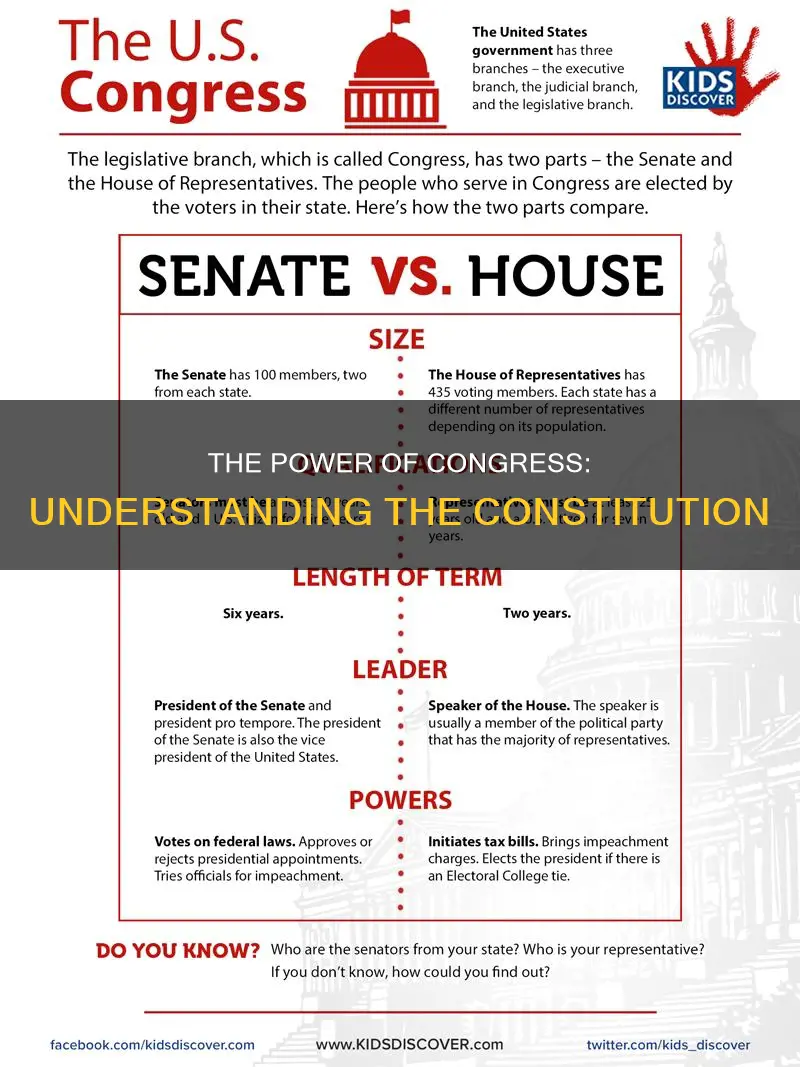

The United States Constitution grants Congress several powers, including the ability to declare war, raise and maintain armed forces, and make rules for the military. Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution outlines eighteen enumerated powers, including the power to tax and spend for the general welfare and common defence, borrow money, regulate commerce with states, other nations, and Native American tribes, and establish citizenship naturalization laws. Congress also has the authority to impeach a sitting President, with the Senate being responsible for the impeachment trial. The Necessary and Proper Clause grants Congress the ability to create laws necessary to carry out its powers, and constitutional amendments have further expanded congressional powers, such as the power to enforce voting rights and the right of citizens aged eighteen or older to vote.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Legislative powers | All legislative powers are vested in a Congress of the United States, which consists of a Senate and House of Representatives. |

| Election of Senators and Representatives | The election of Senators and Representatives is decided by the legislature of each state, but Congress may at any time make or alter regulations, except as to the places of choosing Senators. |

| Powers related to war and the military | Congress has the power to declare war, raise and maintain the armed forces, and make rules for the military. |

| Power to tax and spend | Congress has the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States. |

| Power to borrow money | Congress has the power to borrow money. |

| Regulation of commerce | Congress can regulate commerce with states, other nations, and Native American tribes. |

| Establishing laws | Congress can establish citizenship naturalization laws, bankruptcy laws, and laws that are necessary and proper to carry out the laws of the land (Necessary and Proper Clause). |

| Impeachment | The House of Representatives has the sole power of impeachment, and the Senate has the sole power to try all impeachments. |

| Power to choose the president or vice president | If no one receives a majority of Electoral College votes, the Twelfth Amendment gives Congress the power to choose the president or vice president. |

| Authority to enact legislation | The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments gave Congress the authority to enact legislation to enforce the rights of all citizens regardless of race, including voting rights, due process, and equal protection under the law. |

| Power of taxation | The Sixteenth Amendment extended the power of taxation to include income taxes. |

| Power to enforce voting rights | The Nineteenth, Twenty-fourth, and Twenty-sixth Amendments gave Congress the power to enforce the right of citizens, who are eighteen years or older, to vote regardless of sex, age, and whether they have paid taxes. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

The power to tax and spend

The US Constitution grants Congress the power to tax and spend. This power is outlined in Article I, Section 8, Clause 1, also known as the Spending Clause, which states that Congress has the authority to "lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises" to fund the government and provide for the "common Defence and general Welfare" of the United States.

This power to tax and spend is one of Congress's most important powers, as it enables the federal government to raise revenue and fund its operations. The taxes collected by Congress are used to pay off debts, support the military, and promote the general welfare of the country.

The Supreme Court has historically interpreted this power broadly, stating that it "reaches every subject" and "embraces every conceivable power of taxation." This interpretation has allowed Congress to pursue a wide range of policy objectives and attach conditions to federal funding allocations. For example, Congress has used its spending power to implement federal programs such as Social Security, Medicaid, and federal education initiatives.

