Western-educated elites who often internalized the colonizer's worldview, further entrenching imperial control.

The "civilizing mission" was not unique to the British; it was a recurring theme across imperial powers, from the French in Africa to the Americans in the Philippines. Each power adapted the narrative to suit its specific context, but the underlying logic remained the same: the colonized were incapable of self-governance and required external guidance. This ideology was so pervasive that it often influenced the colonized themselves, leading to internalized inferiority complexes and the rejection of indigenous traditions. The long-term consequences of this ideological justification are still felt today, from the persistence of neocolonial structures to the ongoing struggles for cultural and political autonomy.

To dismantle the legacy of the "civilizing mission," it is essential to critically examine the narratives that justify power imbalances. This involves recognizing the agency and contributions of indigenous societies, challenging Eurocentric histories, and promoting education that highlights the complexities of colonial encounters. For educators, this means incorporating diverse perspectives into curricula and encouraging students to question dominant narratives. For policymakers, it entails addressing systemic inequalities and supporting initiatives that empower formerly colonized communities. By deconstructing the ideological justifications of imperialism, we can work toward a more equitable and just global order, one that acknowledges the inherent dignity and worth of all peoples.

Are Political Robocalls Illegal? Understanding the Legal Boundaries

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political imperialism refers to the practice of a powerful nation extending its authority, control, or influence over other territories, often through diplomatic, military, or economic means, without formal colonization.

Political imperialism focuses on gaining political control or dominance over another region, while economic imperialism emphasizes exploiting a territory's resources, markets, or labor for economic gain, often without direct political rule.

Examples include the British Empire's control over India, the French influence in Indochina (modern-day Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos), and the Soviet Union's dominance over Eastern Bloc countries during the Cold War.

Political imperialism often leads to the suppression of local cultures, political systems, and autonomy, as well as economic exploitation, social inequality, and long-term instability in the colonized regions.