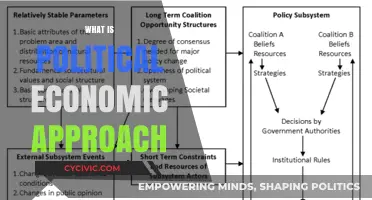

Political economy of media is a critical framework that examines the relationship between media systems, economic structures, and political power. It explores how media institutions are shaped by ownership, funding, and market forces, as well as how they, in turn, influence political processes, public opinion, and societal norms. By analyzing the interplay between capitalism, state policies, and media production, this approach uncovers the underlying mechanisms that determine what content is created, distributed, and consumed. It also highlights issues of inequality, censorship, and the concentration of media power, offering insights into how media functions as both a reflection and a tool of broader socio-economic and political systems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Focus | Examines the relationship between politics, economics, and media systems. |

| Key Concepts | Power, ownership, control, ideology, and representation. |

| Theoretical Roots | Marxism, critical theory, political economy of communication. |

| Media Ownership | Highlights concentration of media ownership in the hands of a few elites. |

| Political Influence | Analyzes how political actors shape media narratives and policies. |

| Economic Determinism | Argues that economic structures influence media content and distribution. |

| Ideological Role | Views media as a tool for reproducing dominant ideologies. |

| Global Perspective | Considers the impact of globalization on media and power dynamics. |

| Criticism of Commercialization | Challenges the commodification of media and its effects on public interest. |

| Alternative Media | Advocates for non-corporate, community-based media as a counterbalance. |

| Policy Implications | Informs policies on media regulation, diversity, and democratization. |

| Contemporary Issues | Addresses digital platforms, algorithmic bias, and media monopolies. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Media Ownership & Control: Examines who owns media outlets and how it influences content and narratives

- Media Regulation & Policy: Explores government policies shaping media operations, censorship, and freedom of expression

- Media & Power Dynamics: Analyzes how media reflects, reinforces, or challenges political and economic power structures

- Media Markets & Capitalism: Investigates the role of profit motives in media production and distribution

- Media as a Public Good: Discusses media’s role in democracy, civic engagement, and access to information

Media Ownership & Control: Examines who owns media outlets and how it influences content and narratives

Media ownership is concentrated in the hands of a few powerful corporations, a trend that has intensified over the past few decades. For instance, in the United States, just five companies—Comcast, Disney, AT&T, Paramount Global, and Fox Corporation—control the majority of broadcast and cable networks, film studios, and streaming platforms. This consolidation raises critical questions about the diversity of voices and perspectives in the media landscape. When a handful of entities dominate the industry, the risk of homogenized content and suppressed narratives increases, as these corporations often prioritize profit over public interest.

Consider the influence of ownership on editorial decisions. A media outlet owned by a conglomerate with ties to specific industries or political parties is more likely to produce content that aligns with those interests. For example, a news network owned by a corporation with significant investments in fossil fuels may downplay climate change stories or frame them in a way that minimizes corporate responsibility. This subtle manipulation of narratives can shape public opinion, often without the audience’s awareness. To counteract this, audiences should actively seek out media literacy tools, such as fact-checking websites and ownership transparency reports, to better understand the biases behind the content they consume.

The impact of media ownership extends beyond news to entertainment, where it can reinforce cultural norms and stereotypes. Major studios and streaming platforms, often owned by the same conglomerates, have the power to decide which stories get told and which remain untold. For instance, the underrepresentation of marginalized communities in film and television is not merely a creative choice but a reflection of systemic biases within the industry. By controlling production budgets, distribution channels, and marketing strategies, media owners can dictate which narratives gain visibility, perpetuating inequality in the process.

To mitigate the effects of concentrated media ownership, regulatory measures and public advocacy play a crucial role. Policies such as antitrust laws and ownership caps can prevent further consolidation, while public funding for independent media can support diverse voices. Audiences, too, have a part to play by diversifying their media consumption and supporting outlets that prioritize transparency and accountability. Ultimately, understanding the relationship between ownership and content is essential for fostering a media environment that serves the public good rather than private interests.

Mastering Office Politics: Strategies for Success and Career Advancement

You may want to see also

Media Regulation & Policy: Explores government policies shaping media operations, censorship, and freedom of expression

Media regulation and policy are the invisible hands that shape the flow of information in any society. Governments worldwide wield these tools to control media operations, often under the guise of maintaining order, protecting national interests, or safeguarding public morality. For instance, China’s Great Firewall is a prime example of state-driven censorship, blocking access to foreign news outlets and social media platforms to curb dissent and control the narrative. Such policies raise critical questions about the balance between state authority and individual freedoms, particularly in the digital age where information transcends borders.

Consider the steps governments take to regulate media: licensing requirements, content restrictions, and ownership limits. In the United Kingdom, Ofcom enforces broadcasting standards, ensuring media outlets adhere to fairness and accuracy. Conversely, in countries like Turkey, media ownership is concentrated in the hands of pro-government entities, stifling independent journalism. These measures, while often justified as necessary for societal stability, can also serve as tools for political control. For media practitioners, understanding these regulatory frameworks is essential to navigate legal boundaries and advocate for press freedom.

