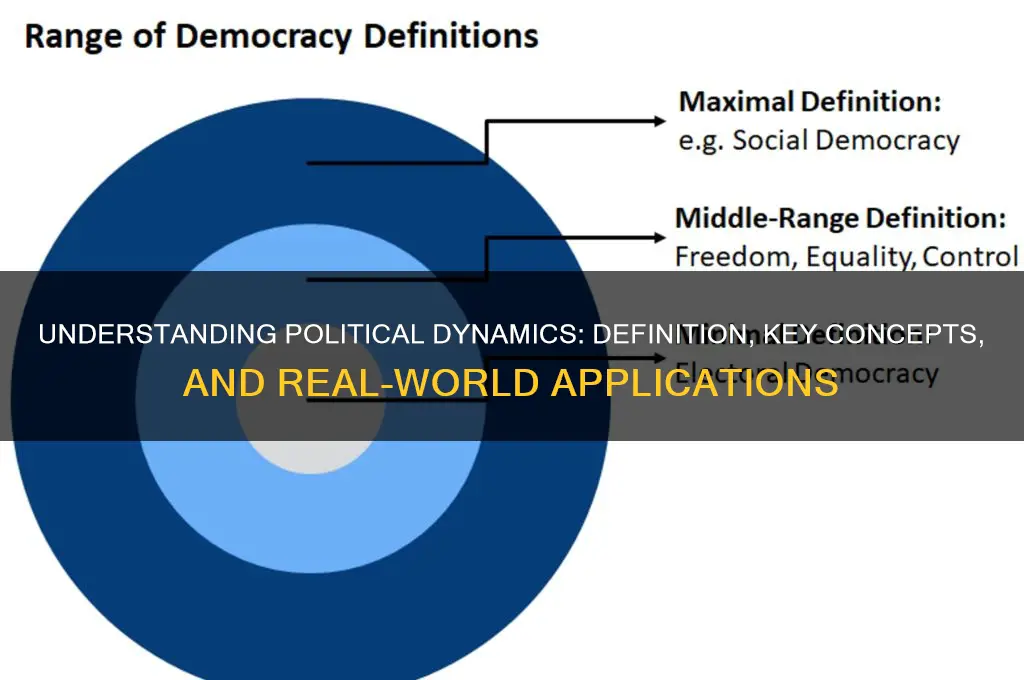

Political dynamics refer to the complex interactions, relationships, and processes that shape political systems, institutions, and behaviors. It encompasses the study of how power is distributed, exercised, and contested within societies, including the roles of governments, political parties, interest groups, and individuals. This field examines the forces driving political change, such as ideology, economic factors, social movements, and international influences, as well as the mechanisms through which decisions are made and policies are implemented. Understanding political dynamics is crucial for analyzing how political systems evolve, respond to challenges, and impact the lives of citizens, offering insights into the functioning of democracy, authoritarianism, and other forms of governance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Power Struggles | Competition for influence, resources, and control among individuals, groups, or institutions. |

| Conflict and Cooperation | Interaction between conflicting interests and collaborative efforts to achieve common goals. |

| Institutional Frameworks | Formal and informal rules, norms, and structures that shape political behavior and outcomes. |

| Ideological Differences | Divergent beliefs, values, and worldviews that drive political agendas and policies. |

| Interest Groups | Organized collectives advocating for specific policies or interests within the political system. |

| Public Opinion | Collective attitudes, beliefs, and sentiments of the populace influencing political decisions. |

| Leadership and Elites | Role of leaders and elite groups in shaping political agendas and mobilizing support. |

| Electoral Processes | Mechanisms for selecting representatives and making political decisions through voting. |

| Policy Formulation and Implementation | Development and execution of government actions to address societal issues. |

| Global and Local Interactions | Influence of international relations, globalization, and local dynamics on political systems. |

| Media and Communication | Role of media in shaping public perception, disseminating information, and influencing political discourse. |

| Social Movements | Collective actions by groups advocating for social, political, or economic change. |

| Economic Factors | Impact of economic conditions, resources, and inequalities on political dynamics. |

| Cultural Influences | Role of cultural norms, traditions, and identities in shaping political behavior and policies. |

| Technological Advancements | Influence of technology on political communication, mobilization, and governance. |

Explore related products

$15.99 $18

What You'll Learn

- Power Structures: Examines how authority is distributed and exercised within political systems

- Conflict & Cooperation: Analyzes interactions between political actors, including alliances and rivalries