However, there are some limitations on Congress's power to tax and spend. The Constitution requires that all "Duties, Imposts, and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States." Additionally, the Supreme Court has ruled that Congress cannot use its taxing power to interfere with certain state functions or to coerce states into accepting funding conditions. Furthermore, any conditions attached to federal funds must be unambiguous, pursue the general welfare, relate to a federal interest, and not induce unconstitutional conduct.

Congress's power to tax and spend is a critical tool for the federal government to raise revenue, implement policies, and provide for the general welfare of the United States, subject to constitutional and judicial constraints.

Drinking Age: Is It in the Constitution?

You may want to see also

The power to declare war

The US Constitution, in Article I, Section 8, Clause 11, gives Congress the power to declare war. This is often referred to as the War Powers Clause. The exact wording is: " [The Congress shall have Power ...] To declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water".

The Declare War Clause unquestionably gives Congress the power to initiate hostilities. However, the extent to which this limits the President's ability to use military force without Congress's approval is highly contested. While most agree that the President cannot declare war on their own authority, some argue that they can initiate the use of force without a formal declaration.

There is also debate about the form of the declaration. The Constitution does not specify, and modern hostilities typically do not begin with a formal declaration. For example, the Vietnam War is considered an "undeclared war" as no official statement was issued. However, it is generally accepted that Congress has the exclusive power to declare war, and there have been five wars declared under this power: the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, and World War II.

Congress has also provided other authorizations to use force, such as when approving the use of force to protect US interests and allies in Southeast Asia, which led to the Vietnam War. There is debate about the appropriateness of these authorizations and the role of the executive branch in pushing for them. In 1973, Congress passed the War Powers Resolution, requiring the President to obtain a declaration of war or a resolution authorizing the use of force.

John Marshall's Constitution: A Personal Interpretation

You may want to see also

The power to raise and maintain armed forces

The Constitution of the United States grants Congress the power to raise and maintain armed forces. This power is derived from Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, which outlines the enumerated powers of Congress.

The framers of the Constitution intentionally gave Congress the authority to raise and support armies, separate from its power to call on militias, to act as a check on the president's commander-in-chief powers. This was done to prevent the president from having excessive control over the military.

Congress's power to raise and maintain armed forces includes the ability to classify, conscript, and regulate manpower for military service. It also entails the responsibility to fund the armed forces. However, there is a limitation that "no appropriation of money to that use shall be for a longer term than two years." This limitation was included to address the fear of standing armies.

Throughout history, there have been conflicts between Congress's power to raise and maintain armed forces and the president's war powers. For example, the Selective Service Act of 1917, which expanded the military through conscription, was challenged on the grounds that it violated states' rights to maintain a well-regulated militia. The Supreme Court, however, upheld the Act's constitutionality, asserting that Congress's power to raise armies took precedence over states' rights to maintain militias.

Sex Offender Tier Level Reduction: What Factors Constitute Change?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The power to regulate commerce

The Commerce Clause, outlined in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the US Constitution, grants Congress the power to "regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes". This clause has been pivotal in shaping the balance of power between the federal government and the states, and has been interpreted and reinterpreted by the Supreme Court over the years, with ongoing debates about its scope.

The Commerce Clause gives Congress the ability to regulate the economy and protect the interests of the American people. This includes the regulation of trade activities beyond state borders, encompassing a wide array of economic transactions. Initially, the Supreme Court interpreted this power narrowly, focusing on the direct movement of goods across state lines. However, as the economy evolved, the Court recognised the clause's broader authority, and began to interpret it more expansively.

The Commerce Clause has been used by Congress to justify exercising legislative power over state activities and their citizens, leading to significant controversy. The lack of a precise definition of "commerce" in the Constitution has fuelled debates about the extent of Congress's powers. Some argue that it refers solely to trade or exchange, while others contend that it encompasses a broader scope of commercial and social intercourse between citizens of different states.

The interpretation of the Commerce Clause has evolved over time, with landmark Supreme Court cases shaping its scope. In Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), the Court affirmed federal supremacy in regulating interstate commerce, setting a precedent for a broad interpretation of the clause. This interpretation was further expanded in the New Deal era, with cases like NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp (1937) and Wickard v. Filburn (1942), which recognised the cumulative effect of intrastate activities on interstate commerce.

However, in United States v. Lopez (1995), the Supreme Court attempted to curtail Congress's broad powers under the Commerce Clause, returning to a more conservative interpretation. This decision was reflected in later cases such as United States v. Morrison (2000) and National Federation of Business v. Sebelius, which held that certain laws, such as those regarding gun possession and the individual mandate to buy health insurance, were beyond Congress's authority to regulate commerce.

Christian Morality vs. Constitution: A Comparison

You may want to see also

The power to impeach

The US Constitution, in Article II, Section 4, outlines that the President, Vice President, and all Civil Officers of the United States shall be removed from office upon impeachment for and conviction of "Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors." The Constitution limits the grounds for impeachment to these specific categories but does not define "high crimes and misdemeanors." This phrase refers to offences against the government or the constitution, grave abuses of power, violations of the public trust, or other political crimes.

Impeachment is a serious process that has been invoked occasionally throughout US history. It serves as a check on the executive branch and holds public officials accountable for their actions. The power to impeach is an important tool for Congress to uphold the integrity of public office and ensure that officials act in the best interests of the nation.

Who Counts as a Household Member for Poverty Line Calculations?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

One power of Congress listed in the US Constitution is the power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and excises.

Another power of Congress listed in the US Constitution is the power to declare war.

The Necessary and Proper Clause permits Congress to "make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the United States, or in any department or officer thereof." This clause has been interpreted broadly, widening the scope of Congress's legislative authority.

Congress has the power "to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries."