The political economic approach is a multidisciplinary framework that examines the interplay between politics, economics, and power in shaping societal outcomes. It explores how political institutions, economic systems, and power structures influence resource distribution, policy-making, and social inequalities. By integrating insights from political science, economics, sociology, and history, this approach critiques traditional economic models that often overlook the role of political power and historical context. It highlights how economic policies are not neutral but are shaped by the interests of dominant groups, and how these policies, in turn, reinforce or challenge existing power dynamics. This perspective is particularly valuable for understanding issues such as globalization, inequality, development, and the role of the state in the economy, offering a more nuanced and critical analysis of the complex relationships between politics and economics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Interdisciplinary Focus | Combines principles from politics, economics, sociology, and history. |

| Power Dynamics | Analyzes how power relations influence economic policies and outcomes. |

| Class and Inequality | Examines the role of class structures and income inequality in societies. |

| State and Market Interaction | Studies the relationship between government intervention and market forces. |

| Historical Context | Considers historical events and structures to understand current systems. |

| Global and Local Perspectives | Explores how global economic systems impact local economies and vice versa. |

| Critical of Mainstream Economics | Challenges neoclassical economics by emphasizing social and political factors. |

| Institutional Analysis | Focuses on the role of institutions (e.g., laws, norms) in shaping economies. |

| Conflict and Cooperation | Investigates conflicts and collaborations between different economic actors. |

| Policy and Governance | Evaluates how political decisions shape economic policies and governance. |

| Social Justice and Equity | Prioritizes fairness, equity, and the distribution of resources. |

| Cultural and Ideological Factors | Considers how culture and ideology influence economic behavior and policies. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- State-Market Relations: Examines interactions between government and private sectors in resource allocation and policy-making

- Power Dynamics: Analyzes how economic systems shape and are shaped by political power structures

- Class and Inequality: Explores economic disparities and their political implications on society and governance

- Globalization Impacts: Studies how global economic integration affects national political economies and sovereignty

- Institutional Frameworks: Investigates the role of institutions in mediating political and economic outcomes

State-Market Relations: Examines interactions between government and private sectors in resource allocation and policy-making

The relationship between the state and the market is a delicate dance, where each partner's moves influence the rhythm of resource allocation and policy outcomes. In the political economic approach, this interplay is a central focus, offering a lens to understand how societies distribute power, wealth, and opportunities. At its core, this perspective asks: How do governments and private entities negotiate their roles in shaping economic landscapes?

The Art of Negotiation: A Case Study

Imagine a country's healthcare sector, where the government aims to ensure universal access, while private companies seek profitable ventures. The state might propose a policy mandating a minimum number of affordable treatment options in every hospital, a move that could potentially reduce corporate profits. Here, the negotiation begins. Private sector representatives may argue for tax incentives to offset these costs, while the government weighs the benefits of a healthier population against potential revenue losses. This scenario illustrates the constant dialogue and compromise inherent in state-market relations.

Analyzing the Power Dynamics

In this dynamic, power is not solely determined by economic might. Governments possess regulatory authority, which can be a double-edged sword. Over-regulation may stifle innovation and drive businesses away, while under-regulation could lead to market failures and social inequalities. For instance, environmental policies often require industries to adopt cleaner technologies, a decision that can significantly impact production costs. Here, the state's role is to balance ecological sustainability with economic viability, a task that requires constant engagement with market players.

A Comparative Perspective: Varied Approaches

Different political-economic systems offer diverse strategies for managing these relations. In a social democratic model, the state actively intervenes to reduce market inequalities, often through progressive taxation and robust welfare systems. Contrastingly, a neoliberal approach advocates for minimal state interference, emphasizing market freedom and individual responsibility. Each system's unique approach to state-market relations shapes societal outcomes, influencing factors like income distribution, social mobility, and economic growth rates.

Practical Implications and Strategies

Understanding this relationship is crucial for policymakers and businesses alike. For governments, it involves crafting policies that encourage market efficiency while addressing societal needs. This might include offering subsidies for research and development in strategic sectors or implementing competition laws to prevent monopolies. Businesses, on the other hand, can engage in corporate social responsibility initiatives, not just as a moral obligation but as a strategic move to align with state priorities and gain public support.

In essence, the political economic approach to state-market relations provides a framework to navigate the complex web of interests and influences. It encourages a nuanced understanding of how these interactions shape the economic and social fabric of societies, offering insights that are both theoretically rich and practically applicable. By studying these dynamics, we can better appreciate the art of governance and the intricate balance required for sustainable development.

