Political ecology theory is an interdisciplinary framework that examines the relationships between political, economic, and social factors and environmental issues and changes. It critiques the ways in which power dynamics, resource distribution, and global systems shape environmental degradation, access to resources, and sustainability efforts. By integrating insights from geography, anthropology, sociology, and environmental studies, political ecology highlights how ecological problems are often rooted in unequal power structures, historical processes, and capitalist expansion. It emphasizes the importance of understanding the human dimensions of environmental challenges, advocating for justice, and addressing the root causes of ecological crises rather than merely their symptoms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Interdisciplinary Approach | Combines insights from geography, anthropology, sociology, and environmental studies. |

| Power Relations | Focuses on how power dynamics shape access to and control over natural resources. |

| Scale Analysis | Examines environmental issues across local, national, and global scales. |

| Historical Context | Emphasizes the historical roots of environmental conflicts and inequalities. |

| Social Justice | Prioritizes equity and fairness in environmental decision-making and resource distribution. |

| Critique of Capitalism | Challenges capitalist systems that exploit nature and marginalize communities. |

| Community-Based Knowledge | Values local and indigenous knowledge systems in understanding environmental issues. |

| Conflict and Resistance | Highlights struggles and resistance movements against environmental degradation. |

| Political Economy | Analyzes the economic and political structures driving environmental change. |

| Sustainability and Alternatives | Promotes sustainable practices and alternative models of development. |

| Human-Environment Interactions | Explores the complex relationships between societies and their environments. |

| Policy and Governance | Critiques and informs environmental policies and governance structures. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Roots: Origins in environmental movements, Marxism, and critiques of capitalist resource exploitation

- Key Concepts: Power, scale, nature-society relations, and environmental justice as central themes

- Methodologies: Interdisciplinary approaches, case studies, and participatory research in ecological analysis

- Critiques of Capitalism: Examines how capitalism drives ecological degradation and social inequalities

- Global Applications: Studies of resource conflicts, climate change, and indigenous land rights worldwide

Historical Roots: Origins in environmental movements, Marxism, and critiques of capitalist resource exploitation

Political ecology theory emerged as a critical response to the intertwined crises of environmental degradation and social inequality, its roots stretching back to the 1970s and 1980s. During this period, environmental movements gained momentum, drawing attention to the destructive consequences of unchecked industrial development. These movements were not merely about preserving nature; they highlighted how marginalized communities bore the brunt of pollution, deforestation, and resource depletion. This intersection of ecology and justice laid the groundwork for political ecology, framing environmental issues as inherently political and tied to power dynamics.

Marxism provided another foundational pillar for political ecology, offering a lens to analyze how capitalism systematically exploits natural resources for profit. Marxist scholars argued that the drive for accumulation under capitalism leads to the commodification of nature, treating ecosystems as infinite sinks for waste and sources of raw materials. This critique exposed how environmental degradation is not an accidental byproduct of development but a structural outcome of capitalist production. Political ecology inherited this focus on the political economy of resource extraction, emphasizing how global systems of trade and capital shape local ecologies and livelihoods.