- Policy Formation: Explores processes and influences behind creating and implementing political decisions

- Public Opinion: Studies how societal attitudes shape and are shaped by political dynamics

- Institutional Change: Investigates evolution of political organizations and their impact on governance

Power Structures: Examines how authority is distributed and exercised within political systems

Power structures are the invisible scaffolds that shape political systems, determining who holds authority, how decisions are made, and whose interests are prioritized. At their core, they reveal the mechanisms through which power is distributed—whether concentrated in the hands of a few or dispersed across many. For instance, in a presidential system like the United States, power is divided among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, creating a system of checks and balances. In contrast, authoritarian regimes often centralize power in a single leader or party, eliminating countervailing forces. Understanding these structures is critical, as they dictate not only how policies are formed but also how citizens experience governance.

Analyzing power structures requires examining both formal and informal systems. Formal structures are codified in constitutions, laws, and organizational charts, such as the hierarchy of a parliamentary democracy. Informal structures, however, operate through networks, patronage, or cultural norms, often influencing outcomes behind the scenes. For example, in many countries, political dynasties wield significant power despite lacking official positions, illustrating how informal structures can overshadow formal ones. This duality highlights the complexity of power distribution and the need to look beyond surface-level institutions to grasp the true dynamics at play.

To dissect power structures effectively, consider these steps: first, map the formal institutions and their roles, identifying where authority is nominally vested. Second, trace the flow of resources—financial, informational, or social—to uncover who truly wields influence. Third, examine historical and cultural contexts, as they often shape the unwritten rules of power. For instance, in post-colonial states, power structures may still reflect colonial-era divisions, perpetuating inequalities. By combining these approaches, one can reveal the hidden contours of authority and its exercise.

A persuasive argument for studying power structures lies in their direct impact on equity and justice. When power is concentrated in a homogeneous group, marginalized communities are often excluded from decision-making, leading to policies that reinforce inequality. For example, in systems dominated by male elites, gender-sensitive policies are frequently overlooked. Conversely, decentralized power structures, such as those in participatory democracies, can amplify diverse voices and foster inclusivity. Advocating for transparency and accountability in power distribution is thus not just an academic exercise but a moral imperative for building fairer societies.

Finally, a comparative lens reveals how power structures evolve in response to internal and external pressures. The transition from autocracy to democracy in countries like South Africa demonstrates how formal institutions can be reshaped to redistribute power more equitably. Conversely, the rise of populism in some democracies shows how informal structures, such as charismatic leadership and media manipulation, can undermine established systems. These examples underscore the dynamic nature of power structures and the need for ongoing vigilance to ensure they serve the public good rather than private interests.

Is 'No Thank You' Polite? Decoding Etiquette in Modern Communication

You may want to see also

Conflict & Cooperation: Analyzes interactions between political actors, including alliances and rivalries

Political dynamics often hinge on the delicate balance between conflict and cooperation, where alliances and rivalries shape outcomes. Consider the Cold War, a defining example of rivalry where the U.S. and Soviet Union competed ideologically, militarily, and economically without direct conflict. This tension fostered alliances like NATO and the Warsaw Pact, illustrating how rivalries can structure global politics. Such interactions reveal that even in opposition, actors implicitly cooperate by adhering to unspoken rules, such as avoiding nuclear escalation, to maintain stability.

Analyzing these dynamics requires a framework that distinguishes between zero-sum and positive-sum interactions. In zero-sum scenarios, like trade disputes between China and the U.S., one actor’s gain is perceived as the other’s loss, intensifying rivalry. Conversely, positive-sum scenarios, such as climate agreements, allow mutual benefits, fostering cooperation. For instance, the Paris Agreement brought nations together despite differing interests, demonstrating how shared challenges can override rivalries. Understanding this spectrum helps predict when actors will compete or collaborate.

To navigate these interactions, political actors employ strategies like issue linkage, where concessions in one area secure gains in another. For example, during arms control negotiations, the U.S. and Russia linked nuclear reductions to missile defense discussions, balancing rivalry with cooperation. This tactic requires trust and clear communication, highlighting the importance of diplomatic channels. Practitioners should map issues to identify linkage opportunities, ensuring no single dispute derails broader cooperation.

A cautionary note: alliances and rivalries are not static. Shifts in power, leadership, or external shocks can alter dynamics unpredictably. The 2016 Brexit vote strained the UK’s alliances within the EU, while simultaneously fostering new rivalries over trade and sovereignty. Analysts must monitor these shifts, using tools like network analysis to track evolving relationships. For instance, tracking voting patterns in international organizations can reveal emerging blocs or fractures.

