A political framework refers to the structured system of principles, institutions, and processes that govern how power is distributed, exercised, and regulated within a society. It encompasses the rules, norms, and mechanisms through which decisions are made, conflicts are resolved, and public policies are formulated and implemented. Political frameworks can vary widely across different countries and cultures, ranging from democratic systems that emphasize citizen participation and representation to authoritarian regimes that centralize power in the hands of a few. Understanding a political framework is essential for analyzing how governments function, how rights and responsibilities are defined, and how societal values and interests are reflected in the political process. It serves as the foundation for the organization of political life and shapes the interactions between the state, its citizens, and other actors in the political arena.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A structured system of principles, rules, and institutions that govern political processes and decision-making. |

| Purpose | To provide a foundation for organizing and managing political power, ensuring stability, and resolving conflicts. |

| Components | Constitution, laws, political parties, electoral systems, and governance structures. |

| Types | Democratic, authoritarian, federal, unitary, parliamentary, presidential, etc. |

| Key Principles | Rule of law, separation of powers, representation, accountability, and transparency. |

| Actors | Government, political parties, interest groups, citizens, and international organizations. |

| Function | Facilitates policy-making, resource allocation, and conflict resolution within a society. |

| Flexibility | Can be rigid (e.g., codified constitutions) or flexible (e.g., uncodified conventions). |

| Scope | Operates at local, national, and international levels. |

| Evolution | Adapts over time due to societal changes, technological advancements, and global influences. |

| Influence | Shapes political culture, citizen participation, and the distribution of power. |

| Challenges | Corruption, inequality, polarization, and external interference. |

| Measurement | Assessed through indicators like democracy indices, governance scores, and electoral integrity. |

| Examples | U.S. presidential system, UK parliamentary system, EU supranational framework. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Political Ideologies: Liberalism, conservatism, socialism, and other core beliefs shaping governance and policy-making

- Government Structures: Presidential, parliamentary, federal, and unitary systems defining state organization

- Constitutional Principles: Rule of law, separation of powers, and fundamental rights in governance

- Electoral Systems: Voting mechanisms, representation models, and their impact on political outcomes

- Policy Formulation: Processes, stakeholders, and frameworks for creating and implementing public policies

Political Ideologies: Liberalism, conservatism, socialism, and other core beliefs shaping governance and policy-making

Political ideologies serve as the bedrock of governance, shaping how societies organize power, allocate resources, and define individual rights. Among the most influential are liberalism, conservatism, and socialism, each offering distinct prescriptions for policy-making. Liberalism, rooted in the Enlightenment, champions individual liberty, free markets, and limited government intervention. It prioritizes personal freedoms, such as speech and religion, and advocates for democratic institutions to safeguard these rights. In practice, liberal policies often include progressive taxation, social safety nets, and protections for marginalized groups, as seen in countries like Sweden and Canada.

Conservatism, in contrast, emphasizes tradition, stability, and hierarchical order. It views societal structures as time-tested and warns against rapid change, often favoring established institutions like religion and the family. Conservative policies typically promote free enterprise, lower taxes, and strong national defense, as exemplified by the United States under Republican administrations. While conservatism can appear rigid, it adapts to modern challenges by balancing tradition with pragmatic reforms, such as environmental conservatism, which seeks to protect natural resources without abandoning economic growth.

Socialism challenges the capitalist framework by prioritizing collective welfare over individual gain. It advocates for public ownership of key industries, equitable wealth distribution, and robust social services. Socialist policies, as implemented in countries like Norway, often include universal healthcare, free education, and worker cooperatives. Critics argue that socialism stifles innovation and economic efficiency, but proponents highlight its success in reducing inequality and ensuring basic human needs are met. The rise of democratic socialism, as seen in the policies of figures like Bernie Sanders, reflects a modern adaptation that combines socialist principles with democratic governance.

Beyond these three, other ideologies like anarchism, fascism, and environmentalism further diversify the political landscape. Anarchism rejects all forms of coercive authority, advocating for voluntary associations and decentralized decision-making. Fascism, though largely discredited after World War II, emphasizes nationalism, authoritarianism, and the suppression of dissent. Environmentalism, a newer ideology, transcends traditional left-right divides, urging governments to prioritize ecological sustainability in policy-making. For instance, the Green New Deal in the U.S. combines environmental goals with social and economic justice.

Understanding these ideologies is crucial for navigating the complexities of modern governance. While no single framework offers a perfect solution, each provides valuable insights into addressing societal challenges. Policymakers must balance competing priorities, such as individual freedom versus collective welfare, tradition versus progress, and economic growth versus environmental sustainability. By studying these ideologies, citizens can engage more critically with political debates and advocate for policies that align with their values. Ultimately, the interplay of these core beliefs shapes not only governments but also the societies they serve.