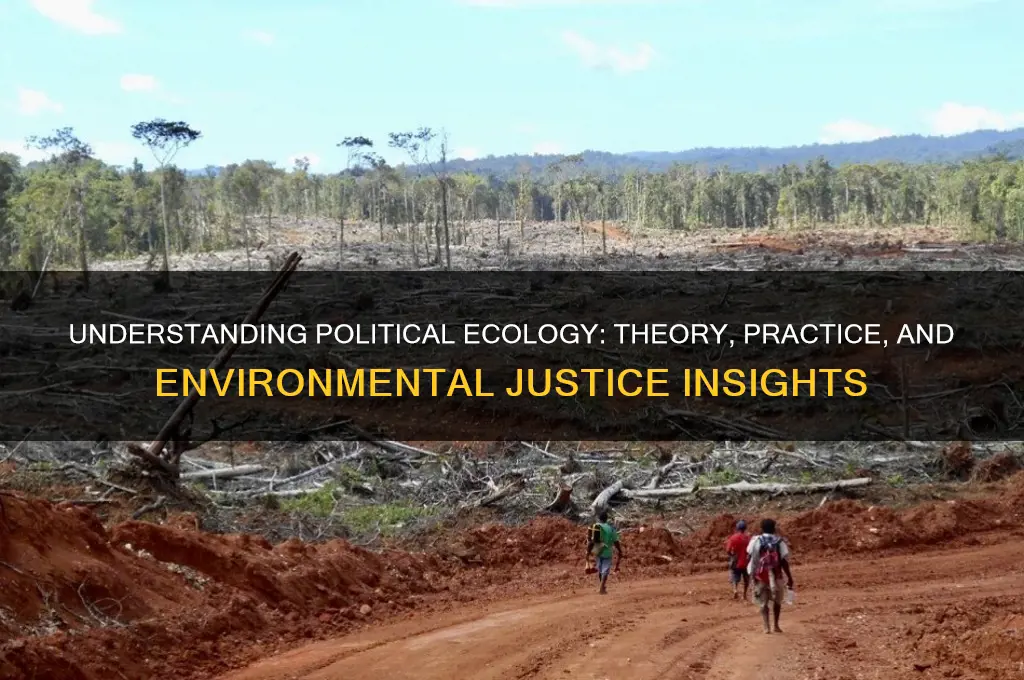

Critiques of capitalist resource exploitation further deepened political ecology’s historical roots. Case studies from the Global South, such as the deforestation of the Amazon or the oil spills in the Niger Delta, illustrated how transnational corporations often operate with impunity, extracting resources while displacing indigenous communities and destroying ecosystems. These examples underscored the need for a theory that connects environmental issues to broader systems of oppression, colonialism, and neoliberal policies. Political ecology emerged as a tool to challenge these injustices, advocating for a more equitable and sustainable relationship between society and nature.

To understand political ecology’s historical roots, consider this practical example: the Chipko movement in India during the 1970s. Villagers, primarily women, hugged trees to prevent loggers from cutting them down, protesting the deforestation that threatened their livelihoods. This act of resistance exemplifies the fusion of environmental activism and social justice, a core tenet of political ecology. It also reflects the influence of Marxist thought, as the movement challenged the state’s prioritization of corporate profits over community well-being. By studying such movements, we see how political ecology evolved from grassroots struggles against capitalist exploitation and environmental destruction.

In conclusion, the historical roots of political ecology are deeply embedded in environmental movements, Marxist analysis, and critiques of capitalist resource exploitation. These origins shaped its core principles: that environmental issues are political, that capitalism drives ecological degradation, and that justice must be central to ecological solutions. By examining these roots, we gain a clearer understanding of why political ecology remains a vital framework for addressing today’s environmental and social challenges. It is not merely an academic theory but a call to action, rooted in decades of struggle and resistance.

Is Government Inherently Political? Exploring the Intersection of Power and Policy

You may want to see also

Key Concepts: Power, scale, nature-society relations, and environmental justice as central themes

Political ecology theory dissects the unequal distribution of power in environmental decision-making, revealing how political and economic forces shape ecological outcomes. Power, in this context, is not merely a tool but a pervasive force that determines who benefits from natural resources and who bears the costs of their exploitation. For instance, consider the global palm oil industry: multinational corporations wield significant power over land use in Southeast Asia, often displacing indigenous communities and destroying biodiverse rainforests. This example illustrates how power dynamics drive environmental degradation and social injustice, making it a central theme in political ecology.

Scale is another critical concept, as it highlights how environmental issues are experienced and addressed differently across local, national, and global levels. A single environmental problem, such as water pollution, manifests uniquely depending on the scale of analysis. At the local level, communities may face immediate health risks from contaminated drinking water, while at the global scale, the same issue contributes to transboundary water conflicts. Political ecology urges us to examine how scale influences both the perception of environmental problems and the effectiveness of solutions. For example, a community-led initiative to clean a river may succeed locally but fail to address upstream industrial pollution without broader policy changes.

Nature-society relations challenge the artificial divide between humans and the environment, emphasizing their interconnectedness. Political ecology rejects the notion of nature as a passive resource, instead viewing it as an active participant in social and political processes. This perspective is evident in the case of the Amazon rainforest, where indigenous communities perceive the forest not as a commodity but as a living entity integral to their culture and survival. By examining these relational dynamics, political ecology reveals how societal values, beliefs, and practices shape—and are shaped by—the natural world.

Environmental justice emerges as the moral and ethical cornerstone of political ecology, demanding fairness in the distribution of environmental benefits and burdens. This concept is particularly evident in the global South, where communities disproportionately suffer from pollution, resource extraction, and climate change impacts despite contributing minimally to these problems. For instance, the Niger Delta exemplifies environmental injustice, as local populations endure oil spills and land degradation while global corporations profit from the region’s resources. Political ecology advocates for transformative solutions that address systemic inequalities, ensuring that environmental policies prioritize the rights and well-being of marginalized communities.