A comparative analysis reveals stark differences in media regulation across democracies and authoritarian regimes. In the United States, the First Amendment protects freedom of expression, though debates persist over issues like hate speech and misinformation. Meanwhile, in Russia, laws criminalizing "fake news" have been used to silence critics of the government. Such disparities highlight the tension between state power and democratic ideals. For policymakers, striking a balance requires careful consideration of cultural contexts and the evolving nature of media technologies.

Practical tips for journalists and media organizations operating in regulated environments include: first, familiarize yourself with local media laws and their enforcement mechanisms. Second, leverage international networks and platforms to amplify stories that might be censored domestically. Third, invest in digital security to protect sources and data from state surveillance. Finally, engage in advocacy efforts to push for more transparent and inclusive media policies. These strategies can help mitigate the risks of censorship while upholding the principles of free expression.

The takeaway is clear: media regulation and policy are not neutral instruments but reflections of political and ideological priorities. While some measures aim to foster accountability and diversity in media, others serve to suppress dissent and consolidate power. As media landscapes continue to evolve, so too must the frameworks that govern them. Stakeholders—from journalists to policymakers—must remain vigilant in ensuring that regulation enhances, rather than undermines, the role of media as a pillar of democracy.

Understanding Political Independence: What Does It Truly Mean in Modern Governance?

You may want to see also

Media & Power Dynamics: Analyzes how media reflects, reinforces, or challenges political and economic power structures

Media ownership is concentrated in the hands of a few conglomerates, a fact that shapes the very fabric of our information landscape. This consolidation of power allows these entities to dictate narratives, prioritize certain stories over others, and ultimately influence public perception. For instance, a study by the Media Ownership Monitor found that in many countries, a handful of companies control the majority of television, radio, and print media outlets. This concentration of ownership often leads to a homogenization of content, where diverse perspectives are marginalized in favor of those that align with the interests of the owning entities.

Consider the role of media in election campaigns. News outlets, both traditional and digital, have the power to frame political candidates and their policies in ways that can significantly impact voter behavior. A study by the Pew Research Center revealed that media coverage can influence public opinion by highlighting specific aspects of a candidate's platform while downplaying others. For example, during the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the media's focus on email controversies overshadowed policy discussions, potentially altering the course of the election. This demonstrates how media can reinforce existing power structures by amplifying certain narratives while silencing others.

However, media is not always a passive reflector of power dynamics; it can also challenge and disrupt them. Social media platforms, in particular, have democratized the dissemination of information, allowing marginalized voices to gain visibility and challenge dominant narratives. The #MeToo movement, for instance, gained momentum through social media, bypassing traditional gatekeepers and forcing a global conversation on issues of sexual harassment and assault. This shift in power dynamics highlights the potential of media to act as a counterbalance to established political and economic structures.

To effectively analyze media's role in power dynamics, one must adopt a critical lens. Start by examining the funding sources of media outlets, as these often dictate editorial priorities. For example, media organizations reliant on advertising revenue may avoid criticizing corporations that are major advertisers. Next, analyze the diversity of voices represented in media content. A lack of representation from certain demographics can perpetuate systemic inequalities. Finally, consider the historical context of media ownership and its evolution over time. Understanding these factors provides a comprehensive view of how media reflects, reinforces, or challenges power structures.

In practical terms, individuals can take steps to navigate this complex landscape. Diversify your sources of information by consuming media from a variety of outlets, including independent and international sources. Engage critically with content by questioning the underlying assumptions and biases. Support media literacy initiatives that empower individuals to analyze and evaluate information effectively. By doing so, you contribute to a more informed and equitable media environment, one that challenges rather than reinforces existing power dynamics.

Is Bombshell a Political Movie? Analyzing Its Themes and Impact

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Media Markets & Capitalism: Investigates the role of profit motives in media production and distribution

The media landscape is a battleground where profit motives wield significant influence, shaping not only what content gets produced but also how it's distributed and consumed. This dynamic is at the heart of the political economy of media, a critical lens through which we examine the intricate relationship between media markets and capitalism.

The Profit Imperative: Media organizations, from traditional news outlets to streaming giants, operate within a capitalist framework where profitability is paramount. This imperative drives decision-making at every stage of media production and distribution. Consider the following scenario: a news network faces a choice between investing in an investigative journalism piece exposing corporate malfeasance or producing a sensationalist reality TV show. The latter, with its potential for higher viewership and advertising revenue, often wins out, illustrating how profit motives can distort media priorities.

Market Forces and Content Creation: In a capitalist media market, content is a commodity, and its value is determined by market forces. This reality has several implications. First, media producers tend to cater to the tastes and preferences of the largest, most lucrative audiences, often resulting in a homogenization of content. For instance, Hollywood blockbusters frequently rely on proven formulas, sequels, and remakes to minimize financial risk. Second, niche markets may be underserved as media companies prioritize mass appeal. Independent filmmakers, documentary producers, and journalists covering specialized topics often struggle to secure funding, highlighting the challenges of operating outside the mainstream.