Understanding Political Action Committees: Functions, Influence, and Operations Explained

You may want to see also

Government Structures: Presidential, parliamentary, federal, and unitary systems defining state organization

The way a government is structured fundamentally shapes how power is distributed, decisions are made, and citizens are represented. Four primary systems dominate global governance: presidential, parliamentary, federal, and unitary. Each offers distinct advantages and challenges, influencing everything from policy-making speed to regional autonomy.

Understanding these structures is crucial for navigating political landscapes and engaging meaningfully in civic life.

Presidential systems, exemplified by the United States, separate executive and legislative powers. The president, directly elected by the people, serves as both head of state and government, while the legislature operates independently. This separation fosters checks and balances but can lead to gridlock when opposing parties control different branches. For instance, the U.S. Congress and presidency often clash, slowing legislative progress. This system suits nations seeking strong executive leadership and clear accountability but risks polarization and power struggles.

In contrast, parliamentary systems, like those in the United Kingdom and Germany, fuse executive and legislative powers. The head of government, typically a prime minister, is chosen by the legislature, ensuring alignment between the two branches. This structure allows for quicker decision-making and greater flexibility, as governments can fall if they lose legislative support. However, it may lack the stability of fixed terms and can lead to frequent elections in times of political instability. Parliamentary systems thrive in multiparty environments, fostering coalition-building and compromise.

Federal systems, adopted by countries such as India and Brazil, divide power between a central authority and regional governments. This arrangement accommodates diverse populations and geographic expanses by granting states or provinces significant autonomy. While federalism promotes local responsiveness, it can complicate policy implementation and create tensions between national and regional priorities. For example, healthcare policies in the U.S. vary widely by state, reflecting both local needs and ideological differences. Federal systems are ideal for nations with strong regional identities or historical decentralizations.

Unitary systems, prevalent in France and Japan, concentrate power in a single, central government. Local authorities derive their authority from the national level, ensuring uniformity in laws and policies. This structure simplifies governance and enables swift action during crises but may neglect local needs and stifle regional diversity. Unitary systems work best in smaller, more homogeneous countries or those prioritizing national cohesion over regional autonomy.

Choosing a government structure is not a one-size-fits-all decision. Each system reflects historical, cultural, and social contexts, and no model is inherently superior. For instance, a presidential system might suit a nation seeking strong executive leadership, while a federal system could better serve a geographically diverse population. By examining these structures, citizens and leaders can design governance frameworks that balance efficiency, representation, and stability, ultimately fostering more inclusive and responsive political systems.

Understanding Political Lobbying: Influence, Power, and Policy Shaping Explained

You may want to see also

Constitutional Principles: Rule of law, separation of powers, and fundamental rights in governance

The rule of law stands as the bedrock of any constitutional framework, ensuring that no individual or entity stands above the law. It mandates that laws are publicly disclosed, evenly enforced, independently adjudicated, and consistent with international human rights principles. For instance, in countries like Germany, the *Grundgesetz* (Basic Law) explicitly prioritizes the rule of law, allowing citizens to challenge government actions through constitutional complaints. This principle prevents arbitrary governance and fosters trust in institutions. To implement it effectively, governments must ensure transparency in legislation, provide legal aid to vulnerable populations, and regularly audit enforcement agencies for bias or corruption. Without the rule of law, even the most democratic systems risk devolving into tyranny or chaos.

Separation of powers divides governmental authority into distinct branches—typically legislative, executive, and judicial—to prevent the concentration of power. The U.S. Constitution exemplifies this by assigning lawmaking to Congress, enforcement to the President, and interpretation to the Supreme Court. However, this system is not rigid; checks and balances allow branches to limit each other’s authority, such as Congress’s power to impeach the President or the Supreme Court’s ability to strike down laws. In practice, this principle requires clear delineation of roles, regular inter-branch dialogue, and public scrutiny to prevent overreach. Nations like France, with its semi-presidential system, demonstrate how separation of powers can adapt to different political contexts while maintaining equilibrium.

Fundamental rights serve as the cornerstone of constitutional governance, safeguarding individual liberties against state encroachment. These rights, often enshrined in a bill of rights or constitution, include freedoms of speech, religion, and assembly, as well as protections against discrimination and arbitrary detention. South Africa’s Constitution, for example, guarantees not only civil and political rights but also socioeconomic rights like access to housing and healthcare. To uphold these rights, governments must establish independent human rights commissions, ensure access to justice, and educate citizens on their entitlements. However, balancing collective security with individual freedoms remains a perennial challenge, as seen in debates over surveillance laws or hate speech regulations.

