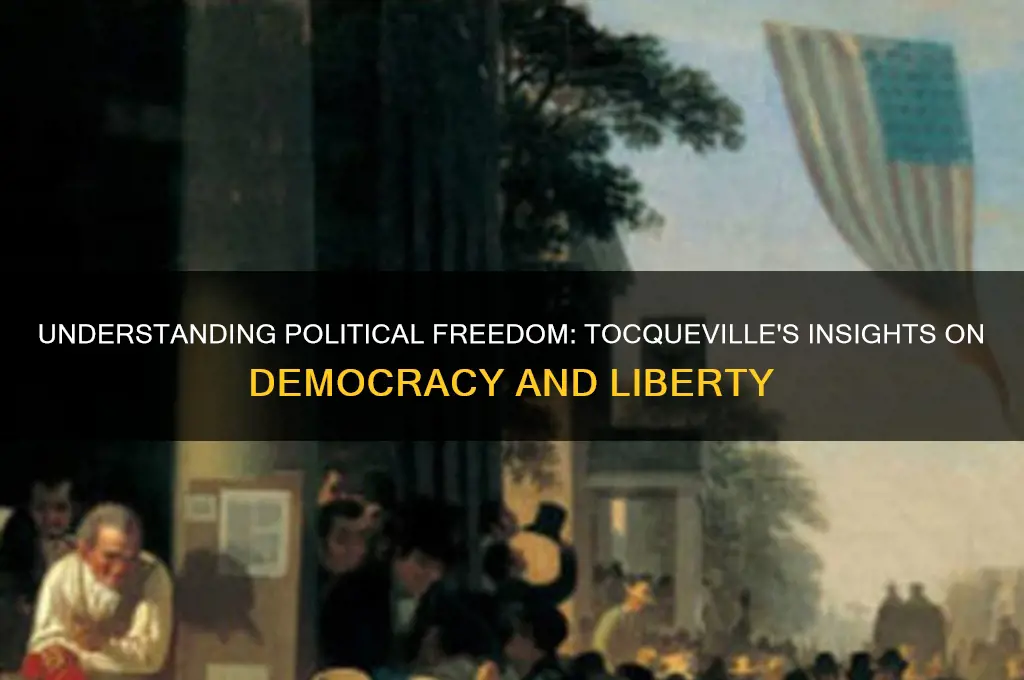

Political freedom, as explored by Alexis de Tocqueville in his seminal work *Democracy in America*, refers to the ability of individuals to participate in self-governance, express their opinions, and pursue their interests without undue interference from the state or other coercive powers. Tocqueville observed that in democratic societies, political freedom is not merely the absence of tyranny but a dynamic interplay between individual liberties and collective decision-making. He highlighted the importance of civic engagement, decentralized institutions, and the balance between majority rule and minority rights in sustaining true political freedom. For Tocqueville, this freedom was both a cornerstone of democracy and a fragile achievement, requiring constant vigilance to prevent its erosion by the tyranny of the majority or the concentration of power. His insights remain profoundly relevant in understanding the complexities of political freedom in modern societies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Political freedom, as discussed by Alexis de Tocqueville, refers to the ability of citizens to participate in the political process, influence government decisions, and enjoy civil liberties without undue interference from the state. |

| Citizen Participation | Active involvement in elections, public debates, and governance. |

| Rule of Law | Equality before the law, protection of individual rights, and prevention of arbitrary power. |

| Decentralization | Distribution of political power across local and regional levels to prevent central authority concentration. |

| Civil Associations | Strong, independent civil society organizations that foster community engagement and counterbalance government power. |

| Freedom of Expression | Unrestricted ability to express opinions, criticize the government, and access information. |

| Equality of Opportunity | Fair access to political participation and representation regardless of social or economic status. |

| Checks and Balances | Separation of powers among branches of government to prevent tyranny and ensure accountability. |

| Local Governance | Empowerment of local communities to manage their affairs and make decisions autonomously. |

| Public Spirit | A sense of civic duty and collective responsibility among citizens to uphold democratic values. |

| Protection of Minorities | Safeguarding the rights and interests of minority groups within the political system. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Democracy and Individual Liberty