Unapologetic Resistance: Why Some Choose Not to Protest Politely

You may want to see also

Power Dynamics: Analyzes how economic systems shape and are shaped by political power structures

Economic systems are not neutral frameworks; they are battlegrounds where political power is both wielded and contested. Consider the global supply chain: multinational corporations, often headquartered in wealthy nations, dictate terms to suppliers in developing countries, perpetuating unequal exchanges of labor and resources. This dynamic illustrates how economic structures—like trade agreements or corporate policies—are tools that reinforce political dominance. Conversely, political entities use economic levers, such as tariffs or subsidies, to consolidate control or punish adversaries. The interplay is cyclical: economic systems create power imbalances, which political actors then exploit to further entrench those systems.

To dissect this relationship, examine the role of institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or World Bank. These organizations, ostensibly neutral, impose structural adjustment programs on indebted nations, often requiring austerity measures that disproportionately harm the poor. Such policies are not merely economic; they are political acts that reshape governance, labor rights, and social welfare. The takeaway is clear: economic systems are not just about resource allocation—they are mechanisms of control, designed and manipulated by those in power to maintain their dominance.

A comparative lens reveals how this dynamic varies across contexts. In authoritarian regimes, economic policies are often explicitly designed to reward loyalists and suppress dissent, as seen in state-controlled industries in countries like Russia or China. In contrast, democratic systems may mask power dynamics under the guise of free markets, where lobbying and corporate influence skew policies in favor of the wealthy. For instance, tax codes in the U.S. often favor corporations over small businesses, illustrating how economic systems are shaped by political power, even in ostensibly egalitarian frameworks.

To challenge these dynamics, one must adopt a critical, interdisciplinary approach. Start by mapping the flow of capital and resources within a given system, identifying choke points where power is concentrated. For example, analyze how land ownership patterns in rural areas perpetuate political control by elites. Next, trace the historical evolution of these systems to uncover how past political decisions—like colonial resource extraction—still shape contemporary economies. Finally, advocate for transparency and accountability in economic institutions, pushing for reforms that decentralize power and prioritize equity.

The ultimate goal is not just to understand these dynamics but to disrupt them. Practical steps include supporting grassroots movements that challenge corporate monopolies, advocating for progressive taxation, and demanding international regulations that curb exploitative practices. By recognizing how economic systems and political power are intertwined, individuals and organizations can work toward creating structures that serve the many, not the few. This is not merely an academic exercise—it is a call to action for a more just and equitable world.

Lady Gaga's Political Influence: Activism, Advocacy, and Cultural Impact

You may want to see also

Class and Inequality: Explores economic disparities and their political implications on society and governance

Economic disparities are not merely gaps in wealth; they are fault lines that shape political landscapes and societal stability. The political economic approach dissects how class divisions—rooted in income, assets, and access to resources—translate into unequal political power. For instance, in the United States, the top 1% of earners hold nearly 20% of the nation's income, a disparity mirrored in campaign contributions and policy influence. This concentration of wealth enables elite groups to sway legislation, from tax codes to labor regulations, often at the expense of lower-income brackets. Such imbalances erode democratic principles, as political representation becomes skewed toward those with financial clout, leaving marginalized communities with diminished agency.

Consider the mechanics of this power dynamic: wealth buys access to policymakers, funds lobbying efforts, and shapes media narratives. In countries like Brazil, where the richest 10% control over 55% of the nation's wealth, political parties reliant on corporate funding often prioritize profit-driven agendas over public welfare. This systemic bias perpetuates inequality, as policies favoring the affluent—such as tax breaks for corporations—exacerbate the wealth gap. Conversely, initiatives like progressive taxation or universal healthcare, which could mitigate disparities, are frequently stalled or diluted due to elite resistance. The takeaway is clear: economic inequality is not a passive byproduct of capitalism but an active force shaping governance.

To address these disparities, a multi-pronged strategy is essential. First, transparency reforms can curb the influence of money in politics, such as public financing of elections or stricter disclosure laws for lobbying activities. Second, redistributive policies—like higher marginal tax rates or inheritance taxes—can reduce wealth concentration. For example, Sweden’s 57% top income tax rate, combined with robust social safety nets, has fostered greater economic equality without stifling growth. Third, empowering labor unions and raising minimum wages can restore bargaining power to workers, as seen in Denmark, where unionization rates exceed 65%, ensuring fair wages and workplace protections.

However, implementing such measures requires navigating political and cultural hurdles. Elites often frame redistributive policies as threats to economic freedom, leveraging media and think tanks to shape public opinion. For instance, the term “trickle-down economics” has been used to justify tax cuts for the wealthy, despite evidence of their ineffectiveness in reducing inequality. Countering this narrative demands grassroots mobilization and education, as exemplified by movements like Occupy Wall Street or Chile’s 2019 protests, which spotlighted the link between economic injustice and political corruption. Without public pressure, even well-designed policies risk being co-opted or abandoned.