Integrating these principles into governance requires deliberate design and vigilant oversight. Start by codifying them in a written constitution, ensuring clarity and accessibility. Next, establish institutions like constitutional courts or ombudsmen to enforce compliance. Regularly review laws and policies for alignment with these principles, involving civil society in the process. Caution against superficial adoption; merely having a constitution does not guarantee good governance if institutions are weak or corrupt. Finally, foster a culture of accountability through civic education and media freedom. When rule of law, separation of powers, and fundamental rights are intertwined, they create a resilient political framework capable of weathering crises and upholding justice.

Emergencies as Political Tools: How Disasters Shape Global Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Electoral Systems: Voting mechanisms, representation models, and their impact on political outcomes

Electoral systems are the backbone of democratic processes, shaping how votes translate into political power. At their core, these systems comprise voting mechanisms—such as first-past-the-post, proportional representation, or ranked-choice voting—and representation models, which determine how elected officials are allocated to constituencies. The interplay between these elements profoundly influences political outcomes, from party dynamics to policy decisions. For instance, first-past-the-post systems often favor a two-party structure, while proportional representation encourages multi-party systems and coalition governments. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for anyone seeking to analyze or reform democratic institutions.

Consider the practical implications of voting mechanisms. In first-past-the-post systems, used in countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, the candidate with the most votes in a district wins, even if they fall short of a majority. This can lead to "wasted votes" and underrepresentation of smaller parties. In contrast, proportional representation systems, common in Europe, allocate parliamentary seats based on parties' vote shares, ensuring minority voices are heard. Ranked-choice voting, increasingly adopted in local U.S. elections, allows voters to rank candidates, reducing the spoiler effect and promoting consensus-building. Each mechanism carries trade-offs: simplicity versus inclusivity, stability versus diversity.

Representation models further complicate this landscape. Single-member districts, typical in first-past-the-post systems, create direct accountability between constituents and representatives but can marginalize minority groups. Multi-member districts, often paired with proportional representation, foster greater diversity in elected bodies but may dilute local representation. Mixed-member systems, as seen in Germany, combine elements of both, offering a balance between proportionality and constituency ties. The choice of model reflects a society's priorities: Is the goal to mirror demographic diversity, ensure geographic representation, or maximize political stability?

The impact of these systems on political outcomes cannot be overstated. First-past-the-post tends to produce majority governments, enabling swift decision-making but risking polarization. Proportional representation often leads to coalition governments, fostering compromise but sometimes resulting in legislative gridlock. For example, Israel's proportional system has produced frequent elections due to coalition instability, while New Zealand's mixed-member proportional system has balanced representation with governability. These outcomes highlight the need for careful design, as electoral systems are not neutral tools but active shapers of political culture.

To navigate this complexity, reformers and citizens alike must ask critical questions. Does the current system reflect the will of the people, or does it distort it? How can mechanisms be adjusted to enhance fairness without sacrificing efficiency? Practical steps include studying international models, piloting reforms in local elections, and engaging stakeholders in transparent dialogue. For instance, Estonia's e-voting system offers a model for modernizing accessibility, while Ireland's use of ranked-choice voting demonstrates how to encourage cross-party cooperation. Ultimately, the goal is not to find a one-size-fits-all solution but to craft systems that align with a society's values and needs.