In conclusion, conflict and cooperation are not opposites but interdependent forces in political dynamics. By studying their interplay, analysts can decode complex behaviors, from ideological rivalries to pragmatic alliances. Practical steps include categorizing interactions as zero-sum or positive-sum, employing issue linkage, and monitoring relational shifts. This approach equips policymakers and observers alike to anticipate and influence political outcomes in an ever-changing landscape.

Digital Politics: Effective Tool or Overhyped Strategy for Campaigns?

You may want to see also

Policy Formation: Explores processes and influences behind creating and implementing political decisions

Policy formation is the backbone of political dynamics, a complex interplay of interests, ideologies, and institutions that shapes how decisions are made and implemented. At its core, this process involves identifying societal problems, crafting solutions, and translating those solutions into actionable policies. Consider the Affordable Care Act in the United States: its formation required years of debate, coalition-building, and compromise among lawmakers, healthcare providers, and advocacy groups. This example underscores how policy formation is not a linear process but a dynamic, often contentious, journey from idea to implementation.

To understand policy formation, dissect its stages: problem identification, agenda setting, formulation, adoption, implementation, and evaluation. Each stage is influenced by various actors—politicians, bureaucrats, interest groups, and the public—whose priorities and power determine the policy’s trajectory. For instance, during agenda setting, media coverage can elevate an issue, while lobbying efforts can shape its framing. In the case of climate policy, environmental groups push for stricter regulations, while industry representatives advocate for economic feasibility. This tug-of-war illustrates how policy formation is a negotiation of competing interests, not a mere technical exercise.

A critical influence on policy formation is the political environment, which includes electoral cycles, public opinion, and global trends. Policies are often crafted with an eye toward political survival, as seen in pre-election promises or responses to crises. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated policy decisions on lockdowns and vaccine distribution, bypassing typical deliberative processes. This highlights the tension between expediency and thoroughness in policy formation, a balance that policymakers must navigate carefully.

Practical tips for engaging with policy formation include tracking legislative calendars to anticipate key debates, leveraging data to support policy arguments, and building coalitions to amplify influence. For instance, a grassroots campaign might use social media to mobilize public support, while a think tank could publish research to inform policymakers. Understanding these mechanisms empowers individuals and organizations to participate meaningfully in shaping policies that affect their lives.

Ultimately, policy formation is a reflection of political dynamics in action—a process where ideas are tested, alliances are forged, and power is exercised. By examining its stages and influences, one gains insight into why some policies succeed while others fail. This knowledge is not just academic; it is a tool for anyone seeking to impact the decisions that govern society. Whether advocating for change or simply staying informed, grasping policy formation is essential for navigating the complexities of political dynamics.

Is Circle of Dust Political? Exploring the Band's Themes and Message

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Public Opinion: Studies how societal attitudes shape and are shaped by political dynamics

Public opinion is the collective expression of attitudes, beliefs, and values held by a population, and it serves as a powerful force in shaping political dynamics. This interplay is not unidirectional; while societal attitudes influence political decisions, the political environment also molds public sentiment. For instance, during election seasons, public opinion polls become a battleground where candidates gauge their popularity and adjust their campaigns accordingly. A shift in public sentiment towards environmental concerns can propel a candidate to emphasize green policies, demonstrating how public opinion drives political agendas.

Understanding the Feedback Loop

The relationship between public opinion and political dynamics operates in a feedback loop. Political actions, such as policy reforms or legislative decisions, often stem from perceived public demands. Conversely, these actions can reshape public attitudes by either reinforcing existing beliefs or challenging them. For example, the implementation of a universal healthcare system might initially face skepticism, but its success in improving health outcomes could gradually shift public opinion in favor of such policies. This dynamic highlights the importance of studying how political decisions feed back into societal attitudes, creating an ever-evolving cycle.

Practical Implications for Policymakers

Policymakers must navigate this complex interplay to craft effective and sustainable policies. Ignoring public opinion can lead to resistance and policy failure, while overly pandering to it may result in short-sighted decisions. A practical approach involves segmenting public opinion by demographics, such as age groups (e.g., millennials vs. baby boomers) or geographic regions, to tailor policies that resonate with specific audiences. For instance, a policy promoting renewable energy might emphasize job creation for younger voters and energy independence for older ones, demonstrating how nuanced understanding of public opinion can enhance political strategies.