In practice, integrating these key concepts requires a multi-faceted approach. Start by mapping power structures in environmental conflicts to identify who holds authority and who is marginalized. Next, analyze problems across multiple scales to uncover hidden connections and develop comprehensive solutions. Foster dialogue between diverse stakeholders to reframe nature-society relations, recognizing the agency of both humans and ecosystems. Finally, center environmental justice by amplifying the voices of affected communities and advocating for policies that redress historical and ongoing inequities. Together, these steps enable a more equitable and sustainable approach to environmental governance.

Is Corruption Inevitable in Politics? Exploring the Roots and Remedies

You may want to see also

Methodologies: Interdisciplinary approaches, case studies, and participatory research in ecological analysis

Political ecology theory thrives on methodologies that dismantle disciplinary silos, embracing complexity through interdisciplinary approaches, case studies, and participatory research. These methods are not mere tools but philosophical commitments to understanding ecological issues as inherently political, rooted in power dynamics and historical contexts.

Interdisciplinary approaches form the backbone of political ecology, weaving together insights from geography, anthropology, economics, and environmental science. For instance, analyzing deforestation in the Amazon requires integrating ecological data on biodiversity loss with sociological analyses of land tenure systems and economic critiques of global commodity chains. This hybrid lens reveals how environmental degradation is not a natural phenomenon but a consequence of unequal power relations and capitalist expansion. Practitioners must navigate the challenge of integrating disparate methodologies—quantitative models from ecology, qualitative interviews from anthropology, and spatial analysis from GIS—to produce holistic insights.

Case studies serve as the empirical bedrock of political ecology, offering deep dives into specific locales to uncover the intricate interplay of ecology, politics, and economy. A case study of water scarcity in the Indus Basin, for example, might examine how colonial-era irrigation policies, post-independence land reforms, and contemporary climate change intersect to shape water access. Such studies demand meticulous attention to historical context and local knowledge, avoiding the trap of universalizing findings. Researchers should prioritize longitudinal designs, tracking changes over time to capture the dynamic nature of socio-ecological systems.

Participatory research shifts the power dynamics of knowledge production, placing affected communities at the center of ecological analysis. In the Niger Delta, participatory mapping has empowered local communities to document oil pollution and assert land rights against multinational corporations. This approach requires researchers to adopt a facilitative role, ensuring participants co-define research questions, collect data, and interpret findings. Practical tips include using accessible tools like GPS devices and visual aids, ensuring language barriers are addressed, and establishing clear protocols for data ownership and dissemination.

These methodologies are not without challenges. Interdisciplinary work risks superficial integration, case studies can struggle with generalizability, and participatory research may face logistical and ethical hurdles. Yet, when combined thoughtfully, they offer a robust framework for uncovering the political dimensions of ecological crises. By embracing these approaches, political ecologists can produce actionable knowledge that not only explains but also challenges the status quo, fostering more just and sustainable futures.

Could You" vs. "Can You": Mastering Polite English Phrase

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Critiques of Capitalism: Examines how capitalism drives ecological degradation and social inequalities

Capitalism, with its relentless pursuit of profit and growth, has become a central target of critique within political ecology. This economic system, characterized by private ownership and market-driven production, is argued to be inherently incompatible with ecological sustainability and social equity. The critique lies in the very foundations of capitalism, where the extraction of natural resources and the exploitation of labor are not merely side effects but essential mechanisms for its functioning.

The Ecological Cost of Capitalist Expansion:

Imagine a forest, rich in biodiversity, being cleared to make way for a monoculture plantation. This scenario illustrates a common pattern where capitalism's insatiable appetite for resources leads to environmental degradation. Political ecologists argue that the capitalist drive for endless accumulation encourages the overexploitation of ecosystems, treating nature as a mere input for production. For instance, the Amazon rainforest, often referred to as the "lungs of the Earth," has been subjected to rampant deforestation for cattle ranching and soybean cultivation, primarily driven by global market demands. This not only results in habitat loss and species extinction but also contributes to climate change, as forests act as crucial carbon sinks. The critique here is that capitalism's short-term profit motives undermine the long-term health of ecosystems, leading to irreversible damage.

Social Inequalities and the Capitalist Structure:

Beyond environmental concerns, political ecology also highlights how capitalism exacerbates social inequalities. The system's inherent logic of competition and accumulation tends to concentrate wealth and power in the hands of a few, while marginalizing the many. Consider the global garment industry, where fast fashion brands thrive on cheap labor and exploitative practices. Workers, often in developing countries, face poor working conditions, low wages, and limited rights, all to maximize profits for corporations. This dynamic is not an anomaly but a structural feature of capitalism, where the pursuit of profit can lead to the systematic disenfranchisement of certain communities. The critique extends to the global scale, where capitalist expansion has historically been intertwined with colonialism and neocolonialism, creating and maintaining power imbalances between nations.