In his seminal work *Democracy in America*, Alexis de Tocqueville observed that democracy, while fostering equality, poses a unique threat to individual liberty. He argued that the tyranny of the majority—where the will of the many overwhelms the rights of the few—could stifle personal freedoms. This tension between collective decision-making and individual autonomy remains a central challenge in democratic societies. Tocqueville’s insight prompts a critical question: How can democracies safeguard liberty without sacrificing the principles of majority rule?

To protect individual liberty within a democracy, Tocqueville emphasized the importance of decentralized power and civic engagement. He praised America’s local institutions, such as town meetings and voluntary associations, which empowered citizens to participate directly in governance. These structures, he argued, fostered a sense of responsibility and prevented the concentration of authority in distant, centralized hands. For modern democracies, this suggests a practical strategy: encourage grassroots organizations, community involvement, and local decision-making to counterbalance the potential overreach of national governments.

A comparative analysis of democracies reveals that those with robust constitutional protections and independent judiciaries better preserve individual liberty. Tocqueville noted the role of America’s Constitution in limiting majority power and safeguarding minority rights. Countries like Germany and India, with strong constitutional frameworks, exemplify this approach. Conversely, democracies lacking such checks risk slipping into majoritarianism, where individual freedoms are compromised. For instance, while direct democracy mechanisms like referendums can enhance participation, they must be tempered by legal safeguards to prevent the erosion of rights.

Persuasively, Tocqueville’s warnings about the “soft despotism” of democracy—where citizens trade liberty for security and comfort—resonate in today’s surveillance-driven societies. The rise of data collection, algorithmic decision-making, and state monitoring threatens privacy and autonomy. To counter this, democracies must enact stringent data protection laws, ensure transparency in governance, and educate citizens about their digital rights. Practical steps include advocating for encryption, supporting privacy-focused technologies, and fostering public discourse on the ethical use of technology.

In conclusion, Tocqueville’s exploration of democracy and individual liberty offers timeless lessons for modern societies. By decentralizing power, strengthening constitutional protections, and addressing contemporary threats like digital surveillance, democracies can navigate the delicate balance between collective will and personal freedom. His work reminds us that liberty is not a passive gift of democracy but an active responsibility requiring vigilance, participation, and institutional safeguards.

1984: Orwell's Political Masterpiece or a Dystopian Warning?

You may want to see also

Role of Civil Associations

Civil associations, as Alexis de Tocqueville observed in *Democracy in America*, serve as the bedrock of political freedom by fostering civic engagement and counterbalancing state power. These voluntary groups—ranging from local clubs to national organizations—create spaces where individuals practice self-governance, debate public issues, and collectively address community needs. Tocqueville argued that such associations prevent the tyranny of the majority and individual isolation, both of which threaten democratic vitality. For instance, a neighborhood association advocating for park improvements not only achieves a tangible goal but also teaches members the art of negotiation and compromise, skills essential for democratic participation.

To harness the power of civil associations, consider these actionable steps: first, identify a shared local concern, such as inadequate public transportation or lack of youth programs. Next, convene a small group of stakeholders to define goals and roles, ensuring diverse voices are included. Finally, establish regular meetings and clear decision-making processes to maintain momentum. Caution against over-reliance on charismatic leaders, as this can undermine collective ownership. Instead, rotate responsibilities and encourage all members to contribute ideas, fostering a culture of inclusivity and shared leadership.

A comparative analysis reveals the stark contrast between societies with robust civil associations and those without. In countries like Sweden and Switzerland, high levels of associational life correlate with greater political stability and citizen trust in institutions. Conversely, nations with weak civil society often struggle with centralized authority and civic apathy. For example, during the 2020 U.S. elections, grassroots organizations mobilized millions of voters, demonstrating how civil associations can amplify political participation. This underscores Tocqueville’s insight: a free society depends not just on formal institutions but on the informal networks that bind citizens together.