Is PBS Politically Biased? Analyzing Public Broadcasting's Neutrality Claims

You may want to see also

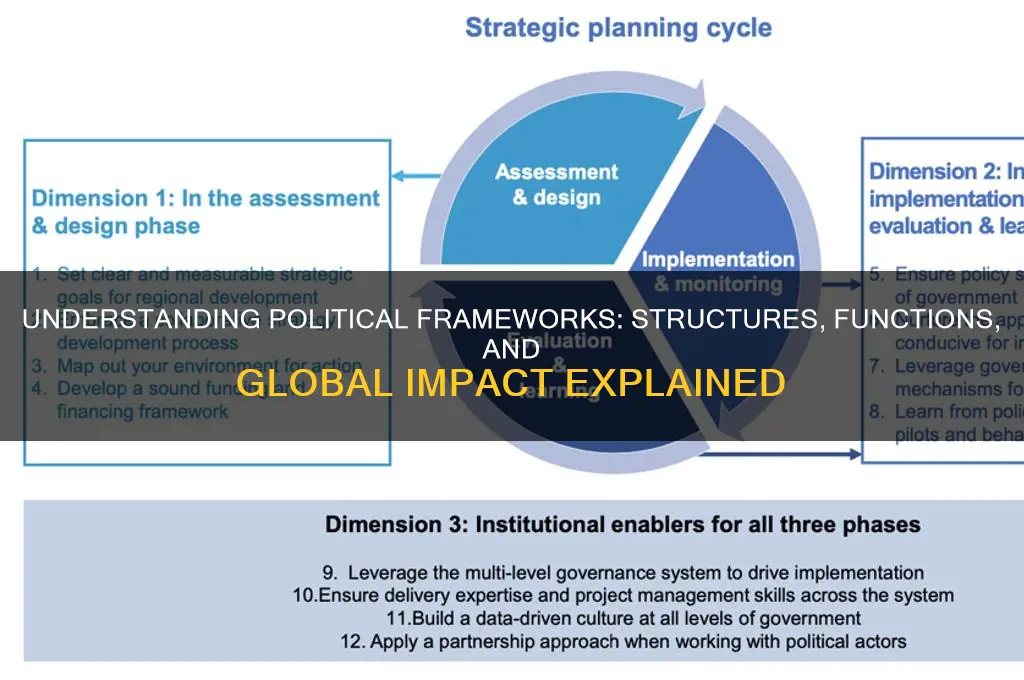

Policy Formulation: Processes, stakeholders, and frameworks for creating and implementing public policies

Policy formulation is the backbone of effective governance, a structured process that transforms societal needs into actionable public policies. At its core, this process involves identifying problems, crafting solutions, and establishing mechanisms for implementation. It is not a linear journey but a dynamic interplay of research, consultation, and decision-making. For instance, consider the formulation of a national healthcare policy. It begins with data collection on health disparities, followed by stakeholder consultations with medical professionals, insurers, and patient groups. This multi-step approach ensures that policies are both evidence-based and responsive to diverse interests.

Stakeholders are the lifeblood of policy formulation, each bringing unique perspectives and priorities to the table. Governments, as primary actors, set the agenda and allocate resources, but their role is far from solitary. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) often provide grassroots insights, while businesses advocate for economic feasibility. Take the example of climate policy: environmental NGOs push for stringent regulations, industries lobby for gradual transitions, and citizens demand immediate action. Balancing these interests requires skillful negotiation and compromise. A practical tip for policymakers is to create inclusive platforms, such as public hearings or online forums, to ensure all voices are heard.

Frameworks serve as the scaffolding for policy formulation, providing structure and consistency. One widely used framework is the Rational Model, which emphasizes systematic problem-solving through clear objectives, data analysis, and cost-benefit assessments. However, this model’s rigidity often clashes with real-world complexities. In contrast, the Incremental Model allows for gradual adjustments, making it suitable for policies requiring flexibility, like education reform. For instance, Finland’s education system evolved incrementally, with small changes tested and scaled over decades. Choosing the right framework depends on the policy’s scope, urgency, and political context.

Implementation is where policies transition from paper to practice, a phase fraught with challenges. Effective implementation requires clear guidelines, adequate funding, and monitoring mechanisms. Consider the rollout of a universal basic income (UBI) policy: it demands precise eligibility criteria, robust IT infrastructure, and regular audits to prevent misuse. A cautionary note: even well-designed policies can fail if implementation is rushed or underfunded. For example, India’s demonetization policy in 2016 suffered from poor execution, leading to economic disruption. Policymakers should adopt a phased approach, starting with pilot programs to identify and address bottlenecks before full-scale implementation.

In conclusion, policy formulation is a complex yet essential process that bridges societal needs with governmental action. By understanding the roles of stakeholders, leveraging appropriate frameworks, and prioritizing meticulous implementation, policymakers can create policies that are both impactful and sustainable. A practical takeaway is to treat policy formulation as an iterative process, continuously refining approaches based on feedback and outcomes. After all, the goal is not just to create policies but to ensure they deliver tangible benefits to the public.

Geography's Grip: Shaping Political Landscapes and Global Power Dynamics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political framework refers to the structured system of principles, rules, institutions, and processes that govern how political power is organized, exercised, and distributed within a society or state.

A political framework is important because it provides stability, ensures the rule of law, defines the relationship between the government and its citizens, and facilitates decision-making and conflict resolution in a society.

The key components of a political framework include the constitution, government institutions (e.g., executive, legislative, judiciary), political parties, electoral systems, and legal mechanisms that regulate political behavior.

A political framework differs across countries based on factors such as historical context, cultural values, and societal needs. Examples include democratic, authoritarian, federal, and unitary systems, each with distinct structures and processes.

Yes, a political framework can change over time through constitutional amendments, political reforms, revolutions, or shifts in societal values. Such changes often reflect evolving needs and aspirations of the population.