The Role of Media in Amplifying Voices

Media acts as a critical intermediary in the relationship between public opinion and political dynamics. News outlets, social media platforms, and opinion leaders amplify societal attitudes, often shaping the narrative around political issues. However, this amplification can also distort public opinion, as algorithms prioritize sensational content over balanced perspectives. Policymakers and citizens alike must critically evaluate media sources to ensure that public opinion reflects genuine societal attitudes rather than manipulated narratives. For example, fact-checking initiatives and media literacy programs can empower individuals to discern credible information, fostering a more informed public opinion.

Long-Term Impact on Democracy

The study of public opinion and its interaction with political dynamics is essential for the health of democratic systems. When public opinion is accurately represented and addressed, it strengthens civic engagement and trust in institutions. Conversely, systemic disregard for public sentiment can lead to disillusionment and political apathy. For instance, consistent public demand for gun control legislation, if ignored, can erode faith in government responsiveness. By prioritizing the study of public opinion, societies can ensure that political dynamics remain aligned with the needs and aspirations of their citizens, fostering a more inclusive and responsive democracy.

Understanding Political Censorship: Control, Suppression, and Free Speech Limits

You may want to see also

Institutional Change: Investigates evolution of political organizations and their impact on governance

Political organizations are not static entities; they evolve in response to shifting societal demands, technological advancements, and global pressures. Institutional change, therefore, is the lifeblood of governance, ensuring that political systems remain relevant and effective. Consider the transformation of parliaments from exclusive, elite-dominated bodies to more inclusive institutions reflecting diverse societal interests. This evolution didn’t happen overnight—it required deliberate reforms, such as expanding suffrage, introducing proportional representation, and adopting digital tools for public engagement. Each change reshaped the dynamics of decision-making, accountability, and representation.

To understand institutional change, examine its drivers. External factors like economic crises, social movements, or international norms often catalyze reform. For instance, the 2008 financial crisis prompted regulatory overhauls in many countries, strengthening oversight bodies and altering the relationship between governments and financial institutions. Internal factors, such as leadership shifts or bureaucratic inefficiencies, also play a role. Take the example of New Zealand’s public sector reforms in the 1980s, which decentralized decision-making and introduced performance-based management, fundamentally altering how government agencies operated.

However, institutional change is not without risks. Rapid or poorly managed reforms can lead to instability, as seen in post-Soviet states where abrupt transitions to democratic institutions often resulted in weak governance and corruption. A phased approach, combining incremental changes with clear benchmarks, is often more effective. For instance, Estonia’s digital transformation of governance was implemented in stages, starting with e-voting in 2005 and gradually expanding to e-residency and digital IDs, ensuring public trust and technical feasibility at each step.

Practical tips for fostering institutional change include: (1) Conducting thorough stakeholder analyses to identify resistance points and build coalitions. (2) Piloting reforms on a small scale to test feasibility and gather feedback. (3) Leveraging technology to streamline processes and enhance transparency. (4) Embedding evaluation mechanisms to measure impact and adjust course as needed. For example, Rwanda’s post-genocide institutional reforms included regular governance scorecards, which tracked progress in areas like corruption reduction and public service delivery, ensuring accountability and sustained momentum.

Ultimately, institutional change is both a necessity and an art. It requires a delicate balance between innovation and stability, ambition and pragmatism. By studying successful cases—like Singapore’s adaptive governance model or Sweden’s gender-balanced political institutions—policymakers can glean strategies for navigating the complexities of reform. The takeaway? Institutional change is not just about altering structures; it’s about reshaping the very fabric of governance to better serve society’s evolving needs.

Does Political Influence Shape Research Agendas and Outcomes?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political dynamics refers to the interactions, processes, and forces that shape political systems, behaviors, and outcomes. It encompasses how power is distributed, exercised, and contested within societies, institutions, and among individuals.

Political dynamics influence decision-making by determining who has the authority to make decisions, the interests at play, and the strategies used to achieve desired outcomes. Factors like ideology, coalitions, and public opinion play a key role.

Political dynamics are driven by factors such as socioeconomic conditions, cultural values, institutional structures, leadership styles, and external pressures like globalization or geopolitical conflicts.

Understanding political dynamics is crucial for predicting policy outcomes, resolving conflicts, and fostering effective governance. It helps individuals and organizations navigate complex political environments and advocate for their interests.