Persuasively, one could argue that civil associations are not merely optional but necessary for sustaining political freedom. They act as laboratories of democracy, where individuals learn to balance personal interests with the common good. For parents, encouraging children to join youth-led initiatives, such as environmental clubs or student councils, instills early habits of civic responsibility. Similarly, employers can promote workplace associations to empower employees and improve organizational culture. By integrating civil associations into daily life, societies fortify their democratic foundations and ensure that political freedom remains a living practice, not an abstract ideal.

Trump's Political Background: Assessing His Experience in Governance and Leadership

You may want to see also

Tyranny of the Majority

In democratic societies, the will of the majority often reigns supreme, but this very principle can sow the seeds of oppression. Alexis de Tocqueville, in his seminal work *Democracy in America*, warns of the "Tyranny of the Majority"—a phenomenon where the dominant group imposes its preferences on minorities, stifling dissent and individuality. This concept remains eerily relevant in modern politics, where majority rule can sometimes eclipse the rights of the few.

Consider the mechanics of this tyranny: when a majority wields unchecked power, it can marginalize dissenting voices, not through overt force but through the subtle erosion of freedoms. For instance, in legislative bodies, majority coalitions may pass laws that favor their interests while disregarding the needs of smaller groups. This isn’t merely about winning votes; it’s about the danger of homogenizing society under a single, dominant perspective. Tocqueville observed that such a system risks creating a "mild despotism," where citizens are free in theory but conformist in practice, fearing social or political repercussions for deviating from the majority’s norms.

To combat this, Tocqueville emphasizes the importance of institutional safeguards. He highlights the role of an independent judiciary, free press, and decentralized governance in balancing majority power. For example, constitutional protections for minority rights act as a firewall against majoritarian overreach. In practical terms, this could mean advocating for stronger anti-discrimination laws or ensuring that electoral systems represent diverse voices, not just the loudest ones.

Yet, the challenge extends beyond institutions. Cultural attitudes play a pivotal role. Encouraging a society that values pluralism and tolerates dissent is crucial. This involves fostering education systems that teach critical thinking and empathy, rather than conformity. Parents, educators, and policymakers can promote this by integrating diverse perspectives into curricula and public discourse, ensuring that minority viewpoints are not silenced but celebrated as essential to a healthy democracy.

Ultimately, the Tyranny of the Majority serves as a cautionary tale for democracies. It reminds us that true political freedom isn’t just about majority rule but about protecting the rights of all citizens. By implementing structural checks and nurturing a culture of inclusivity, societies can guard against this insidious form of oppression, ensuring that democracy remains a force for liberation, not domination.

Do Political Postcards Sway Voters? Analyzing Their Campaign Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Decentralization of Power

To implement decentralization effectively, governments must adopt a multi-step approach. First, devolve fiscal authority to local bodies, ensuring they have the resources to address community-specific issues. Second, establish clear legal frameworks that define the roles and responsibilities of each governance tier, minimizing overlap and conflict. Third, promote transparency and accountability through regular audits and public reporting mechanisms. Caution must be exercised to avoid creating power vacuums or enabling local corruption. For example, in countries like India, decentralization through the Panchayati Raj system has empowered villages but also exposed vulnerabilities in oversight and resource allocation.

A persuasive argument for decentralization lies in its ability to enhance political participation and reduce alienation. When power is centralized, citizens often feel disconnected from the decision-making process, leading to apathy or discontent. Decentralization, however, brings governance closer to the people, making it more accessible and responsive. Consider the Swiss canton system, where local autonomy is deeply ingrained, resulting in high voter turnout and a strong sense of civic duty. This model demonstrates that when individuals see the direct impact of their involvement, they are more likely to engage meaningfully in the political process.