Advertising and the Attention Economy: The role of advertising in media is a critical aspect of this discussion. Media outlets often rely on advertising revenue, which creates a symbiotic relationship between media companies and advertisers. This relationship can lead to a subtle (or not so subtle) influence on content. For example, news websites might design their platforms to maximize user engagement, keeping readers on the site longer to increase ad exposure. This 'attention economy' prioritizes clickbait headlines and sensational content over more substantive but less immediately engaging material. As a result, media consumers are often bombarded with content designed to capture attention rather than inform or educate.

Monopolies and Media Ownership: Capitalism's tendency towards market concentration is evident in media ownership patterns. Media conglomerates, through mergers and acquisitions, have created vast empires that control multiple platforms and outlets. This consolidation reduces competition and can limit the diversity of voices in the media landscape. For instance, a single corporation owning a newspaper, a TV network, and several radio stations in a particular region can exert significant influence over public opinion, potentially marginalizing alternative viewpoints.

Navigating the Media Landscape: Understanding the profit-driven nature of media markets is essential for media literacy. Consumers should be aware of the underlying motivations that shape the content they engage with. This awareness encourages a more critical approach to media consumption, prompting questions like: Who owns this media outlet? What are their potential biases? How might advertising influence the narrative? By recognizing the role of capitalism in media, individuals can make more informed choices, supporting independent media, seeking diverse perspectives, and advocating for policies that promote media pluralism and accountability.

In the complex interplay between media markets and capitalism, the pursuit of profit can both drive innovation and distort the media's role as a public good. Recognizing these dynamics is crucial for anyone seeking to understand the modern media environment and its impact on society.

Empowering Democracy: Nonprofits' Role in Boosting Political Engagement

You may want to see also

Media as a Public Good: Discusses media’s role in democracy, civic engagement, and access to information

Media, when treated as a public good, serves as the lifeblood of democratic societies. Unlike commodities, public goods are non-excludable and non-rivalrous, meaning everyone can access them without diminishing their availability for others. In this context, media’s role is to provide unbiased information, foster civic engagement, and hold power accountable. For instance, public service broadcasters like the BBC or NPR exemplify this model, offering news and educational content free from commercial pressures. Such institutions ensure that citizens, regardless of socioeconomic status, have access to the knowledge necessary for informed participation in democracy.

Consider the mechanics of civic engagement: media acts as a bridge between governments and citizens, translating complex policies into digestible formats. Investigative journalism, a cornerstone of this function, uncovers truths that might otherwise remain hidden. The *Panama Papers*, a collaborative effort by international journalists, exposed global tax evasion, sparking public outrage and policy reforms. This demonstrates how media, as a public good, amplifies transparency and empowers citizens to demand accountability. Without such access, democracy risks becoming a hollow structure, devoid of meaningful participation.

However, treating media as a public good requires deliberate policy interventions. Commercialization and privatization often skew content toward profit-driven narratives, marginalizing underserved communities. Governments must invest in media infrastructure, subsidize independent outlets, and enforce regulations that prioritize public interest over corporate gain. For example, Norway’s media support system provides grants to small newspapers and digital platforms, ensuring diverse voices thrive. Such measures are not just beneficial—they are essential for countering misinformation and fostering inclusive discourse.

A cautionary tale emerges from countries where media is treated solely as a commodity. In the U.S., the decline of local journalism has created "news deserts," leaving communities uninformed about local governance. This vacuum is often filled by partisan outlets or social media, exacerbating polarization. Conversely, Finland’s approach, which ranks highest in global press freedom, combines robust public funding with media literacy education. This dual strategy ensures citizens not only access information but also critically evaluate it, strengthening democratic resilience.

In practice, individuals can advocate for media as a public good by supporting non-profit news organizations, participating in public forums, and demanding transparency from policymakers. For instance, subscribing to *ProPublica* or *The Guardian* sustains investigative journalism. Schools and communities can integrate media literacy programs, teaching younger generations to discern credible sources from disinformation. Ultimately, media’s role as a public good is not a given—it requires collective effort to protect and expand its democratic function. Without it, the very foundations of informed citizenship and accountability are at risk.

Your Guide to Entering Politics in New Zealand: Tips and Strategies

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political economy of media is an interdisciplinary approach that examines the relationship between politics, economics, and media systems. It explores how power, ownership, and market forces shape media production, distribution, and consumption, as well as their impact on society and democracy.

The political economy of media is important because it helps us understand how media industries are influenced by political and economic structures. It highlights issues like media concentration, corporate influence, and the role of governments in regulating or controlling media, which are critical for assessing media’s role in public discourse and democracy.

Key concepts include media ownership, market structures, regulation, commodification of content, and the role of global media conglomerates. It also examines how these factors affect media diversity, representation, and the balance of power between media producers, consumers, and political entities.