A Call for Systemic Change:

Addressing these issues requires more than superficial reforms; it demands a fundamental rethinking of our economic systems. Political ecology scholars advocate for a transformative approach, challenging the dominance of capitalism and proposing alternative models. This could involve exploring degrowth strategies, which prioritize well-being and sustainability over GDP growth, or promoting cooperative and communal ownership structures that democratize economic decision-making. For instance, community-led initiatives like cooperative farms or worker-owned businesses can foster more equitable and environmentally conscious practices. By decentralizing power and prioritizing local needs, these alternatives offer a path towards mitigating both ecological degradation and social inequalities.

In essence, the critique of capitalism within political ecology is a call to recognize the deep-rooted connections between economic systems, environmental health, and social justice. It urges us to question the status quo and explore radical yet necessary changes to create a more sustainable and equitable world. This perspective encourages a holistic understanding of the interconnected crises we face and provides a framework for imagining and building alternative futures.

Modernist Poetry and Political Themes: An Exploration of Their Intersection

You may want to see also

Global Applications: Studies of resource conflicts, climate change, and indigenous land rights worldwide

Resource conflicts are not merely disputes over land or commodities; they are deeply rooted in power dynamics, historical injustices, and global economic systems. Political ecology examines how these conflicts arise from unequal access to resources, often exacerbated by neoliberal policies and corporate interests. For instance, in the Niger Delta, oil extraction has led to environmental degradation, displacement of communities, and violent clashes between locals and multinational corporations. Here, the theory highlights how resource exploitation is intertwined with colonial legacies and contemporary capitalism, revealing that such conflicts are not isolated incidents but symptoms of broader structural inequalities. Understanding this requires tracing the global supply chains and financial flows that sustain these extractive industries, making it clear that local struggles are inherently global in nature.

Climate change, often framed as a universal challenge, disproportionately affects marginalized communities, particularly indigenous peoples and those in the Global South. Political ecology critiques the technocratic solutions—such as carbon markets or large-scale renewable energy projects—that often sideline the voices of those most impacted. For example, the construction of hydroelectric dams in the Amazon, while marketed as "green energy," has flooded indigenous territories and disrupted ecosystems. This approach underscores the importance of climate justice, which demands not only reducing emissions but also addressing the historical responsibilities of industrialized nations and ensuring equitable adaptation measures. By centering the knowledge and rights of indigenous communities, political ecology offers a more inclusive and sustainable pathway to addressing the climate crisis.

Indigenous land rights are a cornerstone of political ecology, as these communities often serve as stewards of biodiversity and guardians of traditional ecological knowledge. However, their lands are increasingly threatened by agribusiness, mining, and conservation projects that prioritize profit over people. In Brazil, the deforestation of the Amazon is directly linked to the weakening of indigenous land protections under political regimes favoring agribusiness. Political ecology emphasizes the need to recognize indigenous sovereignty not just as a human rights issue but as a critical strategy for environmental conservation. Studies show that indigenous-managed lands have lower deforestation rates and higher biodiversity compared to protected areas managed by governments. This evidence challenges the notion that conservation requires excluding human presence, advocating instead for models that integrate indigenous knowledge and practices.

To apply political ecology globally, researchers and activists must adopt a multi-scalar approach, connecting local struggles to global processes. For instance, a study on palm oil expansion in Indonesia would analyze not only the deforestation and displacement of communities but also the global demand for cheap vegetable oil in processed foods. This perspective encourages solidarity across movements, such as linking indigenous land defenders in Canada with anti-extractivist activists in Ecuador. Practical steps include mapping resource flows, documenting human rights violations, and amplifying grassroots voices in international forums. By doing so, political ecology transforms abstract concepts like "sustainability" into actionable strategies that challenge the root causes of environmental and social injustices. Its global applications remind us that the fight for a just and sustainable world is inherently political, requiring both critical analysis and collective action.

Corporations: Economic Powerhouses or Political Influencers? Exploring Their Dual Role

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political ecology theory is an interdisciplinary approach that examines the relationships between political, economic, and social factors and environmental issues. It explores how power dynamics, resource distribution, and human activities shape environmental outcomes, often focusing on the unequal impacts of environmental change on marginalized communities.

Traditional ecology primarily focuses on the scientific study of ecosystems and biological interactions, whereas political ecology integrates social, political, and economic dimensions to understand environmental problems. It emphasizes the role of human institutions, policies, and power structures in shaping environmental degradation and conservation efforts.

Key themes in political ecology include the commodification of nature, environmental justice, the role of global capitalism in resource extraction, and the impacts of development projects on local communities. It also highlights the importance of grassroots movements and alternative approaches to sustainability.