Comparatively, centralized systems often struggle to address diverse societal needs efficiently. For instance, while China’s centralized governance has enabled rapid infrastructure development, it has also led to widespread discontent in regions like Xinjiang and Tibet, where local cultures and priorities are overlooked. In contrast, decentralized systems, such as those in Germany or Canada, allow for tailored policies that respect regional differences. This adaptability not only fosters unity but also ensures that political freedom is experienced equally across all segments of society, regardless of geography or culture.

Finally, decentralization serves as a practical safeguard against tyranny and overreach. By fragmenting power, it creates checks and balances that prevent any single authority from dominating. Tocqueville’s analysis of American democracy highlights how this fragmentation encouraged a vibrant civil society, where citizens organized into voluntary associations to address common concerns. Today, this principle remains relevant, especially in the digital age, where centralized control over information and technology poses new threats to freedom. Decentralized systems, whether in governance or technology, offer a resilient framework for protecting individual rights and ensuring that political freedom endures.

Mastering the Art of Trolling Political Texts: Tips and Tricks

You may want to see also

Equality vs. Freedom Balance

Alexis de Tocqueville, in his seminal work *Democracy in America*, observed that the United States in the 19th century grappled with a delicate equilibrium between equality and freedom. He noted that while Americans prized individual liberty, their commitment to equality often led to a form of "soft despotism"—a majority rule that could stifle dissent and homogenize thought. This tension remains a central challenge in modern democracies, where the pursuit of equality can inadvertently curtail freedoms, and the defense of freedom can exacerbate inequalities.

Consider the practical dilemma of affirmative action policies. Designed to redress historical injustices and promote equality, these measures often involve restrictions on individual freedoms, such as merit-based selection in education or employment. Critics argue that such policies infringe on the freedom to compete fairly, while proponents contend that they are necessary to dismantle systemic barriers. Tocqueville would likely caution that while equality is a noble goal, its pursuit must not undermine the foundational freedoms that sustain democratic vitality.

A comparative analysis of Scandinavian countries versus libertarian societies like Hong Kong reveals contrasting approaches to this balance. Nordic nations prioritize equality through robust welfare systems, high taxation, and collective bargaining, often at the expense of economic freedom. In contrast, Hong Kong’s low-tax, laissez-faire model maximizes individual economic liberty but struggles with stark income inequality. Neither system is perfect, but they illustrate the trade-offs inherent in prioritizing one value over the other.

To strike a balance, policymakers should adopt a layered approach. First, define the scope of equality: is it equality of opportunity or outcome? Second, establish safeguards for minority rights and free expression to prevent majoritarian overreach. Third, encourage decentralized decision-making, as Tocqueville admired in American townships, where local communities can tailor solutions to their unique needs. Finally, foster a culture of civic engagement, where citizens actively debate and negotiate the boundaries between equality and freedom.

In practice, this might mean implementing targeted policies like universal basic income to address inequality without stifling entrepreneurship, or creating independent media councils to protect free speech from both state and corporate influence. The key is to recognize that equality and freedom are not zero-sum; they are interdependent pillars of a healthy democracy. As Tocqueville warned, neglecting either risks eroding the very foundations of political liberty.

Understanding Mansfield Politics: A Comprehensive Guide for Engaged Citizens

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

According to Alexis de Tocqueville, political freedom refers to the ability of individuals to participate in self-governance, exercise their rights, and influence political decisions within a democratic framework. It involves both individual liberties and collective participation in the political process.

Tocqueville sees political freedom as the cornerstone of democracy. He argues that democracy thrives when citizens are free to express their opinions, organize, and participate in public affairs, ensuring that power remains decentralized and accountable to the people.

Tocqueville emphasizes that civil associations—such as clubs, societies, and community groups—are vital for political freedom. They foster civic engagement, educate citizens, and act as a buffer against government tyranny, thereby strengthening democratic institutions.

Yes, Tocqueville acknowledged that political freedom must be balanced with order and responsibility. He warned of the "tyranny of the majority," where unchecked democratic power could infringe on individual rights, and stressed the importance of institutions and norms to protect freedoms.