Ultimately, the political economic approach reveals that class and inequality are not abstract concepts but lived realities with tangible consequences. Societies that ignore these disparities risk deepening social fractures, as seen in the rise of populist movements fueled by economic discontent. Conversely, those that confront inequality head-on—through equitable policies and inclusive governance—can foster stability and shared prosperity. The challenge lies in translating this awareness into action, ensuring that economic systems serve all citizens, not just the privileged few.

Are Political Ideologies Personal Choices or Collective Identities?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Globalization Impacts: Studies how global economic integration affects national political economies and sovereignty

Global economic integration, driven by globalization, has reshaped the boundaries of national political economies, often blurring the lines between domestic and international spheres. One striking example is the rise of multinational corporations (MNCs) that wield economic power rivaling that of nation-states. For instance, Apple Inc.’s annual revenue exceeds the GDP of many countries, including Portugal and New Zealand. This shift underscores how global economic forces can influence national policies, as governments compete to attract foreign investment by offering tax incentives or relaxing labor regulations. Such dynamics highlight the tension between economic growth and the erosion of state sovereignty.

Analyzing the impact of globalization on political economies reveals a dual-edged sword. On one hand, integration into global markets has lifted millions out of poverty, particularly in emerging economies like China and India. On the other hand, it has exacerbated inequality within nations, as wealth concentrates in the hands of a few. Take the case of Mexico post-NAFTA: while exports surged, small-scale farmers were displaced by subsidized American agricultural products, illustrating how global trade agreements can disproportionately benefit certain sectors while marginalizing others. This imbalance challenges policymakers to balance economic liberalization with social equity.

To navigate these complexities, nations must adopt strategic measures. First, diversifying their economies reduces dependency on a single global market or commodity. For example, Malaysia’s transition from reliance on tin and rubber to electronics manufacturing and services has bolstered its resilience. Second, investing in education and technology equips the workforce to compete in a globalized economy. Germany’s vocational training system, which aligns skills with industry needs, serves as a model. Lastly, fostering regional trade blocs, like the African Continental Free Trade Area, can amplify collective bargaining power on the global stage.

A cautionary tale emerges from countries that have failed to adapt to globalization’s pressures. Greece’s economic crisis in the 2010s, exacerbated by its integration into the Eurozone without sufficient fiscal reforms, demonstrates the risks of unpreparedness. Similarly, Argentina’s recurring debt crises reflect the dangers of over-reliance on foreign capital without robust domestic institutions. These cases emphasize the need for proactive governance, including transparent fiscal policies and regulatory frameworks that safeguard national interests while engaging with global markets.

In conclusion, the political economic approach to globalization impacts demands a nuanced understanding of its interplay with national sovereignty. By examining concrete examples and adopting practical strategies, nations can harness the benefits of global integration while mitigating its drawbacks. The challenge lies in striking a balance between openness and autonomy, ensuring that economic globalization serves as a tool for inclusive development rather than a force of disempowerment.

Do Morals Belong in Politics? Exploring Ethics and Governance

You may want to see also

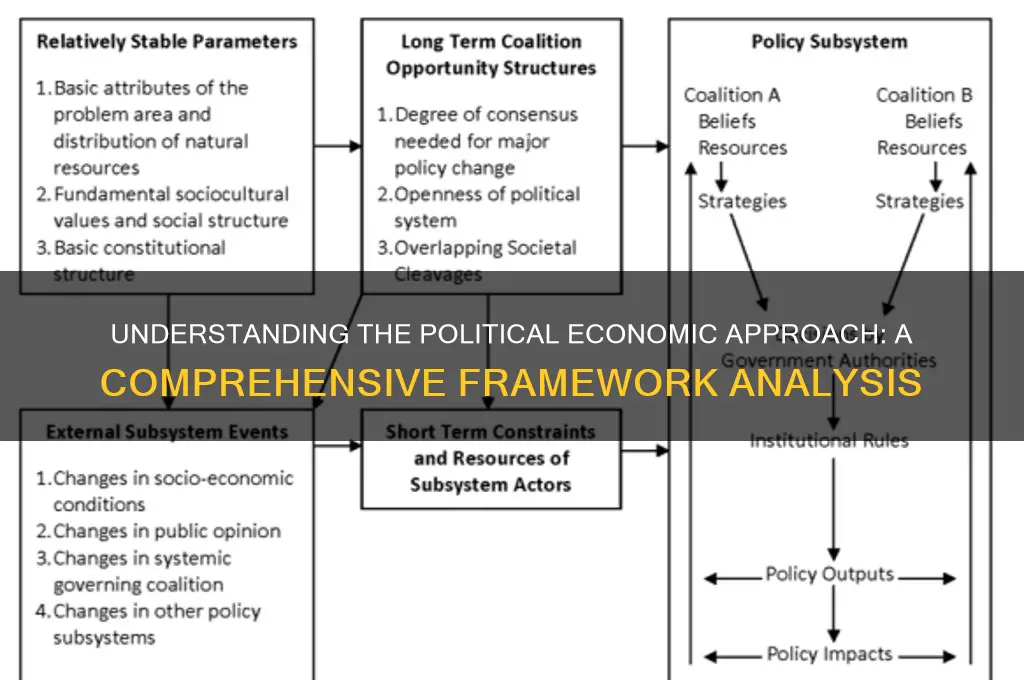

Institutional Frameworks: Investigates the role of institutions in mediating political and economic outcomes

Institutions, as the rules of the game in any society, shape how political and economic forces interact. They are not neutral arbiters but rather reflect the power dynamics and historical contexts in which they were created. For instance, consider the World Bank’s structural adjustment programs in the 1980s and 1990s. These policies, designed to stabilize economies in developing countries, often prioritized fiscal austerity and market liberalization over social welfare. The institutional frameworks imposed by the World Bank mediated political decisions, limiting governments’ ability to invest in public services and exacerbating inequality. This example illustrates how institutions can act as both enablers and constraints, channeling economic outcomes in ways that serve specific interests.

To understand the role of institutions, it’s instructive to examine their dual function: they both reflect and reinforce existing power structures. Take the case of labor laws in advanced economies. In countries like Germany, strong institutional frameworks, such as works councils and collective bargaining, mediate the relationship between employers and employees, fostering cooperation and stability. In contrast, weaker institutional frameworks in countries like the United States often lead to greater income inequality and labor market polarization. The takeaway here is clear: institutions are not merely passive observers of economic and political processes but active participants that shape outcomes. Strengthening or reforming them requires a deliberate focus on their design and implementation.

A persuasive argument for the importance of institutional frameworks lies in their ability to mitigate market failures and political instability. For example, central banks, as key economic institutions, play a critical role in managing inflation and stabilizing financial systems. The Federal Reserve’s response to the 2008 financial crisis, involving unprecedented monetary interventions, demonstrates how institutions can act as shock absorbers during economic turmoil. However, the effectiveness of such institutions depends on their credibility and independence. When political interference undermines these qualities, as seen in some emerging economies, the ability of institutions to mediate outcomes is severely compromised. This highlights the need for robust, transparent, and accountable institutional designs.

Comparing institutional frameworks across different political economies reveals their adaptability and limitations. In Nordic countries, strong welfare institutions have created a balance between market efficiency and social equity, leading to high levels of trust and economic resilience. In contrast, the institutional frameworks of many post-colonial states, often inherited from colonial powers, have struggled to address local needs, perpetuating economic dependency and political instability. This comparative perspective underscores the importance of context-specific institutional design. A one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to succeed; instead, institutions must be tailored to the unique challenges and opportunities of each society.

Finally, a practical guide to analyzing institutional frameworks involves three steps: identify the key institutions governing a particular economic or political process, assess their formal and informal rules, and evaluate their impact on outcomes. For instance, in studying healthcare systems, one might examine the role of regulatory bodies, insurance markets, and public health agencies. By analyzing how these institutions interact and allocate resources, it becomes possible to identify inefficiencies or inequities. The caution here is to avoid reductionism; institutions do not operate in isolation but are embedded in broader social, cultural, and historical contexts. The conclusion is that understanding institutional frameworks is essential for anyone seeking to influence political and economic outcomes, as they are the linchpins that connect policy to practice.

Do Political Ideologies Foster Progress or Divide Societies?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The political economic approach is a framework that examines the interplay between politics and economics, analyzing how political institutions, power structures, and economic systems influence each other. It explores how decisions made by governments, corporations, and other actors shape economic outcomes and vice versa.

Unlike traditional economics, which often focuses on market mechanisms and individual behavior in isolation, the political economic approach incorporates political factors such as state policies, power dynamics, and institutional structures. It emphasizes the role of politics in shaping economic systems and outcomes.

Key areas include the distribution of wealth and power, the role of the state in the economy, globalization and its impacts, labor relations, and the influence of multinational corporations. It also examines issues like inequality, development, and the political consequences of economic policies.